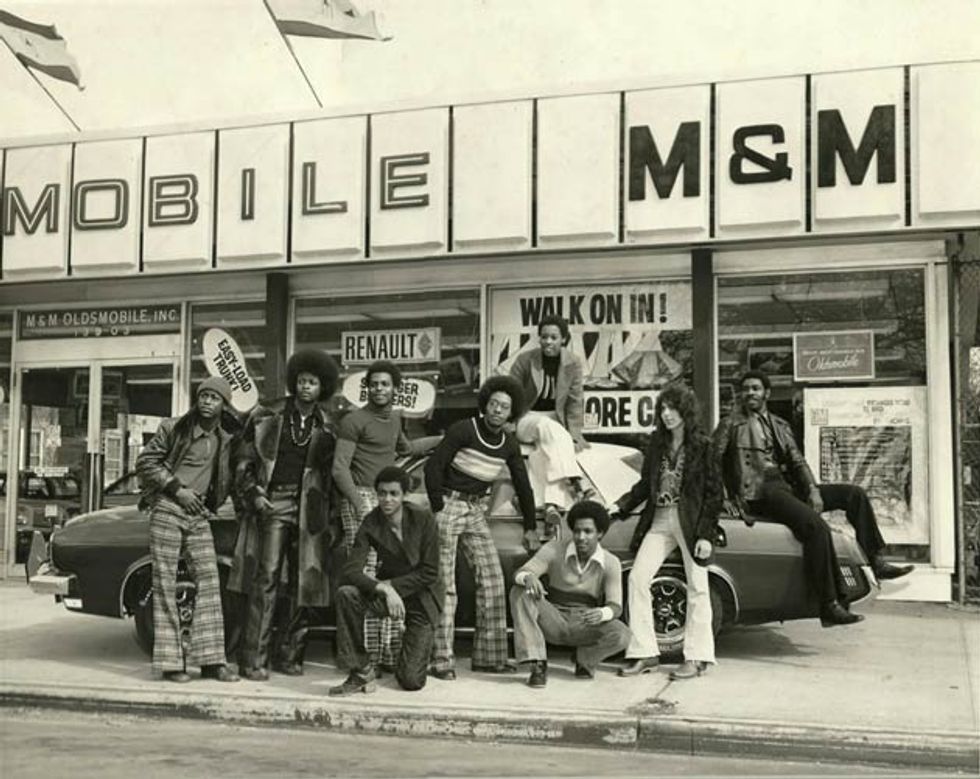

This rare, never-seen-before image was recently found by Joe Satriani’s management. Taken in 1973, the photo shows Satriani with the disco band he went on the road with for his first paid gig. Photo Credit Unknown / Joe Satriani Archives

Joe Satriani is one of those rare artists who has sold guitar instrumental albums in pop music quantities. His releases of the last two-and-a-half decades have become must-haves for more than one generation of guitarists. It’s fitting then that Sony’s Legacy Recordings has released a box set, Joe Satriani: The Complete Studio Recordings on 15 CDs, as well as in a limited edition USB drive housed in a metallic bust of the maestro.

Simultaneously comes the publication of an autobiographical history of those recordings: Strange Beautiful Music: A Musical Memoir (BenBella Books). As immediate and engaging as his music, the book details the creation of each studio record, and this makes it a perfect read while listening to the box set—or your own Satch collection.

Satriani grew up playing and teaching in Westbury, New York, later continuing that dual path in Berkeley, California. His teaching inspired a notable roster of students, including Steve Vai, Kirk Hammett, and Charlie Hunter, while his jaw-dropping playing won him the lead slot in a Bay Area band, The Squares, and introduced him to producer/engineer John Cuniberti. After the Squares’ dissolution, Cuniberti began recording Satriani’s instrumental vision, Not of This Earth.

By the second record, Surfing with the Alien, the guitarist had achieved something as scarce as a Yeti sighting: guitar instrumental radio hits. Virtuosic enough for guitar fans, Satch’s sound also proved accessible to folks with no interest in the whys and wherefores of whammy bars. With a style as rooted in the blues of Chuck Berry, Buddy Guy, and Billy Gibbons as in the guitar pyrotechnics of Eddie Van Halen and Jeff Beck, this 6-string wizard has conjured up platinum records and a loyal legion of fans.

