You learned everything you need to know about guitar pickups in your 5th grade science class. Or at least 90 percent of what you need to know. Reflecting knowledge dating back a hundred years, a pickup’s electromagnetic principles are rudimentary and covered in every grade-school science book. However, the other 10 percent—how to implement those principles and apply them to an electric guitar to make you sound like the musical god or goddess you are—is what legends are made of. Let’s review the first 90 percent; we’ll stick close to the basics and explain how electromagnetic pickups work, in case you were absent from class that day.

To start, pickups are based on two separate but related principles: If you place a coil of wire near a magnet and induce a change in the magnetic field, electricity will be generated in the coil’s windings. Also, if you place a piece of non-magnetized ferrous metal near a magnet—a screw, nail, a paper clip, whatever—it too will become magnetic.

There’s a chronological sequence of where your guitar sound starts and finishes. The energy from your fingers and pick is transmitted to your guitar strings, which disturb the pickup’s magnetic field, thus affecting a coil of copper wire within the pickup and generating an AC signal that trails out from the two ends of the coil to connect to any tone and volume controls your guitar may have. From there the signal heads to your guitar’s output jack and instrument cable, through any pedals, and finally to your amp and speaker.

Every one of those stages will have a significant effect on the resulting tone. There is enough to discuss about this topic to fill a book—and in fact it has, many times. To begin to understand pickups, let’s look at those first few stages.

It All Starts With Strings

The first step in getting a pickup to generate any signal at all is to disturb the pickup’s magnetic field. Though electric guitar strings come in many varieties, they all share a common trait—the ability to affect a magnetic field as the string vibrates. Naturally, this means the strings need to be vibrating somewhere within that field. Depending on a pickup’s design, its magnetic field may span a small or wide area, and that’s good to keep in mind.

Because strings are responsible for a significant portion of an electric guitar’s sound, it makes little sense to compare the performance of different pickups until you’ve done your homework with strings. You’ll want to be familiar with the basics, which includes exploring the differences between lighter and heavier gauges, nickel-coated steel or pure nickel windings, roundwound or flatwound construction, and round or hex cores. Consider buying a handful of different types of strings made by different manufacturers and spending quality time with each set. There’s a reason manufacturers offer so many string choices, and a little experimentation can yield big dividends.

Tom Klukosky, whose “factory manager” title downplays his multi-functional role at DR Strings, points to three string-related variables that affect your sound: the string material, the winding technique used for the wound strings, and the string’s ability to vibrate. He points out that strings are the “singers,” the originators of your tone. If you don’t like the singer’s voice, changing the microphone isn’t going to help.

Strings disrupt the magnetic field by vibrating within it, and a string’s material affects the strength of this disruption. And with wound strings, this becomes a key consideration. Unlike nickel-plated steel, pure nickel doesn’t affect the magnetic field. Neither does stainless steel—the core is doing the work.

In choosing strings, don’t simply go by what you might hear others say. For instance, strings wound with pure nickel have a reputation for “warming up” your sound. However, Klukosky prefers them because the plain (unwound) strings sound brighter in comparison to those wound with pure nickel, and this shifts the overall tonal balance toward the treble strings.

Location, Location, Location

String vibration is greater in the area of the neck pickup and less towards the bridge. The difference in vibration along its length means that different pickup positions result in readily noticeable variations in tone. If you ever get a chance to tinker with an archtop equipped with a floating pickup that can be readily repositioned between the bridge and the neck—such as the classic DeArmond Rhythm Chief—you’ll see how sensitive the positioning can be. If your guitar has multiple pickups, their positions (neck, middle, or bridge) will be taken into account by their maker.

While two or more pickups might seem ideal in terms of tonal variety, these extra colors come at a cost. One advantage of a bridge-pickup-only guitar is the absence of magnetic pull on the strings that a neck pickup would exert. This pull can impede string vibration. It’s one reason why the single-pickup Fender Esquire, for example, has its fans. Mod Garage author Dirk Wacker put it nicely in PG’s April 2012 issue: “The Esquire is not a Telecaster with a missing neck pickup, but rather a distinct model with its own sound.”

You can also do very well with just a neck pickup. Equipped with only a neck pickup, my 1955 Gretsch Streamliner archtop gets a lot of use. The absence of a bridge pickup, which would otherwise add mass near the bridge, allows the top to react more freely around this critical area, and this gives the guitar a nice woody tone.

