If you have ever listened to classic pop, you’ve certainly heard Louie Shelton’s guitar work. That’s Shelton purveying the signature guitar part and solo on “Last Train to Clarksville” by the Monkees, the soaring instrumental hook and solo on Boz Scaggs’ “Lowdown,” the solo on Lionel Ritchie’s megahit “Hello,” and the silky licks on “Diamond Girl” by Seals and Crofts. You might also have come across his playing on records by John Lennon, Whitney Houston, Barbra Streisand, Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross, the Carpenters, Joe Cocker, Kenny Rogers, the Mamas & the Papas, James Brown, Ella Fitzgerald, and many others.

Yet, despite a decade rife with movies about the musicians who labor behind the scenes to create the recordings and live shows we love—The Wrecking Crew, Sidemen, Hired Gun, Muscle Shoals, 20 Feet from Stardom—you could be forgiven for not knowing his name as he is largely absent from these historical films.

Why the limited visibility? Perhaps because Shelton’s tenure as an A-team session man came on a cusp, as the old guard, jazz-based guitarists handed off the mantle to younger, rock-influenced players. Shelton arrived in Los Angeles just as some Wrecking Crew guitarists like Vinnie Bell, Al Casey, Howard Roberts, and Tommy Tedesco were retiring, while others—James Burton, Glen Campbell, Barney Kessel—were switching career paths. He appeared right at the onset of the new wave of players, which included Larry Carlton, Jay Graydon, and eventually Steve Lukather and Michael Landau. Shelton quickly became a first-call player, and almost as quickly left day to day session work to be a producer of megahits. It also doesn’t help his profile that he has spent much of the last four decades in Australia.

Name recognition aside, Shelton played an essential part in the transition of the Los Angeles guitar sound from the “rock ’n’ roll” twang of the ’50s and early ’60s to the fatter “rock” tones of the late ’60s and ’70s. His incredible story is one of immense talent and extraordinary luck combining to create a career that is legendary among those fortunate enough to be aware of it.

Shelton was born in 1941, in Little Rock, Arkansas. Neither of his parents played an instrument, but they and his sisters were avid music fans, always listening to the radio or playing records. From age 3, Shelton was imitating a guitar with a broom or stick. This caught the eye of one sister, who bought him a $13 Stella guitar for his 9th birthday, later buying him a Harmony f-hole acoustic, and ultimately a Supro electric. “It had a neck like a baseball bat,” he recalls.

Winning second place at a talent contest earned him a spot on a radio show where he met Shelby Cooper and the Dixie Mountaineers. Cooper recognized his prodigious talent and soon asked him to join the old-timey country band.

“By the time I was 12, I was playing five days a week,” says Shelton. “I lived with Shelby and his wife, Sarah Jane, for two years, through the sixth and seventh grade. It formed my direction. By the end I was a working musician.”

