There's no more biblical—New Testament, of course—introduction to the raucous, bouncing, mesmeric sound of North Mississippi hill country blues than the new Black Keys album, Delta Kream. It's essentially the agrestic subgenre's greatest hits: a collection of ripe corpuscles from the catalogs of R.L. Burnside, Junior Kimbrough, Ranie Burnette, Big Joe Williams, and Fred McDowell, plucked straight from the music's thumping heart—as chiseled into its core DNA as the faces of Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt, and Lincoln are into the granite of Mt. Rushmore.

Burnside and Kimbrough, in particular, are the album's marrow, and that's a matter of faith. "People might not have heard of them, but they are two of the most important American musicians that ever were," preaches Dan Auerbach, the guitarist and singer who, along with Patrick Carney, breathes life into the Black Keys. "Pat and I are doing this entire thing in honor of them."

The Black Keys' "Crawling Kingsnake"

Watch the Delta Kream crew—Dan Auerbach and Pat Carney of the Black Keys amended by guitarist Kenny Brown, bassist Eric Deaton, and percussionist Sam Bacco—play Junior Kimbrough's version of John Lee Hooker's "Crawling Kingsnake." Auerbach plays his 1960 Tele Deluxe and Brown is on his 1958 Silvertone. The primary location is the Blue Front Café in Bentonia, Mississippi—the longest continuously operating juke joint in the United States. Its proprietor, Jimmy "Duck" Holmes, for whom Auerbach produced a Grammy-nominated album, makes a cameo at 2:10.

And so a band that worked its way up from dive bars to headlining arenas, outdoor sheds, and festivals over 20 years—along the path distilling and evolving their original garage/blues sound into a brilliantly crafted, writerly, and eclectically influenced approach that's magnetized multiple Grammy nominations and hordes of fans, plus yielded 10 studio albums—does a musical 180. The smooth-but-sassy hooks inside albums like Brothers, El Camino, and Turn Blue—their platinum-selling trilogy from 2010 to 2014—are replaced by the rough-hewn, barbed ones of "Coal Black Mattie," "Poor Boy a Long Way From Home," and "Stay All Night." And nods to funk, psychedelia, pop, rockabilly, surf, and other normative forms are replaced by a devotion to a sound that echoes up from the African diaspora.

"In R.L. [Burnside], I could hear the ghosts of the whole lineage of the music that comes up the Mississippi River combined with all the cool bar sounds I loved about Chicago blues, all rolled into one person." —Dan Auerbach

That the call and response of Senegambian village drummers, the drone of the 1-stringed njarka, and the keening trill of handcarved reed fifes would still resonate so distinctly in a strain of rural electric blues might be called a near-miracle, if not for the dark cloud of their origins. As musicologist Edward M. Komara explained to me one night over copious beer and whiskey in a bar in Oxford, Mississippi, his extensive research shows that North Mississippi's slave owners were more tolerant of the indigenous music of their human property than those of the Delta and most other parts of the deep South, where drums and traditional rhythms, especially, were feared to be signals of rebellion. As a result, even today the Rising Star Fife and Drum Band plies grooves forged in the Niger Delta, and the one-chord stomp perfected by the late Kimbrough and Burnside stands as a nexus between the sounds of world music, psychedelia, rock, folk, and anything else that came into its octopus-like grasp over the past 400 years—amplified loud.

"The first time I heard the North Mississippi sound was in Alan Lomax's field recordings and Fred McDowell's Arhoolie label recordings," Auerbach recalls. "I fell in love with that stuff, and Fred's 'Write Me a Few of Your Lines' became a favorite song. With this stuff, some people get it, some people don't. When I first heard Junior Kimbrough"—whose melismatic singing and greased-spider guitar lines are a form of sonic hypnotherapy—"I didn't get it. It was way easier for me to get into R.L. Burnside. I had both of their albums, on Fat Possum, and in R.L. I could hear the ghosts of the whole lineage of the music that comes up the Mississippi River combined with all the cool bar sounds I loved about Chicago blues, all rolled into one person. And at the Euclid Tavern in Cleveland, I got to witness R.L. destroying a crowd. It was a combination of those records and seeing those guys play live, which was so intense it was mind blowing."

