If you haven’t yet heard of Blake Mills, the odds are strong he’ll make your playlist before the year is out. A founding member of the Malibu rock band Simon Dawes, Mills released his brooding solo debut Break Mirrors in 2010. He’s been in demand ever since as one of L.A.’s most inventive and versatile backing guitarists—in the studio and on the road with such heavyweights as ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons, Lucinda Williams, Beck, Fiona Apple, Jenny Lewis, Norah Jones, Kid Rock, Band of Horses, Danger Mouse, and many more. Barely 28, he’s also turning heads as a singer-songwriter and producer (Alabama Shakes have him onboard for their next album) with a quirky, romantic flair for rootsy influences from all over the map.

Put simply, Mills is a musician’s musician with riffs, licks, slides, and fingerpicking tricks galore. In early 2012, he caught the attention of none other than Eric Clapton, who heard Mills’ slide work on a cover of the Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows” and called Derek Trucks, thinking Trucks was the guitar slinger in question. That in turn prompted an invite to the 2013 edition of Clapton’s Crossroads Guitar Festival, which Mills gleefully accepted just as he was starting to write songs for his latest studio outing, Heigh Ho.

As its title suggests (in the key of Disney, to be sure), a lot of work went into crafting the new album. “I was after a sound that I don’t really get to hear on a lot of records made today, at least by people my age,” Mills says thoughtfully. “There’s a tendency to get fucked-up, lo-fi sounds—and that’s great, and I love that, and some of my favorite records sound that way—but I think there’s a real mystery now to sonic depth in recording. It’s like the depth of field in an impressionist painting that’s meant to look realistic. There’s a parallel for that in recording, and it’s about making a sonic experience that will transport the listener into the room, with what’s going on, and into a different environment.”

