"Yeah, Pino, do you have this big archive of stuff?" Blake Mills is ribbing Pino Palladino about the question I just asked, but it's something we're both very interested to know. "Yeah, I do," the legendary bassist exasperatedly replies, as if he's finally let out the secret that he's been composing and recording original music throughout four-and-a-half decades, keeping it to himself until now.

At 63, Palladino is pretty deep into his career to be releasing his first album of original material. But since the early 1980s, he's been busy contributing to recordings by so many other artists that it really isn't surprising he's just finding the time. "I've waited this long to record something of my own because it's all about space. I've been working on other people's music, which is so different," he says.

Palladino's credits read like a list of the best-selling artists of each decade he's been active, starting in the '80s with Gary Numan, Phil Collins, Elton John, and Don Henley, moving into the '90s alongside Melissa Etheridge, Carly Simon, Eric Clapton, and Michael McDonald, tracking for John Mayer, Erykah Badu, and D'Angelo in the 2000s, and with Keith Urban, John Legend, and Harry Styles in the 2010s—with many, many, many others along the way.

Off The Cuff

What's even more impressive than his resume is that Palladino seems to leave his mark on every session he plays. His nuanced feel adds such a personal touch that it seems as though he puts himself into every note in a way that is instantly recognizable, no matter what style of music he's performing.

On Notes with Attachments, we're finally invited to hear what kind of music has been marinating inside Palladino's head all these years, and the result is exceptional and almost indescribable for its unique sound. Featuring the bassist's compositions, the album was brought to life in collaboration with Mills—who produced, co-wrote, and played on it—and with assistance from heavy-hitting musicians, including keyboardist Larry Goldings, saxophonist Sam Gendel, and drummer Chris Dave.

Throughout the album's 31 minutes, Palladino, Mills, and company throw down an eclectic stew of references that stretch from jazz to minimalism to hip-hop to global sources that span from West Africa to South America. This broad swath of influences makes for a thrilling and dimensional listen, while supple, expert-level grooves provide a warm and cohesive foundation. Every track exhibits high-minded production values that make the album feel futuristic, and we'll be awfully lucky if this is a glimpse of where instrumental music is headed.

"I've waited this long to record something of my own because it's all about space."—Pino Palladino

When pressed about it, Palladino sounds as if the idea of recording an album of his own is something that's always been lingering in the abstract, a possibility that made sense but remained undefined. It wasn't until the last few years that the pieces of the puzzle started to coalesce, as he cut the rhythm tracks for his Fela Kuti-inspired number "Ekuté."

"That came out of something I recorded with drummer Chris Dave at my house in London," Palladino explains. "He and I met in 2009 or so, when we were working on Adele's 21, and started getting together. We recorded that without knowing what we would use it for—whether it would be something of mine or some kind of collaboration between he and I. I showed it to Marcus Strickland, who added the bass clarinet arrangement."

After meeting Mills while working on John Legend's Darkness and Light, Palladino played it for the producer/guitarist, who helped finish the track and explains, "When I played my guitar part on it, I was trying to think like a baritone sax player, where the singer left the band and the baritone sax is playing the melody."

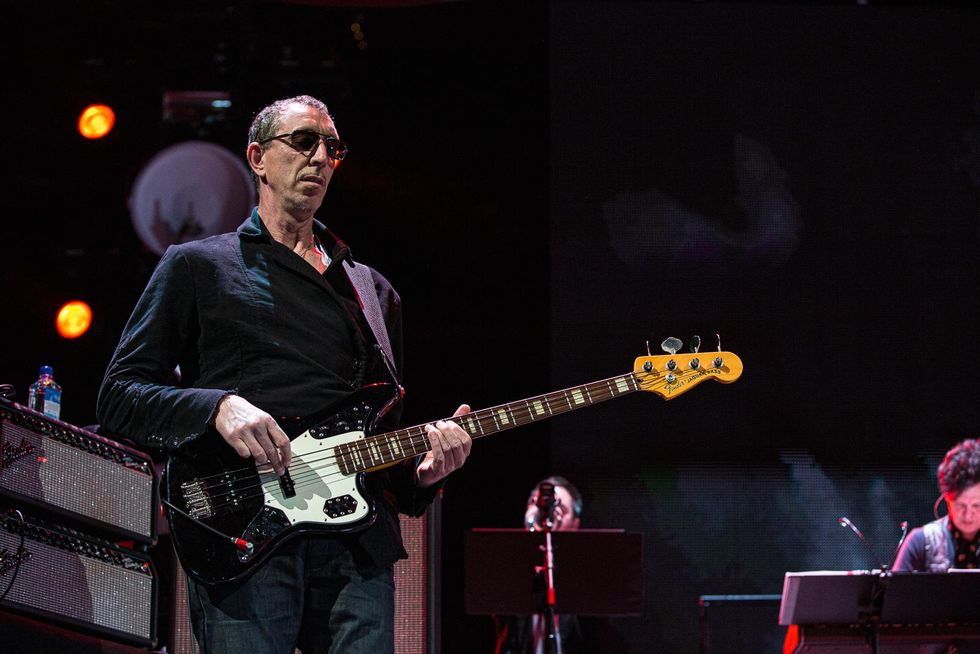

Pino Palladino's career is packed with blue-ribbon studio and stage credits. Here, he stands with the Who, with whom he toured from 2002 to 2017, playing a Fender Jaguar Bass.

