So, what led to The Black Keys ending their unannounced hiatus? Well, for Auerbach, it was the same guitar that started the ascent up this crazy rollercoaster—Glenn Schwartz’s 10-string hollowbody. James Gang and Eagles ace Joe Walsh was jamming with Auerbach at Easy Eye and the two brought up Schwartz and how his ferocious playing impacted them both. Auerbach spent any free time he had during high school to make the trek from Akron to Cleveland to see Schwartz play. Walsh coincidentally looked to Glenn as a guitar hero and eventually took over for him in the James Gang when Schwartz left the band, moved to California, and formed Pacific Gas & Electric. (You can see the trio of guitarists jam at Nashville’s famed Robert’s back in 2016.)

Auerbach and Walsh got Schwartz down to Nashville to record him at Easy Eye Sound Studio. The session was inspiring and provided Auerbach the visceral memory of why he loved the Black Keys. The next day he called Carney, they put a session on the books and Let’s Rock was made.

Premier Guitar made the comfortable drive south to Atlanta’s State Farm Arena to not only check in with Auerbach’s longtime tech Dan Johnson, but the guitar master himself makes a cameo to talk all things guitar, including Glenn’s aforementioned 10-string that was loaned to him after a recent Cleveland gig. Other 6-string highlights include a gold-foil-loaded Peavey Razer gunning for the T-Model Ford mojo, a lawsuit-era Ibanez SG, a custom-build (by Dan Johnson) that echoes back to industry heavyweight Paul Bigsby, and surprisingly enough, a ’59 burst. While there, we also spoke with new bandmembers Delicate Steve, and the Gabbard brothers (Andy — above left — and Zach who are also 2/3 of the Buffalo Killers) from Akron, who all show off the goodies they bring to the arenas to back their longtime buds.

Here’s the 10-string that was used and abused by one of Auerbach’s guitar heroes, Glenn Schwartz. Some notable things Glenn did to this instrument are the extended f-holes, swapped in the solid-brass tailpiece that goes through the whole guitar, and because Glenn was very religious, he believed that if you played music for the Lord, you played a 10-string instrument, so he added the four strings to the lower bout. All of Auerbach’s instruments take SIT .011–.050 strings.

Inspired by Mississippi juke-joint legend T-Model Ford, aka James Lewis Carter Ford, Auerbach tracked down this Peavey Razer. The homage is complete with the “T Model The Taledragger” stickers that were on Ford’s beloved Razer. The electronics have been upgraded and the stock pickups have been substituted with DeArmond gold-foils from a Harmony. The tailpiece is from a Kay and tech Dan Johnson machined the bridge and vibrato arm from brass.

Here is one from the old days—a lawsuit-era Ibanez modeled after a 1961 Les Paul Custom aka the first SG.

“I gotta admit, I got this guitar because of these absurd furniture nails,” admits Dan Auerbach. This lawsuit guitar was upgraded with Lollar Lollartrons and an old Bigsby off his Gretsch Duo Jet. Dan Johnson believes this came from one of Neil Young’s guitars as the vibrato was a gift from longtime Young tech Larry Cragg. Ironically, after purchasing the guitar and sitting with it in his living room, he realized it’s the same lawsuit guitar on Junior Kimbrough’s All Night Long, which was a major influence. Billy Sanford, the guitar man behind the “Oh, Pretty Woman” lick, coined the guitar “Nails in My Coffin” because of the guitar body’s rivets the nameplate on the nut cover. Perfect!

It’s no shock to any guitar dork that Auerbach is attracted to odd-shaped instruments. A Gretsch employee reached out to Dan Johnson and wanted to send Auerbach a G6138 Bo Diddley Firebird. The band received it while rehearsing for the Let’s Rock tour at the Wiltern in Los Angeles. The Dans agreed that the guitar needed to be stripped of its red top, so Johnson got to work. Once it was removed, they wanted to stain it like a piece of furniture from the ’70s, but it was late and Johnson didn’t think he could find a hardware store open around midnight. Lucky enough, a Wiltern maintenance worker knew where in the basement he could find the necessary woodworking supplies. Beer in hand, Johnson stained the guitar and let it dry overnight.