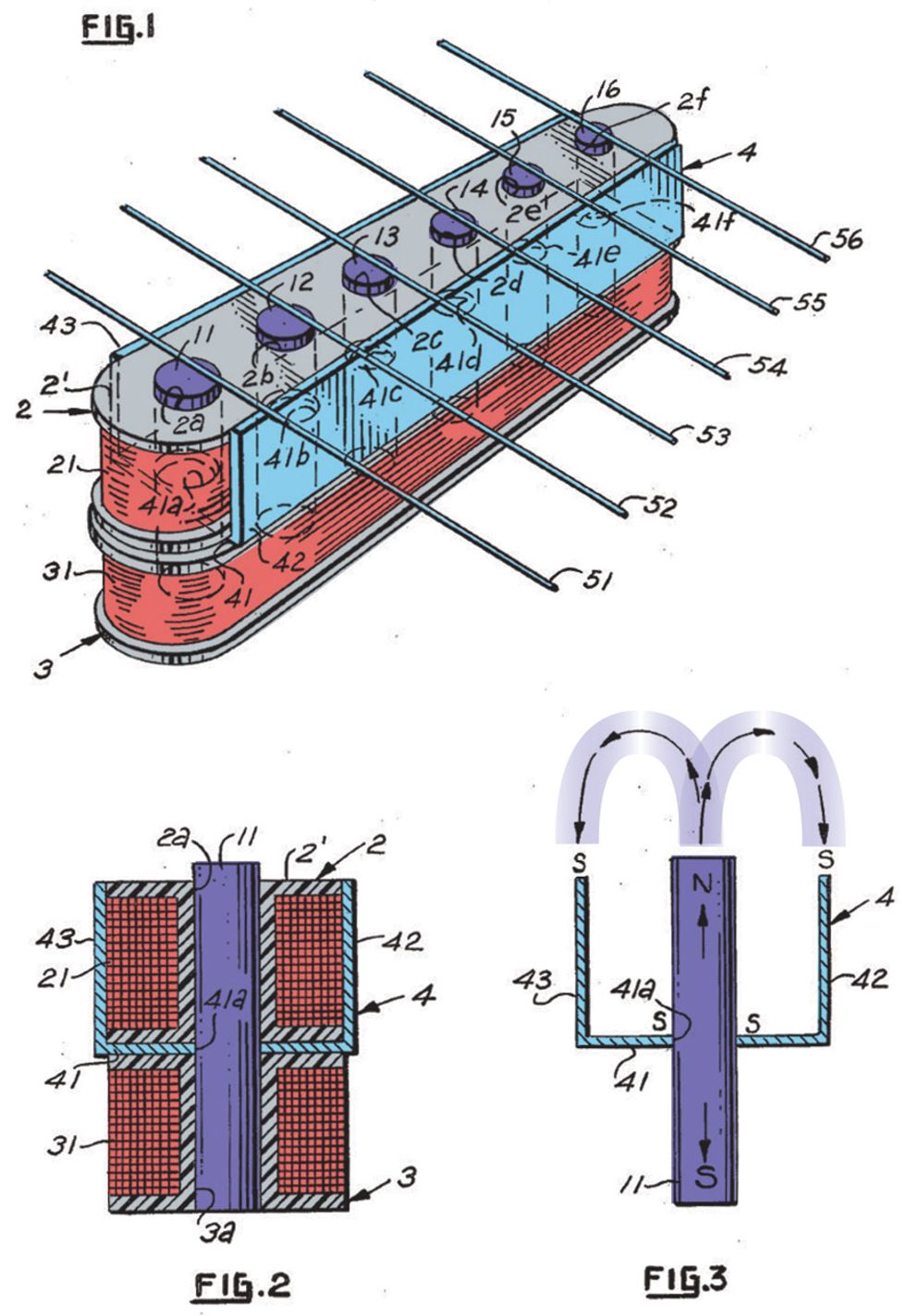

In evaluating pickups and related technology, just remember that a pickup is a sensor, and that the sound starts a few millimeters above it. Reinforcing that view, in the 1960s Gretsch referred to their pickups as “Electronic Guitar Heads,” borrowing the term “head” from tape recorders, which also rely on magnetic technology (Fig. 1).

Fig. 2 — Photo by Dan Formosa

Pickup Pole Pieces

A typical pickup may contain six individual magnet poles (often referred to as pole pieces). Or it may contain six steel poles that have become magnetized as a result of their proximity to a magnet lying within the pickup. Dissect some pickups and you will encounter variations on these basic themes, such as a steel blade that runs across the pickup beneath the strings.

Using magnets for poles and wrapping a coil around them is the most straightforward method of making a pickup, but this concept has a few limitations. If a magnet could be easily machined, pickup manufacturers would just turn them into screws to allow easy height adjustment. But they can’t. Or, more accurately, it has been tried, but abandoned.

other technical specification.