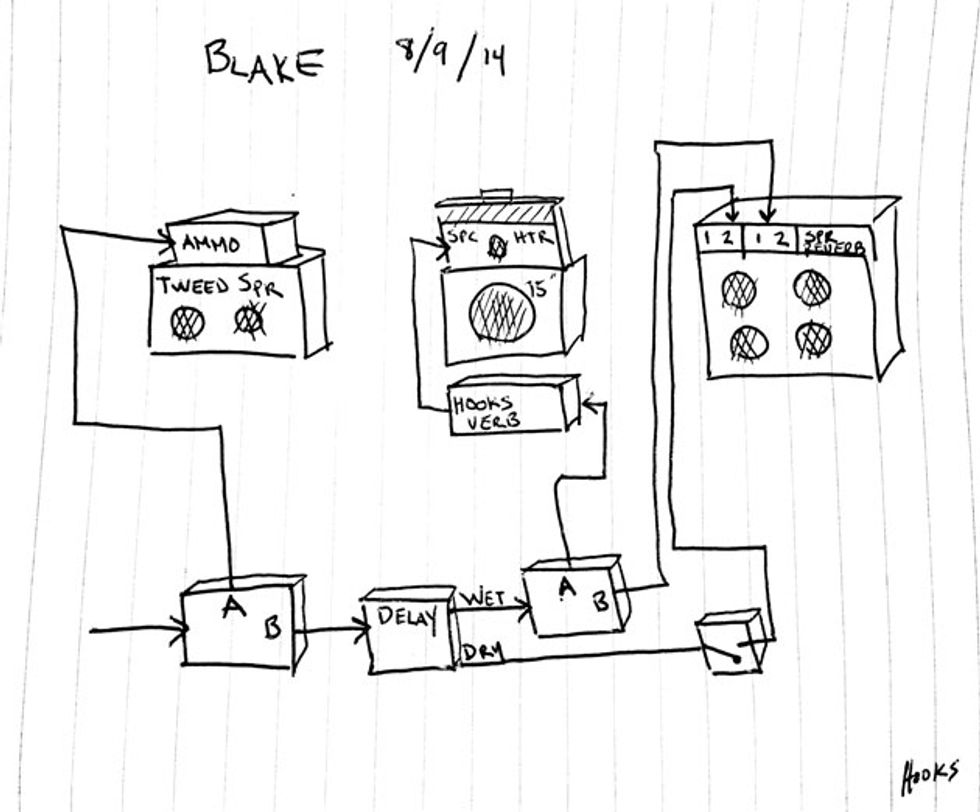

Largely tracked in Studio B at Hollywood’s fabled Ocean Way Studios, Heigh Ho channels an after-hours, introspective, and distinctly California folk-inspired palette of emotions. (Mills even parked by the beach late at night to cut some of the lead vocal tracks with a laptop setup in his car.) Mills stretches out with equal abandon on electric and acoustic guitars, including a legendary ’52 blackguard Telecaster owned by Jackson Browne, as well as a tiny century-old, gut-string acoustic that weaves through half the album. Fittingly, he plugs into a fleet of exotic amplifiers and cabinets, most of them custom-built by local amp tech and electronics whiz Austen Hooks, who also designed Mills’ stage rig for his current tour [see diagram].

But what really makes Heigh Ho the complete package is the band—specifically, the core trio of Mills, Don Was on bass (Mike Elizondo grabbed the bass on two songs), and veteran session ace Jim Keltner on drums.

It’s like the depth of field in an impressionist painting that’s

meant to look realistic.

“We always tracked live as a trio,” Mills explains. “We’d set up and I’d play through the tune for them, and then we’d just start doing takes. I wanted the basic tracks, those live performances, to have a lot of space in them, so sometimes we would whittle down and simplify, but there weren’t a lot of ‘parts’ to begin with. This is a performance space record, and the spirit of the performances is definitely influenced by economy, I think. We did what we all felt was appropriate for the song, but other than that, there was a pretty high ceiling as far as what was allowed.”

Heigh Ho brims with a lush, wide-open sound that in some instances recalls touchstones like Jackson Browne’s For Everyman, George Harrison’s Living in the Material World, or even Led Zeppelin’s Houses of the Holy. From the sparse, vintage Magnatone vibrato figure of the lead-off single “If I’m Unworthy,” to the infectiously tuneful shuffle and flawless picking of “Don’t Tell Our Friends About Me” (with Fiona Apple taking a riveting guest turn on harmony vocals), to the beautifully string-washed “Half Asleep,” it’s every bit the rich sonic experience that Mills sought to capture.

I first caught you in a YouTube clip playing Lucinda Williams’ “I Just Wanted to See You So Bad,” and you struck me as a player who wasn’t enamored of the spotlight, but the spotlight would find you eventually.

[Laughs.] It’s been an interesting last few years. Things have really started to pick up around my songwriting and making solo records, and producing and session work. But I feel like it’s all fed by just being a guitar player and a musician. When I first started playing guitar, it was because I was watching way too much MTV and was completely obsessed with Kurt Cobain. But at some point within the first year or two of learning how to play Nirvana songs, it kind of clicked over into something else.

Around that time, I heard Bob Brozman play guitar. I think my dad took me to see him at McCabe’s guitar shop in Los Angeles. Bob was always kind of a purist in terms of the acoustic-ness of the resonators he played, and after that show, I was completely hooked on these influences that came from world music and acoustic music. There was a part of me that still really loved Nirvana and Soundgarden and Metallica, and then at the same time, this other part of me couldn’t get enough of [sarod master] Ali Akbar Khan or Djeli Moussa Diawara—the kora player that Bob made a record with.

It wasn’t until quite a while later that I just accepted it was okay to like both things, you know? I didn’t have to make a decision about who I was, or what kind of musician I was. I think it took a load off my back, because I don’t really feel like today I have any more responsibility to make a decision as to whether I’m a guitar player or a producer or a singer-songwriter. I can just allow myself to be all these different sides of the same coin.

