|

You started playing guitar when you were 6 years old, right?

Yes. I was a little kid playing guitar, following Peter, Paul and Mary, the New Christy Minstrels, and the Kingston Trio. And I was glued to the television whenever I saw Tommy Smothers playing his big Guild dreadnought. I was just fascinated by guitar. I don’t remember even thinking about doing anything else my entire life—that was it! When I was 6, I knew I was going to spend the rest of my life mastering this instrument. I’m not kidding you, I remember going to bed and having my guitar lying next to me. Especially if I got a new one, I did not want to put it down.

I’ve been there.

I’m still there. I build in batches, so I’ll build a batch of 16 in one group, and when I get done with them, each night I’ll take one home and I’ll sit on my couch and hug it and play it and kind of fiddle with it, just looking for any little thing I can tweak before I send it off. Man, I’m like a little kid.

What made you choose lutherie over a career playing guitar?

I bought into a guitar shop when I was 21, so for five years I was doing guitar repairs. When I was a little kid, and all through my formative years, the first thing I’d do when I got a guitar was take it apart to see how it worked. Then I’d put it back together, fix this, tweak that. I started doing repairs for my customers—and I had all these guitars to work on—so I learned to be a luthier by hands-on training, trial and error, doing it over and over again. So it was on-the-job training that got me interested in lutherie. When I was 26, I was so tired of playing guitar for a living. I didn’t want to play in another restaurant. I really lost the bug for that. So I decided I’d call Dick Boak at Martin—because he’d been sending me parts for my repairs—and ask him to send me all the parts for a guitar. I put together my first 10 guitars from what were basically Martin kits, which you can still buy from Martin today. And when I finished that first guitar, I was so surprised at how well it turned out that I put it in my store and sold it. After I got up to eight or 10, I figured it was time to go on to getting the wood and cutting it myself. So I got all the saws and planers and jointers and sanders and stuff, started building four at a time, six at a time, eight at a time. Within 15 years, I was doing 46 at a time, all by myself in my workshop. I’m down to about 30 a year now, because I’m getting older and slower and busier with life. When you’re 26 and single, you work all night and nobody comes looking for you.

|

So you started with steel-string guitars?

I did. Even though I’d studied classical guitar for many years and loved the sound of nylon strings, my first entry into guitar building was with steel-string acoustics. And after about 20 or 30 flattops, I started building classicals, too, because they’re pretty easy to do. If you can build a steel-string, you can build a nylon-string—it’s not that different. But the steel-string market is so much bigger, so it’s easier to sell a flattop than a classical.

