Somewhere on a two-lane blacktop between Detroit and Indianapolis, Samantha Fish is cruising along with her band, thoroughly in her element as she looks ahead to her next gig. “On the road, always!” she says over the crackle of her cell phone. “But yeah, that’s why we do this: Music is the universal language that we all speak and can understand, and there’s something people need in that, you know?”

She’s just 28, but after a decade of playing in front of all kinds of crowds, from the smallest clubs to the biggest festivals, Fish radiates an upbeat worldliness that has seeped into her music—a rangy mix of garage rock, blues, country and soul. Along the way, she’s opened for Buddy Guy at his Legends club in Chicago, shared bills with Johnny Winter, George Thorogood, Corey Harris, and Tab Benoit, and garnered praise from The New York Times as “an impressive blues guitarist who sings with sweet power.” It’s been quite a journey from her hometown in Kansas City, Missouri, where she started out jamming on drums with her father, her uncles, and their friends before switching to guitar when she was in her mid-teens.

“My father played guitar,” she says, “and it’s funny because the style of music would change based on whoever was over at the house. We listened to the radio growing up, so there was all this rock ’n’ roll, and if his brothers were over, they’d be playing guitar to Black Sabbath or Black Label Society—some kind of metal. And then some friends might play bluegrass or West Coast swing or country music—Americana, songwriter-type stuff. And my mom sang in church, so you can see how the lines are connected.”

Primarily self-taught, she picked up everything she could from her idols—Stevie Ray Vaughan, Keith Richards, Angus Young, Slash, the Heartbreakers’ Mike Campbell—before she discovered the North Mississippi hill country blues sound of R.L. Burnside, Junior Kimbrough, and the Fat Possum label. At 17, she started hanging around Knuckleheads, the hottest blues-country saloon in Kansas City, and eventually drew the attention of owner Frank Hicks, who got her time onstage and the chance to cut her teeth with a slew of different blues and roots artists, including Benoit and Michael Burks. In 2010, on the recommendation of St. Louis blues guitarslinger Mike Zito, she landed a deal with the late Luther Allison’s label Ruf Records (founded in 1994 by Allison’s manager, Thomas Ruf), and she’s been making her mark ever since.

