Close your eyes for a second and imagine your favorite electric guitar sound. What do you hear? Whether it’s a crystalline clean, a bulldog-growl crunch, or a hurricane of distortion, what do you envision?

Maybe you’re seeing the contours and finish of your guitar, the different pieces of wood that comprise the whole; a certain brand of strings ricocheting in microscopic variances; the woven grille in front of your amp’s speaker vibrating in a sonic windstorm; or perhaps your hands, both working in harmony to create exactly the right sound. It’s unlikely that when you think of your specific sonic nirvana, you picture the little bits of metal compounds that we call magnets.

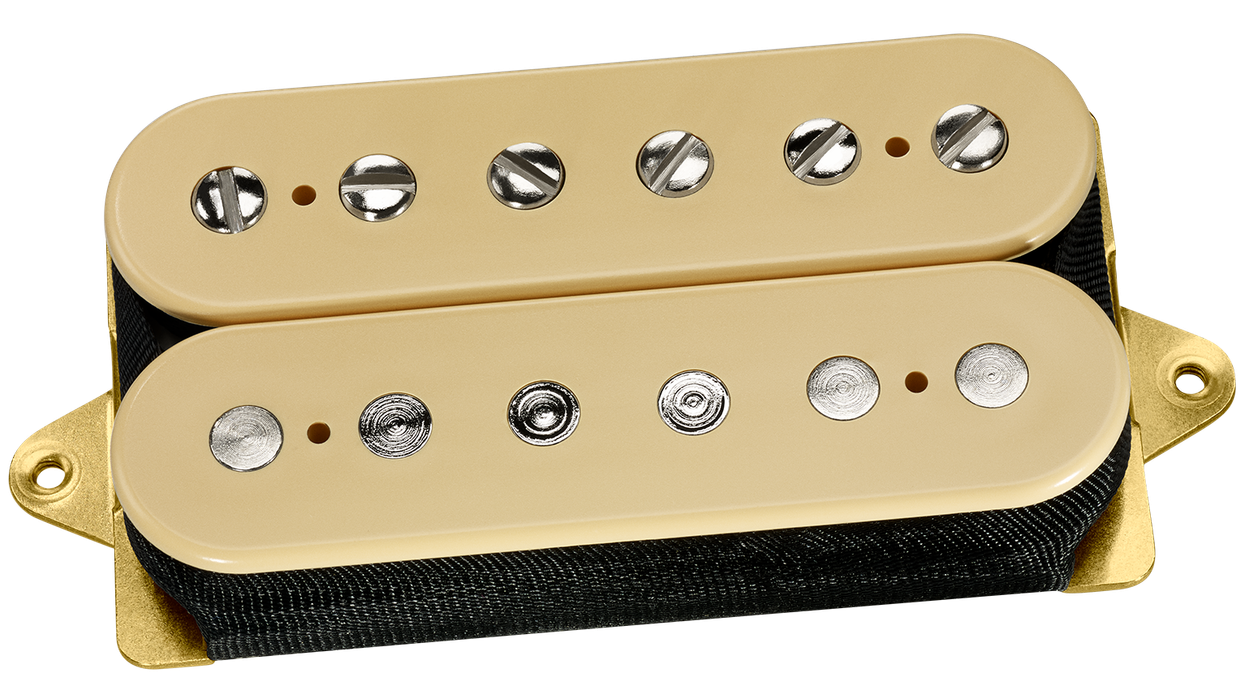

Yet it’s magnets which are the catalyst for the boundless wealth of sounds we can produce with modern electric guitars. Beginning with their first applications in guitar pickups in the early 1930s, magnets have evolved into one of the most critical factors in how we get the tones we love. They’ve bloomed from a rustic and rudimentary technology to a precise, booming cottage industry. And while dedicated tone hunters spend a lot of time discussing pickups, the particulars of the cylinders and strips of precision-machined magnetized materials that give each pickup its tonal signature aren’t often in the spotlight.

These mysterious bits of earth elements and their invisible force fields—the strengths of which are measured in a unit called a Gauss—breathe life into everything from hushed fingerstyle jazz acrobatics to industrial-grade doom-metal sludge. So how do we know what magnets can help achieve which tones? We need to understand some science, for sure. But we also need to know the history that created the pickup magnets we know and love.