Blake Mills’ current touring rig, designed by Austen Hooks. Clockwise from upper left: (AMMO) Ammo Can spring reverb and brownface vibrato, custom built by Jo Anne at Victoria Amplifier; (TWEED SPR) ’54 Fender Tweed Super; (SPC HTR) “Space Heater” amp custom built from a military-issue film projector; (HOOKS VERB) custom-built spring reverb; (SPR REVERB) ’66 Super Reverb with ceramic Jensen speakers; pedalboard with a series of Radial ABY switchers and a Maxon AD-999 delay pedal.

You’ve worked with a lot of people in a pretty compressed period of time. Is there a secret to a successful collaboration?

It always seems to me like it bears a resemblance to having a conversation with somebody. And even if you don’t have something to contribute, there’s something to be said for how you listen, and how you participate. Even if I don’t have a musical opinion to give, at least there’s something I can do—a sort of musical nod, saying “Mm-hmm”—that can help keep the conversation going, you know?

That’s why touring with Lucinda was such a dream, because her music is so well written for a guitar player—these wide-open chord changes, where you can see the next verse coming. Then I went straight into playing with Fiona, and her music is sort of the opposite—like a stream of consciousness with a series of left turns—so you really have to commit. It took me a while to wrap my head around that because there’s hardly any guitar on her records. But it actually became the perfect gig for me, because I got to have all this fun making the guitar do things that were very un-guitar-like, which is a big favorite of mine.

There’s a massive scope to this album, starting with your choice of studio.

Well, I’ve done a few sessions at Ocean Way over the years, and always had a magical connection to the way Studio B sounds, especially drums. I wanted the flexibility—really just the sound of what goes on in that room, because I’m in love with the way Jim Keltner sounds in there. And I think the spirit of working with Jim is sympathetic to how the sessions went. As soon as you start directing him, you lose something about his spontaneity that nobody else has. Hearing how he gets out of a conundrum musically is one of my favorite moments. It’s like he’s an escape artist.

Blake Mills' Gear

Guitars

’52 blackguard Telecaster owned by Jackson Browne

Goya Rangemaster

Antique gut-string acoustic

Homemade Coodercaster-inspired guitars

Amps and Effects

’54 Fender Tweed Super

Custom Victoria Ammo Can spring reverb and brownface vibrato

Custom “Space Heater” amp built by Austen Hooks

’66 Super Reverb sporting Jensen speakers with ceramic magnets

Radial ABY switchers

Maxon AD-999 analog delay

Strings and Picks

Various D’Addario electric, acoustic, and nylon sets

You’re getting a ton of different sounds here too. What were some of the guitars you used?

I’m a massive Telecaster fan because it’s the most straightforward and versatile guitar I’ve ever known. The ’52 blackguard Tele that I’ve been borrowing from Jackson Browne for a few years now has an interesting history. It was on a ton of his early records, and Waddy Wachtel and David Lindley and all these guys have played it.

I don’t play slide on the Tele very much—that’s almost always on my Coodercaster-inspired guitars. One of them I built with a guitar tech friend of mine named Mike Cornwall. The bridge pickup is similar to what’s in Ry’s guitars, but the neck pickup is from a Guyatone. I’m sure the secret’s out on those, but for a while I couldn’t find any information on them. They sound incredible, and they’re pretty different from the Teisco pickup that a lot of people put in that position when they’re making a Coodercaster. Bill Asher built my other one, and I use both of those for slide almost exclusively.

It’s a different technique for slide playing on a Fender-style fretboard, as opposed to a Gibson, which is relatively flat. The humbucker also makes a huge difference for sustaining the slide and shaping the notes, so any of the humbucker-style slide that you hear was done on a Les Paul that I’ve had since I was about 18. It was a gift from Dickey Betts, and it’s the best Les Paul I’ve ever heard. I even tried to find something to beat it, because I really didn’t want to tour with this thing because it’s so valuable. I took it to the vintage room at Guitar Center, and it just beat out everything. It may be a terrible idea to bring it on the road, but all these instruments don’t sleep in the trailer [laughs].