Somehow Satriani still finds time for the occasional sideman gig with Mick Jagger or Deep Purple, G3 and G4 tours, and Chickenfoot, his ongoing side project with Van Halen alumni Sammy Hagar and Michael Anthony. He also made room in his schedule to tell PG about lessons learned from his teacher, jazz legend Lennie Tristano, playing with drum god Vinnie Colaiuta, and the fickleness of feedback.

What did you learn from Lennie Tristano that you still use in your music?

He discouraged me from living in the “subjunctive mode,” which he explained as a disease of suburban kids worrying about what they should, would, or could have played, while never playing what they want to play. He got me to not be judgmental—that is the essence of improvisation. To get there he insisted you learn everything completely and never make mistakes. If you made a mistake it was because you played without thinking, or before you were really committed—he had a million Zen reasons to explain why you screwed it up.

On a more practical side he said, “People use vibrato like a nervous twitch, without thinking about it. He asked, “Are you capable of playing a note and making it beautiful without doing anything to it?” I started rethinking the way I played, making the plain note as beautiful as possible, being more deliberate, using each kind of vibrato to create a specific feeling. Otherwise, it is like someone who puts salt on food before tasting it. There is magic in the way your finger hits the note; you would be surprised how many people, especially young students, make a horrible sound because they have never focused on that.

Did you study singers’ vibrato?

I wouldn’t say I studied them, but I grew up at a time when rock was a vehicle for vocals. The instrumentalists were secondary to the bands I really liked. Later, I began to appreciate classical, jazz, and every kind of instrumental music from around the world. That coincided with the Tristano lessons where he had me scat singing solos note for note. The idea was to make it part of your whole body by singing it, rather than just teaching your fingers how to play it. Every time I play a melody there is a vocal quality, but it isn’t like I set out to imitate singers.

The limited edition of Joe Satriani: The Complete Studio Recordings comes with a USB drive housed in a chrome dome of Satch’s head.

How has your playing evolved over the years?

That’s a good question. I have gotten a handle on a lot of the physical roadblocks. I realized through teaching that some people can play really fast, but don’t know what they are playing; others can’t play very fast, but have a good handle on what they are playing—they deliver quality phrases. Some people can’t play in tune but they can stretch their fingers. Some people can play the most complicated stuff but it sounds like sour milk when they play. Everyone has a set of pluses and minuses. The last tour I was marveling at the fact that I had been consistently taking care of these things decade after decade. It takes that long to relax enough to focus on all the aspects of playing.

Another side is your perception of yourself and what you think is necessary. When you listen to the box set you hear a very different musical personality from the first record to the later records. That personality affected how I tuned my amp, and how frenetically or subtly I chose to play. The albums are like diaries: You are letting people into your life. There were times when I wanted to ratchet it up, times when I wanted to chill out, and times when I got fascinated with a certain kind of sound, or had a particular ensemble around me.

When we remastered the records, John Cuniberti and I were struck by the change in production values—how primitive the early recordings were because of low budgets, but how much we accomplished with what we had. When we were doing Not of This Earth and Surfing with the Alien, there was a feeling that I might never get to record again [laughs]. I decided not to worry about being commercial and go against the grain. If I wanted to write a song in the Enigmatic mode and put the kick drum on the off beats, I would just do it.

When the legendary shredder recently switched from a 22- to a 24-fret neck, he was surprised to discover how tricky it was to get used to the extra two frets. Photo by Atlas Icons / Chris Schwegler.

Were you less able to experiment once you were established?

