While studying jazz performance at Berklee Global Jazz Institute, Moser was mentored by musicians such as Danilo Pérez, John Patitucci, and Victor Wooten.

Ciara Moser’s debut album Blind. So What? takes listeners deep into her brilliant, adventurous bass playing—and her life as a blind person in a sighted world.

Ciara Moser has a mission with her debut album, Blind. So what? The jazz-fusion bassist and composer is educating the sighted listener through her lyrics on the record, addressing a range of topics she has experienced and navigated throughout her 27 years, from spatial orientation and heightened senses to questions raised and misconceptions held about life as a blind person.

Blind. So What? was created as part of her master’s of jazz performance program at Boston’s Berklee Global Jazz Institute, where she was mentored by such esteemed musicians as Danilo Pérez, John Patitucci, Joe Lovano, and Victor Wooten. Her 6-string Fodera Emperor 6 Standard can be heard all over the record, and the title concept is front and center in the lyrics. Each song addresses a specific topic—and Moser does not mince words.

“The goal or the achievement that I’m looking for is to call for more awareness of blind people, and also, generally, for people with disabilities,” Moser says. “For me, some significant things about myself are the music that I play and being blind. It was always the question: How can I combine that? Why don’t I use my music to change what I want to change about inclusion and blindness? The Global Jazz Institute gave me the tools to actually do that through my music, because I could never connect those two elements 100 percent. Of course, I knew I already did that, standing out there publicly as a blind musician, but actually addressing the topic and writing an album about it is even more important, in my opinion.”

Ciara Moser - "Developing Senses"

Co-produced by Moser and Warren Petty, Blind. So What? begins with a cacophonous 38-second handshake, “Intro (Screen Reader),” where the words “blind, so what?” are read by computer software in 16 different languages. In the liner notes, Moser explains that it “should attract the listeners’ attention to the audible world a blind person lives in, and open up new ways of perceiving and listening.” Then, she gets into some real talk on the rest of the album, a modern jazz collection which fluidly dips and dives into funk, R&B, ambient, Latin, experimental, and, in one song, a kind of South Indian Carnatic vocal scatting called “konnakol.”

“Some significant things about myself are the music that I play and being blind. It was always the question: How can I combine that?”

Moser doesn’t sing lead on any of the songs (although she does some spoken word, including the album’s improvised finale, “The Lady with a Green Cane,” a poem by Fran Gardner). She hands that task over to best friend and fellow Berklee student Aditi Malhotra on a half-dozen songs, while Nishant Shekar, another close friend and member of the Berklee Indian Ensemble, sings the first single, the funky, R&B-tinged jazz number “I Trust,” which begins with this instruction of sorts: “Imagine how it is to live in a world that you can’t see / Relying on someone else’s helping hand, following every step, every turn, every move that’s made / Trust in your friends and family.”

But what follows is even more direct. “Disability is a stamp they put on us / I am a person like you / But you still treat me like I’m some kind of different thing,” Moser writes for the song “Different Ability, Pt. 1.” In the percussive “Memory,” for which she won a 2023 Herb Alpert Young Jazz Composers award, Moser explains her musical process: “I am memorizing every bit and piece of each song / For playing everything with discipline, concentration / I save it to my hard drive and use my memory to find the way through all the pieces I play.” That’s the actual lyric.

On her debut record Blind. So What?, virtuoso Ciara Moser dazzles with spectacular bass performances and striking lyrics about her life experience.

It’s an atypical approach to songwriting, and even more so for jazz, a style of music that often envelops you. Moser’s lyrics pull you out of that reverie, offering an opportunity to actively listen and learn.

“Obviously, a lot of those topics that I chose are from the viewpoint of a blind person who grew up in a very sighted society,” says Moser. “But still, even if you grew up around a lot of blind people, you’re still in this sighted society that’s built for sighted people. So every topic is related to that.”

“Even if you grew up around a lot of blind people, you’re still in this sighted society that’s built for sighted people.”