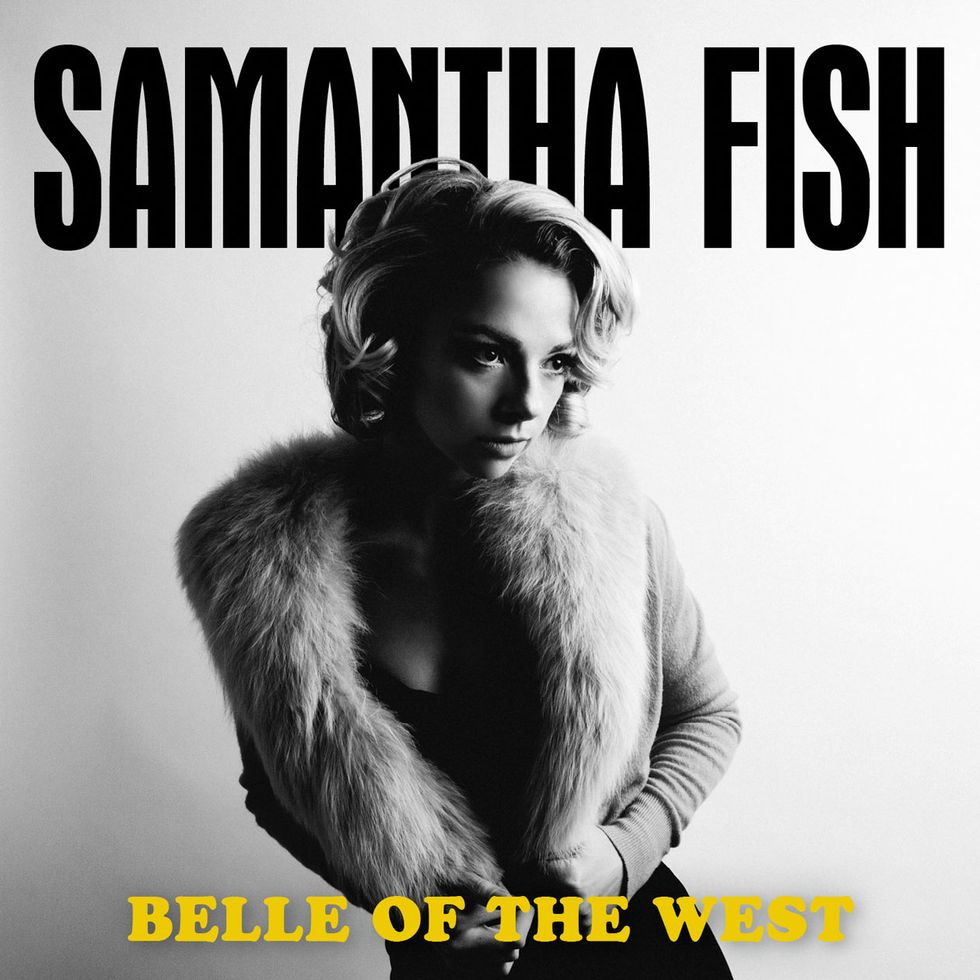

Belle of the West is Fish’s latest album, with a history of its own. Recorded near the end of 2015, the sessions were produced by the North Mississippi AllStars’ Luther Dickinson at his father Jim Dickinson’s famed Zebra Ranch studio in Coldwater, Mississippi, just south of Memphis. At first, Fish and Dickinson had conceived of a more acoustic-based follow-up to 2015’s Wild Heart, which they’d also worked on together in the fall of 2014. But as more guest musicians came into the fold—including singer and fiddle player Lillie Mae, known to many for her high-profile stint in Jack White’s Lazaretto band, as well as Mississippi roots guitarists Lightnin’ Malcolm and Jimbo Mathus—the album took on a larger scope. [See sidebar, “Meanwhile, Back at the Ranch.”]

During the session, with plenty of encouragement from Dickinson, Fish made some discoveries while playing hollowbody guitars—particularly the Gibson ES-390. The fat, feedback-hugging tone is a departure from the thinline Tele-style sound she gets with her custom Delaney “Fish-o-caster,” and the new tonal direction inspired her to dig deeper into the underlying melodies of the songs before she tracked her solos.

While cutting guitar tracks for Belle of the West, Fish’s Category 5 amp was in Zebra Ranch’s small room, and she would stand close to the large room, where Luther Dickinson would crank the backing tracks to simulate a live atmosphere.

“You know, we went into the studio with the best intentions of making an acoustic record,” Fish says with a laugh, “but I’ve got Luther in there with me, and we’re both guitar players, so we ended up with something a little heavier, and I’m glad we did. He introduced me to hollowbody guitars and the different feedback you can get when you ring out certain notes, and that really influenced my solos a lot. So it’s a semi-acoustic record—that’s the term we finally landed on when it was all said and done.”

As luck would have it, Belle of the West was tracked quickly—often just first or second takes with the full band, which also features Amy LaVere on upright bass and Tikyra “TK” Jackson (of Southern Avenue) on drums, playing live on the floor. But almost as soon as the album was mixed, Fish sensed the urge to get another project out of her system.

“As a little time passed, I felt like we needed something higher octane to put out beforehand,” she says. She hooked up with Detroit-based producer Bobby Harlow to tap into the no-frills, garage-rock spirit that inspired her as a kid. “That’s how the Chills & Fever concept was formed. We recorded with members of the Detroit Cobras, brought in a horn section from New Orleans, and put together this really high-energy big band to do soul and rock ’n roll covers from the ’50s and ’60s.” When stacked against Belle of the West’s rootsy, soulful sound, Chills & Fever, which was released in March 2017, sounds unusually punked-out and jagged. “I know they’re dramatically different,” Fish explains, “but that was the idea. It’s two different concepts, Detroit and Mississippi, but it made sense to put out these two albums in one year for just that reason—because they’re such concept records.”

Having recently relocated to New Orleans, Fish is poised to expand her musical horizons even further, but she still feels the pull of the Mississippi blues, no matter where she calls home. “To me, it’s the core of rock ’n’ roll music. It’s this unpolished, guttural, raw sound that people seem to gravitate to over and over again. It just gets redone and modified. It’s weird how we kind of remove all the slickness every few years, and come back to this real, almost aggressive, thing. I think it’s just because that’s where our hearts are, you know? That authenticity resonates with people.”