I became clearer about where I wanted to experiment. On the early records I was reacting against the small community I was working in. Before Alien was a success I was doing sessions. Any time I played in my style—the same one that later became popular with Alien—the producers would shut me down quite rudely: “Don’t play that, it’s terrible. Play like that other guy.” Within a year, those same people were calling and saying, “We would love you to come in and do that thing you did with the whammy bar and the wah-wah pedal.” I was happy to decline and say, “No, that’s mine. You can’t have it now.” I wasn’t getting more conservative, I was protective of the things that were special to the early records. I wanted to focus on the quality of the melody and it was difficult because my competition was all about athletics and big hair. But all you need is your audience saying, “We loved that song where you just played the melody,” to give you confidence to write 100 more songs that emphasize the melody over showmanship. Also, I was still playing Chuck Berry riffs, because I thought it was important to be true to my roots and influences.

Do you feel you can stray from what made you popular?

Absolutely. One of the mysteries of success is the “wrong” direction that artists take at any given time that make their audiences go, “What are you doing?” Your audience will fall in love with one set of songs because of when they heard them and what they were going through. You shouldn’t fight that—the randomness should give you the courage to strike out and try something different every time so you will connect with new people. The first two records were combining Kraftwerk or new wave-like drum machines with guitar. Later, the Extremist was me celebrating classic rock roots. It was the wrong record for what was happening in music at that time, but it ended up doubling my fan base. The [stripped down] Joe Satriani record and the techno record [Engines of Creation] might have resulted in a few fans saying, “I’ve had it with this guy,” but we gained far more than we lost because others were saying, “Finally, I can listen to this guy.” Glyn Johns [producer of Joe Satriani] once said to me, “It’s not your job to decide what people will like. It’s your job to play your guitar, so go out there and play your bloody guitar.”

Would it be correct to say the latest record, Unstoppable Momentum, harks back to Joe Satriani, in terms of the interaction with the live rhythm section?

Yeah, with Vinnie Colaiuta, Chris Chaney, and Mike Keneally, I took a chance they would be inspired by each other. There was true chemistry there and we took advantage of it by listening to a demo and then tracking within an hour or so. I gave everyone the opportunity to try something different on each take and after six or seven takes we had enormous variety to choose from. All of it was great—it was just a question of which feel we liked the best. It added an organic quality to the record. I wanted a full production, but I also wanted the feel to be very natural.

Joe Knows Gear

A look at Satch’s current rig, in his own words.

For this tour, my tech Mike Manning and I only brought out three guitars—the fewest since the Surfing with the Alien tour. We’d been bringing seven to nine instruments. This time I wanted to feel the smallest variation possible between guitars. My primary instruments are the Ibanez JS 2410 MCO [Muscle Car Orange] guitars, and a JS 2400 signed by Willie Nelson.

Once I started playing with Chickenfoot I began tuning down to Eb and using D’Addario .010–.046 sets. Before that I was using .009 sets at concert pitch. I’d been using Planet Waves heavy picks but recently ordered some extra heavies. For amps, I use my Marshall JVM410JS signature head. It’s comfortable having your own signature gear to plug into and wrap your fingers around. These days I have the most input into the gear, which makes for the least resistance.

I use my Vox Big Bad Wah at the beginning of the chain and my Vox Joe Satriani Time Machine delay at the end of the path. In between varies according to the song, but there is probably an Ibanez Flanger, a DigiTech Whammy pedal, and an Electro-Harmonix POG or Micro POG. Sometimes that’s it, or I might add a Voodoo Labs Proctavia. The Proctavia’s EQ curve is good for me, because I have a lot of low end in the amps.

Once I started working on the amp, I had to leave my signature Vox Ice 9 overdrive and Satchurator distortion at home. If I’m going to make an amp that has gain channels, I have to prove that they work. I did two tours using just the Marshall heads for overdrive. They have four channels with three modes each, so it was not like I was hurting for gain structure. The only thing in the amp effects loop is the delay and a Neunaber Technology Wet reverb pedal.

Gear has to be practical. I’ve had to play a variety of music over my career, so I’m not looking for a one-trick pony sound. It has to be flexible enough to work in many situations. If a guitar has a whammy bar, the tuning has to be impeccable. An amp has to sound good at low volume and high volume—it has to be switchable and be quiet. It needs all those things you’re required to have together whether you’re playing on television, in a small club, at a wedding or whatever. I’m always thinking about the working musician because that is how I started out.