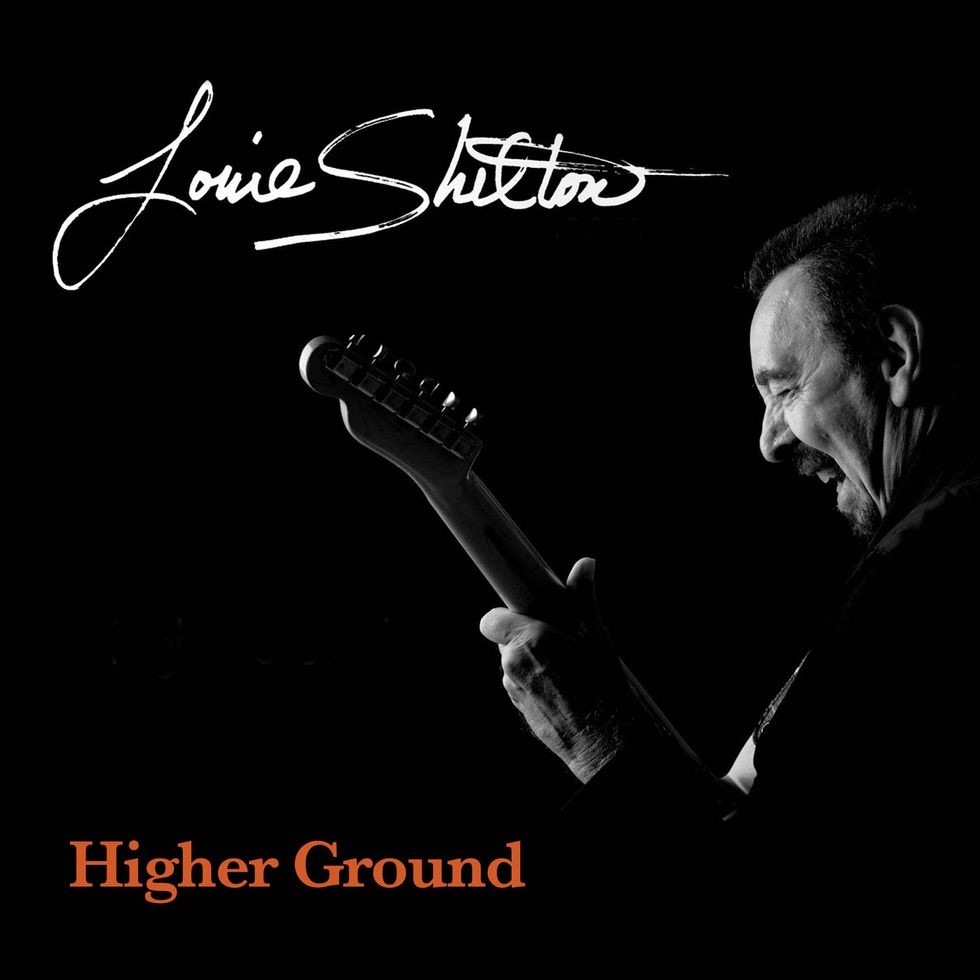

TIDBIT: Shelton’s latest solo album, Higher Ground, contains nine instrumental arrangements of Stevie Wonder tunes. “I’ve been playing Stevie’s stuff for years,” says Shelton, “ever since he put out ‘Uptight.’ You realize how good ‘Too High’ is when you try to do a chord chart for it—it’s all over the place.”

The Cooper family home had a room with a tape recorder, where, during the school semester, Shelton would help prerecord their radio show after classes. He also played on Little Rock’s Saturday night Barnyard Frolic radio broadcast, where he backed up many of the solo artists. With the advent of television, the band was given a live TV show every Wednesday night. There, the tween now known as Little Junior Shelton was featured playing Chet Atkins and Jimmy Bryant songs he learned from records given to him by Cooper.

“I only play by ear,” says Shelton. “I never had any formal training. I had a friend down the street who showed me basic E and D chords. I was also picking some stuff up off the radio. Everything came easy for me on the guitar.”

When the Supro could no longer cut it for the newly minted professional, Cooper bought him a new 1952 Fender Telecaster and Fender amp.

The guitarist returned to Little Rock for holidays and summers. “The summer I went back in ’55, I started playing in some clubs in Little Rock,” says Shelton. “I was always the youngest guy in the country bands. I also started playing in a club where we played rock and roll.” Shelton was still playing the Telecaster in the Little Rock clubs, but after seeing Chuck Berry play a blonde Gibson ES-350, he traded the Tele for a 350.

When Cooper and his wife divorced, Shelton stayed in Little Rock playing clubs. It was there, at age 16, that he met future session legend Reggie Young. “Reggie asked me, ‘Have you ever heard of Barney Kessel or Johnny Smith?’ I hadn’t, so I got their records and wore them out. I was keen to learn those unbelievable chords and phrases. It rounded me as a player so that by the time I got to L.A. it didn’t matter what they threw at me.”

In Little Rock, Shelton and a steel player would play music inspired by Speedy West and Jimmy Bryant. “We took a six-night-a-week gig in Santa Fe,” he says, “and we both bought the new tweed Fender 4x10 Bassmans.” While working around nearby Albuquerque, he met a young guitarist named Glen Campbell. “We played together for a couple of years before he went out to L.A.,” says Shelton. Back in Santa Fe, the guitarist formed a band that would back up artists like Bobby Vee and Johnny Burnett when they came through the area. “Everybody said, ‘You guys need to go to California. You’d do great out there.’”

Shelton ultimately moved to Los Angeles in 1963, and Campbell was the only person he knew there. “Glen put us up for a few days until we got a place,” he recalls. “He took me to a Ricky Nelson session, where I met James Burton and Joe Osborne. He would call me to sub for him if he booked a late session and needed someone to fill in for him the next day on an early morning one.”