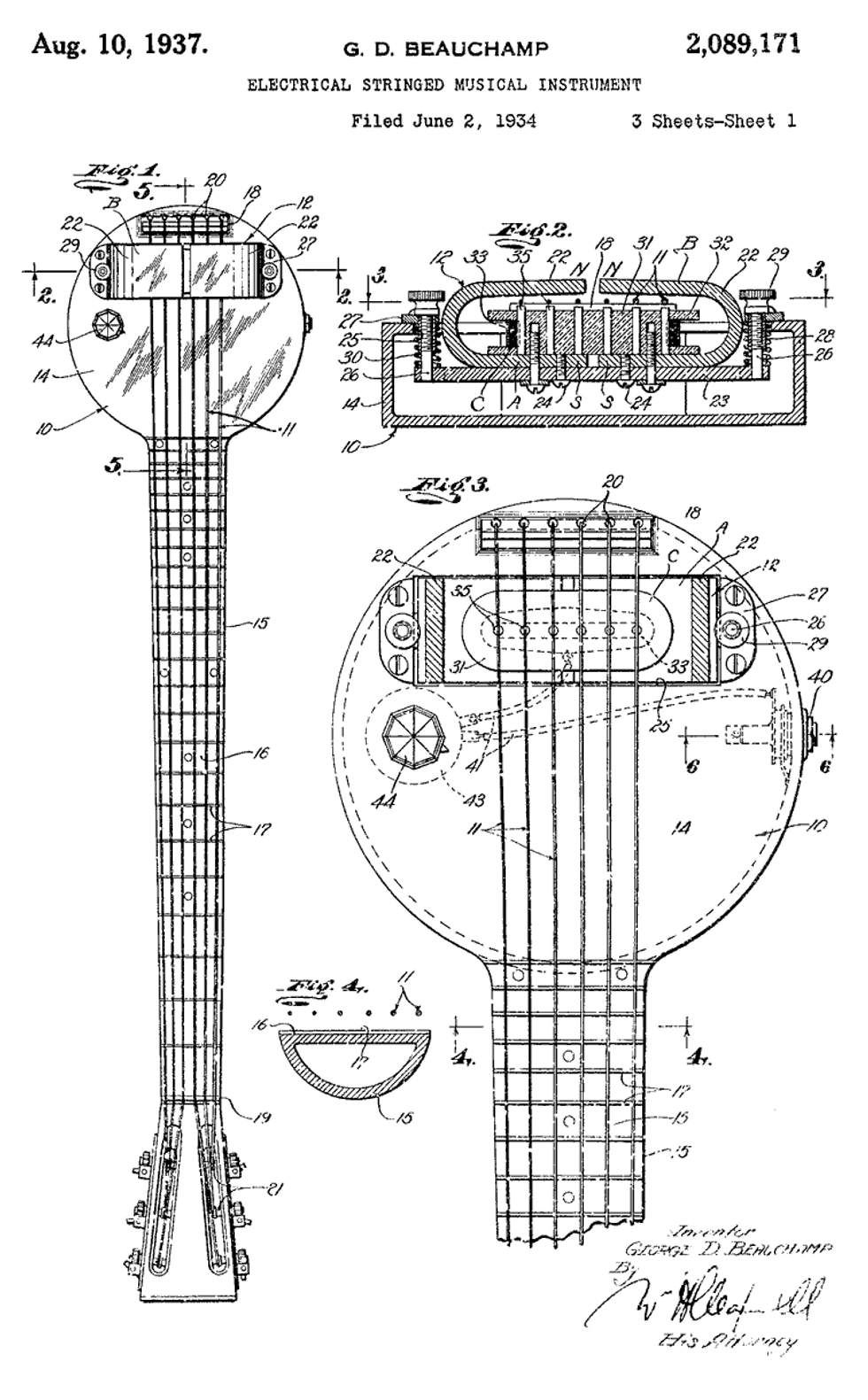

This blueprint, filed along with the patent application in 1934, demonstrates the A-22’s ingenuity, and the pickup magnet’s configuration.

A History of Attraction

The very first electric guitar pickups, circa 1931, probably wouldn’t be much fun to play through. They were created by American inventor George Beauchamp and Swiss-American engineer Adolph Rickenbacker, who together founded—you guessed it—the Rickenbacker company, first named Ro-Pat-In, then Rickenbacher, before they settled on their final designation. The duo built the Electro A-22, nicknamed the Frying Pan (take a quick look and it’s fairly easy to guess why), an aluminum lap-steel guitar constructed to capitalize on the popularity of Hawaiian music at the time. It was the first stringed instrument to bear pickups.