You get a huge Jimmy Page-style reverb on “Just Out of View.” [Engineer] Greg Koller says you had a 15" extension cabinet set up in the big side room with a pair of Neumann KM 53 room mics on it.

Right, and I played that on a Goya Rangemaster—an unusual-sounding guitar. The pickups are split in half, and you’ve got all these electro-mechanical switches for dialing in different combinations. But if you push the switches halfway down, you’re only monitoring three strings of the guitar. The other strings don’t have a pickup on, so if you play them, you’re just getting the sympathetic vibrations through the strings that do, so you get this really spooky reverb. It’s like tuned reverb—a really cool sound that I just happened to find accidentally. I think I used that for the fuzzed guitar—that Keith Richards-y lick—on “Gold Coast Sinking,” too.

On the song “Just Out of View,” Mills played a Goya Rangemaster, which he calls “an unusual-sounding guitar.” By pushing the pickup switches halfway down, he was able to get a spooky effect. “It’s like tuned reverb—a really cool sound that I just happened to find accidentally.”

Who designs your amps and cabinets?

They’re made by a fella named Austen Hooks. He finds a particular model of these old Bell & Howell film projectors, and he makes amps out of the amplifier section. Most of the reappropriated boutique amps I’ve heard in this category have all had a sound that would be good for something, but everything Austen works on, he has such a good ear that those projector amps are good for everything that I do. They’re really well rounded, and the arc of the note is just exactly what I want it to be. It doesn’t have too much of a nose on it, and it’s not too compressed to where you can’t get it to cut through a mix—it’s just this nice area in between.

So we’ve spent a lot of time going back and forth to shape the sound of the amps, and going through different sets of old speakers for the cabinets he’s building. The speaker configuration, the model, the year—all that has been a journey that we’ve been going through together for the last year-and-a-half or so.

Tell us about your fingerpicking technique. It really comes out with a thick-sounding twang on “Shed Your Head.”

I would say the time that I spent with Bob Brozman was huge in getting me to put down a pick. He would use fingerpicks because he was playing a resonator, but fingerpicks were always cumbersome for me, so I would try to compete with the volume that he was getting by just using my fingers, and my fingernails stood no chance. If they even grew out, I’d break them. Over the last two years, my fingernails have gone back down to a more masculine length [laughs], so I’m using a little more of the flesh again.

YouTube It

Blake Mills covers Lucinda Williams’ “I Just Wanted to See You So Bad” for the Voice Project.

I know you’ve used D’Addario strings for a long time, with a lot of different gauges—but what about some of the different tunings you use?

“Seven” I think is just in open Eb or open B. Most of the slide stuff is in some variation of open E, whether it’s tuned down or not. “If I’m Unworthy” is in open C#. That one is like my second language.

There’s definitely a strange tuning for “Don’t Tell Our Friends About Me”—one that came about because I really wanted this song, which is in Bb, to use the open D string for the third. But then I had to figure out how to use the top two open strings. To get to the nearest notes, I dropped the B string down to Bb and raised the high E string up to F. There’s no familiarity with that tuning. Nothing carries over. It’s a totally different alphabet, but it’s a cool one [laughs], so it’s nice to feel like you’ve invented something on an instrument that’s been around for so long.

You’ve worked for a while now with Fiona Apple. How did you bring her to “Don’t Tell Our Friends About Me”?

That’s probably the oldest song on the record. I actually never had any harmony in mind for it, but when we did a tour last year that was kind of a collaborative show, she had this harmony part for it—and it wasn’t just a harmony. It was like the story of the song changed by having a female perspective and character in the song, and she took that further, and I think it inspired her to write the counterpart lines at the end. She sort of represents the female side of the song, and it changes the meaning of it in a way that was really exciting. It was a song that I’d had for a couple of years, and it was such a refreshing experience to have that come about, and the timing of it was perfect because it was just at the end of the line before we had to wrap the record up.