Therefore on a typical Stratocaster or Telecaster pickup, the individual magnet poles are not adjustable. The pickup may come from the factory with all poles set at an even height, or the heights may be staggered to anticipate the preferred string balance, as shown in Fig. 2. But the only way to adjust a pole on a traditional Fender pickup is to raise all of them at once by raising the pickup itself.

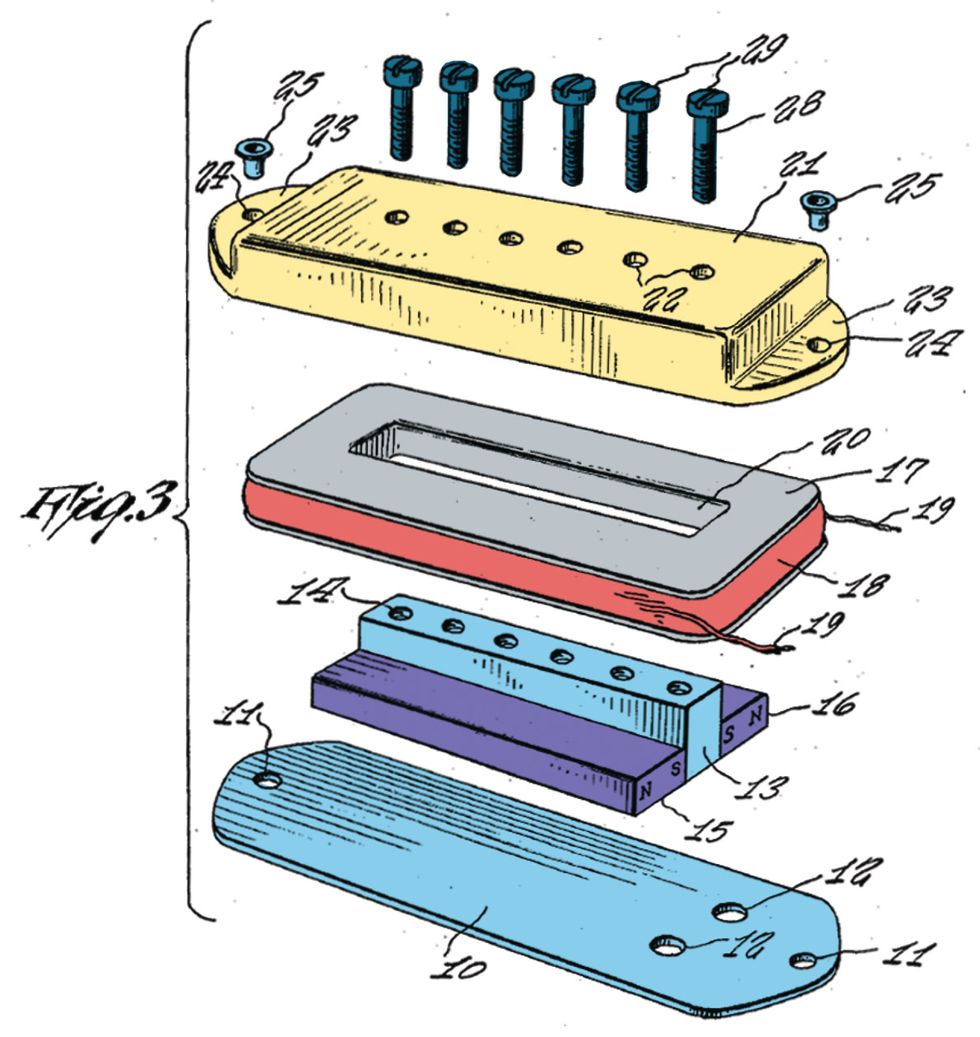

Harry DeArmond solved this problem with the DeArmond 2000 (aka Dynasonic), a pickup that employed a rather complex mechanism. Six small slotted screws, visible from the top, connect to adjoining magnetic poles, secured from within by teardrop-shaped brass rings (Fig. 3). Each pole has a spring that allows it to move up and down, so you can turn the screw to adjusts the pole height. Gibson’s “staple” pickup, developed circa 1954, follows a similar model.

Fig. 3 — Photo by Dan Formosa

Why bother staggering the pole heights? It’s simple: Different string types and gauges will perform differently. Your 2nd string will have approximately 50 percent more metal reacting with the pickup than your 1st string. An unwound 3rd string will have approximately three times as much. And although the amount of steel will be a contributing factor, it’s not the whole story. A .016 plain 3rd string isn’t going to vibrate the same way a .009 1st string vibrates. To ensure good string-to-string balance, it’s helpful to have height-adjustable poles.

