|

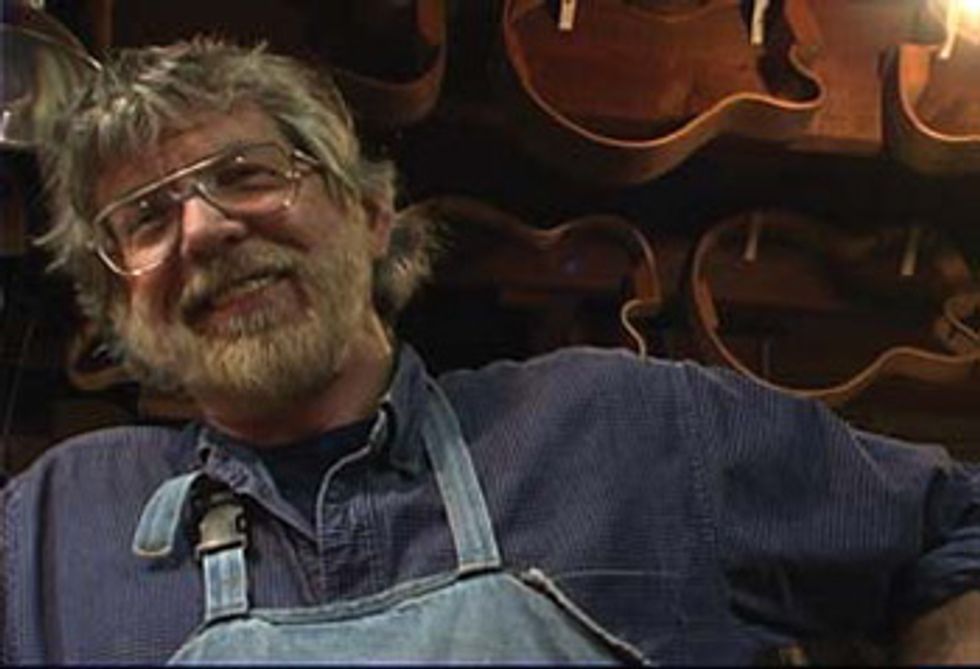

Between 1972 and 2010, Ribbecke has covered a lot of ground in the guitar world. Starting with solidbodies—“because they’re easy”—he was quickly enamored with the way steel-string tops vibrate. “I became fascinated with what I started to call the ‘z axis.’ When you look at the way the top behaves on a guitar as an energy machine, we generally look at whether it’s flat or arched—but almost nobody screws around with that axis, the actual carving or shape of it. I became uniquely aware, because I’ve always been fascinated with physics, that the top of the guitar is really a radiator, and the soundhole is really a port for bass. The guitar is really a speaker enclosure.”

Though this discovery affected all of Ribbecke’s subsequent designs, including the thinline and flattop models he still offers, it was especially instrumental in Ribbecke’s famed Halfling model. For archtop aficionados, it’s no stretch of the imagination to say that the Halfling represents a revolution in archtop technology—the culmination of 30 years of experience, research, observation, and a profound desire to contribute something truly meaningful to the development of the instrument. “I looked around and saw a lot of incredible steel-strings that were mostly reduxes of Martins and Gibsons,” Ribbecke recalls. “But when I started playing the archtop, it became clear to me that the instrument was really undeveloped, really in its infancy. Archtops started with Lloyd Loar, and they’re less than 100 years old as a real design. I felt that there was room to innovate in that area, and I became incredibly fascinated with the structural challenge of building an archtop guitar.”

The “Grandfatherly” Artist in the Family

|

It never occurred to Ribbecke to not build guitars once he’d made up his mind to do it. “My father infused me with this ability to make things,” he says. “If I thought I could do it, I could just do it. I didn’t think there was any reason that you couldn’t make something if you just saw it. That’s what he gave me by way of encouragement—I saw him doing it. My brother was an MIT engineer and my father was a chemist, so I’m sort of ‘the artist,’ but I still have all of that scientific imperative. I grew up with it.”

But very few guitar-building resources were available when Ribbecke got started. “In those days, there was an Arthur Overholtzer book [Classic Guitar Making], which was as ponderous as Arthur was himself. There was a David Russell Young book [The Steel String Guitar: Construction & Repair] about steel-string guitars, and the [Hideo] Kamamoto book, which was called Complete Guitar Repair. I spent six months in the library, and there was no one to study with around me. There was literally nobody doing this that I could find.”

