There are superstars of country and rock, chart-toppers, and guitar heroes. Then there’s Keith Urban. His two dozen No. 1 singles and boatloads of awards may not eclipse George Strait or Garth Brooks, but he’s steadily transcending the notion of what it means to be a country star.

He’s in the Songwriters Hall of Fame. He’s won 13 Country Music Association Awards, nine CMT video awards, eight ARIA (Australian Recording Industry Association) Awards, four American Music Awards, and racked up BMI Country Awards for 25 different singles.

He’s been a judge on American Idol and The Voice. In conjunction with Yamaha, he has his own brand of affordably priced Urban guitars and amps, and he has posted beginner guitar lessons on YouTube. His 2014 Academy of Country Music Award-winning video for “Highways Don’t Care” featured Tim McGraw and Keith’s former opening act, Taylor Swift. Add his marriage to fellow Aussie, the actress Nicole Kidman, and he’s seen enough red carpet to cover a football field.

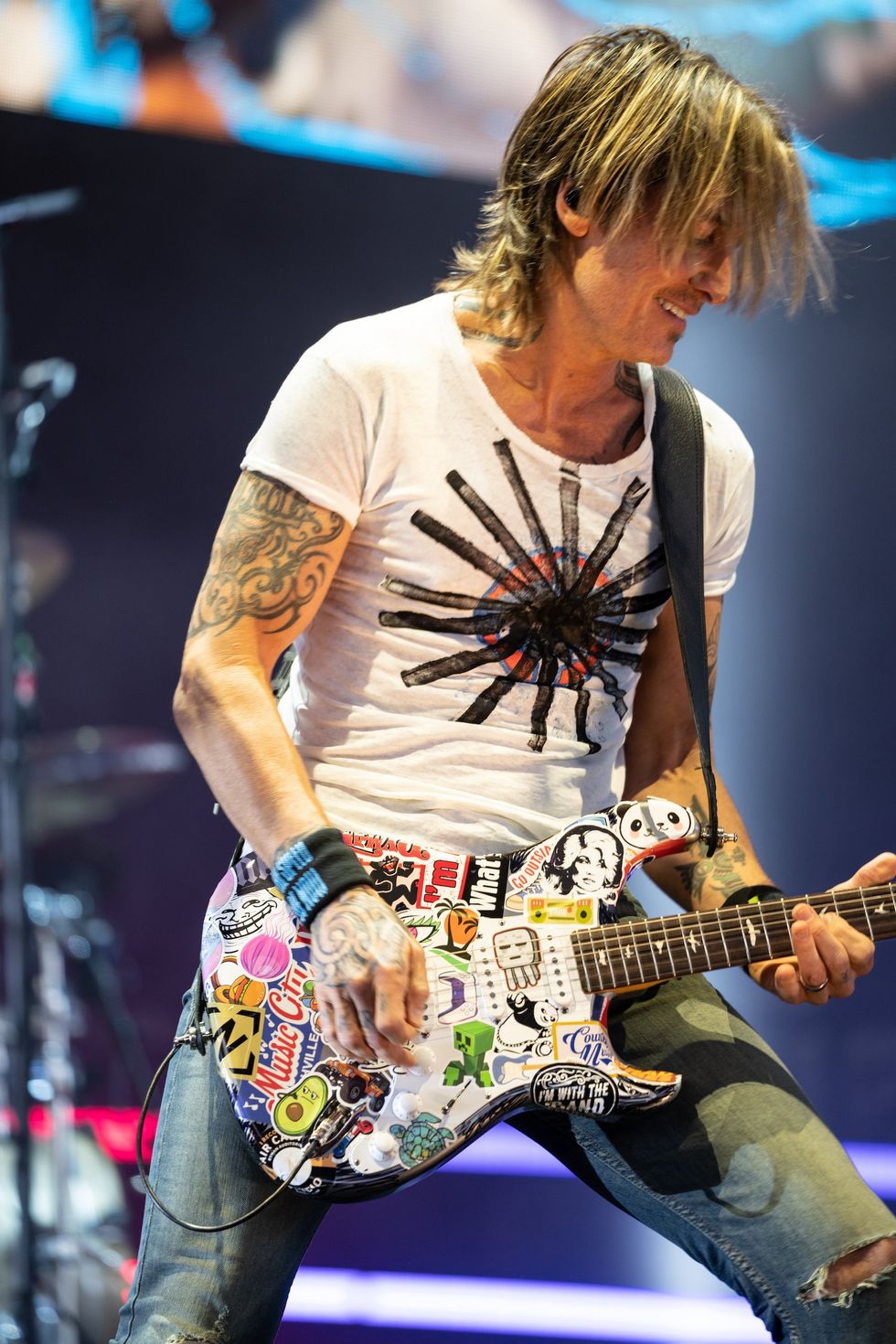