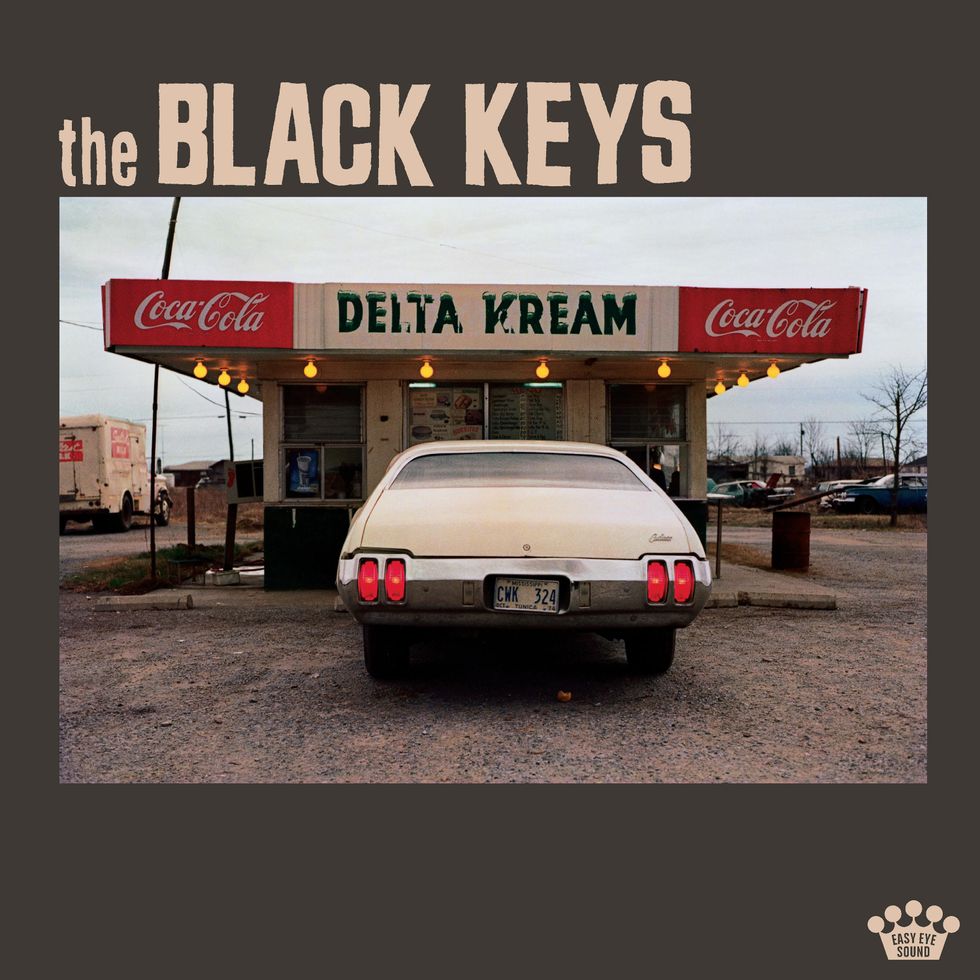

TIDBIT: The cover of the Black Keys' new album is a photo by William Eggleston, who in the 1950s began capturing Southern life. It was taken at a snack bar in North Mississippi.

By the time Auerbach and Carney, who've been playing together since they were 16 and 17, determined to make the Black Keys' 2002 debut, The Big Come Up, the sound of other raging Mississippi jukers like Paul "Wine" Jones and T-Model Ford was also in their gullets.

The Black Keys have paid homage before, with 2006's Chulahoma: The Songs of Junior Kimbrough. "I think we tried some of the songs we recorded for Delta Kream on those sessions, but it just didn't work out," Auerbach offers. "I'm not sure that, even 10 years ago, we would have been able to play these songs correctly, but Pat and I have both grown as musicians, and Pat's drumming blows me away on this album. It's so on the money and so him at the same time."