Fig. 4 — Photo by Dan Formosa

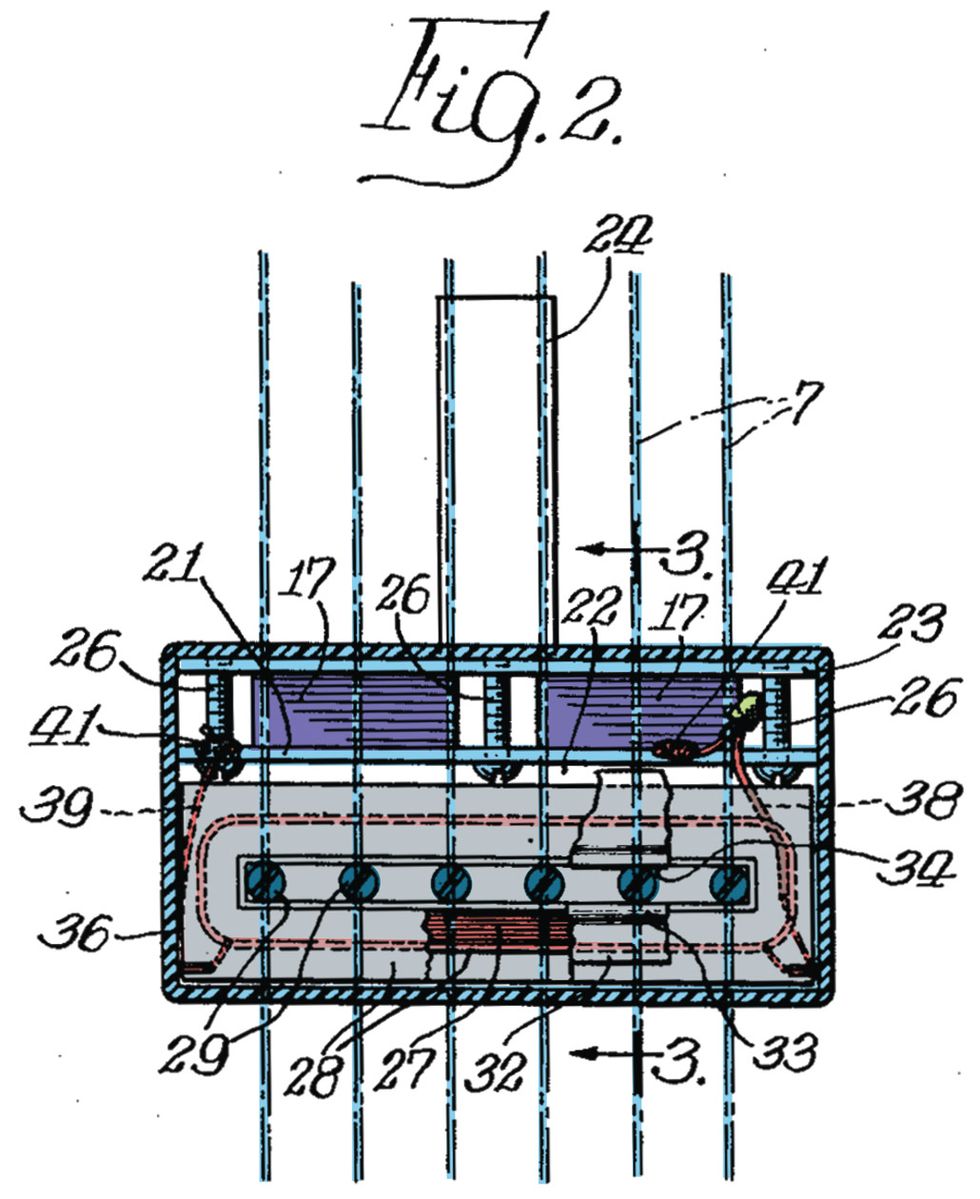

DeArmond’s adjustable mechanism is beautifully intricate, but there’s an alternative solution: use steel screws. Designing a pickup so that portions of the steel screws are near a magnet allows the screws to act as magnets that can easily be individually adjusted. Problem solved. Fig. 4 shows a single-coil P-90 pickup with two bar magnets and adjustable steel screws for poles. This design was patented by Charles F. Shultz in 1959.

In the early days of electric guitar, adjustable poles were more of a necessity than they are now. As pickup maker Curtis Novak points out, strings made today are much better balanced than strings were in the past, so worry not—you and your pickups with non-adjustable-poles should get along just fine.