Significantly, his four Grammys were all for Country Male Vocal Performance. A constant refrain among newcomers is, “and he’s a really good guitar player,” as if by surprise or an afterthought. Especially onstage, his chops are in full force. There are country elements, to be sure, but rock, blues, and pop influences like Mark Knopfler are front and center.

Unafraid to push the envelope, 2020’s The Speed of Now Part 1 mixed drum machines, processed vocals, and a duet with Pink with his “ganjo”—an instrument constructed of a 6-string guitar neck on a banjo body—and even a didgeridoo. It, too, shot to No. 1 on the Billboard Country chart and climbed to No. 7 on the pop chart.

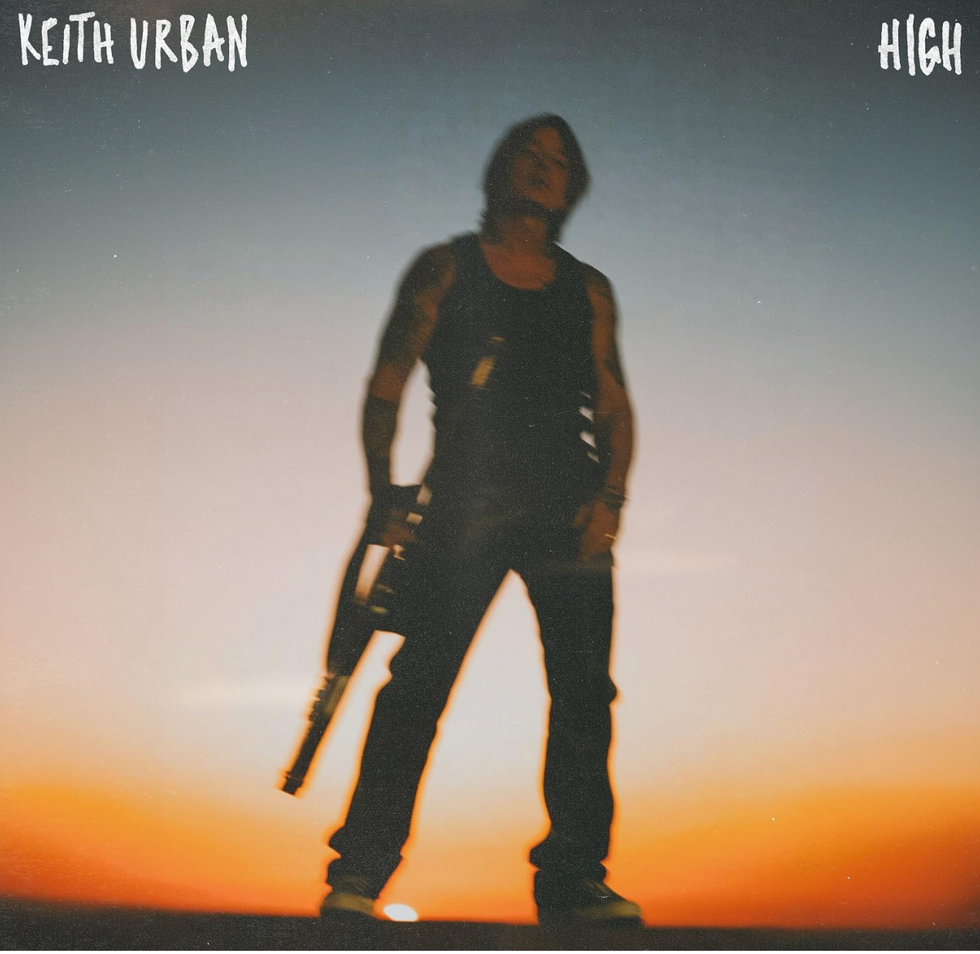

His new release, High, is more down-to-earth, but is not without a few wrinkles. He employs an EBow on “Messed Up As Me” and, on “Wildfire,” makes use of a sequencer reminiscent of ZZ Top’s “Legs.” Background vocals in “Straight Lines” imitate a horn section, and this time out he duets on “Go Home W U” with rising country star Lainey Wilson. The video for “Heart Like a Hometown” is full of home movies and family photos of a young Urban dwarfed by even a 3/4-size Suzuki nylon-string.