Here is a copy of a copy of a copy. Let us a explain. The Italian brand Eko made a signature guitar in the mid-’60s for their version of the Beatles, the Rokes. (Think along the lines of Mosrite building Ventures models coinciding with the surf-rock juggernauts.) Then the Japanese company Kawai made a copy of that in the late ’60s and it was nicknamed the “Flying Wedge.” And as Auerbach does, he bought a Kawai model on eBay and it was shipped directly to Johnson. It was cheap. It was horrible. It wasn’t playable. So, to make good on the bad bargain, Johnson started his own flying-wedge project. It incorporates flavors from its misfit predecessors including Lonnie-Mack’s-Bigsby-Flying-V workaround and machined parts reminiscent of Paul Bigsby’s early work. It has a chambered bird’s-eye maple body and Firebird-style mini-humbuckers. The project was finished just before the Atlanta show on November 9th and played onstage for the first time that same night.

This is a one-owner 1959 Gibson Les Paul that Dan Auerbach bought this year. He’s already recorded with it at Easy Eye and has truly enjoyed owning it. While he admits that a ’59 ’burst isn’t a guitar you’d attach to him because so many other famous guitarists have forged history with it, he couldn’t turn down the opportunity to have such an inspiring instrument. “I had no intention of buying a ’burst,” says Auerbach. “I’ve never even seen one before I walked into that guitar store and bought it from the owner’s sister.”

No, you’re not looking at a Stonehenge-sized Tetris wall, it’s Auerbach’s current lineup of amps.

While doing tour rehearsals at Easy Eye, they were going through the gear vault and brought out the usual suspects—The Marshall, the Danelectros, the Fender Quads. But something was lacking, so the Dans headed down to Nashville’s Carter Vintage and scored two early ’70s silverface Fender Bandmaster Reverb TFL5005D heads (shown above). They were keen on getting a fresh Fender wrinkle because Auerbach needed the squishier punch you get from a tube rectifier. The other one tours alongside its brother and stays in the wings as a backup.

As seen in the 2012 and 2014 Rig Rundowns, a big part of Auerbach’s tone was provided by this Fender Quad Reverb platform. (Again, a nod to Ohio hero Glenn Schwartz who used two of these beasts onstage.) Now the Quads are extension cabs for the Bandmaster Reverb head and are loaded with 12" Tubby Tone Alnico 25-watt Hempcone speakers.