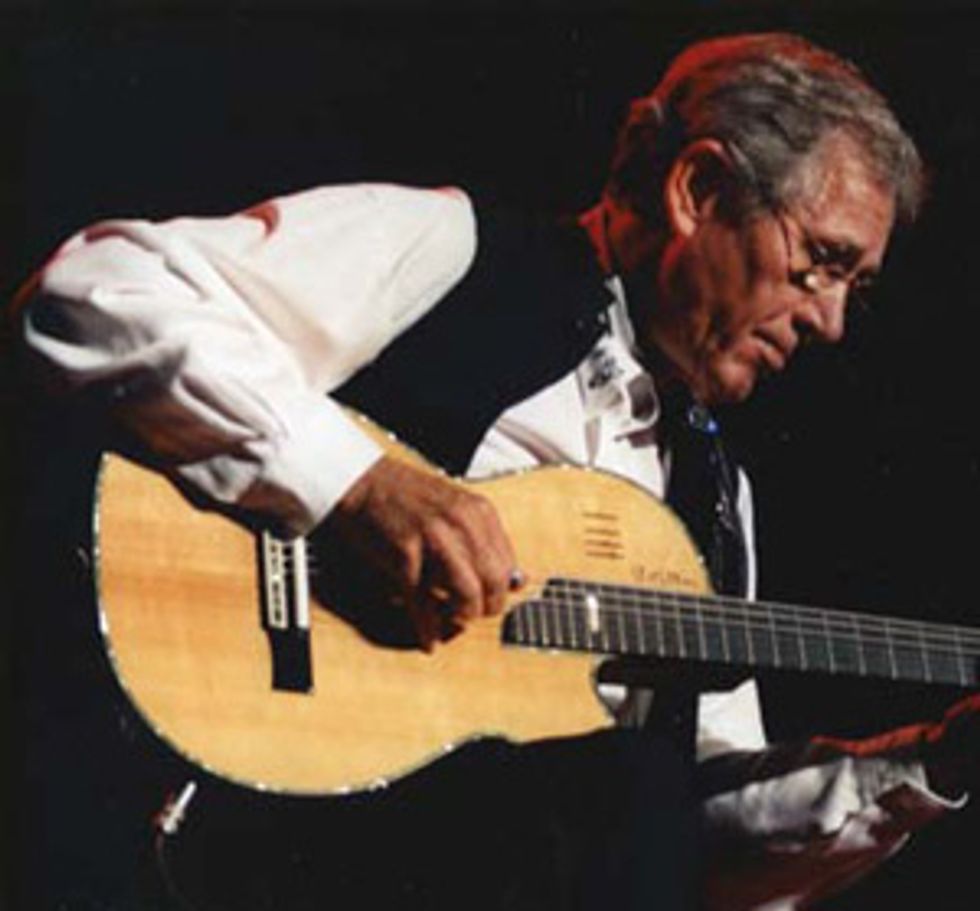

I got up to about 80 guitars and then went in the direction of the nylon-string electric (NSE) guitar, because I really love nylon-string guitars. I love to play them, I love the way they sound. And I thought the amplified part of it was fascinating: Plug a nylon-string into an amp, and you don’t turn it up loud, but you can turn it up to where you can be heard. So that’s when I met Chet and—bang—the rest is history.

Chet Atkins took one of the guitars you made for him to Gibson, and they started building those guitars there.

That’s the way it happened with Chet when he found a guitar maker he liked, because Chet was always affiliated with a guitar company. He started with Gibson in the ’80s, so from 1980 on it had to be a Gibson. When he found a guitar he really liked, he would just have Gibson make a replica of that guitar and add it to the Chet Atkins line. When I’d go to Nashville, I’d drop by Chet’s office and fix guitars for him, and we became friends. I came up with a design for a hollow, nylon-string electric with a thin, classically braced top and no soundhole. It was good for standing up and playing with a strap, and that was exactly what Chet was looking for. He was looking for an NSE that had two things: He wanted more of an acoustic sound, which we achieved by making it hollow and bracing it like a classical guitar, and it had to be lighter, because the Chet Atkins model he’d been using for 10 years was very heavy. It was solid wood—it weighed the same as a Les Paul.

When he saw my NSE, he said, “Man, this is fantastic. I want you to make me one just like this, but I want you to use my pickup and preamp.” Which was Gibson stuff. I didn’t realize at the time he already had it in his mind that he was going to have Gibson make this guitar. So I made him one, and by golly the first day he got it, he went down to Gibson. I got a call from Mike Voltz at Gibson saying, “Well, Chet just ran in here with this guitar and he wants us to add it to his line, so how do you do it?” So I proceeded to make them one that came apart, the top came off the body so you could see inside, the neck came off. They started making that instrument exactly like mine, and they did a pretty good job, too, for a factory. They were making it there in Nashville, and that factory really wasn’t geared up to make acoustic guitars.

How many guitars did you end up building for him?

I wound up making him four guitars over that 10-year period. I’d make him one and he’d play it a year or two, and then I’d entice him with something else, maybe a little more trim or abalone, and he’d say, “Yeah—I’d like to have one of those!” So I’d make him another one, and then I’d trade him. Now I’ve got two guitars that Chet Atkins used to own and play, and I’ve got lots of pictures of him playing them, so they’re kind of my retirement. Probably my kids will sell them at my funeral.

That must have been a huge boost for your business.

|

In the ’90s I made 300 NSE guitars, maybe a few more. I’m 61 now, so that was a good decade for me. I was buried with orders because of Chet. But I’m sure glad it was an instrument that I loved, because I wouldn’t want to have made 300 banjos during that time.

You made a 7-string guitar for Lenny Breau back in 1983, and that was kind of unheard of.

|

What were some of the challenges of designing the 7-string?

Well, in order to get the seventh string tuned up to a high A, we had to really experiment with the scale length, because there isn’t a string available that could tune up to the high A without breaking. So I shortened the scale length quite a bit. I experimented using a capo on the guitar and restringing it, moving the capo around and changing the gauge of the string to find just that certain scale length and string gauge that made the first string feel like it was the same tension as the other treble strings. The guitar had a 22 ¾"-scale length, which is very short. And the string was an .008, which is not all that thin, really. I think Lenny even used a .009 at times. The high A actually worked quite well.

What were some of the other distinguishing characteristics of that 7-string?

It was a classical guitar shape, and I incorporated a really deep cutaway. And Lenny wanted it heavy. It was solid mahogany. That thing weighed a ton. He wanted it to sustain—that was a big part of his sound. He’d do those harmonics and they’d just keep ringing like a bell, so he really liked the fact that the guitar was heavy and had the sustain it did.

What sorts of electronics did it have?