Born Keith Urbahn (his surname’s original spelling) in New Zealand, his family moved to Queensland, Australia, when he was 2. He took up guitar at 6, two years after receiving his beloved ukulele. He released his self-titled debut album in 1991 for the Australian-only market, and moved to Nashville two years later. It wasn’t until ’97 that he put out a group effort, fronting the Ranch, and another self-titled album marked his American debut as a leader, in ’99. It eventually went platinum—a pattern that’s become almost routine.

The 57-year-old’s celebrity and wealth were hard-earned and certainly a far cry from his humble beginnings. “Australia is a very working-class country, certainly when I was growing up, and I definitely come from working-class parents,” he details. “My dad loved all the American country artists, like Johnny Cash, Haggard, Waylon. He didn’t play professionally, but before he got married he played drums in a band, and my grandfather and uncles all played instruments.

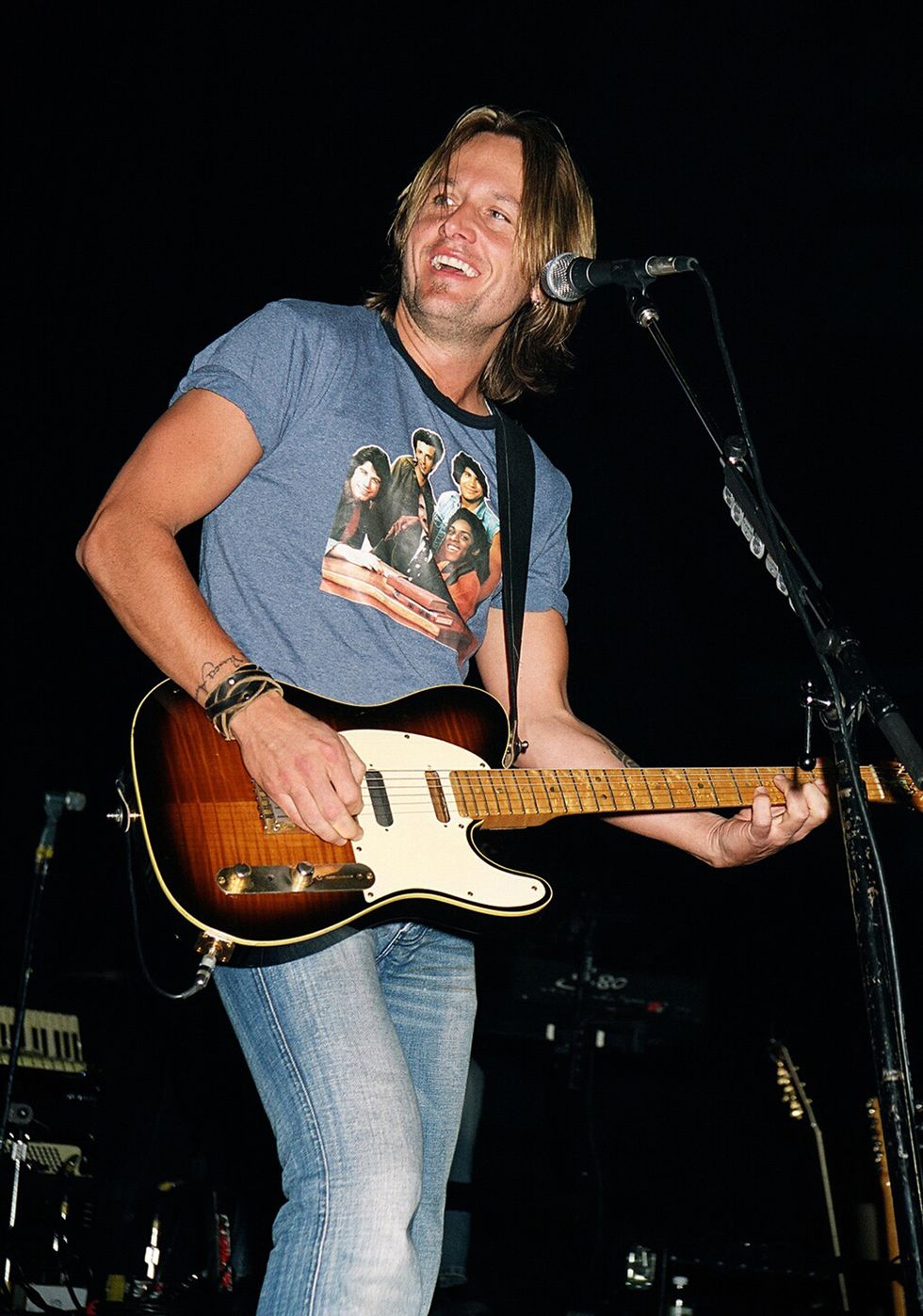

One of Urban’s biggest influences as a young guitar player was Mark Knopfler, but he was also mesmerized by lesser-known session musicians such as Albert Lee, Ian Bairnson, Reggie Young, and Ray Flacke. Here, he’s playing a 1950 Broadcaster once owned by Waylon Jennings that was a gift from Nicole Kidman, his wife.

“For me, it was a mix of that and Top 40 radio, which at the time was much more diverse than it is now. You would just hear way more genres, and Australia itself had its own, what they call Aussie pub rock—very blue-collar, hard-driving music for the testosterone-fueled teenager. Grimy, sweaty, kind of raw themes.”

A memorable event happened when he was 7. “My dad got tickets for the whole family to see Johnny Cash. He even bought us little Western shirts and bolo ties. It was amazing.”

But the ukulele he was gifted a few years earlier, at the age of 4, became a constant companion. “I think to some degree it was my version of the stuffed animal, something that was mine, and I felt safe with it. My dad said I would strum it in time to all the songs on the radio, and he told my mom, ‘He’s got rhythm. I wonder what a good age is for him to learn chords.’ My mom and dad ran a little corner store, and a lady named Sue McCarthy asked if she could put an ad in the window offering guitar lessons. They said, ‘If you teach our kid for free, we’ll put your ad in the window.’”