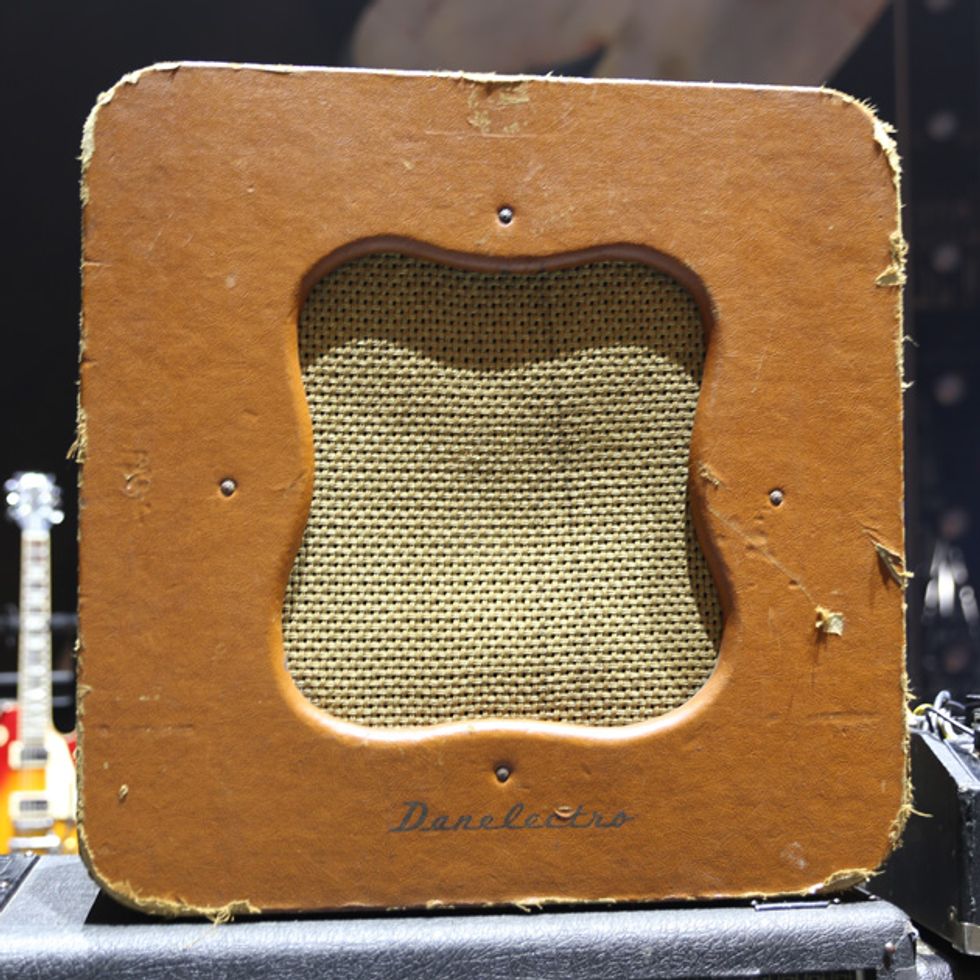

While Auerbach did have a 40-watt Danelectro Challenger in his last Rundown (1956 model), he now travels with two different ones from 1949 and 1950. It does have a 15" speaker in it, but the 1950’s speaker is bypassed and feeds into both the Marshall 8x10s. The 1949 Challenger goes direct to FOH for clean baseline tone.

Here’s the backside of this gem.

While the Bandmaster Reverb does have some ’verb dialed into its sound, the bulk of the dark, deep, lush, springy goodness you hear is from the Premier Reverberation unit that’s coupled with a Maestro Echoplex EP-4 for space-rock guitar solos.

The Canadian company helped BTO’s Randy Bachman after he unsuccessfully ran a Fender Champ into his Marshall head. It probably sounded uh-mazing before the combo was fried. So the Garnet H-Zog was invented to allow Bachman to run a lower-powered tube head, as a preamp, before his full stack. Auerbach adopted the approach and uses the no-load tube preamp in front of all his amps. The H-Zog itself is a tube amp with a single 12AX7 and a single 6V6 powering it.

Steve Marion aka Delicate Steve uses this 1966 Melody Maker SG a lot playing behind the Black Keys. In a 2019 interview with PG, he had this to say about it, “The guitar I played on the whole record [Till I Burn Up] was sold to me by my friend, a guitarist named Ofir Ganon, who is the only guitar snob-gear guy whose opinion I care about at all. Ofir sold me a ’66 Gibson Melody Maker SG, which had PAFs in it. The whole album is that guitar.” Steve normally plays .009s because he likes how they’re harder to control and the subtly of strings moving around, but he went with .010s to have more consistent sound for the Keys gig.

On previous Delicate Steve projects before 2019’ Till I Burn Up, Marion used an Epiphone Ltd. Ed. Joe Bonamassa 1958 “Amos” Korina Flying-V. He was gifted this Gibson Custom Shop Flying V VOS from the historic company before embarking on the Let’s Rock tour. It is all original and comes loaded with Custom Buckers.