The A-22’s chunky pickup magnet, crafted from an iron alloy with around 36 percent cobalt steel, was incredibly weak and unfocused. But it established a universal principle that shaped the future of the guitar: A magnet’s field can magnetize guitar strings, and together with a spool of wire, the magnets can generate enough output current to send to an amplification system. The basic process of capturing and amplifying sounds hasn’t changed much in the 90 years since Beauchamp and Rickenbacker slapped a big, magnetic rock on a guitar that looked like kitchenware, but the tools to accomplish it have.

“A lot of what Leo Fender did involved war surplus stuff in Southern California ’cause there was tons of it around for all the aircraft factories.”

Tim Shaw, chief engineer with Fender, has been building pickups for the past half century. He’s spent the last 27 years in various capacities with Fender, prior to which he ran research and development for Gibson, operated a repair shop, and helped Fishman establish their OEM pickup system. But before all of that, he learned how to make pickups from Bill Lawrence, the German-American builder who changed Gibson’s trajectory in the late 1960s. Lawrence, says Shaw, was the real deal—he had a coil-winder in the trunk of his Cadillac, which was functionally the same as Leo Fender’s original winder. And he didn’t suffer fools.

“He was pretty crusty,” Shaw recalls. “He would cuss me out in Polish and German. But I learned a tremendous amount from him. He would explain these things very clearly, very logically, in a very German way. It was priceless.” Lawrence, who came to pickup design with a respectable music career and a background in physics, instructed Shaw on which magnets to use, and how many turns of what gauge wire were required for certain sounds.

Tim Shaw has been building pickups for nearly half a century. When it comes to magnet materials, he says guitarists stick to what they know.

Perhaps the most important lesson that Lawrence taught Shaw was that he shouldn’t get into the pickup business to be an artist. “Most of the time, you’re not making something which never was,” says Shaw. “You’re working with an established vocabulary. So much of what we do is ‘in the style of.’” The reality of magnet selection and pickup design, says Shaw, is that there isn’t a whole lot of room for experimentation. “The big fight with all of this is guitar players,” he says. “There’s a conservatism: We know what we like, we play what we’ve played. If you have something that’s interesting but radically different, there aren’t as many people as you would like to think who will just a priori accept that and go for it. I could literally do a pickup brand from all the stuff that people didn’t want.”

Instead, when he designs pickups, Shaw follows the same three principles that guide musical instrument production: They have to give us the sound we want, at the volume we have to play, and we have to want to play them. “If you don’t get all three of those things right,” says Shaw, “you’ve got a decorative wall hanging.”