Yet, guitar didn’t come without problems. “With the guitar, my fingers hurt like hell,” he laughs, “and I started conveniently leaving the house whenever the guitar teacher would show up. Typical kid. I don’t wanna learn, I just wanna be able to do it. It didn’t feel like any fun. My dad called me in and went, ‘What the hell? The teacher comes here for lessons. What’s the problem?’ I said I didn’t want to do it anymore. He just said, ‘Okay, then don’t do it.’ Kind of reverse psychology, right? So I just stayed with it and persevered. Once I learned a few chords, it was the same feeling when any of us learn how to be moving on a bike with two wheels and nobody holding us up. That’s what those first chords felt like in my hands.”

Keith Urban's Gear

Urban has 13 Country Music Association Awards, nine CMT video awards, eight ARIA Awards, and four Grammys to his name—the last of which are all for Best Country Male Vocal Performance.

Guitars

For touring:

- Maton Diesel Special

- Maton EBG808TE Tommy Emmanuel Signature

- 1957 Gibson Les Paul Junior, TV yellow

- 1959 Gibson ES-345 (with Varitone turned into a master volume)

- Fender 40th Anniversary Tele, “Clarence”

- Two first-generation Fender Eric Clapton Stratocasters (One is black with DiMarzio Area ’67 pickups, standard tuning. The other is pewter gray, loaded with Fralin “real ’54” pickups, tuned down a half-step.)

- John Bolin Telecaster (has a Babicz bridge with a single humbucker and a single volume control. Standard tuning.)

- PRS Paul’s Guitar (with two of their narrowfield humbuckers. Standard tuning.)

- Yamaha Keith Urban Acoustic Guitar (with EMG ACS soundhole pickups)

- Deering “ganjo”

Amps

- Mid-’60s black-panel Fender Showman (modified by Chris Miller, with oversized transformers to power 6550 tubes; 130 watts)

- 100-watt Dumble Overdrive Special (built with reverb included)

- Two Pacific Woodworks 1x12 ported cabinets (Both are loaded with EV BlackLabel Zakk Wylde signature speakers and can handle 300 watts each.)

