Somewhere at the intersection of punk, art rock, free jazz, and pop is a special place where Deerhoof comfortably resides. Satomi Matsuzaki—who moved to the U.S. in 1995, had no band experience, and found herself in Deerhoof just two weeks later—somehow manages to combine vocal duties, solid bass playing, and calisthenics. And drummer Greg Saunier is a master of economy who can do more with a kick, snare, and single cymbal than many accomplish with a vast kit.

But guitarists John Dieterich and Ed Rodriguez are the band’s conjurers. They write parts that complement and antagonize each other, often changing course on a dime. Not only do they explore any part of the guitar that makes sound—employing behind-the-bridge, above-the-nut, and beyond-the-22nd-fret techniques—but they can also execute lateral runs and speedy double-stops that go head-to-head with revered shredders. Theirs is a style that’s virtually devoid of cliché.

Dieterich joined the band in 1999, nine years before Rodriguez, but they’ve been playing together for decades—and that’s apparent within minutes of seeing them at work. A Deerhoof show is a jaw-dropping display of creativity and chops, but more than that, it’s just fun. One of the hardest-working bands in indie rock, they’ve released, on average, almost an album per year since their 1997 debut, and they count among their fans artists as diverse as Phil Lesh and Annie Clark (aka St. Vincent). This year, Eastwood Guitars is even producing a Deerhoof guitar model that was designed with the help of Rodriguez and Dieterich.

The San Francisco-based quartet’s 17th and latest release, The Magic, finds them tapping into their most avant-garde tendencies while still leaving room for rockist riffs and allowing Saunier’s love of the Rolling Stones to peek through. Right before they hit the road to play dates in the U.S. and Europe, we spoke to the band’s 6-string duo about their genesis as players, how they generate their unique tones, the upcoming Eastwood model, and playing in one of the most off-the-beaten-path venues one could imagine—the Geneva, Switzerland, facility that houses the world’s most powerful particle collider.

—John Dieterich

You both started out playing keyboards. When did you switch to guitar?

Ed Rodriguez: My dad was a great guitarist. We lived in Waukesha, Wisconsin, the home of Les Paul. I started out playing organ and wasn’t even thinking about guitar. One day, at 13, he signed me up for guitar lessons, took me to a pawnshop, and bought me a Japanese Les Paul copy for $50. I eventually stripped it, and the neck is twisted—but I still have it! I was hooked early. I decided I wanted to be Hendrix, so of course I needed a wah pedal. My dad bought me a Memphis Auto Wah, which, of course, is totally different, but I didn’t know at the time.

John Dieterich: From 4 to 8 years old, I played piano. My brother decided he wanted a bass for his 15th birthday. I was four years younger and wanted to do anything he did. I decided I wanted a guitar, so our parents rented us instruments. I got a Hondo Les Paul copy. I’m left-handed, so I was playing it upside down, while my brother was playing his the regular way, and I thought, “Oh, crap—I got the wrong kind!” It was really awkward at first, but now I can’t even attempt to play the other way.

When did you first hear music that made you want to become a lifer?

Rodriguez: I never dreamed of doing anything else—even as a little kid I was playing organ at nursing homes. When I started writing on guitar, my teachers told me that it sounded a lot like Robert Fripp. So I went and picked up a copy of [Fripp’s 1979 solo debut] Exposure. The first song on that record is kind of a joke. It’s just a basic 12-bar blues jam. I was like, “This is what they think I sound like? This sucks! This isn’t what I sound like at all!” I threw it in a drawer and about a year later I listened to the rest of the record and thought, “Holy shit—Fripp’s amazing!” Then I bought some King Crimson, and it was all King Crimson for me for years. When I was 15, I read an article on Derek Bailey called “The Godfather of Experimental Guitar,” so I looked him up. Then I learned about Sonny Sharrock.

Since Deerhoof band members live thousands of miles apart, their latest album, The Magic, was written by circulating MP3s from afar before meeting in the studio.

I got a John Cage book when I was 14 and it completely blew my mind, though I hadn’t heard his music. Then, when I was 16, I went to a performance of his “Child of Tree”—which was amplified plants. As in, mics ... attached to a guy ... touching plants. I was sitting in the auditorium thinking, “This fucking sucks so bad.” His actual music is great, but his concepts are what completely changed how I looked at things.