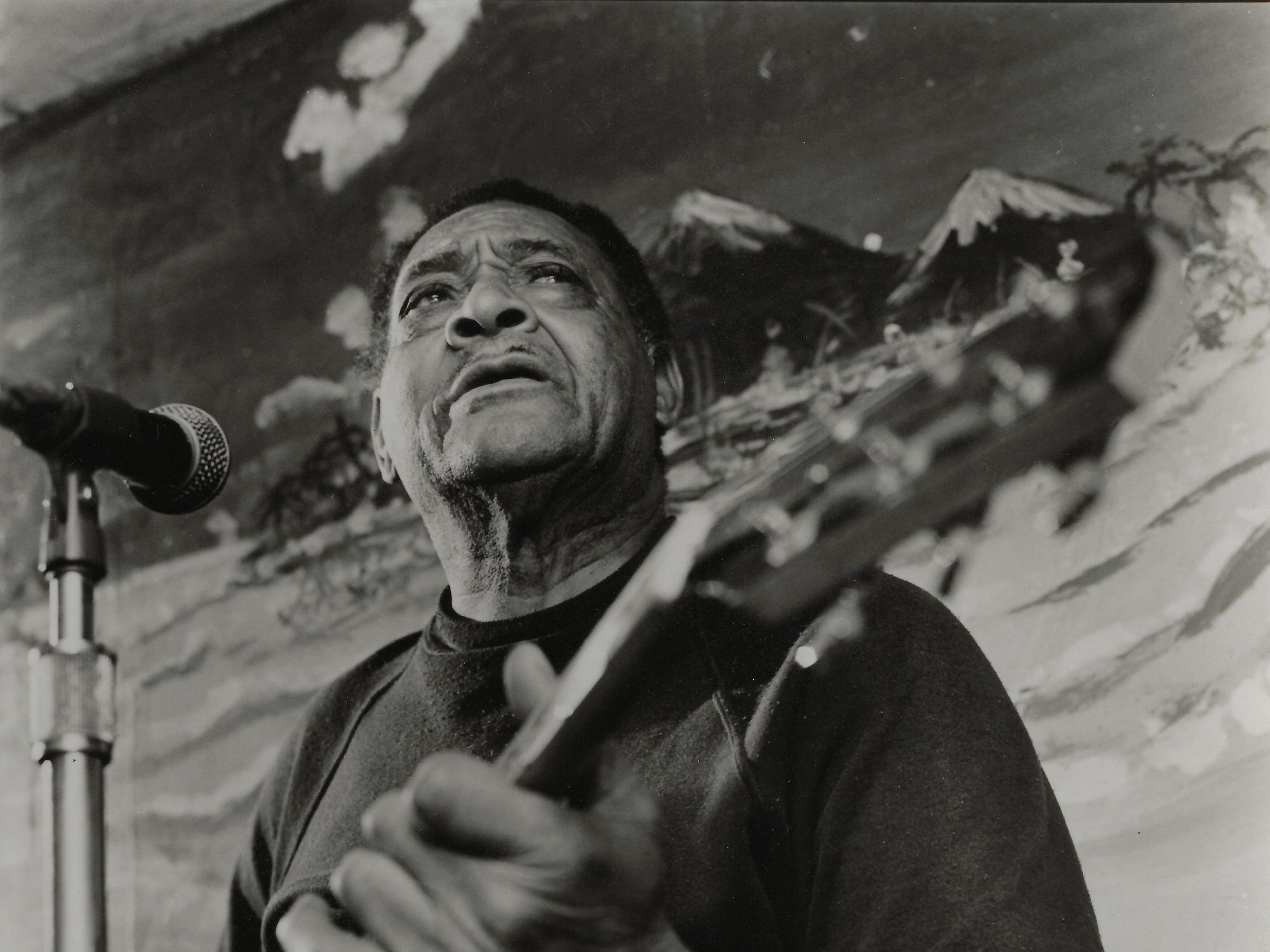

Junior Kimbrough holds court from the stage of his juke joint in Holly Springs, Mississippi, in 1995.