Effects

- Two Boss SD-1W Waza Craft Super Overdrives with different settings

- Mr. Black SuperMoon Chrome

- FXengineering RAF Mirage Compressor

- Ibanez TS9 with Tamura Mod

- Boss BD-2 Blues Driver

- J. Rockett Audio .45 Caliber Overdrive

- Pro Co RAT 2

- Radial Engineering JX44 (for guitar distribution)

- Fractal Audio Axe-Fx XL+ (for acoustic guitars)

- Two Fractal Audio Axe-Fx III (one for electric guitar, one for bass)

- Bricasti Design Model 7 Stereo Reverb Processor

- RJM Effect Gizmo (for pedal loops)

(Note: All delays, reverb, chorus, etc. is done post amp. The signal is captured with microphones first then processed by Axe-Fx and other gear.)

- Shure Axient Digital Wireless Microphone System

Strings & Picks

- D’Addario NYXL (.011–.049; electric)

- D’Addario EJ16 (.012–.053; acoustics)

- D’Addario EJ16, for ganjo (.012–.053; much thicker than a typical banjo strings)

- D’Addario 1.0 mm signature picks

He vividly remembers the first song he was able to play after “corny songs like ‘Mama’s little baby loves shortnin’ bread.’” He recalls, “There was a song I loved by the Stylistics, ‘You Make Me Feel Brand New.’ My guitar teacher brought in the sheet music, so not only did I have the words, but above them were the chords. I strummed the first chord, and went, [sings E to Am] ‘My love,’ and then minor, ‘I'll never find the words, my,’ back to the original chord, ‘love.’ Even now, I get covered in chills thinking what it felt like to sing and put that chord sequence together.”

After the nylon-string Suzuki, he got his first electric at 9. “It was an Ibanez copy of a Telecaster Custom—the classic dark walnut with the mother-of-pearl pickguard. My first Fender was a Stratocaster. I wanted one so badly. I’d just discovered Mark Knopfler, and I only wanted a red Strat, because that’s what Knopfler had. And he had a red Strat because of Hank Marvin. All roads lead to Hank!”

He clarifies, “Remember a short-lived run of guitar that Fender did around 1980–’81, simply called ‘the Strat’? I got talked into buying one of those, and the thing weighed a ton. Ridiculously heavy. But I was just smitten when it arrived. ‘Sultans of Swing’ was the first thing I played on it. ‘Oh my god! I sound a bit like Mark.’”

“Messed Up As Me” has some licks reminiscent of Knopfler. “I think he influenced a huge amount of my fingerpicking and melodic choices. I devoured those records more than any other guitar player. ‘Tunnel of Love,’ ‘Love over Gold,’ ‘Telegraph Road,’ the first Dire Straits album, and Communiqué. I was spellbound by Mark’s touch, tone, and melodic choice every time.”

Other influences are more obscure. “There were lots of session guitar players whose solos I was loving, but had no clue who they were,” he explains. “A good example was Ian Bairnson in the Scottish band Pilot and the Alan Parsons Project. It was only in the last handful of years that I stumbled upon him and did a deep dive, and realized he played the solo on ‘Wuthering Heights’ by Kate Bush, ‘Eye in the Sky’ by Alan Parsons, ‘It’s Magic’ and ‘January’ by Pilot—all these songs that spoke to me growing up. I also feel like a lot of local-band guitar players are inspirations—they certainly were to me. They didn’t have a name, the band wasn’t famous, but when you’re 12 or 13, watching Barry Clough and guys in cover bands, it’s, ‘Man, I wish I could play like that.’”

On High, Urban keeps things song-oriented, playing short and economical solos.

In terms of country guitarists, he nods, “Again, a lot of session players whose names I didn’t know, like Reggie Young. The first names I think would be Albert Lee and Ray Flacke, whose chicken pickin’ stuff on the Ricky Skaggs records became a big influence. ‘How is he doing that?’”

Flacke played a role in a humorous juxtaposition. “I camped out to see Iron Maiden,” Urban recounts. “They’d just put out Number of the Beast, and I was a big fan. I was 15, so my hormones were raging. I’d been playing country since I was 6, 7, 8 years old. But this new heavy metal thing is totally speaking to me. So I joined a heavy metal band called Fractured Mirror, just as their guitar player. At the same time, I also discovered Ricky Skaggs and Highways and Heartaches. What is this chicken pickin’ thing? One night I was in the metal band, doing a Judas Priest song or Saxon. They threw me a solo, and through my red Strat, plugged into a Marshall stack that belonged to the lead singer, I shredded this high-distortion, chicken pickin’ solo. The lead singer looked at me like, ‘What the fuck are you doing?’ I got fired from the band.”