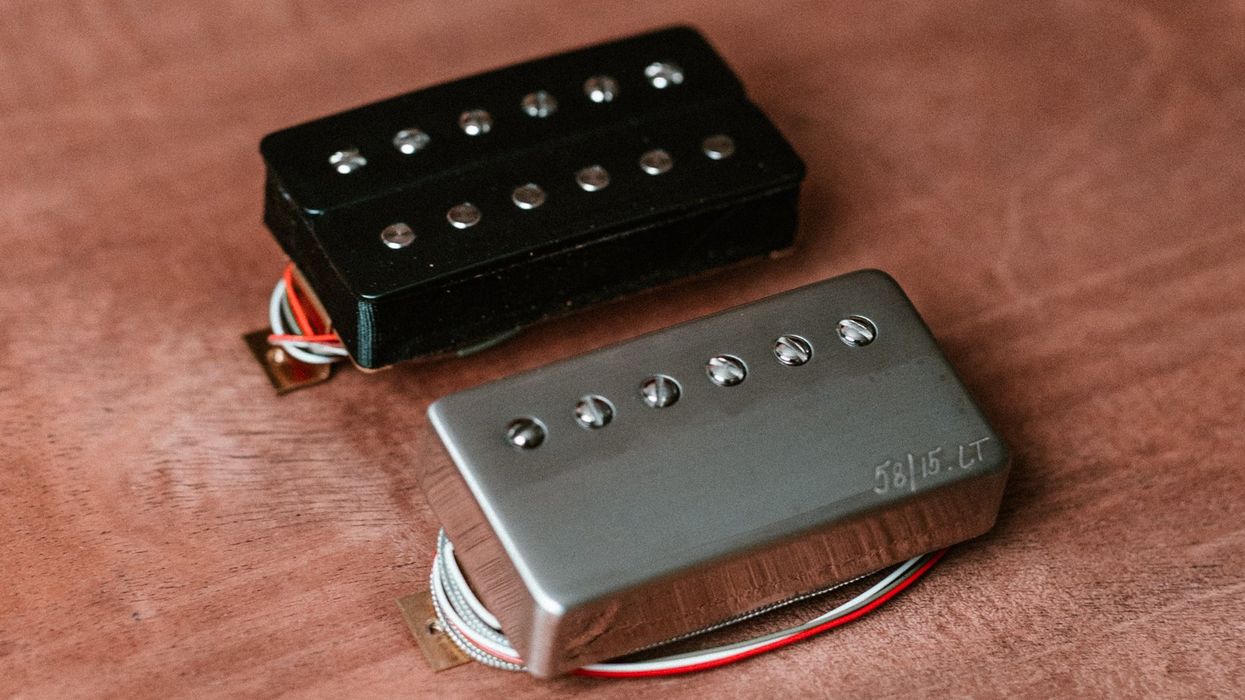

From alnico to neodymium, magnets have gotten stronger and changed how our electric guitar playing sounds and feels. They’ve radically altered how pickups themselves are designed and built—if a builder worked with the same design specs and material ratios for a ceramic-driven pickup as they did for an alnico-powered pickup, the result would probably be unbalanced at best.

Let’s look at the popular magnet materials that have been wired up by pickup designers over the last century. Along the way, we’ll dig into how their construction, physical composition, and magnetic properties change how our guitars sound.

Alnico Alloys

The first alnico alloy—aluminum (Al), nickel (Ni), and cobalt (Co), plus iron—emerged in the late 1930s. Since then, five different versions of the alnico magnet have grown in favor among pickup builders: alnicos 2, 3, 4, 5, and 8. The first four are the most common ones and can be used in both rod and bar form.

Alnico 3, which paradoxically contained no cobalt thanks to a Korean War-era embargo on the substance, is the least powerful, but it became the first go-to alnico alloy in Fender’s early electrics. I think a lot of what Leo Fender did involved war surplus stuff in Southern California cause there was tons of it around for all the aircraft factories,” says Shaw. “So he had access to a lot of alnico 3 rod material, which he got cut into lengths that made sense for him.” Gibson, meanwhile, was cutting it into bars to outfit their P-90 pickups.

Making alnico magnets was a nasty business. Shaw describes alnico factory lines as “14th-century-looking stuff,” where a massive ladle is filled with over 600 pounds of iron, cobalt, copper, and aluminum shot, heated to the materials’ respective melting points, then poured into molds. But the magnets that came out often varied massively in composition and sound. Aluminum has a much lower melting point than its ladle-mates, and as it boiled off while waiting for the others to melt, the mixture’s composition would change. One would need to continue adding aluminum through the process to maintain the correct ratios. The magnets made on a Wednesday morning shift could be totally different from the ones poured the night before, explains Shaw. “That’s one of the explanations for why vintage pickups do not all sound the same,” he notes.

Technically speaking, alnico 2s are slightly more powerful than 3s, with 4s and 5s topping both for magnetic strength, and, therefore, output. In terms of sonic characteristics, Shaw says the alnico 3s have the slowest attack, and the “warmest and woofiest” sound. Alnico 2 dials back that thick character a bit, while alnico 4, says Shaw, is sharp but “polite:” “It almost has a smirk to it,” he grins. Shaw describes alnico 5s as the boldest of the bunch—the magnet that says, “Yeah, we’re gonna go for it, guys.” Fender P-basses were initially outfitted with alnico 3s until Leo Fender realized it tends toward what Shaw dubs a “drunken elephants dancing” tonality. He swapped in alnico 5s around the mid 1950s for their brighter, harder sounding magnets, a decision that cemented the brand’s signature sound. “Leo was all about attack,” observes Shaw.

The high-output alnico 8s are the strongest of their alloy class thanks to their inclusion of titanium. The 8s are so powerful that they can pull strings out of their arc in the right conditions: if you raise your neck pickup too high and play above the 12th fret, you might hear weird tones thanks to this phenomenon.

Ceramics

Like Leo Fender favoring cheap metals that he could get in bulk nearby, other regional pickup-design characteristics—and the sounds they encouraged—can also be traced back to geographical and industrial particulars. The former Chicago-based discount guitar manufacturer Harmony turned to Toledo, Ohio’s Rowe Industries and lead designer Harry DeArmond to find cheap pickup materials. In response to booming demand, Rowe was turning out rubberized ferrite magnets—the kind you’d find on your grandparents’ refrigerators—which Harmony popped into their jazz guitar pickups. These are the magnets that power the infamous gold-foil pickup.