As Auerbach's solo albums and productions for artists as diverse as the Pretenders and 73-year-old bluesman Jimmy "Duck" Holmes have shown, he's also developed a knack for assembling the right cast of musicians. And for Delta Kream, he invited guitarist Kenny Brown, who played with Burnside for decades and earned the old wizard's praise as his "adopted son," and Eric Deaton, an MVP among hill country and Delta bandleaders, to help make the album bone-true. Percussionist Sam Bacco, another of Auerbach's frequent accomplices, completes the krewe.

"What some people miss about this music is that the right-hand technique is what really makes it." —Kenny Brown

Honestly, they were already at Auerbach's Easy Eye Sound Studio in Nashville, where they'd been pressed into service for Sharecropper's Son, an album Auerbach produced for Robert Finley. "When we finished the session for Robert's record, I texted Pat and told him he should come over the next day, just because it was so much fun to play with Kenny Brown. And that was pretty much it. It was a bunch of first takes. Two days later we had an album. We played all these songs we loved, from memory, and having Eric there to help me was great, because he knows all that stuff cold. And Kenny played on all of the original recordings! If you're a lover of hill country records, you love Kenny Brown even if you don't know it. I didn't fully realize it until he was sitting next to me, playing. It was that sound—the slide, those heavy notes. That great sound on 'Sad Days, Lovely Nights,' where he just hangs on the slide and makes this atmospheric sound.… He did that behind Junior Kimbrough on the original recording. That's my favorite musical moment from one of my favorite records—and there it was."

Kenny Brown, left, with his twice-stolen-and-returned 1958 Silvertone, added authentic blood to the Delta Kream sessions at Auerbach's Easy Eye Sound Studio. This master of Mississippi hill country guitar initially learned from the legendary Joe Callicott, Brown's neighbor as a child, and then apprenticed under the decades-long guidance of R.L. Burnside.

Photo by Alysse Gafkjen

Brown first met Auerbach over a decade ago at Norway's Notodden Blues Festival, on an artist shuttle heading back to the airport. "We had all had a late night and nobody was talking much," he says. But at the Delta Kream sessions, they instantly spoke the same musical language. "Dan is great to play with," Brown notes. "I loved the studio because it had great gear and Dan got really good sounds quick, and he's like me: He doesn't really play anything exactly the same way twice, so it always feels real fresh.

"Man, doing these songs bought back all kinds of memories. I was thinking about how we played 'Crawling Kingsnake' on Junior's first album, that we cut at his juke joint. And playing 'Poor Boy a Long Way From Home.' After 40 years, at least I can do 'em good now," Brown says, laughing.

"What some people miss about this music," says Brown, "is that the right-hand technique is what really makes it. A lot of the songs R.L. did, you can play with one finger on your left hand, but the right hand takes about three fingers working really fast. To really get the sound, sometimes you need to hit the strings, like a percussion thing. I think that comes from the fife and drum music. I do a lot of muting with my left hand and the heel of my right hand, and even the bass of my thumb. I don't even really think about it anymore, unless I try to teach somebody how to do it."