Even so, commissions started coming in from the repair shop he opened on San Francisco’s Guerrero Street. “I would lure customers in, refret their guitars, repair them,” he reminisces. “And I began to sell instruments most handily that way, because I had a little storefront window I could put a little solidbody guitar in, and one thing led to the next. By about the second year of making, I became fascinated with the science of acoustics.”

The first innovation Ribbecke made waves with was the Sound Bubble steel-string. In fact, he says that’s what led to “the whole Halfling thing.” Sound Bubbles looked like conventional steel-strings with a little bubble carved in the bass side of the soundboard. They had a natural flanged sound, but didn’t have the huge bass response that Ribbecke and his partner at the time, Charles Kelly, were hoping for. “I still didn’t know what the hell I was doing at that age,” he says with a laugh, “but I built a lot of those guitars—they still come back to me. There are collectors of those instruments, and they have a unique and beautiful sound, but I never felt that was an idea that I truly realized.”

Conceptualizing a Texturizing Machine

|

Launching into what he calls his “California touchy-feely thing” (his shops are located in Healdsburg, California), Ribbecke begins to explain a bit of his thought process. “My whole acoustic paradigm is that guitars are energy machines. They convert energy from one form to another, but they’re not very efficient. When you hear a couple of piano strings vibrating against each other, they’re tuned to the same pitch, and you hear the texture that resolves because they are not able to stay perfectly in pitch with each other. You hear this beating that goes on, and we hear this as texture. I became aware that the shape of a guitar top creates an acoustic texture, and I understood very clearly that there was some real-time parameter about this. But I didn’t know how to deal with this concept that a carved-up part of a soundboard that is much more arched and much more stiff will actually excite air at a much higher frequency and much faster than something that’s flatter and more bass compliant, like a steel-string guitar.”

Ribbecke’s dissatisfaction with archtop guitars had to do with one of the things that makes them do what they were designed to do, which is cancel bass to create separation of course—the ability to hear complex close tones. “Like a minor 9,” says Ribbecke. “You can hear it in an archtop guitar because the top is not moving in the 1 kHz range—it’s much more articulate. It’s much easier to hear complex clusters of notes and chords. So you can play great jazz chords with very close harmonic tones. You can still hear each and every note in the chord. Archtops have great separation of course, but are nasal in their bass response because they’re carved up. Bass has a tendency to shake things in the 1 or 2 kHz range, which is where most of our information is.”

The steel-string guitar, he continues, “is very loud and very beautiful, but very hard to differentiate when someone is strumming, because the top is so much freer to move. It’s such a more expansive and dynamic distance that it can move. So it sort of overwhelms itself with information in the 1 to 2 kHz range, and it becomes very hard to differentiate every note in a chord.”