In those days, Shelton’s lack of reading ability was rarely an issue. “I was afraid someone would put notes in front of me, but it never happened,” he says. “I could read a chord chart, and most of the stuff was simple. If you can play ‘Moonlight in Vermont’ you have no trouble playing the three-chord stuff. If it was my first call from someone, I’d tell them if they needed a reader they should call Barney Kessel or somebody like that. They’d say, ‘Oh no, we just want to hear your licks’.”

With players like Shelton, James Burton, and Glen Campbell, producers didn’t write out detailed charts. Instead, they preferred to hear the parts the guitarists invented. “I had a good sense of time and didn’t miss a lot of notes,” says Shelton. “When I got the opportunity to do sessions, it always went well for me.”

One reason for this was Shelton’s familiarity with, and love of, a wide range of music. “I could figure out what kind of song it was and zero in on what would work. I would think, ‘What would George Harrison or Stephen Stills from Buffalo Springfield play on this?’ If it was Barbra Streisand, I knew I had to play some classy stuff, so I would be thinking of Johnny Smith or someone like that. I’m still that way. I’m on YouTube every night checking out great new guitar players.”

Though studio work was going well, Shelton was not yet high enough up the pecking order to do it full time. While getting established, Shelton toured and played the local clubs for two years with various bands. “I got this gig with the folk duo Joe and Eddie. They had a record deal and were doing all the big universities and major TV shows. When that gig fell apart, I played in a band in Hollywood.”

Tennessee luthier Mark Lacey built Shelton’s signature model archtop. It features a spruce top, quilted maple back and sides, and a Johnny Smith-style Seymour Duncan floating pickup. Photo courtesy of Louie Shelton

It was in Hollywood that Shelton would reconnect with Jim Seals and Dash Crofts. Before they were “Seals and Crofts,” the two musicians had played sax and drums respectively in the touring version of the Champs, who had a hit with the instrumental “Tequila.” Shelton had first met them when that band came through Santa Fe, with Glen Campbell on guitar. After quitting the Champs, Seals and Crofts put together a band called the Mushrooms.

“Their guitar player quit and I joined them to play the clubs around L.A.,” says Shelton. Crofts was dating a woman whose mother was a manager with connections in Las Vegas. She began booking them gigs at legendary Vegas venues like the Stardust, the Flamingo, and the Sahara. Producer Richard Perry came to see the band and signed them to Warner Bros. as the Dawnbreakers. Though that band didn’t succeed, Perry began calling Shelton to do sessions. Through him, the guitarist would go on to play on records by Tiny Tim, Ringo Starr, and Streisand.

Electric Guitars

Mark Lacey Custom Louie Shelton archtop with Seymour Duncan floating pickup

Early-’70s Fender Stratocaster with Seymour Duncan ’59 bridge humbucker, Floyd Rose, and custom neck made by Aussie luthier Greg Fryer

Gibson ES-175

Gibson ES-339

Gibson ES-355

Fender Vintage ’52 Telecaster reissue with Fender noiseless pickups

Fender Telecaster with EMG pickups

1941 Epiphone lap steel

Acoustic Guitars

1951 Martin D-18

Ayers CSR parlor

Cigano Selmer-style

Aria classical

Regal resonator

Amps

Fender Tweed Deluxe

Fender Bassman head

Fender Blues Junior

Fender Princeton

Mesa/Boogie Mark II

Effects

Line 6 Pod Plus

ADA rackmount preamp

Roland GP-10

Ibanez TS-10 Tube Screamer

Pro Co RAT

Xotic SP Compressor

Xotic AC Booster

Hermida Zendrive

Vertex Ultraphonix Overdrive

Voodoo Labs Micro Vibe

TC Flashback

TC Hall of Fame

TC Polytune

Electro Harmonix Lester G

Electro Harmonix Memory Man

Electro Harmonix Pulsar

Electro Harmonix B9

Arion Stereo Chorus

Boss DD-2 delay

MXR Dyna Comp

Carl Martin Greg Howe’s Lick Box

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010-.046)

Custom medium picks

Perry also introduced Shelton to up-and-coming songwriters Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart. The guitarist began doing their demos, and when they were hired to create music for the Monkees’ TV show, they called him. “I was working in Las Vegas when they got that deal,” he says. “They talked me into coming back to L.A. because they wanted me on that session. When ‘Last Train to Clarksville’ hit, everybody started calling me and I knew it was my chance. I had to stay in L.A. at that point. If they call and you’re not there, they just go on to the next guy.”