What was it like working with Vinnie Colaiuta?

Some stuff, like the drum intro to “Jumpin’ Out” was a supreme Vinnie moment. Every take he would do a different but amazing fill. It had me thinking, “Wow—it’s too bad I can’t have seven of these.” [Laughs]. But even on “Shine on American Dreamer,” which is a straight rock song, he understood the emotion behind the song. He was masterful in how he hit, what he hit, and how he toyed with the time on the fills moving from the verses to the choruses to make them more dramatic. It was like he was tapping into my mind and soul.

Having done this for two decades, how do you stay inspired onstage?

Onstage the audience gives me the live energy that makes me want to play. If I could, I would do five-hour shows. This recent live unit—Marco Minnemann, Bryan Beller, and Mike Keneally—really freed me up. Though they are more technical players than I’ve played with before, they somehow made me more relaxed. I felt I played a little bit better because of the confidence coming from the rhythm section. We were playing 90 percent of the new record. It could be the new people, new material, or new equipment. The 24-fret JS guitar finally became more comfortable to play, which took some anxiety out of the live performance.

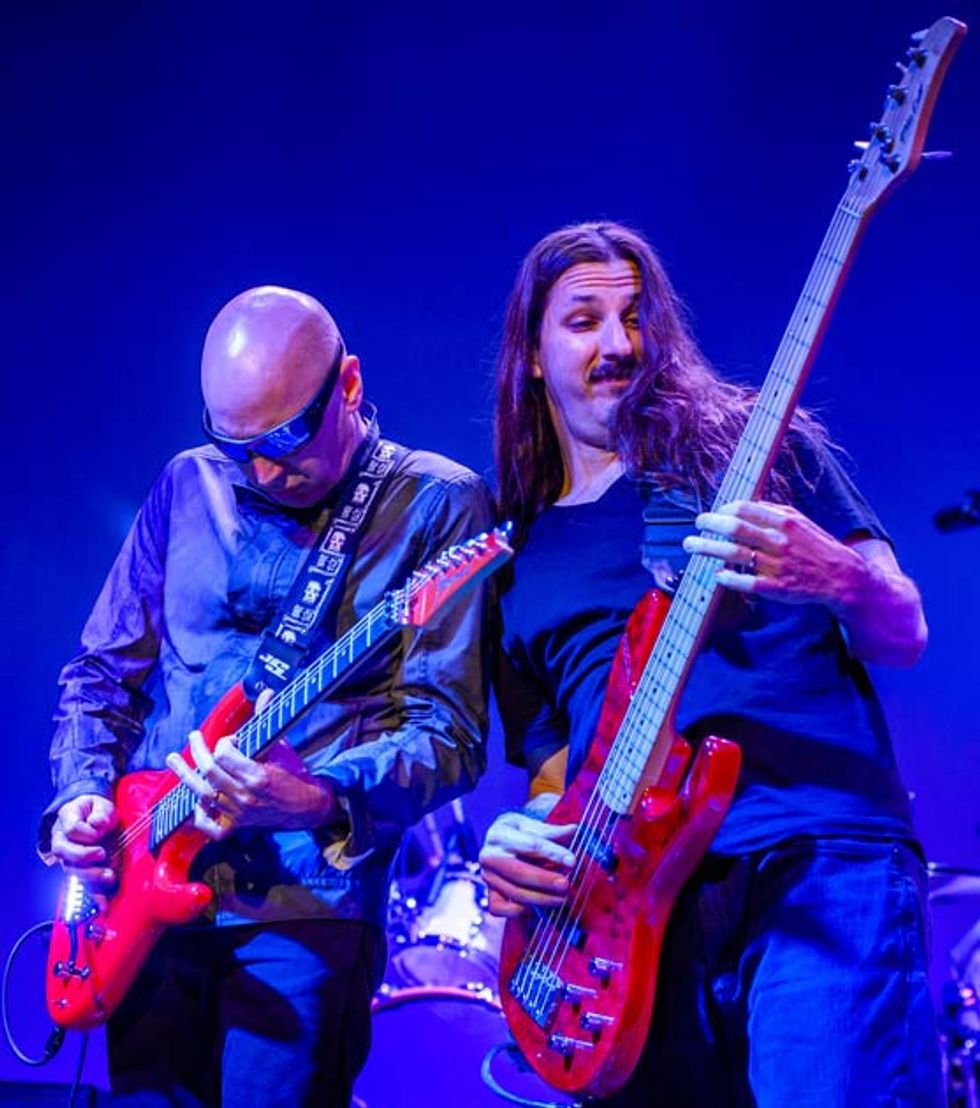

Satriani and Bryan Beller share a moment at the Macomb Music Theatre in Mt. Clemens, Michigan, in September 2013.

Photo by Atlas Icons / Chris Schwegler.

Was it hard to adjust to the extra two frets?

The last tour I switched between the 22 and 24 fret models. I thought it was comical that someone of my age and professionalism would be struggling because of two extra frets, but I would sometimes check in visually with the guitar and wonder, “Is that an A or a B?” I thought, “I can’t believe you spaced out like that. How long have you been playing guitar?” But starting with the Unstoppable Momentum tour I was completely comfortable with the 24 frets.

How much of the show is improvised?

In each song somebody gets an open spot. When we get to the end of “Unstoppable Momentum” we know it’s Marco’s spot to do whatever he wants. He is a great improviser and does different stuff every night. For my guitar solos, I like to identify the most important part, like in “Surfing with the Alien,” where the solo starts with a half-step trill up at C# when we modulate into the Phrygian Dominant mode. If you start that solo any other way it is a bit of a letdown, it’s like a part of the song’s composition. I make sure I hit those keystones. When I’m recording I’m looking for those wonderful moments that become the personality of that solo and song. The solo then belongs to that song—I don’t do that half-step trill in any other song. In “Jumpin’ In” the solo is mainly me having fun with pedals. I always use the same pedals—the octave unit, an extra delay, and the Whammy pedal—but the notes are always improvised.