The title of the album is something Moser has felt for years. She created a podcast of the same name, in which she talks frankly about everything from how she does her makeup, to how she knows when she has her period, to how she keeps her place tidy.

“My dad and I, and my brothers and my mom, we were always talking about creating this movie called ‘Blind. So What?,’ about our family. [It would be] a documentary, because it’s kind of crazy: this Irish woman marrying this Austrian, and their children—two of them are blind. And they live in Ireland first and move to Austria, where we were always the crazy family in this super small village,” Moser recounts. “Then, when I started the podcast about blindness, obviously it’s about [being] blind, so what? I still live my life normally and can do everything. It was clear that the album would be named this as well.”

Ciara Moser's Gear

Moser’s parents started her on violin as a child, but she found her musical home when she picked up the bass.

Photo by Kaffee Siebenstern

Basses

- Fodera Emperor 6 Standard

- Fender American Elite Jazz Bass V

- Marco Marcustico

Amps

- Markbass Standard 104HR

- Markbass Traveler 121H

- Markbass Little Mark Tube 800

- Markbass Little Mark III

- Markbass Mini CMD 121P

Effects

- Zoom B6 Bass Multi-Effects Processor

- Boss DD-7 Digital Delay

- Boss AW-3 Dynamic Wah

- EHX Micro POG

- Dunlop DVP3 Volume (X)

Strings

- D’Addario NYXL32130s

Moser’s parents always instilled in her that she was just like everybody else, and her life would be no different than that of a sighted person.

“They felt music would be an important thing to help me build some skill sets as a blind child because it’s not only good for the ears, but also for motoric skills and for coordination, and for social interaction with other kids,” Moser says. “So I started learning violin when I was 2 and a half.” She played violin throughout her youth, even entering competitions, but it was with bass that Moser found a perfect fit. “For me,” she says, “the bass always had that role of being the glue.”

“They felt music would be an important thing to help me build some skill sets as a blind child.”

In her early teens, Moser played in a pop-rock band with her two brothers— her younger one is also blind—and two other friends. “It was called Blind Brats,” she laughs. Her first bass was a “super cheap” Ibanez, and an instructor would come to the family home to give her lessons.

Blind. So What?, which showcases Moser’s 6-string Fodera bass, was created as part of her master's of jazz performance program at the Berklee Global Jazz Institute.

Photo by Manuela Haeussler

In high school, she started to play in more bands, and after two years, she bought a Fender American Deluxe Jazz Bass. Around that time, her instructor suggested that she enroll at Borg Linz, a pop-music-focused high school in Linz, Austria, a half hour away from her house. Classes were divided into two bands and given recording projects, where students learned how to produce music and write songs.

“There, I started to play in my first professional funk band,” says Moser. “It was called Round Corner, and the guitarist got me in a fusion trio that he started with the same drummer of the band. That was the first time I started playing more complicated music—the music of Scott Henderson, Greg Howe, Guthrie Govan, those kinds of fusion guitar players. We also played some stuff from the band Lettuce. They were actually Berklee graduates, as well.

“If it’s really important, I normally ask somebody to tell me all the knobs on the amp. But, if we don’t have time, then I just have to work with my fingers and the bass.”

“And then I went to those yearly big-band workshops where you play in a big band and you also have instrumental lessons. And there, I started to play jazz, more straight-ahead.”

Moser then started going to college in Vienna, and a year later, decided she needed “at least a 5-string.” She drove all the way to Augsburg, Germany, to a shop called Station Music. “They had like 600 basses and I tried a lot of them,” she recalls. “There was this one Fodera bass that is now my bass. I really resonated with the sound and the feel of the instrument.