Appropriately, Steve Marion uses this 2015 Gibson Firebird on the new Let’s Rock song “Eagle Birds.”

Definitely the most Black-Keys-ish of Steve Marion’s arsenal, this 1960 Silvertone Jupiter 1423 sees stage time for songs like “Tighten Up” and “Thickfreakness.”

The only request that Dan Auerbach gave the rest of the bandmates was to try and work with the Fender Super Reverb. (More of a suggestion than demand.) Delicate Steve has enjoyed his time with the Supers because they’re very different than his typical setup. In Delicate Steve he uses an Orange Micro Terror that provides a squashed, overloaded, overdriven sound whereas the Super he uses with the Keys offers the neutral pedal platform that needs to cover all the synth and keyboards with his guitar.

A part of his solo setup that’s crept in the Keys show is this custom-built HammerTone head that is chasing the sound of an old tweed Gibson GA-5 Skylark combo. Dan Johnson suggested that Marion run the head through a Palmer PGA-4 speaker simulator/load box and into the Fender Deluxe Reverb’s speaker.

To replicate all the synth, keys, and organ tones heard on the Keys’ albums Brothers, El Camino, and Turn Blue, Steve Marion travels with a hefty board of goodies starting with the Auerbach-favorite Electro-Harmonix Russian-font Big Muff. The rest of the stomp station has an MXR Carbon Copy Deluxe, Xotic EP Booster, JHS Colour Box, EHX C9 and Pitch Fork, Boss TR-2 Tremolo, ZVEX Mastotron, Valeton Coral Mod (a Delicate Steve fave), Pigtronix Octavia, and a Styrmon BigSky. Everything is harnessed by the RJM Mastermind PBC/10 loop controller.

Zach Gabbard and his brother Andy have a longtime connection with the Keys. They were at the band’s first show in Akron and their band Buffalo Killers’ second LP Let It Ride was produced by Auerbach. Coming full circle, Zach was recruited to play bass and sing background vocals on the Let’s Rock tour. Zach’s No. 1 is this Gibson SG Standard Bass—his first short-scale instrument and he absolutely loves it: “I’ve been working too hard for to long [laughs].” It’s a completely stock 2019 model and is strung up with flatwounds.

For this gig, Zach Gabbard moves the Earth with an all-tube Ampeg SVT-VR 300-watt head that powers a matching 8x10 cab.

In addition to running through his cabs, Zach Gabbard uses a Palmer PDI-CTC to provide FOH a clean, pure signal from the Ampeg SVT-VR.

At Zach Gabbard’s feet rest two pedals—an old EarthQuaker Devices Monarch fuzz and a Boss TU-3 Chromatic Tuner keeping his notes in check.

“This is my favorite guitar I own because it’s the best feeling guitar I’ve ever played,” declares Andy Gabbard on his Gibson Les Paul. He safely added the Bigsby via a non-invasive Vibramate, but the rest of the guitar is stock. Gabbard sees his role in the current three-guitar attack is to trust his feeling, following the duo, and accent everything that Dan is doing.

Another guitar, another Gibson for Andy Gabbard. This 2019 Firebird was a pre-tour gift from Gibson. Andy digs it because “it looks cool and it cuts through.”

“This is the guitar I’ve always wanted,” admits Andy Gabbard. This Gibson Les Paul Standard '50s P-90 Gold Top. Gabbard remarks that he had to put a Bigsby on their because his picking hand while hit the strings and then phantom shake because he’s so used to the vibrato arm being used.

For Andy, it doesn’t get any better than Gibson guitars into a Fender amp, and the combo in this equation is a Super Reverb.

An MXR Brown Acid Fuzz, Pigtronix Gate Keeper Micro, and EarthQuaker Devices Dispatch Master are the few stomps help Andy Gabbard get the job done.

Click below to listen wherever you get your podcasts:

|  |

|  |

D'Addario XT Strings: https://www.daddario.com/XTRR