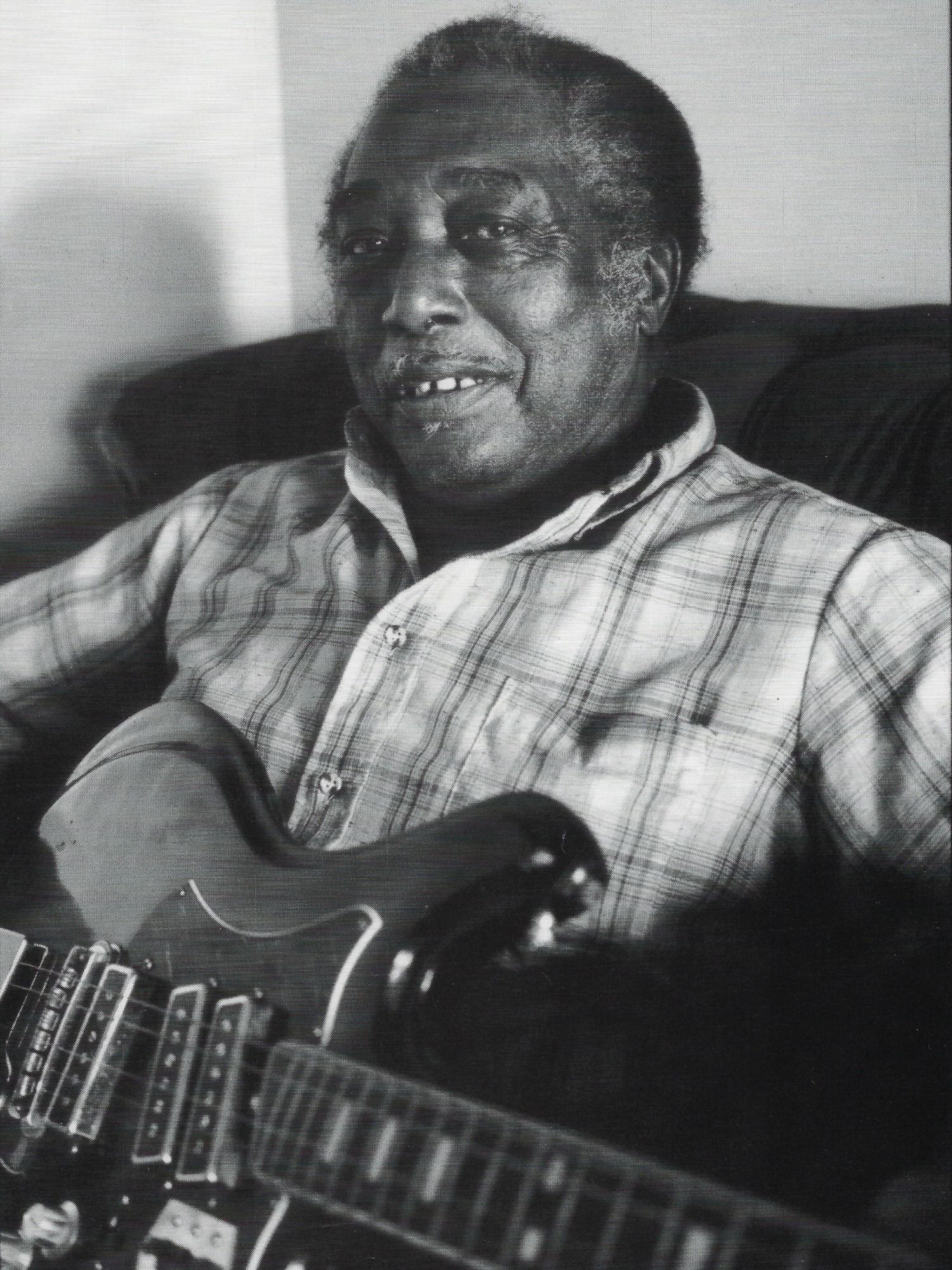

R.L. Burnside cradles an old Teisco in this 1996 publicity photo, but he was never fussy about what guitar he played.

For the sessions, Brown brought his beloved 1958 Silvertone. The guitar's been stolen from him twice, and returned, largely because it's recognizable by the twin popsicle sticks behind the headstock used to raise and anchor the tuning pegs. He also brought along the 1989 made-in-Mexico Stratocaster he frequently wielded with Burnside. And he used a third guitar: Fred McDowell's familiar Gibson Trini Lopez model, which Auerbach now owns along with Hound Dog Taylor's Kawai Kingston (a model often referred to generically as a Teisco, one of Kawai's popular spin-off brands), which also dishes out dirt on Delta Kream. Brown used only one pedal—Auerbach's Basic Audio Scarab Deluxe Fuzz, which he admired enough that the Black Key sent him one after the sessions.