“It was the overall feel of the neck that I really loved—the wood of the neck makes a lot of difference. I feel like it even makes a slight difference in the sound, because I tried some of them with dark necks and with brighter necks. But, also, what I liked about that bass was the preamp, which is cool because later, at Berklee, I studied with Mike Pope, who designed that preamp with Fodera. It’s always been striking to me how in any rehearsal room I walk into, the preamp on the bass is so well-designed that I can put the EQ of the amp flat, then just work my way around it with the bass. That’s been something that’s been supporting me as a blind person because I can’t see all the knobs on the amp. If I have a gig, or if it’s really important, I normally ask somebody to tell me all the knobs on the amp. But, if we don’t have time, then I just have to work with my fingers and the bass.”

Moser says she has yet to do any in-depth modifications or have a luthier do a custom build, but she did add a “little secret.” “I have tape on the 7th fret and on the 12th fret on the back of the neck so I can jump to wherever I want, so I can have some anchor points on the bass,” she says, adding, “I’ve been so busy performing, and I’ve been so happy with what I’ve played right now that it’s been hard to convince myself to get a different product. But I’m open to trying new instruments and defining new pathways and sounds.”

Moser is involved with Austria’s blind community, and with her experience and successes, Moser wants to help guide young blind musicians.

Photo by Manuela Haeussler

Moser, who in October finished a master’s in instrumental and vocal pedagogy from the University of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna, just did a tour of Austria at eight venues and is in the process of booking festivals and shows for this year in Europe and the U.S. She also plans on releasing an additional EP that will feature a “Different Ability” suite, “because my journey has not ended regarding that.”

“It took me a while to understand that my disability is not a disability,” she says. “I always knew my disability is a characteristic, but I still put it down a lot. I should actually put it up and highlight it, but in a good way.”

“I always knew my disability is a characteristic, but I still put it down a lot. I should actually put it up and highlight it, but in a good way.”

Moser says sighted people should not feel uncomfortable about asking questions of blind people. At least, she doesn’t mind. “They say, ‘I’m so sorry to ask you, but are you blind from birth?’ And I’m like, ‘Why are you sorry to ask me that?’ It’s as if you ask me if I have brown hair or what my size is, you know what I mean? I don’t mind talking about that. It’s part of me and it’s always gonna be. I think for them, it’s just because they’re coming from their perspective and not from my perspective,” she reasons. “So, if they would be imagining themselves blind right now, they can’t because they don’t know how it works. It’s basically ignorance, and I’m used to it. I’m used to explaining that to people every day.”

Moser is an educator herself, who often works with young people and colleagues who are blind musicians. “In Austria, I’m very involved in a blind scene, and, also at Berklee, there are always between five and eight blind students,” she explains. “I would say I’m kind of like their consultor. They always ask me questions like, ‘How did you do this?’ and ‘How do you think this could be done?’ If I meet parents of a young blind child, it’s very important for me to have that role model position and to help, because I know it’s very challenging for parents of a blind child. But for the blind child, of course, it’s challenging as well. So I definitely want to take that role.”

YouTube It

Along with a killer ensemble featuring Nishant Shekar on vocals, Ciara Moser plays live in the studio in the music video for “I Trust,” and takes a dazzling, playful solo.

- How NOT to Play Bass like a Guitar Player Playing Bass ›

- Blending Bass With Acoustic Guitar ›

- DIY: How to Set Up a Bass Guitar ›

We’re giving away more gear! Enter Stompboxtober Day 24 for your chance to win today’s pedal from Maxon!

Maxon OD-9 Overdrive Pedal

The Maxon OD-9 Overdrive Effects Pedal may look like your old favorite but that's where the similarity ends. Improved circuitry with a new chip yields the ultra-smooth dynamic overdrive guitarists crave. Drive and Level controls tweak the intensity and volume while the Hi-Boost/Hi-Cut tone controls adjust brightness. Features true bypass switching, a die-cast zinc case, and 3-year warranty. From subtle cries to shattering screams, the Maxon OD-9 delivers a huge range of tones.