That one has such a familiar melodic shape with the phrases—that kind of country-and-western shape. I really enjoy singing harmony, almost more than lead, because I just like the sound of my voice as a background voice. But when it came time to do that song, I knew I wanted to do it as a duet. And Fiona’s voice—the quality of her voice, especially after listening to my voice so much—you can really hear what the texture of her instrument does to a song. I think she really elevates it pretty significantly.

Making Waves: Recording Heigh Ho at Ocean Way’s Studio B

If you’re an up-and-coming artist, these days it’s probably more than a bit unusual to have a sizable recording budget burning a hole in your pocket, as Blake Mills did to make Heigh Ho. But if you do hit the big time, it certainly helps to have a veteran producer as prolific, exacting, and thorough as Jon Brion on your speed dial. “I wanted an engineer I could trust,” Mills says, “and I knew if I asked Jon for his ideas, then everything was going to be in good hands.”

True to form, recording and mix engineer Greg Koller knows his way around Ocean Way. “I spent about four or five years there, just before Allen Sides sold it [in 2013],” he notes, “so I’m very familiar with Studio B. Plus Blake likes some of the records that have been made there, so it was the obvious choice.” Designed in the 1960s by the legendary Bill Putnam, the live room is known for its sawtoothed walls and balanced surfaces. “It gives back what you’re putting in the room, but in a very pleasing way.”

For the basic tracking of the core trio—Mills, Don Was (bass), and Jim Keltner (drums), and Mike Elizondo sometimes subbing on bass—Koller set up his mics so that everything he caught in the room would make it to the recorded take. “That was really important, since they all play together so well,” Koller says. “I set Blake up on the left side of the room with a little guitar station. We put a few gobos around him to keep his strumming and singing out of the room mics.”

Koller placed one of the Hooks amps next to the drum kit, with a Neumann U 47 pointed at the 12" speaker. “On a few tracks, if he was playing a little bit louder, I had an RCA 44-BX a few feet back, just to capture a little more body with, I would say, a closer room sound. And then the room mics were Neumann M 50s, to get the overall room tone with the drums, guitars, and anything else that was being played live.”

Isolated in a side room just off the main tracking room, a 15" extension cabinet was set up specifically to capture lush, wide-bodied guitar tones. “That room is pretty much the length of the whole studio, and about half as wide. We had a U 47 or a U 67 on the cabinet, and then another pair of Neumann KM 53 room mics capturing just that sound. You can hear it on the song ‘Just Out of View,’ which is very big and wide.”

All the basic tracks went to Pro Tools at 24-bit, 96 kHz resolution. “In the mixing stage, Blake would do some editing and we’d go song by song to decide if we wanted to do more production and maybe change the tones a little bit with analog gear. I have a lot of old vintage tube compressors and EQs, and I have access to an old EMI console, which we used on the tracking dates."

Of course, with an album of this scope, analog tape machines came into play at some point—as did a little bit of harmonic convergence. “A few songs might have an acoustic guitar he wanted to sound a little older and crustier, and overdriven a little bit, so we’d bounce it off my Ampex 602 1/4" machine,” Koller says. “'Don’t Tell Our Friends About Me’ had a few like that, and so did ‘Three Weeks in Havana.’ That one was cool too, because if you notice the weird reverb going on, he’s singing and playing in the room, but I put a contact mic on one of the guitars hanging on the wall behind him. When he sings out, the guitar vibrates and gives it this odd harmonic reverb.”

In the end, Heigh Ho is a testament to the spirit of experimentation, all in the diligent pursuit of a particular sound that Mills had in his head. “Blake is really interested in playing with space, reverb, and different environments,” Koller observes. “That doesn’t happen much nowadays. Everything is processed through plug-ins, and he wanted to avoid that and make something that’s hard to achieve. You have to work for it. It’s bigger and it’s more natural, and it encourages you to listen and get more immersed in it. You can’t just throw the latest plug-in on it. You actually have to sit in a room and play it and record it. That’s the only way you’re gonna get it.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)