Shelton entered the scene at a critical moment. Barney Kessel had already left. Tommy Tedesco, Joe Pass, Dennis Budimir, and Howard Roberts were still there, but it was the end of their run. “I was the newest and youngest member of that group,” says Shelton. “Once people like myself and Larry Carlton showed up, they quit calling those guys, who all came from bebop backgrounds and didn’t play rock ’n’ roll very well. The best they could do was a bad imitation of surf music. Whereas, guys like me and Larry, and, later on, Lee Ritenour and Steve Lukather, had listened to the Beatles and Led Zeppelin. The older guys would say, ‘I hate this stuff. I can’t wait to get out of here.’ And rightfully so. They should have been playing as artists. But there wasn’t any work for them in those days because jazz had taken a nosedive. Even Joe Sample and Wilton Felder from the Jazz Crusaders ended up doing Motown sessions with me.”

Shelton did plenty of guitar work for Motown in Los Angeles, appearing on records by the Jackson 5 and Marvin Gaye. On the Jackson’s “I Want You Back,” Shelton is playing “telegraph” octaves throughout the whole song. “David T. Walker was doing the sliding things, along with Don Peake doubling the bass line,” says Shelton. “On ‘ABC,’ I did the fuzz guitar. In those days, we didn’t have pedalboards, but I had the MXR Distortion+. I plugged the guitar into that and out into a direct box. On Motown sessions, they would let us rehearse through amps, but when we recorded we had to plug into direct boxes.” It is going direct that likely made the Distortion+ sound more fuzz-like.

For the Jackson 5 tunes, Shelton usually played a Fender Telecaster or Stratocaster, while his amp of choice during his session heyday was a Fender Princeton with a Paul Rivera mod (though not done by Rivera himself). “You weren’t allowed to play loud in the studios because there were so many open mics on the drums and pianos,” says Shelton. “There was no need to carry some big amp around, so I got the Princeton. The Rivera mod gave me a master volume so I could get some distortion without having it too loud.” He also used a Strat for his warm-sounding, iconic solo on Lionel Ritchie’s “Hello.” “I always got a good jazz tone out of Fenders,” he says.

By the time Shelton recorded the “Hello” solo, he had long left behind the three-session-a-day grind of studio work in favor of producing—beginning with his old friends and bandmates Seals and Crofts. “After Summer Breeze became a hit in 1972, I stopped taking so many sessions,” he explains. “I tried to keep going, but felt my own productions were suffering because I didn’t have enough time to put into them.” But Shelton continued to play guitar on Seals and Crofts sessions, and his silky licks and solo on “Diamond Girl,” played on a Gibson ES-335, leapt out of the radio in 1973.

Shelton didn’t completely abandon sessions. “I’d take a few, if it was people I knew,” he says. “If Lionel Richie called, I’d do that. When David Paich did the Boz Scaggs album Silk Degrees, I thought, ‘That’ll be fun.’” For his iconic solo on Scaggs’ “Lowdown,” Shelton wielded a Gibson L-5S solidbody. “I had one pedal,” he says. “It might have been the Distortion+. I had a clean sound for rhythm, and for the solo I clicked on the pedal. I was going through the little Princeton amp on that one.”

In 1984, at the height of his success as a producer and session player, Shelton moved to Australia. “We wanted to give our kids a cleaner environment for a while,” he says. “I was producing a band from Sydney in L.A. They kept saying, ‘You would love Australia.’ We went there and fell in love with the place.”

Shelton only planned to stay in Australia for five years, but ended up staying 12. His brother-in-law, and former Dawnbreakers bandmate, engineer Joe Bogan, took the studio they shared from L.A. to Nashville, so when Shelton moved back to the States, he landed in Music City. While in Nashville, he produced a record called Nashville Guitars, featuring star pickers Reggie Young, Johnny Hiland, Jimmy Olander, Ray Flacke, and others. “Doing sessions in Nashville, I’d be sitting alongside these fantastic guitar players and thought it’d be nice if people could hear them,” he says. “I didn’t get Brent Mason because he had just done his solo album.”