Seymour Duncan made custom pickups for it. There were no 7-string pickups at that time. The string spacing was the same as a classical guitar, and the pickups had to be fabricated so the pole pieces were directly under each string. Lenny also wanted those roller knobs that are turned sideways, like on a Fender Jazzmaster. Actually, I used Jazzmaster controls. Lenny would reach down to that volume control and move it back and forth to get a tremolo sound.

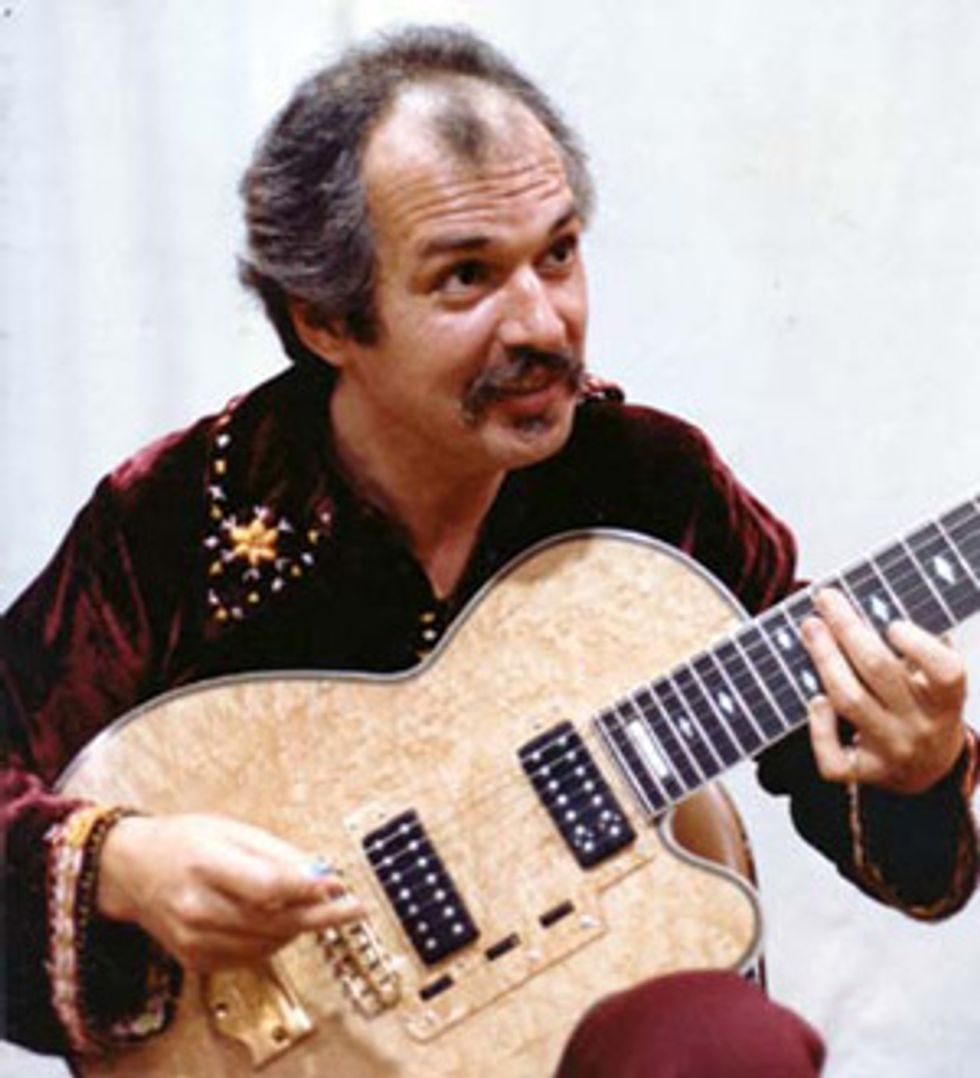

Tell me about the José Feliciano guitars.

He was my first celebrity guitar player. I met him back in the late ’70s at a party, and we started talking guitars. He said, “You know, Kirk, I want a nylon-string that’s got the body size of a dreadnought.” So I made him a guitar with a dreadnought-size body. It was a little more curvy, more like a jumbo, but with nylon strings, and he absolutely flipped out over it. He could get that huge bass. Other players who have played that guitar didn’t particularly care for how bass heavy it was, because the treble strings can suffer if you make the body too deep, but José didn’t have any trouble getting the melody to come out. He’s a really good, strong player.

What about the cutaway models he used to play?