Dieterich: Same for me—I read Cage’s Silence: Lectures and Writings, his other books, and many interviews. I loved how he was always reiterating everything: He had his spiel, and you got pounded with it.

Rodriguez: Yeah, and all these quotes like, “Two people making the same music is one music too many.” He taught me that it’s better to do something nobody else is doing. I really connected with that.

Dieterich: At 11 or 12, I was very introverted about playing guitar—I didn’t want to share it. It wasn’t for other people. Eventually I started playing with my brother and his friends. I was hearing Black Flag for the first time, as well as whatever was on the radio. My first year of college, I joined the BMG music club and I picked music based on either the cover or the description. I ended up with things like Captain Beefheart and the CTI Sampler: Masters of the Guitar compilation. The last song on it was Mahavishnu’s “The Dance of Maya,” which was very Crimson-esque, and I first heard King Crimson around the same time. But I was also seeing bands like the Jesus Lizard. Shred music was everywhere, so it was really inspirational to see Duane Denison play ridiculously stiff, brittle, un-bluesy stuff. It wasn’t supposed to feel good. It wasn’t supposed to be emotional. It kind of made your skin crawl. That was the first time I saw a guitar player do that. In fact, the aspect of McLaughlin’s style that I like is that it can be stiff. They were two of my big influences.

Dieterich: If you want to talk about life-changing guitar players, for me, it was seeing Ed for the first time in his old band Behemoth.

Rodriguez: This was pre-internet days, so we didn’t know there was another Behemoth in Sweden [laughs].

Dieterich: We were both living in Minneapolis at the time. I went to a show, and it was the first time I’d ever heard music like that. Ed was instantly my new favorite guitar player. I was terrified, but I thought, “I have to meet these people because this is my only chance of getting to play music that I like.” We ended up playing together in Colossamite and Gorge Trio.

YouTube It

This December 2014 performance captures Deerhoof’s energy and unpredictability. There’s some Robert Fripp in John Dieterich’s opening riff, but by the two-minute mark it’s all about signal destruction, pealing harmonies, and sputtering chaos.

You two seem to have a brotherly connection. Is there ever a feeling of brotherly competition, too?

Dieterich: I was very intimidated by Ed for a long time. I think he was much further along in developing his playing style. Seeing Behemoth for the first time made me think about music in a different way, but I didn’t know how to approach it. I had been improvising, but I didn’t know that it was actually a thing people did outside of jamming in your room, by yourself. It was nice to finally meet people who were further down the path that I desperately wanted to be on.

Rodriguez: I felt inspired when we met. We started working on music together immediately. I heard a definite voice in John’s playing. It’s great when you find common ground with someone.

Dieterich: Especially when it’s something that’s not specific or something you can label—it’s a kind of aesthetic affinity that’s much deeper.

Rodriguez: Our sense of rhythm and how we look at tension and release are similar. It’s very natural for us to complement each other. We know how to stay out of each other’s way. It sort of gives the impression of one big guitar instead of two guitars. A very common thing when we’re playing live is, I’ll think, “Man, what I’m playing is really cool!” And then it’ll change, even though what I’m doing with my hands hasn’t, and I’ll realize it was John doing something really cool. I can’t even tell us apart a lot of the time!

John, these days you’re in Albuquerque, and Ed, you’re in Portland. Greg and Satomi are both in New York. So how does the writing process work?

Dieterich: We write separately, pass around MP3s, then meet to put it all together.

Rodriguez: The only consistent thing about Deerhoof is that there has been no writing system that has lured us into a comfortable space. Part of how we stay so interested is we constantly reevaluate everything. When we were writing The Magic, we didn’t really spend much time together. On some of our records I can’t tell you whether I played on a certain song or if John played all the parts. Greg’s guitar demos might end up on final mixes. We’re really good with making the best out of the situation we’re in. People are often shocked that we don’t live in the same city, but I feel like we barely skip a beat.

Although Deerhoof’s John Dieterich uses a variety of instruments, his mainstay is a 1961 Gibson Melody Maker.

Photo by Tim Bugbee: Tinnitis Photography

You spend a lot of time together on the road, so maybe that helps?

Rodriguez: Yeah, but we’d have these situations where we would go on tour for months, have a week break, come back, play, and it would feel like everything just disappeared.