The Halfling Under a Microscope

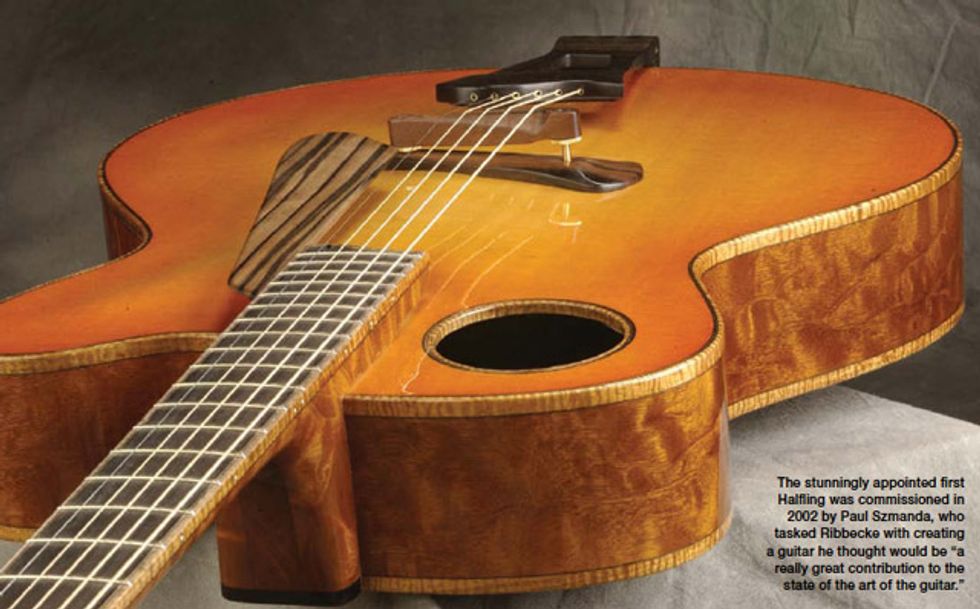

Ribbecke’s Halfling is a beautiful hybrid with a flat top on the bass side, an archtop on the treble side, and an X-brace structure. Ribbecke explains that it’s as if “you took a Martin and sawed it in half, and glued the bass half to an archtop that’s similarly bisected. You’d have the treble side of the archtop and the bass side of the steel-string guitar.” The net result on the Halfling is that the bass side of the soundboard is more compliant and rich—able to reproduce the big bass and deeper, throatier sound—but the carved treble side allows the instrument to have a great separation of course and behave like an archtop.

“So the Halflings are really archtop guitars with an enhanced and developed mid and bass range—without phase cancellation.” Ribbecke reasoned that very few things in nature are truly symmetrical and began with the idea that “symmetry was the hobgoblin, the opium for the acoustic mind. But it really isn’t, both in nature and in the way our ears hear. It takes a lot more energy to make a bass note audible than it does a treble note, and if you look at the curve of human hearing, it’s also like that.”

Another asymmetrical appointment on the Halfling is its bass-side, upper-bout soundhole, which allows that side to be thinned more without weakening it by punching a hole in the middle. “It’s a nice aesthetic design,” Ribbecke continues, “and I’m not the first guy to think of it. I studied with Richard Snyder, who was phenomenal and had his on the other side of the soundboard, but I’ve stolen those ideas from everybody who came before me. The concept of the Halfling as a whole, as a piece of art, is to free the bass side of the soundboard to be more compliant and still have a instrument that’s truly an archtop in structure and design.”

The first Halfling was commissioned by Paul Szmanda, a player and collector of some extraordinary guitars. “Paul called me one day and he said, ‘What would you do if I gave you a chance to just build something that you think is going to be historically significant? No fetters on this commission. Make something you think will be a really great contribution to the state of the art of the guitar.’ That must have been 2002. That’s the one you’ll see all over the place, with the quilted mahogany. It’s on my website. It’s a pretty amazing instrument, visually. I’d been waiting for probably 15 years for somebody to say, ‘Can you make a modern embodiment of the Sound Bubble concept that now works because you know a lot more about what you’re doing than you did when you were an idiot 22-year-old?’”

But the Halfling is more than an archtop jazz guitar—it’s an instrument that can keep up with players who play steel-string one minute, then archtop, then electric guitar. “The modern guitar players we have today, these guys have studied. There’s so much information available on the ’net. We have a new breed of guitar player who plays standards, plays steel-string guitar, plays all these different literatures. The quality of the average guitar player is through the roof right now, compared to what it was 30 years ago. I don’t think this Halfling thing would have worked out were it 15 years ago, but now I think there’s a market for an instrument that will allow somebody to do cross-literatures.”

The Halfling Bass is another of Ribbecke’s innovations, and it was undertaken in collaboration with bassist Bobby Vega. “He speaks in a language that’s not like what we speak,” says Ribbecke with a touch of awe. “He talks about notes coming from here and here, and he points to different places. I couldn’t make him just another big bass that was supposed to be a guitar, so he waited seven years for this thing while I tried to figure out what to do to make this really special for him. Bobby and I worked very closely. He’s got an incredible bass—it’s archival—and we took the same dimensions on the Halfling bass, and we moved the tailpiece all over the place. I’ve never known anybody who can hear like him. I think I can hear pretty well, but he hears things I can’t even begin to hear. So we worked very closely on this bass until, as he would say, it ‘fired right’—until it had this dimension.”