Although at 15 he “floated around different kinds of music and bands,” when he was 21 he saw John Mellencamp. “He’d just put out Lonesome Jubilee. I’d been in bands covering ‘Hurts So Good,' ‘Jack & Diane,’ and all the early shit. This record had fiddle and mandolin and acoustic guitars, wall of electrics, drums—the most amazing fusion of things. I saw that concert, and this epiphany happened so profoundly. I looked at the stage and thought, ‘Whoa! I get it. You take all your influences and make your own thing. That’s what John did. I’m not gonna think about genre; I’m gonna take all the things I love and find my way.’

“Of course, getting to Nashville with that recipe wasn’t going to fly in 1993,” he laughs. “Took me another seven-plus years to really start getting some traction in that town.”

Urban’s main amp today is a Dumble Overdrive Reverb, which used to belong to John Mayer. He also owns a bass amp that Alexander Dumble built for himself.

Photo by Jim Summaria

When it comes to “crossover” in country music, one thinks of Glen Campbell, Kenny Rogers, Garth Brooks, and Dolly Parton’s more commercial singles like “Two Doors Down.” Regarding the often polarizing subject and, indeed, what constitutes country music, it’s obvious that Urban has thought a lot—and probably been asked a lot—about the syndrome. The Speed of Now Part 1 blurs so many lines, it makes Shania Twain sound like Mother Maybelle Carter. Well, almost.

“I can’t speak for any other artists, but to me, it’s always organic,” he begins. “Anybody that’s ever seen me play live would notice that I cover a huge stylistic field of music, incorporating my influences, from country, Top 40, rock, pop, soft rock, bluegrass, real country. That’s how you get songs like ‘Kiss a Girl’—maybe more ’70s influence than anything else.”

“I think [Mark Knopfler] influenced a huge amount of my fingerpicking and melodic choices. I devoured those records more than any other guitar player.”

Citing ’50s producers Chet Atkins and Owen Bradley, who moved the genre from hillbilly to the more sophisticated countrypolitan, Keith argues, “In the history of country music, this is exactly the same as it has always been. Patsy Cline doing ‘Walking After Midnight’ or ‘Crazy’; it ain’t Bob Wills. It ain’t Hank Williams. It’s a new sound, drawing on pop elements. That’s the 1950s, and it has never changed. I’ve always seen country like a lung, that expands outwards because it embraces new sounds, new artists, new fusions, to find a bigger audience. Then it feels, ‘We’ve lost our way. Holy crap, I don’t even know who we are,’ and it shrinks back down again. Because a purist in the traditional sense comes along, whether it be Ricky Skaggs or Randy Travis. The only thing that I think has changed is there’s portals now for everything, which didn’t used to exist. There isn’t one central control area that would yell at everybody, ‘You’ve got to bring it back to the center.’ I don’t know that we have that center anymore.”

Stating his position regarding the current crop of talent, he reflects, “To someone who says, ‘That’s not country music,’ I always go, “‘It’s not your country music; it’s somebody else’s country music.’ I don’t believe anybody has a right to say something’s not anything. It’s been amazing watching this generation actually say, ‘Can we get back to a bit of purity? Can we get real guitars and real storytelling?’ So you’ve seen the explosion of Zach Bryan and Tyler Childers who are way purer than the previous generation of country music.”

Seen performing here in 2003, Urban is celebrated mostly for his songwriting, but is also an excellent guitarist.

Photo by Steve Trager/Frank White Photo Agency

As for the actual recording process, he notes, “This always shocks people, but ‘Chattahoochee’ by Alan Jackson is all drum machine. I write songs on acoustic guitar and drum machine, or drum machine and banjo. Of course, you go into the studio and replace that with a drummer. But my very first official single, in 1999, was ‘It’s a Love Thing,’ and it literally opens with a drum loop and an acoustic guitar riff. Then the drummer comes in. But the loop never goes away, and you hear it crystal clear. I haven’t changed much about that approach.”