Dieterich: Whatever was “there” wasn’t there anymore.

Rodriguez: We would have to dig a little bit to get it back, but now I feel like it’s just a small layer of dust, not six feet of dirt. You know, when bands live in the same city there are real challenges, too: There’s the one person who always cancels practice, or you all end up going to a bar or a movie, instead. But we’re actually going to New York to practice in a week and we’re not making plans with anybody else we know. We’re 100 percent there for the band. We’ll wake up, eat together, play, and enjoy it, because we miss each other and we know that it’s precious. Also, we’re a group of deadline-oriented people.

John, you usually play a Gibson Melody Maker, a guitar not commonly associated with intricate music. Do you have to fight with it a little?

Dieterich: I had never played an instrument that had that kind of neck and I just fell in love with it. I sat down and played it and was like, “This is what I’ve been looking for!” That said, our soundman has gear we use sometimes, and I’m fine with it. I feel a little sad saying this, but I don’t feel connected to a particular instrument. There are classical musicians who play a single instrument their entire lives. I admire that kind of intimacy. Greg makes fun of me because every guitar I play I’m like, “Wow—this thing’s awesome! This is the best guitar I’ve ever played!” I tend to do that with a lot of different things, like food and whatever [laughs].

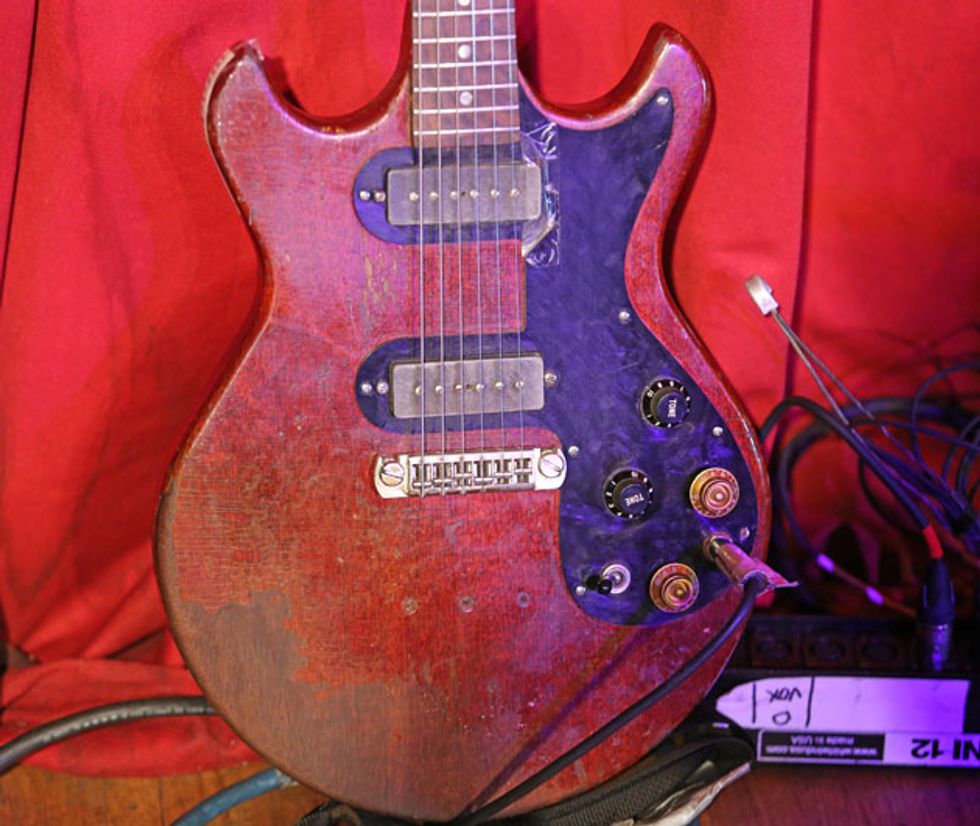

Ed, can you talk a bit about your trademark pink guitar?

Rodriguez: I put it together from parts—I had an idea and just went for it. I wanted a colored neck, so I got a Dean Custom Zone for $90 on eBay and took the neck off it. I reshaped and painted the headstock and put different tuners on it. The body is by SurfLeaf. I emailed them with specs and they made it for something like 80 bucks. The pickups are BG Pups. I spray-painted the covers. It’s got one 3-way switch and one volume knob. I like to keep things as simple as possible. It’s been smashed by the airlines more than once.