When Lofty Goals Converge

The partnerships that developed between Ribbecke, Szmanda, and Vega, along with CFO Len Wood, became the energy behind the Ribbecke Guitar Corporation (RGC). “Because of luck of the draw—where the economy was when these instruments appeared on the scene—we were fortunate enough to have people step forward and invest and help me make these things. We obtained a patent on it, we had a group of investors step forward and opened a corporation—kind of a nutty, alternative corporation— to build the Halflings. We’ve built and sold close to a million dollars worth of Halflings in the last six years. I wanted to rebrand myself at about a third of the price, wrap in some technology, really offer something different, and build them in America. We made a very conscious decision not to take this offshore, because I felt that the technology could be screwed up very quickly and easily. So we slog along here making them in America.”

Taking a “guerilla” approach, RGC decided the best strategy would be to run the business as lean as possible instead of taking on millions of dollars in debt. “We took angelic investors who really believed in the product and started the company with a little less than $600,000 and ran it on a shoestring with an unbelievable crew of people who were all hand-selected—all of whom are really special. I think that’s why we’re still here today, because we chose the guerilla method to build this company. If we had taken venture capital, or if we had taken money from anyplace else, I think we would be out of business now.” Ribbecke’s private workshop is located three miles from the RGC workshop, but he currently spends 80 to 85 percent of his time building Halflings.

RGC’s other mission was completely accidental. It was poles apart from Ribbecke’s goal of changing the archtop world, but it was perhaps far more important. Several years ago, a friend asked if she could bring her son out to the shop to do some sweeping up or other work for Ribbecke—he was setting fires and getting into trouble and she needed to do something. Ribbecke politely declined, but she showed up anyway, and he took the youngster on. “He was particularly troubled. He had been a young white supremacist—I went to his MySpace page and it was all in German! I used to call him Himmler [after Heinrich Himmler, Adolf Hitler’s infamous SS officer during World War II]. But he seemed to think what I did was cool. It wasn’t long before his life had changed and his MySpace page was in English and he had gay friends and black friends—because people would just call him out on his behavior in my shop. After a while the school started calling me, saying, ‘Well, we’ve got this other kid . . . .’ That’s kind of how that whole thing started.”

Some documentary filmmakers approached Ribbecke about doing a film about his life and the two businesses he ran side by side. When they observed the people in the shop and how Ribbecke interacted with them, they immediately began talking about a reality TV series, which was to be called Ribbecke’s Guitar Planet. The trailer opens with Ribbecke saying that he is trying to pass on his knowledge before “they burn the place down.” He’s being tongue-incheek, of course. But, all kidding aside, he’s very proud of this “family” that surrounds his instruments. “If nothing else comes out of this, the fact that we’ve had this experience, and these kids have had this chance to grow and be who they are—they would have done this with or without us, maybe—but I was privileged to be with them when this all happened. It’s just been phenomenal.

|

Ribbecke’s Guitar Planet was purchased by the producers of Extreme Home Makeover, but is currently simmering on a back burner. Ribbecke believes the current economy is such that it probably won’t air, but you can still view the trailer online. Go to guitarplanet.org and click on the “Promo Clip” link at the bottom of the page.

The Final 25

Ribbecke recently made an announcement on his website that he was accepting the last 25 orders for his private workshop. “There’s a four- to five-year wait for a guitar from my private shop. I’m 58 years old and I’ve been doing this 15 hours a day my whole life. I don’t know how to live in a moderate way, so this is what I’ve done. The Final 25 guitars are guitars that nobody else touches but me. My helpers don’t work on them—they’re my final work. And each one of them I want to be extraordinary. It’s not about decorative work as much as it’s about art and design. I don’t want to do tons of inlay. I’ll be working with shapes and sonic development. I’ve got some instruments that I don’t even want to talk about yet, because they’re new developments. I just figured out a new way to buffer the rim of a soundboard, which I think will be very microphonic. I think it will create a whole new type of instrument. But each of those final 25 orders will be the best that I can do—museum-quality pieces that I’ve built with materials I’ve been stashing for 38 years. The best material that I have. The most focus from me. The highest way that I can realize whatever their dream is.”

Which brings us back to dreams and the stuff they’re made of. Like Honduran mahogany, German spruce, and the pure mojo of people who are in it because they truly love it. Ribbecke’s father taught him the true meaning of the Latin word amateur many years ago. “He used to say, ‘Thirty years from now, I hope you can tell me you still love these guitars,’ and that’s a lesson I’ve never forgotten. Every day I think about that, and even when I hate doing what I’m doing I find a way to love it because that’s what’s essential to keep it going.”