Features

Improved circuitry with a new chip yields ultra-smooth dynamic overdrive

Drive and Level controls tweak the intensity and volume

Hi Boost/Hi Cut tone controls adjust brightness

True bypass switching

Die-cast zinc case

AC/DC operation (order optional Maxon AC210N adapter)

Product Specs

Input: 1/4" mono jack

Output: 1/4" mono jack

Power: 9V DC, 6 mA, center pin minus (not included)

Dimensions: (WxDxH) 74 mm x 124 mm x 54 mm

Weight: 580g

Fender’s Greasebucket system is part of Cory Wong’s sonic strategy.

Here’s part two of our look under the hood of the funky rhythm guitar master’s signature 6-string.

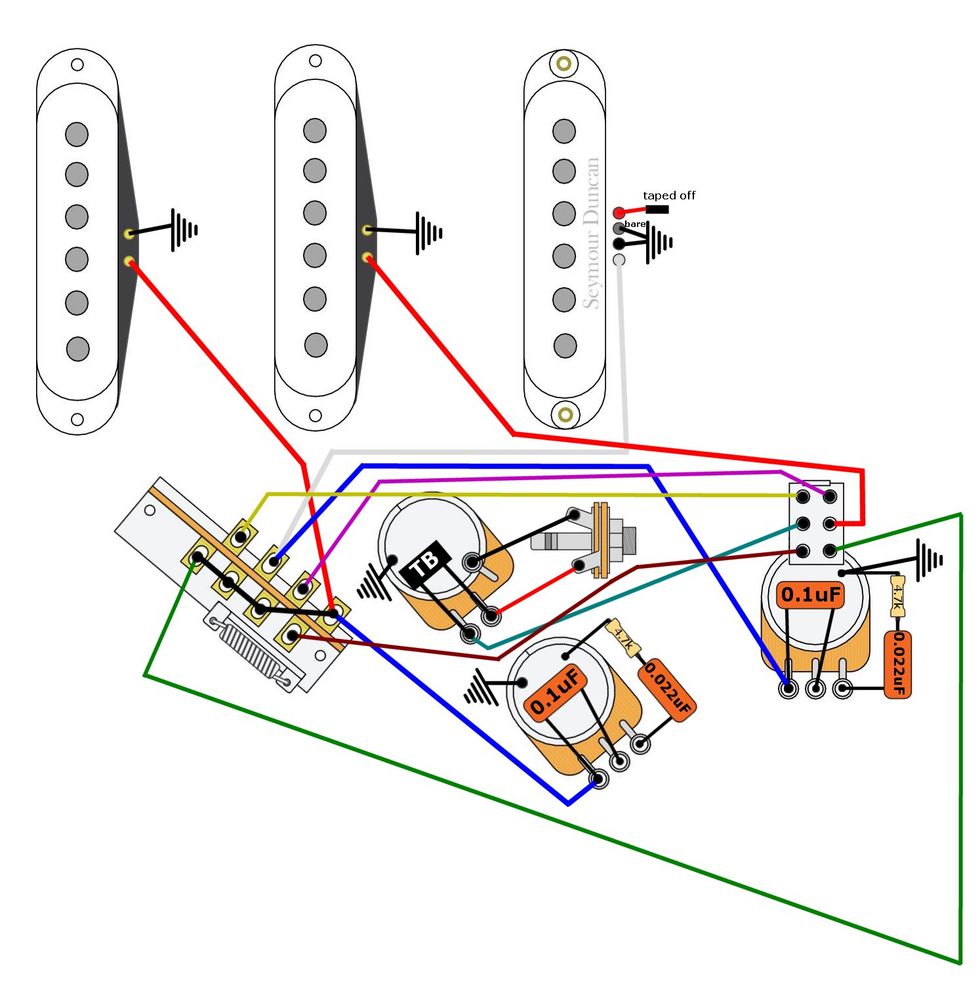

Hello and welcome back to Mod Garage. In this edition, we’re continuing our journey through the Fender Cory Wong Stratocaster wiring, bringing it all together.In the previous installment, the last feature on the funky 6-stringer’s signature axe that we discussed was the master volume pot and the corresponding treble-bleed circuit. Now, let’s continue with this guitar’s very special configuration of the tone pots.