On the road, Urban utilizes different electrics “almost always because of different pickups—single-coil, humbucker, P-90. And then one that’s tuned down a half-step for a few songs in half-keys. Tele, Strat, Les Paul, a couple of others for color. I’ve got a John Bolin guitar that I love—the feel of it. It’s a Tele design with just one PAF, one volume knob, no tone control. It’s very light, beautifully balanced—every string, every fret, all the way up the neck. It doesn’t have a lot of tonal character of its own, so it lets my fingers do the coloring. You can feel the fingerprints of Billy Gibbons on this guitar. It’s very Billy.”

“I looked at the stage and thought, ‘Whoa! I get it. You take all your influences and make your own thing. I’m gonna take all the things I love and find my way.’”

Addressing his role as the collector, “or acquirer,” as he says, some pieces have quite a history. “I haven’t gone out specifically thinking, ‘I’m missing this from the collection.’ I feel really lucky to have a couple of very special guitars. I got Waylon Jennings’ guitar in an auction. It was one he had all through the ’70s, wrapped in the leather and the whole thing. In the ’80s, he gave it to Reggie Young, who owned it for 25 years or so and eventually put it up for auction. My wife wanted to give it to me for my birthday. I was trying to bid on it, and she made sure that I couldn’t get registered! When it arrived, I discovered it’s a 1950 Broadcaster—which is insane. I had no idea. I just wanted it because I’m a massive Waylon fan, and I couldn’t bear the thought of that guitar disappearing overseas under somebody’s bed, when it should be played.

“I also have a 1951 Nocaster, which used to belong to Tom Keifer in Cinderella. It’s the best Telecaster I’ve ever played, hands down. It has the loudest, most ferocious pickup, and the wood is amazing.”

YouTube

Urban plays a Gibson SG here at the 2023 CMT Music Awards. Wait until the end to see him show off his shred abilities.

Other favorites include “a first-year Strat, ’54, that I love, and a ’58 goldtop. I also own a ’58 ’burst, but prefer the goldtop; it’s just a bit more spanky and lively. I feel abundantly blessed with the guitars I’ve been able to own and play. And I think every guitar should be played, literally. There’s no guitar that’s too precious to be played.”

Speaking of precious, there are also a few Dumble amps that elicit “oohs” and “aahs.” “Around 2008, John Mayer had a few of them, and he wanted to part with this particular Overdrive Special head. When he told me the price, I said, ‘That sounds ludicrous.’ He said, ‘How much is your most expensive guitar?’ It was three times the value of the amp. He said, ‘So that’s one guitar. What amp are you plugging all these expensive guitars into?’ I was like, ‘Sold. I guess when you look at it that way.’ It’s just glorious. It actually highlighted some limitations in some guitars I never noticed before.”

“It’s just glorious. It actually highlighted some limitations in some guitars I never noticed before.”

Keith also developed a relationship with the late Alexander Dumble. “We emailed back and forth, a lot of just life stuff and the beautifully eccentric stuff he was known for. His vocabulary was as interesting as his tubes and harmonic understanding. My one regret is that he invited me out to the ranch many times, and I was never able to go. Right now, my main amp is an Overdrive Reverb that also used to belong to John when he was doing the John Mayer Trio. I got it years later. And I have an Odyssey, which was Alexander’s personal bass amp that he built for himself. I sent all the details to him, and he said, ‘Yeah, that’s my amp.’”

The gearhead in Keith doesn’t even mind minutiae like picks and strings. “I’ve never held picks with the pointy bit hitting the string. I have custom picks that D’Addario makes for me. They have little grippy ridges like on Dunlops and Hercos, but I have that section just placed in one corner. I can use a little bit of it on the string, or I can flip it over. During the pandemic, I decided to go down a couple of string gauges. I was getting comfortable on .009s, and I thought, ‘Great. I’ve lightened up my playing.’ Then the very first gig, I was bending the crap out of them. So I went to .010s, except for a couple of guitars that are .011s.”

As with his best albums, High is song-oriented; thus, solos are short and economical. “Growing up, I listened to songs where the guitar was just in support of that song,” he reasons. “If the song needs a two-bar break, and then you want to hear the next vocal section, that’s what it needs. If it sounds like it needs a longer guitar section, then that’s what it needs. There’s even a track called ‘Love Is Hard’ that doesn’t have any solo. It’s the first thing I’ve ever recorded in my life where I literally don’t play one instrument. Eren Cannata co-wrote it [with Shane McAnally and Justin Tranter], and I really loved the demo with him playing all the instruments. I loved it so much I just went with his acoustic guitar. I’m that much in service of the song.”

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)