How do the live arrangements differ from the record?

In the beginning, I had never fronted a band playing instrumental music before. We improvised a lot because we didn’t have that much material. There were some songs we couldn’t do because they were so keyboard or rhythm guitar heavy. I learned on those first two tours that it wasn’t as much about trying to recreate the album as trying to make the album better somehow. Every time I have a new album I identify the most essential parts. That might mean asking Mike Keneally to recreate what he did on the record, other times we might completely reinvent the tune for the stage.

Do you mark off places on the stage to guarantee feedback?

Oh, there is no guarantee. [Laughs.] If you’ve seen the Saturated movie, you know that. The director wanted me to stand in a particular place for the 3-D camera and as soon as we started the show I was getting the wrong feedback note. That said, since I don’t use in-ear monitors I have the wedges for feedback reinforcement.

YouTube It

Joe Satriani plays the title track from his 2013 album, Unstoppable Momentum, on his Ibanez JS2410 in Muscle Car Orange.

Why the book and retrospective now?

Because I was asked. Jake Brown wanted to do it along the lines of his others, which were interview style. We spent a year focusing only on the studio records, no live records or biographical stuff. When we found a publisher, they wanted it more first person and autobiographical. It took another year for me to write it as if I was talking to the reader.

I assume it will be available as an audio eBook?

Yes, we’re going to have music start off each chapter. We need to find the right voice, someone whose delivery doesn’t get in the way of the story—though I started out thinking it should be Nigel Tufnel [laughs]. Another thing that came up was video content. There is a lot of film John Cuniberti took back in 1989, like me laying down the solo for “Can’t Slow Down.” You would only be able to access it through the eBook.

The idea of the remastered box set started a little before the book. Once we got Sony and the publisher together it really started to happen. It took a long time, but that worked out well, as we were able to include Unstoppable Momentum in both the box set and book, which really brings it up to date. It was Sony’s idea to put the USB drive in a chrome head. It’s pretty weird when you hold a mold of your own head in your hands.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)