Tone pot with Fender Greasebucket tone system:

This 250k tone pot is a standard CTS pot with a 90/10 audio taper found in all U.S.-built Fender guitars. The Cory Wong guitar uses the Fender Greasebucket system, which is added to the pot as a ready-to-solder PCB. The Greasebucket PCB is also available individually from Fender (part #7713546000), though you can use conventional electronic parts for this.

Fender introduced this feature in 2005 on some of the Highway One models and some assorted Custom Shop Strats. The Greasebucket name (which is a registered Fender trademark, by the way) is my favorite of Fender’s marketing names, but don’t let it fool you: Your tone will get cleaner with this modification, not greasy and dirty.

According to Fender, the Greasebucket tone circuit reduces high frequencies without adding bass as the tone knob is turned down. Don’t let that description confuse you. A standard Strat tone control does not add any bass frequencies! As you already know, with a passive system you can’t add anything that isn’t already there. You can reshape the tone by deemphasizing certain frequencies and making others more prominent. Removing highs makes lows more apparent and vice versa. In addition, the use of inductors (which is how a passive pickup behaves in a guitar circuit) and capacitors can create resonant peaks and valleys (band-passes and notches), further coloring the overall tone.

Cory Wong bringing the funk onstage.

This type of band-pass filter only allows certain frequencies to pass through, while others are blocked. The standard tone circuit in a Strat is called a variable low-pass filter (or a treble-cut filter), which only allows the low frequencies to pass through while the high frequencies get sent to ground via the tone cap.

The Greasebucket’s band-pass filter is a combination of a high-pass and a low-pass filter. This is supposed to cut high frequencies without “adding” bass, which has mostly to do with the resistor in series with the pot. That resistor means the control will never get to zero. You can get a similar effect by simply not turning the Strat’s standard tone control all the way down. (The additional cap on the wiper of the Greasebucket circuit complicates things a bit, though; together with the pickups it forms an RLC circuit, but I really don’t want to get into that here.)

The standard Fender Greasebucket tone system is used in the Cory Wong Strat, which includes a 0.1 μF cap and a 0.022 uF cap, along with a 4.7k-ohm resistor in series. These are the values used on the PCB, and without the PCB it looks like the illustration at the top of this column.

Push-push tone pot with preset overwriting function:

The lower tone pot assigned to the bridge pickup is a 250k audio push-push pot with a DPDT switch. The switch is used to engage a preset sound by overwriting the 5-way pickup-selector switch, no matter what switching position it is in. The preset functionality has a very long tradition in the house of Fender, dating back to the early ’50s, when Leo Fender designed a preset bass sound on position 3 (where the typical neck position is on a modern guitar) of the Broadcaster (and later the Telecaster) circuit. Wong loves the middle-and-neck-in-parallel pickup combination, so that’s the preset sound his push-push tone pot is wired for.

The neck pickup has a dedicated tone control while the middle pickup doesn’t, which is also another interesting feature. This means that when you hit the push-push switch, you will engage the neck and middle pickup together in parallel, no matter what you have dialed in on the 5-way switch. Hit the push-push switch again, and the 5-way switch is back to its normal functionality. Instead of a push-push pot, you can naturally use a push-pull pot or a DPDT toggle switch in combination with a normal 250k audio pot.

Here we go for the wiring. For a much clearer visualization, I used the international symbol for ground wherever possible instead of drawing another black wire, because we already have a ton of crossing wires in this drawing. I also simplified the treble-bleed circuit to keep things clearer; you’ll find the architecture of it with the correct values in the previous column.

Cory Wong Strat wiring

Courtesy of singlecoil.com

Wow, this really is a personalized signature guitar down to the bone, and Wong used his opportunity to create a unique instrument. Often, signature instruments deliver custom colors or very small aesthetic or functional details, so the Cory Wong Stratocaster really stands out.