John, you often have a neck-pickup sound, but it’s also really bright. Are you actively using the tone and volume controls of your guitar or is that coming from somewhere else?

Dieterich: It’s coming from the amp, mostly. Dan Pearce made solid-state amps in the late ’80s. I got mine used in ’95 from some guy in Madison. It’s two channels at 100 watts, or you can bridge them for 200. It’s a really great amp. It has parametric mids. Its best feature is a presence knob. When I hear our old recordings, I’m a little bummed because I didn’t really know how to use the amp yet. I just made the most ear-crushing sound possible. What I’m going for now is a little more articulate and I can control it better.

Ed, what amp do you use?

Rodriguez: I just switched to a Quilter 101, which I love, but up until recently I’ve been touring with an Orange Tiny Terror.

Tiny Terrors are amazing, but don’t have much headroom. If you hit a boost, they don’t get louder, they just distort more. Was that a problem?

Rodriguez: It could be, at times. We’re very big on arranging, so if we have a moment where I might need to boost, the rest of the band will be quieter. We’re all about dynamics. We’re also really big on using whichever guitar setup will bring out a part the most. If I played a part on the record and I can’t cut through with my live setup, John may end up playing it—and vice versa. It was really eye-opening when John and I were first trying to figure out setups, by the way. We got a bunch of different cabinets and speakers, and swapped them around. I ended up with a 75-watt Carvin speaker in a Polytone cabinet. It sounds great.

You guys like to keep it compact. At one point weren’t you touring with ZT Lunchbox amps?

Dieterich: Yeah, we did at least one tour where I was. Were you doing it too, Ed?

Rodriguez: There was one tour where I was running a MIDI setup through the ZT, but I abandoned that MIDI thing. If anyone makes a tiny amp, there’s a pretty good chance we’ll end up trying it, though—another cubic foot of space in the minivan is always welcome!

Dieterich: We don’t really have a choice with our “business model.” We travel in a minivan, because it saves money. There’s the band, our sound person, and all of our gear, including our merch. It’s insane. It’s a jigsaw puzzle.

Rodriguez: We don’t want to pay for extra bags when we fly, so when we’re in Europe we’ll bring our heads and rent cabinets. A big part of us being able to operate with this as our livelihood is trying to save as much money as possible.

Do you normally play in standard tuning?

Rodriguez: Yes, I think it’s the most natural. It’s interesting to get what people may consider non-traditional sounds out of that tuning.

You both often explore dissonance. Is that a concerted effort or is that just where you go naturally?

Dieterich: I think it’s pretty natural.

Rodriguez: When I write for Deerhoof, I have to try really hard to make it less dissonant. My tendency is just stacked seconds—as dense and as clashing as possible. With that thought in mind, I’m always trying to space out the intervals.

Are there any “secret weapon” pedals on your boards?

Rodriguez: A simple one is we put our tuners last. We have so much stuff in our music where we need to stop on a dime, so we use our tuners as a total mute. We’ll have huge feedback or a super-loud part, and then we can just cut it clean.

Dieterich: The EarthQuaker Bit Commander. Since it’s also going DI, I can get into really huge synth-bass stuff. At least two people a night ask, “How the hell did you do that?” I’ve probably sold 100 of them [laughs]—seriously! Sometimes I’ll add another pedal to my board, like an Octavia [by Roger Mayer], just for feedback. I used to do that with a [Crowther Audio] Hotcake, but I’ve broken a few over the years.

Rodriguez: I always use an Octavia for my distortion. A few weeks ago I met with the people at Catalinbread, which is based in Portland, where I live. I really like their Octapussy octave fuzz.When I roll off the low end, it’s like a perfect bright synth, and when I roll the bass up it turns into psych-like fat buzz.I missed the whole boutique pedal explosion, mainly because I’ve always been broke. For so many years the prices weren’t that competitive. I thought, “Either I can get this Boss distortion for, like, $90 or buy this other one for $400.” Of course, I’d always prefer to have something custom, but I couldn’t afford that. Now it’s great that the cost gap has really narrowed.