The first three or four guitars I made him were that jumbo shape, but once he played one of my guitars that had my cutaway design, he began playing that model. The upper bout starts to come in toward the neck, kind of like a Telecaster, and then it swoops straight down into the cutaway. So the neck heel is not under the 12th fret where it normally is on a guitar—it’s much further down. It’s got really good access to the upper frets and it’s smooth to the touch, because there’s no heel back there. I wanted to get 14 frets free and clear of the body, 15 on the cutaway side, and there are two ways you can do that. You can just move the neck out two frets, and that’s what everybody does. They just scoot the neck out two frets so the body joins at the 14th fret, like a Martin D-28. But when you do that the bridge has to follow, it has to come up that same distance in order for the guitar to play in tune. So the bridge is no longer in the belly of the guitar, it’s closer to the soundhole, like a steelstring. But classical guitars are braced, built, and designed to have the bridge down in the belly of the guitar to make it sound good. Instead of moving the neck out and moving the bridge up closer to the soundhole, I left the neck where it was, left the bridge where it was—in the belly—and changed the upper body so the sides swoop down and join the neck at the 14th fret.

How does that 14-fret access change feel and playability?

When a classical player plays a guitar where the neck has been moved out, it feels funny because they’re used to having that 12th fret right under their nose. And extending the neck also throws off the guitar’s balance. So [my cutaway design] seemed pretty logical to me, and I’ve been doing it ever since. I’ve noticed that a couple of other makers are starting to do that, which I think is wonderful— the more the better. In fact, I’m surprised more cutaway guitars aren’t like that. I’m very proud of that design. Of course, I’ve never trademarked anything. It’s just a really good design and players seem to really like it.

Recently, you’ve started building carvedtop electric guitars.

I’ve always loved the carved top—it’s fascinating to me. I like the way it looks, and I’ve always wanted to build one, but I was too busy with NSE guitars. So a couple of years ago I thought I could carve a top and just put it on the same body my NSE has—the mahogany model, which is the hollowed out guitar like Chet played. And it works great. Carving the top is a lot of fun. It adds a third dimension to making a guitar top. If you’ve been making flattops all your life, to start off with an inch-thick piece of wood and end up with a violin-shaped top, that’s a lot harder than slapping some braces on a flat piece of wood. I’m not going to make too many of them, maybe six a year. I just made one for Paul Yandell, a singlepickup carved top electric (CTE).

How do CTEs differ from your other designs?

They have the same cutaway, and they have the neck pitched back like an archtop. They look just like a jazz guitar from the top, but they’re only 14 ¾” inches wide. Though they have the same body I use on the mahogany model NSE, I put the back panels in a different place to access the electronics.

Is there a standard pickup?

No. Paul Yandell had an old Ray Butts pickup he wanted on his guitar, and another guy that I just made one for wanted Seymour Duncan ’59s. I use Gibsons, Duncans, Fralins—anything you want.

|

So, what’s left for you to build now?

I love working with guys on their guitars, doing little things. Guitarists usually only have concepts or guidelines, they don’t have too many specific design ideas, so they let you mold them. Like the guitar I just finished for Paul has a special pickup on it, and the fretboard is designed so the bass strings are higher off the soundboard to prevent his thumpick from tapping the top. The pickup is a Prismatone II made by Sam Kennedy, and it’s a remake of an old pickup Chet Atkins and Jerry Reed used on their nylon-string guitars. It has huge bass and crystal-clear treble, and it’s Paul’s favorite nylonstring pickup. That guitar also has a special 24.9"-scale length that’s very short for a nylonstring and makes it really easy to play because the frets are closer together.

So I just enjoy building other people’s fantasy guitars. Email and digital photos have made things so much faster, too. A guitarist can think of a design, and then I’ll lay it out on my workbench and take a picture of it to send to them. Two seconds later, they’re looking at it. It’s fantastic. Technology has sped up the design process tremendously. I take pictures as I’m building the guitars and send them to the guys who ordered them. They love it. At the end of the day, I’ll send pictures to each of the customers, and they’ll put together a little scrapbook.

It’s kind of like getting an ultrasound image of your baby.

In fact, it takes about nine months to deliver a guitar. Depending on the model, my backlog is nine months to a year-and-a-half. Anyway, I hope to be just a little old man building 10 guitars a year, selling them for $50,000 apiece, living in my little house in Laguna Beach. I’ve got a cool little private workshop, about 800 square feet. I’ve got all my machines here. I can spray lacquer here. I’ve got a big flatscreen TV on the wall. It’s like that fantasy I had as a little kid, when I was so into artists and composers and I thought, “What a life! They just sit around and write music or paint—they don’t have to go to work everyday like my dad.” And now I’m doing exactly what I fantasized about. I’m not sure what I’m going to do when I grow up. they were so insistent on ordering