Samantha Fish digs into one of her Delaney custom guitars: a 512 hollowbody that she had built after the sessions for Belle of the West. Her other Delaney is her signature Fish-o-caster. Photo by Dan Locke/Frank White Photo Agency

What was it like for you to be in the same room with all these great players to record Belle of the West?

I think for that session, the first day, I walked in feeling just super-intimidated, because I knew all these really great musicians were there to make my record, so I felt like I had to get my shit together. But once you settle into it, you learn a lot from those kinds of sessions. I’m just watching and taking it in: like, how do they approach a song? I think I’m a live player—I mean, that’s what we do all the time—so I’m not as seasoned in the studio. Obviously there’s a different approach to making records than playing live. You have to think more melodically, and I’m starting to do that more in my live show, too. That’s something Luther taught me.

Do you mean thinking outside a traditional blues pentatonic scale, or something different?

Like, not so many freaking notes, really. Quit with all the licks and all the tricks, because they have no place on the record. That’s just the way it is. And Luther has such a great way of leading the song and letting the melody grow into something really beautiful and big and dynamic. That’s one of my favorite things about him. He plays so dynamically and melodically, and I learned that from watching him. It’s something I’m still working on.

How did you meet Luther for the first time?

Well, before Wild Heart was even a concept, my manager and I were talking about who we would want to work with next as a producer. We ran down a list of key people, and I’d just heard the North Mississippi Allstars’ World Boogie Is Coming for the first time. I found out that Cody and Luther [Dickinson] had done it themselves, and I liked the sound of it—how they utilized different guitar tones, and how everything has this modern, contemporary sound, with drumbeats that are really danceable and exciting. So we just made a couple of phone calls, and he was into it. [Laughs.] I couldn’t believe how easy it was. So we did Wild Heart in 2014, and then we came back together for Belle of the West.

Did your signature Delaney thinline figure into the making of this album?

I’ve got a couple of them that I use a lot live. But my newest guitar, the Delaney 512 hollowbody, I got because of the Belle of the West sessions. After making the album, I thought I needed a big hollowbody guitar that really resonates, because the guitars Mike Delaney had made for me in the past were the Telecaster-style thinlines. For the acoustic stuff, everything you hear is my Taylor Koa, the K24ce. And with Chills & Fever, I branched out again and got the Alpine White Gibson SG. That was a gimme for my childhood self, because I was a big Angus Young fan, and still am. So now the guitar arsenal is so vast, it’s ridiculous!

Guitars

Delaney signature SF1 “Fish-o-caster” (thinline T-style, with Amalfitano humbuckers and fish-shaped soundhole)

Delaney 512 hollowbody

Gibson SG (late model, Alpine White)

Fender Blacktop Telecaster

Bohemian oil can guitar

Stogie Box Blues 4-string cigar box guitar with P-bass pickup

Dean thin-body electric resonator

Taylor Koa K24ce acoustic guitar

Amps

Category 5 Amplification Andrew 2x12 combo with matching extension cabinet

Effects

Analogman King of Tone overdrive

CAST Engineering Casper delay

CAST Engineering Pulse Drive tremolo

Electro-Harmonix Micro POG

MXR Carbon Copy

ZVEX Fuzz Factory

Strings and Picks

D’Addario Regular Light strings (.010–.046)

1.0 mm picks (no brand preference)

Various brass and glass slides

And you’re endorsed by Category 5 Amplification.

Yeah, for about five years now. I’m a creature of habit, when I find something I really like. I have people tell me, “Oh you should try this, or try that,” but I’m just stuck on this one. I feel like it gives me a really natural amplified tone. That’s just my tone. Don Ritter does a really good job with old-school wiring and tubes. I mean, to me nothing sounds better. I used a Fender Super [model 5F4] before I had a Cat 5, and it’s funny, I bought that amp for like $300. All the knobs were broken off, and I couldn’t afford to fix it for a long time. I was 18 years old, and I played with the reverb up to 10 for like a year. It was awful! So I was really happy when I finally got the Cat 5.