Besides Hound Dog's Kawai, Auerbach played his beloved 1960 Telecaster Deluxe, which, he notes with a laugh, Nashville session legend Tom Bukovac has dubbed "the finest Tele on Earth." He enjoyed pairing it with an Analog Man Sun Face. "I used it a lot and kept it on with the volume down for my clean sound. The Tele pickups really work well with it. And the B-string on my Tele buzzes a little, because of the action, and I really like that. I told my guitar tech to leave it, because it always has a little sitar thing. You can hear it on the album."

"When I was 18, I label-maker-ed my name on the headstock of one of my Teiscos because of Hound Dog Taylor." —Dan Auerbach

DAN AUERBACH'S GEAR

Guitars

- 1960 Fender Telecaster Deluxe

- 1960s Kawai Kingston S4T formerly owned by Hound Dog Taylor

- 1960s Gibson Trini Lopez Standard (played on the sessions by Kenny Brown and formerly owned by Fred McDowell)

Amps

- 1950s Fender narrow-panel tweed Deluxe

Effects

- Ebo Customs E-Verb

- Analog Man Sun Face

Strings & Picks

- SIT .011 sets

- Jim Dunlop Custom picks

Auerbach acquired the Kawai through Bruce Iglauer of Alligator Records, the label Iglauer founded in 1971 to put out Hound Dog Taylor's debut album. "That was really gracious of him, and I've been using it non-stop ever since I got it," Auerbach attests. "We didn't do anything but clean up the pots, and it sounds and works great. It still has Hound Dog's name on a strip from a plastic label maker on the headstock. When I was 18, I label-maker-ed my name on the headstock of one of my Teiscos because of Hound Dog."

His amp of choice was a vintage, narrow-panel tweed Fender Deluxe paired with an Ebo Customs E-Verb. "I set the reverb right next to me when I played so I could turn it up and down in the middle of songs, for solos," he adds. Since the original versions of all the numbers on Delta Kream were recorded by players who eschewed picks for fingers, it seemed natural to ask Auerbach if he followed suit. "I did both. Junior and R.L. never used a pick, but once in a while I indulged myself," he said, chuckling.

"There's no set pattern to how we record or plan an album," he says. "Every one's been pretty different, and we never talk about it ahead of time—never. It's just fun and spontaneous, and sometimes those moments and ideas end up being the most pivotal."

Put Dirt in Your Ears

Fuel up on the North Mississippi hill country blues sounds that inspired the Black Keys' Delta Kream.

Too Bad Jim, R.L. Burnside: Burnside's debut album on Mississippi's Fat Possum label is a rough-hewn testimonial to the rugged, ragged power of this regional folk-art form. With Burnside and Kenny Brown on slide, rhythm, and lead guitars, this set was a major influence on Auerbach and Carney during the Black Keys' formative years.

All Night Long, Junior Kimbrough: From the first notes, Kimbrough's idiosyncratic approach to blues is obvious and mesmerizing. Listening carefully, you can hear the threads of African music, hardcore blues, psychedelia, improvisation, and primal rock pulling together in his rather eerie sound.

You Gotta Move, Mississippi Fred McDowell: The rural majesty of McDowell's rhythm 'n' slide style is instantly arresting. No wonder he became a popular opener for major rock bands from the late 1960s till his death in 1971. You know McDowell's "You Gotta Move" from the Rolling Stones' version, and here you can enjoy the original "Louise," which the Black Keys recorded for Delta Kream.

Everybody Hollerin' Goat, Otha Turner and the Rising Star Fife & Drum Band: Get down to the roots of the hill country sound with this album of the straight-from-Africa echoes of Mississippi fife-and-drum music. Turner, who carved his own reed fifes with heated metal rods, died at age 95 in 2007, but his granddaughter, Shardé Thomas, still leads the band today.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)