Over the last six decades, Shelton has also released six albums of his own. On Bluesland, he reveals a deep knowledge of and respect for the genre. “I used to hear this stuff on African-American radio when I was very young,” he recalls. “I remember hearing ‘My Babe’ on the jukebox in some of the Little Rock restaurants. I found my first B.B. King record in ’58 for 99 cents in a grocery store. It had a song, ‘You’re on the Top.’ Boz Scaggs sings it on the first track of Bluesland.”

Shelton’s tone on the record is more classic L.A. studio than vintage South Side Chicago. “I was going back and forth between my Tele and my small-bodied Gibson 339, through mostly just my Princeton amp. It’s such an organic sound. All of those blues players were crushing it through only an amp. I might put a bit of Tube Screamer on there, but I can get as much dirt as I want with just my amp.” With either guitar, Shelton usually uses the bridge pickup, rolling a little top end off with the tone control. “You’ve got to find a sweet spot,” he says.

Shelton’s latest record, Higher Ground, is a collection of Stevie Wonder tunes, conceived as a concept album that would appeal to smooth jazz radio. “I’ve been playing Stevie’s stuff for years, ever since he put out ‘Uptight.’ You realize how good ‘Too High’ is when you try to do a chord chart for it—it’s all over the place.” The guitar on “Higher Ground” and “Boogie on Reggae Woman” sounds like a continuation of Shelton’s bridge-driven Bluesland tone. “That’s a ’52 reissue Tele. When I was in Nashville, I went to the Fender rep and told him I was looking for something as close as possible to my old ’52. I played about 10 Teles and picked the one that felt and sounded most like that. It’s now my favorite guitar. I take it on the road with me.”

After a decade in Nashville, Shelton decided to join two of his children who had moved back to Australia to raise their own offspring. Now he lives in the Gold Coast, a city south of Brisbane, still touring and recording from there. “I do a lot of cruise ship performances as a special guest, backed by the ship’s band,” he says. He’ll do a 45-minute medley of the hits he played on, as well as other guitar-based music by ZZ Top, Santana, and Les Paul. When gigging around Australia, he might play a jazz club, or a four-set club gig, where he will employ a vocalist and perform everything from Fleetwood Mac to Stevie Wonder tunes. “In the clubs, people like stuff they’re familiar with,” he explains. “They’re not interested in hearing original material, unless it’s a jazz gig or a Louie Shelton gig. Then they’ll pretty much listen to whatever I play.”

Just as his choice of material varies with the gig, Shelton’s choice of pick depends on the situation. “I usually use medium picks with my name on it, because I throw a couple to the audience,” he says. “I’ve got every shape. Sometimes I’ll grab a mandolin-style pick like Johnny Smith and Jimmy Bryant used. I use thumbpicks if I’m playing fingerstyle, like Chet Atkins. I use three false nails because plucking steel strings will cut my own up in no time.”

For his live gigs, Shelton favors a Fender Blues Junior. With a bigger band or in a larger venue, he might employ a 1x12 Fender Hot Rod Deluxe. The original modified Princeton has been relegated to the studio. “It’s too valuable,” he says. “It has such a history it will be worth a lot of money when it goes on eBay.”

With age 80 drawing nigh, Shelton shows no signs of putting the Princeton up for sale any time soon. Between cruise ships, clubs, and recording, he maintains a schedule that would daunt a much younger man. “It forces me to keep my chops up,” he explains. “When I lay off, I can feel it, so I’m still very active.”

Louie Shelton Essential Listening

“Last Train to Clarksville” by the Monkees

When the Monkees’ 1966 debut single leapt to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, not only did it launch the band’s career, but Shelton’s as well. His phone started ringing off the hook once L.A. record producers discovered who had actually played the song’s sparkling signature riff and jangly instrumental bridge.

“Hello” by Lionel Ritchie

In this must-see video, Louie takes us through his epic solo and describes how he constructed and performed it. Shot in Shelton’s studio, it’s a four-minute master class in phrasing and melodic construction.

Stevie Wonder’s “Too High” by Louie Shelton

Four minutes of sweet humbucker magic! Watch Shelton play “Too High” from his latest instrumental album—a tribute to Stevie Wonder called Higher Ground. Slippery octaves, funky rhythm moves, snappy single-note lines—they’re all here, played with the relaxed confidence that defines Shelton’s session work.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)