It sounds like you’re using effects pretty sparingly—maybe just a fuzz on the solo for “Blood in the Water,” for example?

Yeah, it’s there, but Tab Benoit got in my brain about this, like, “I don’t use pedals, I just make the sound I need,” and that was some of the most important advice I got. I did away with my pedalboard for a long time, but I just started venturing back into it. Now I’m finally starting to reincorporate pedals for actual effects, and not as crutches like I used to use them.

You play “Poor Black Mattie” with Lightnin’ Malcolm on Belle of the West. How influenced were you by R.L. Burnside’s original version?

A lot, definitely. You know, the North Mississippi Allstars were a big influence on me when I started to play guitar, too, and the whole North Mississippi sound played a huge part in my musical upbringing, just with the Fat Possum [label] roster. I think it’s because I was so into rock ’n’ roll that when I started listening to blues, and especially when I found Mississippi blues, it bridged that gap between punk and rock. It had that rawness of what I really like in blues music, plus it has that danceable groove. I started out on drums, and I realized that everything I like basically flows through Mississippi. So when I finally discovered R.L. Burnside, it blew my mind because he was doing exactly the kind of stuff that I was into. And they’ve inspired so many modern contemporary artists—Jack White, the Black Keys, and all these incredible alternative artists. All that music stems from Mississippi, but yeah, that song in particular is definitely an R.L. Burnside, North Mississippi Allstars mash-up.

Fish says she purchased her Gibson SG because she’s an Angus Young fan: “That was a gimme for my childhood self.” Photo by Steve Kalinsky

“Cowtown” is another song that jumps out, especially because it has such a groove to it. There’s a Texas twang in there, too—a little Steve Earle maybe?

That song is pretty personal. I was in Europe and the Kansas City Royals had just won the World Series, and this was the funny part, because I was like, “I’m gonna write a real anthem about what it feels like to be from this cowtown, and how great it is.” Baseball had always been pretty depressing in Kansas City, but for the first time in my life, I witnessed the demeanor of my town change. Everyone held their heads a little bit higher. It’s amazing what something like that can do for a city.

But like everything I write, it turned out to be angsty and pissy and negative [laughs]. I started out with the best intentions to write this beautiful, positive song, and it just turned brutal. You just follow where the song takes you, and that took me to more of a “I’ve gotta get out of this town” kind of vibe. I mean, I love my hometown. Kansas City is a great place, but I think everybody has a love-hate relationship with where they grew up. And for the musical structure, I just wanted something upbeat. I was feeling really good after the Royals won, so I loaded it with upbeat country vibes, and then it all fell apart lyrically.

“Gone for Good” is a real foot-stomper that recalls Led Zeppelin III. It’s not too much of a leap to imagine a young Robert Plant singing it.

Wow, thanks! You know, I wrote that back in 2013. It was right after I recorded my second album, Black Wind Howlin’, but it didn’t make it onto Wild Heart, really because we’d been playing it live. I have this really odd oil can guitar that I tune to an open G, and it has this raspy, resonator quality, and that’s the only song I used it on. We tested it out live for a couple of years, but I just couldn’t find the right album for it. Every time I tried to go into the studio and redo it, thinking it had to be this certain way, it just didn’t vibe right.

So for Belle of the West, I wanted to completely reconstruct the song. I mean, the chord structure is similar, but the vibe is different. We slowed it down a little, and Malcolm is playing this staccato, off-kilter guitar in the background, and we’re doing the slide thing back and forth. He’s one of my favorite guitarists because he adds this whole extra element to everything. There are so many great guitar players on this record! But that was a fun one to do. I feel like it’s one of the higher-energy cuts on the album.

How does it feel when you get a groove like that locked up live?

Oh man, if it’s ever perfect, I’ll get goosebumps. It means you’ve transcended everybody counting with each other, and you’re really feeling the groove together. I mean, that’s why I play music, for just that kind of a moment. And when the band feels it with their whole heart and you’re moving as one entity, then the whole audience can join in on it. That’s really a connecting, unifying thing.