Photo by Tim Bugbee/Tinnitus Photography

Pino Palladino's Gear

Basses

- 1961 Fender Precision

- 1963 Fender Precision

- 1960s Magnatone Hurricane

- 1977 Music Man StingRay fretless

Strings

- La Bella Flatwound (various gauges)

- Thomastik-Infeld Flatwound (various gauges)

Mills goes on: "When Pino played that for me, that was the first time that I got to hear Pino as a composer." Intrigued by the possibilities he heard, Mills encouraged the bassist to continue their collaboration, which became an essential part of the album's creative process. Palladino started to present ideas to Mills in various states of completion: some were one or two parts, while others were full demos. "We were uncertain what we were working on," says Mills, adding, "I'm not really sure what we've made or what kind of music this is."

Uncertainty was an asset throughout the recording process, as the two musicians figured out what they would work on and what they could experiment with. Palladino first recorded the track "Soundwalk" in 2000 while snowed in during his tour as a member of D'Angelo's backing band, the Soultronics, on the Voodoo tour. Palladino laid down bass, guitar, and drum machine in his hotel room, and passed it on to his Soultronics bandmate, Jacques Schwarz-Bart, who added a full horn arrangement to the minidisc recording. While he loved the track, the original disc has since gone missing, and the bassist only had an MP3 of the song. Although he could have re-recorded the whole thing, Palladino felt there was something extra-special about Schwarz-Bart's part that would be impossible to recreate.

Kismet intervened when Mills received a demo of a new app called Rebalance, which features a technology that allows users to essentially create stems from full recordings. Mills' friend, software developer Dave Godowsky, was in the studio to demo the app for Mills when Palladino walked in and played them the demo for "Soundwalk." They used Rebalance to extract the horn part and, while Mills explains that Rebalance was capable of a clean extraction, they became inspired as they "toggled between the parts" and messed with the app's settings. The version of the horn arrangement they ended up using allowed artifacts of the original recording to bleed onto the refurbished track, creating a sound Mills describes as "almost anechoic."

TIDBIT: More than 40 years of composing and two-and-a-half years of on-and-off recording went into the creation of this album—the first to feature Pino Palladino's name on its cover.

Then, they used this extracted track to build the new version of the song, with contributions from Gendel, Goldings, and keyboardist Bruce Flowers. The result is a piece of cut-up minimal funk that sounds like a post-J Dilla update to Teo Macero's work on Miles Davis' On the Corner. Different colors of horn and keyboard parts interact sporadically across the stereo field, while weird percussion bits played by Mills groove with Palladino's distinctive bass bubble at the song's core.

It must have felt like advanced mathematics for Palladino and Mills to coordinate their busy schedules, but they found time to work on Notes with Attachments over the course of about two-and-a-half years. "We'd go in for a couple weeks here and there, and sometimes we wouldn't even have time to listen back to something we'd worked on for a couple weeks," says Palladino.

"When I was playing with Pino, I was really trying to watch him and be inspired by what he was playing and how he was playing."—Blake Mills

"Some music you can go in the studio and record quickly. I don't know what this record would sound like if we had done that," says Mills. Since both were constantly immersed in other projects, they had space to step away from the album, giving them perspective to hear their tracks with fresh ears. This patient workflow inspired experiments and challenges that might have never happened if they'd recorded the album faster.

One of Palladino's biggest experiments in making Notes with Attachments was to bring his melodic sense to the fore as he explored approaches to composition and sound that departed from his usual work as a session bassist. On the West African-inspired "Djurkel," Palladino decided to capo up and multi-track his playing in three bass parts, inspired by the 1-stringed instrument that gives the track its name. The song's looping bass figures interweave with each other to create a distorted melody that resembles a mbira ensemble and challenges the role of the bass guitar.

When talking about this composition, Palladino is quick to say the album is not about virtuosity or technique, but Mills interjects. "I think Pino is being humble here," and goes on to explain how the way the bassist phrases his lines and shapes his notes throughout are all informed by the overwhelming depth of his experience. Basically, Palladino puts it all into his playing, and it shows.

After co-forming an early version of the band Dawes, Blake Mills went on to become a touring and studio guitarist, and then a producer. Here, he plays a headlining gig at L.A.'s El Rey Theatre in 2014.

Photo by Debi Del Grande

Palladino is quick to throw the compliment back to Mills, who, throughout our interview, seems to be looking at the big picture of the album and thinking from the perspective of a producer. While Mills is well known as a great guitarist, he often avoids being overtly guitaristic in his extremely prolific production work. His instrumental contributions are mostly understated throughout Notes with Attachments, but there are notable spots where his playing shines, as Palladino points out. The most obvious is the percussive breakout solo he takes on "Man from Molise." There, he's playing a Cuban tres, not a guitar, but that speaks to his instrumental role on the album. While Palladino has the low end on lock, Mills takes an open-eared approach, playing everything from djurkel to Coral electric sitar to guitar synth.

"When I was playing with Pino," Mills says, "I was really trying to watch him and be inspired by what he was playing and how he was playing." It's charming to hear each of these two giants of their instruments defer so strongly to the other's abilities. And it's no show. These guys both know how great the other is, and despite all the time they spend in the studio working on music, they remain excited by the process. While Palladino and Mills clearly love discovering new sounds and creating new tracks, it's also clear they just like to hang out and make music together.

Pino Palladino + Blake Mills + Sam Gendel - Man From Molise (Live)

In December 2020, Pino Palladino, Blake Mills, and saxist Sam Gendel got together at L.A.'s historic Sound City Studios to create live versions of songs from Notes with Attachments. "Man From Molise," from that session, is more subdued than the version on the album, but illustrates some of what each of these musicians brings to the table. Check out Palladino's lead melody starting around 30 seconds, which lasts until he introduces the repeating figure at 1:40 and uplifts the song's simmering 7/4 groove as it supports Mills' soulful lead.

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.