That’s it! In our next column, we will continue our Stratocaster journey in the 70th year of this guitar by having a look at the famous Rory Gallagher Stratocaster, so stay tuned!

Until then ... keep on modding!

The Keeley ZOMA combines two of iconic amp effects—tremolo and reverb—into one pedal.

Key Features of the ZOMA

● Intuitive Control Layout: Three large knobs give you full control over Reverb Level, Tremolo Rate,and Depth

● Easy Access to Alternate Controls: Adjust Reverb Decay, Reverb Tone, and Tremolo Volume withsimple alt-controls.

● Instant Effect Order Switching: Customize your signal path. Position tremolos after reverb for avintage, black-panel tone or place harmonic tremolo before reverb for a dirty, swampy sound.

● True Bypass or Buffered Trails: Choose the setting that best suits your rig.

Three Reverb and Tremolo Modes:

● SS – Spring Reverb & Sine Tremolo: Classic spring reverb paired with a sine wave tremolo for that timelessblack-panel amp tone.

● PH – Plate Reverb & Harmonic Tremolo: Smooth, bright plate reverb combined with swampy harmonictremolo.

● PV – Plate Reverb & Pitch Vibrato: Achieve a vocal-like vibrato with ethereal plate reverb.

Reverb: Sounds & Controls

● Spring Reverb: Authentic tube amp spring reverb that captures every detail of vintage sound.

● Plate Reverb: Bright and smooth, recreating the lush tones of vibrating metal plates.

● Reverb Decay: Adjust the decay time using the REVERB/ALT SWITCH while turning the Level knob.

● Reverb Tone: Modify the tone of your reverb using the REVERB/ALT SWITCH while turning the Rate knob.

Tremolo: Sounds & Controls

● Sine Wave/Volume Tremolo: Adjusts the volume of the signal up and down with smooth sine wavemodulation.

● Harmonic Tremolo: Replicates classic tube-amp harmonic tremolo, creating a phaser-like effect withphase-split filtering.

● Pitch Vibrato: Delivers pitch bending effects that let you control how far and how fast notes shift.

● Alt-Control Tremolo Boost Volume: Adjust the boost volume by holding the REVERB/ALT footswitch whileturning the Depth knob.

The ZOMA is built with artfully designed circuitry and housed in a proprietary angled aluminum enclosure, ensuring both simplicity and durability. Like all Keeley pedals, it’s proudly designed and manufactured in the USA.

ZOMA Stereo Reverb and Tremolo

The first sound effects built into amplifiers were tremolo and reverb. Keeley’s legendary reverbs are paired with their sultry, vocal-like tremolos to give you an unreal sonic experience.

Your 100 Guitarists hosts are too young to have experienced SRV live. We’ve spent decades with the records, live bootlegs, and videos, but we’ll never know quite how it felt to be in the room with SRV’s guitar sound.

Stevie Ray Vaughan was a force of nature. With his “Number One” Strat, he drove a veritable trove of amps—including vintage Fenders, a rotating Vibratone cab, and a Dumble—to create one of the most compelling tones of all, capable of buttery warmth, percussive pick articulation, and cathartic, screaming excess. As he drew upon an endless well of deeply informed blues guitar vocabulary, his creativity on the instrument seemingly knew no bounds.

Your 100 Guitarists hosts are too young to have experienced SRV live. We’ve spent decades with the records, live bootlegs, and videos, but we’ll never know quite how it felt to be in the room with SRV’s guitar sound. So, we’d like to spend some time imagining: How did it feel when it hit you? How did he command his band, Double Trouble? The audience?

SRV was mythical. His heavy-gauge strings tore up his fingers and made a generation of blues guitarists work a lot harder. And his wall of amps seems finely curated to push as much air in all directions as possible. How far did he take it? Was he fine-tuning his amps to extreme degrees? Or could he get his sound out of anything he plugged into?