And I think that’s something that you won’t ever be able to reproduce. Everybody in the music industry can complain about their album sales dropping, but we just have to adapt to the current climate of what we’ve been given. It sucks, but it is what it is. I still value live performance, because that’s what inspired me the most when I started playing guitar. Going to see live shows inspired me to choose this career path. Records always felt a little far away. I couldn’t even touch them. But seeing this stuff happen in front of me, that’s what did it, and I don’t think that’ll ever change.

Samantha Fish puts her Delaney Fish-o-caster and Electro-Harmonix Micro POG to work onstage in France, summoning a Jimi Hendrix/Buddy Guy-inspired tone during a Jan. 4, 2017, performance.

Check out our Rig Rundown with Samantha from 2013.

Meanwhile, Back at the Ranch

Photo by Don Van Cleave

There’s an aura of legend that surrounds the juke-joint-styled studio named Zebra Ranch. Tucked away in the rural surroundings of Coldwater, Mississippi, the small complex was founded by Jim Dickinson, known as a musician for his keyboard and piano work on famed sessions with the Rolling Stones, Aretha Franklin, Bob Dylan, Ry Cooder, and everyone in between. He also made the leap into production in 1966, crafting albums for Big Star, Alex Chilton, the Replacements, Delta blues singer-guitarist T-Model Ford, Memphis country-rockers Lucero, and a host of others, and he opened Zebra Ranch as his base of operations.

After Dickinson’s death in 2009, his sons Cody and Luther, cofounders of the North Mississippi Allstars, took over the running of the studio. “There was really no formula to how we did it,” says Luther Dickinson, describing the initial approach to recording Belle of the West. “In part, that’s just because of the way the studio is built. There’s no control room; there’s a large room with three rooms that shoot out of it. And we always like to record with ambient mics, so we can capture those random encounters.”

Above all, with a tight schedule to keep, they had to record quickly. “Her vocals are live, so she’s playing and singing her heart out, you know?” Dickinson explains. “It makes it easy and fun to record when you have a great artist who’s ready to do that going in, all blood and guts and making a moment. So we cut the band tracks—drums, upright bass, keyboard, second guitar if necessary, and her acoustic—and then we overdubbed tons of backing vocals.” With singer Sharde Thomas joining Amy LaVere, TK Jackson, and Lillie Mae, many of the songs on Belle of the West have four- and even five-part vocal harmonies, all richly layered and mixed so that a song like the hauntingly soulful “Blood in the Water” takes on an even deeper sense of bluesy foreboding.

When it came to tracking guitar solos, Dickinson sought first and foremost to document Fish’s newfound embrace of the hollowbody sound. “It was really fun to watch her come up with a different lead guitar sound with the Gibson,” he says. “I love hollow bodies for their sustain, and she’s such a good player, I wanted to capture the first time she ever got that. It was a wonderful feeling, you know? It’s a whole ’nother world to someone who plays Telecasters. After that it was like, ‘Okay, we know that you can shred it, so let’s play some melodies.’ She got to reveal that side of her artistry, as opposed to just being a gunslinger.”

For the most part, Fish didn’t use headphones to track her overdubs. With her Category 5 amp set up in the studio’s small guitar room, she would stand close to the large room, where Dickinson would crank the backing tracks to simulate a live atmosphere. “For the mics, we probably used a Royer 121,” Dickinson recalls, “and the second mic varied anywhere from a [Sennheiser] 409 to a [AKG] 414 or a Telefunken. We may have had a vocal mic on Samantha, too, along with the room mics in the big room.”

To capture the woody presence of Fish’s Taylor Koa acoustic, Dickinson went with a tried-and-true method. “Usually we put a DeArmond pickup in the soundhole, and then we take a direct signal or a clean amp. That’s what we did with Patty Griffin [on her 2013 album American Kid]. Guitar players tend to like it. It was good enough for Elmore James and Lightnin’ Hopkins, right? You put that through a clean amp, and it just sounds fat.”

Dickinson is quick to point out that the goal is always to maintain the unvarnished spirit of the performance. The very idea of going back to “fix” something in the mix, whether through editing or enhancing, would be an act of sacrilege. “My disclaimer is: This is not pop music,” he insists. “I’m not trying to make anybody into anything they’re not, or cross over into anything. But if you want to make some realistic roots music that sounds good and has a good energy, that’s what I specialize in.”

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)