Rodriguez, shown here onstage with a prototype of the band’s Eastwood signature guitar, reveals a simple pedalboard trick that serves the band well: “We put our tuners last. We have so much stuff in our music where we need to stop on a dime, so we use our tuners as a total mute.” Photo by Zane Roessell

How did you end up partnering with Eastwood?

Rodriguez: We’ve had offers from boutique guitar companies, but I could never afford those instruments without an endorsement. I don’t know if I have this kind of sway with anybody, but if I do then I don’t want to motivate some kid to save up $2,500 to buy a guitar when I’ve never paid more than $450 for one. We met Mike from Eastwood when we played at the All Tomorrow’s Parties in New York around 2009. He sent me the [Airline] Tuxedo, John got a Classic 12, and Satomi got one of the basses. I played that Tuxedo forever and completely loved it. After that tour, I continued playing it, because it just worked with everything.

When the La Isla Bonita tour started, I built the pink guitar because I wanted to have a whole new vibe going. Mike sent an email asking why I dropped the Eastwood. I told him I like to switch things up every once in a while, especially for a new record. He said he’d love to see us playing Eastwoods again, and offered to make a Deerhoof guitar. He suggested using one of their existing guitars as a starting point. I was looking through the models that he had, and noticed the Ampeg “scroll” bass. I asked him, “Is it possible to make a guitar on that body, because that would be fucking badass.” He thought it was a great idea, and their designers drew out the plans. Initially the wiring was different, but then we got the idea for a bass roll-off. A lot of the times when we do backline, one of our issues is there’s too much low end in those big cabinets. We used to bring EQ pedals to try to clear up some of that mud.

Dieterich: The pickup options are great, too. When we’re touring, about half of the venues have bad electricity. So you basically can’t use single-coils. It’s really useful that this guitar can be used in single-coil mode, where the pickups sound killer, but in humbucker mode they still sound really good and they’re completely noiseless.

There are some pretty unconventional guitar sounds on The Magic that seem to be the product of studio decisions. Are there any you’re particularly proud of?

Dieterich: I like the guitars on “Model Behavior” a lot. It’s a very thin, out-of-phase sound from a homemade guitar I made from Sonex parts [from the short-lived 1980s Gibson budget line]. I ran it through a DI into an old tube preamp, with no additional EQ, compression, or anything. The pickups were made by Aron Sanchez at Polyphonic Workshop, who is amazing and plays in a great band called Buke and Gase. They’re very hi-fi sounding, full-frequency, under-wound pickups.

How did you guys end up playing amidst the machinery at the Large Hadron Super Collider in Switzerland last year?

Dieterich: It was just weird fate. Greg has another band with our soundperson, Deron Pulley, and they were playing a show in New York. After it, I was talking to this physicist, James Beacham, and he said, “I have this dream of bringing Deerhoof to the Large Hadron Collider where I do work.” I was like, “Okay, amazing.” I never actually expected it to happen, but then he got in touch! It was this incredibly unlikely thing that nobody believed was going to happen ... until the day it did.

Deerhoof's Gearbox

John Dieterich’s Gear

1961 Gibson Melody Maker

Pearce G2r solid-state head

John's pedalboard includes: Fairfield Circuitry Barbershop Millennium Overdrive, Shoe Savior Machine, DOD/Shoe Looking Glass overdrive, EarthQuaker Devices Bit Commander, EarthQuaker Devices Disaster Transport Sr., and a TC Electronic PolyTune 2 Mini. His accessories include: .011–.050 string sets (various brands), Dunlop Max-Grip .88 mm picks, and a Boss TU-3 tuner

Ed Rodriguez’s Gear

Ed's Eastwood EEG Deerhoof prototype (shown above) and a Custom Dean/SurfLeaf parts guitar

Quilter 101 Mini Head going into a 1x12 Polytone cabinet with 75-watt Carvin speaker

Ed's board includes a Catalinbread Naga Viper, a Catalinbread Octapussy, and a Catalinbread Belle Epoc. His accessories: .010–.046 string sets (various brands), Dunlop Jazz III picks, a Boss TU-3 tuner,

and a Cioks DC5 power supply

And if you want to learn even more about their gear or hit all in action, watch our Rig Rundown with John and Ed:

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)