By the early ’70s, barium and strontium ferrites (compounds which are “deadly poison to be around,” notes Shaw) were developed. These were much stronger than their rubberized ferrite predecessors, and cost far less to produce than alnico alloys thanks to the elimination of the need for smelting. Instead, they’re created through a compacting and heating process called powder metallurgy. They became popular across a huge spread of sectors, and before long, pickup designers like Rick Turner at California manufacturer Alembic Inc. began to recognize that these stronger, harder ferrites—now known as ceramics—could be applied in guitars.

“I could design a whole guitar around a magnet if I wanted.”

Under Bill Lawrence’s direction, Gibson began employing these bar-shaped ceramics in humbuckers, which lent their guitars a sharper attack that paired well with players’ growing interest in heavier overdrive and gain. Lawrence’s Super Humbuckers were the first major pickups produced with ceramics. To deal with unwanted feedback and to prevent their covers from vibrating, designers like Lawrence epoxy-potted the pickups.

Ceramics found in pickups are usually ceramic 8s, which on a Gauss meter typically clock in at around twice the power of an alnico 4. Thanks to their magnetic flux at the pole pieces, ceramic 8s grab the strings quicker than regular humbuckers, and deliver a brighter, harder attack. These qualities make them especially well-suited for high-gain guitar playing without sacrificing definition, and builders like EMG and players like Kirk Hammett have gravitated toward them since.

Cunife

The original patents for the cunife magnets, made from copper, nickel, and iron, date back to the late 1930s, at which time there was a growing need for a magnetic material with high ductility—the ability to be manipulated and reshaped without breaking. Cunife magnets of all different shapes were used in speedometers, altimeters, and tachometers (a function that lent them the nickname ‘tach-rod’).

“The big fight with all of this is guitar players. There’s a conservatism: we know what we like, we play what we’ve played.”

By the early 1970s, Fender was looking for a response to Gibson’s humbucking pickups. Seth Lover, who created the humbucker for Gibson before switching teams to Fender, came up with a unique opponent: the wide-range cunife pickup. The cunife magnet’s ductility meant that, unlike alnico, it could be machined into screw-like pole pieces like the humbucker’s steel slugs, and Lover discovered that when paired with more winds of wire, cunife’s higher inductance translated to more bottom end and low mids without sacrificing Fender’s classic high-end clarity. By the end of the decade, though, digital appliances were becoming more prevalent, so cunife’s industrial and consumer utility was swept away and production lines for the magnet vanished. Pickup builders like Lover realized there wouldn’t be any material left to build with, so it was abandoned in most pickups—until a few years ago.

Tim Shaw managed to track down some incredibly expensive cunife magnets to design a new, revitalized line of vintage-correct wide range cunife pickups for Fender. But building with the magnet was tricky—he had to balance the physical and aesthetic demands with the cunife magnet’s needs—namely, a larger wire coil. “It could only be so tall if I wanted to fit it in a vintage guitar,” says Shaw. “I could design a whole guitar around a magnet if I wanted, but what I ended up doing from a practical standpoint was finding something that worked inside that form factor.”

Cunife-loaded pickups tend to strike a balance between humbuckers and single-coils: As their trademark name implies, they capture a wider range of frequencies than your average Strat pickup, but they don’t quite dive to Les Paul humbucker depths on the low end.

Neodymiums are the strongest pickup magnets around, and builders like Q-tuner have pioneered eye-catching new designs around the material.

Neodymium

Neodymium is a powerful, expensive rare-earth metal that’s still relatively rare to find in guitar pickups. Commonly used in iPhone speakers, neodymium’s strong magnetic field means that its application in pickups looks different than other magnets—thanks to its high output, only a small amount is required, which impacts how it’s inserted and oriented in a pickup context. Proponents celebrate the magnet’s ability to capture a wide dynamic range with detail and sensitivity. Fishman fits their magnetic pickups with neodymium magnets, for example, and builder Q-tuner has been churning out eye-catching neodymium pickups for almost 30 years.

But while some pickups can be swapped out without much worry to achieve different tones, stronger materials like neodymium require a bit more engineering. For example, Shaw says it wouldn’t be wise to simply replace a Strat’s alnico pickups with neodymiums. “I have, and you wouldn’t like the way it sounded,” he says. “It’s bright, and very forceful. Insistent, if you will.”

DiMarzio Introduces Muscle T Pickups for Telecasters and Super PAF Ceramic

DiMarzio Introduces Muscle T Pickups for Telecasters and Super PAF Ceramic