When tinkering with adjustable poles, don’t simply set them to be as high as possible. Raising a pole means you are placing its magnetic field up closer to a string. Any perceived improvement obtained by bringing a pole closer to a string may be offset by a decrease in sustain as the magnetic pull dampens the string’s vibration. It’s well worth spending time to experiment with different pickup and pole heights. Many guitar manufacturers and pickup makers offer charts showing optimal spacing between pickup pole pieces and their corresponding strings. This information is based on a lot of testing and research, so it’s a good idea to at least start with the recommended settings.

Fig. 5 — Photo courtesy of Seymour Duncan

The Coil

A coil, which typically surrounds the poles or the magnet, usually comprises 5,000 to 9,000 turns of super-fine copper wire. Fig. 5 shows the coil on a modern Strat-style pickup made by Seymour Duncan. Current manufacturing techniques automate the winding process, ensuring that the wraps are laid down evenly, and that the pickups coming out of the factory will sound identical. Pickups made in past decades were wound by hand, which meant less consistency in the number of windings and the evenness by which they were coiled. (Pickups made by hand today are similarly more variable, at least in some respects.) Does this inconsistency contribute to a more classic sound? It’s likely, since it’s more true to the winding techniques of the past. Is that sound any better or worse? It’s a lot like drinking wine: The best wine is the wine you like the best.

Like windings in a speaker or an electric motor, the coil wire is covered with a clear coat of insulation—otherwise it would just short out. That coating can be enamel, Polysol, or Formvar. The coatings themselves have no direct effect on a pickup’s sound, but the coating’s thickness can. Fender used Formvar back in the day, although its formulation has changed over the years, and some folks love to debate whether these changes produce sonic differences.

When you see a measure of a pickup’s resistance, it’s a measure of the coil. It’s a factor that may receive a bit too much importance—there’s a lot more to consider. To be accurate, we should technically be discussing impedance, which refers to the ability of an AC signal (your guitar sound) to get through, as opposed to resistance, which is the measurement for DC. The important difference is that the coil’s impedance will vary with the signal’s frequency. Because resistance is much easier to measure using a simple multimeter, that’s what you commonly see in pickup specs.

In pickups, copper wire gauges—running thinner to thicker—are typically 44, 43, or 42. Thinner wire means increased resistance. To use a water pipe analogy, a thinner pipe requires more water pressure. With the same number of windings, thinner wire will result in a smaller coil. The smaller diameter of 44-gauge wire translates to 36 percent less copper per inch than 42 gauge. Tone-wise, thinner wire is generally more mid-centric, and high and low frequencies are not as prominent.

so does magnetic strength.

Increasing the number of windings results in a hotter (i.e., louder) pickup. Therefore guitarists often request overwound pickups, which have a higher resistance measurement. But it’s a misconception that hotter pickups, or pickups with higher resistance, are necessarily more desirable than those with a lower resistance. Curtis Novak is among those pickup makers who play down the importance of resistance as a meaningful measure of performance. “Younger musicians will typically look for the hottest, loudest pickup,” he says. “As players get older, they get more into the nuances. You’d think older guitarists’ hearing would be degraded by many years of playing, but it’s the opposite—they’re more concerned with fidelity and intonation.”

But be prepared, increased fidelity will also result in a pickup that’s less forgiving—you have to play more carefully. String-to-string separation will be clearer, but mistakes will also be more readily revealed. After trying what Novak considers to be his best-sounding pickup model, guitarists often tell him, “I feel like I have to work harder on my technique.”

The bottom line: If you’re thinking about swapping pickups in your guitar, it’s more useful to discuss the sound you’re looking for with a pickup maker, as opposed to requesting a certain resistance or other technical specification.

The Bobbin

On some pickup designs, the coil is created by wrapping the wire around a bobbin—a separate oblong part that is then positioned to place the magnetic poles in the coil’s center. Pickups with adjustable steel screw poles typically use this configuration. Other pickups forgo the bobbin—the wire on Stratocaster and Telecaster pickups is coiled directly onto the magnetic poles. Without a bobbin, the pickup can be smaller. Sound is also influenced because lack of a bobbin brings the coil wire as close as possible to the magnet, strengthening the signal that the coil picks up.

There are other non-bobbin designs. For example, a Danelectro “lipstick” pickup wraps the coil directly around a bar magnet, allowing both to fit within a small, cylindrical metal cover while keeping the number of parts to a bare minimum.

Fig. 6 — Photo by Dan Formosa

Magnet Position and the Magnetic Field

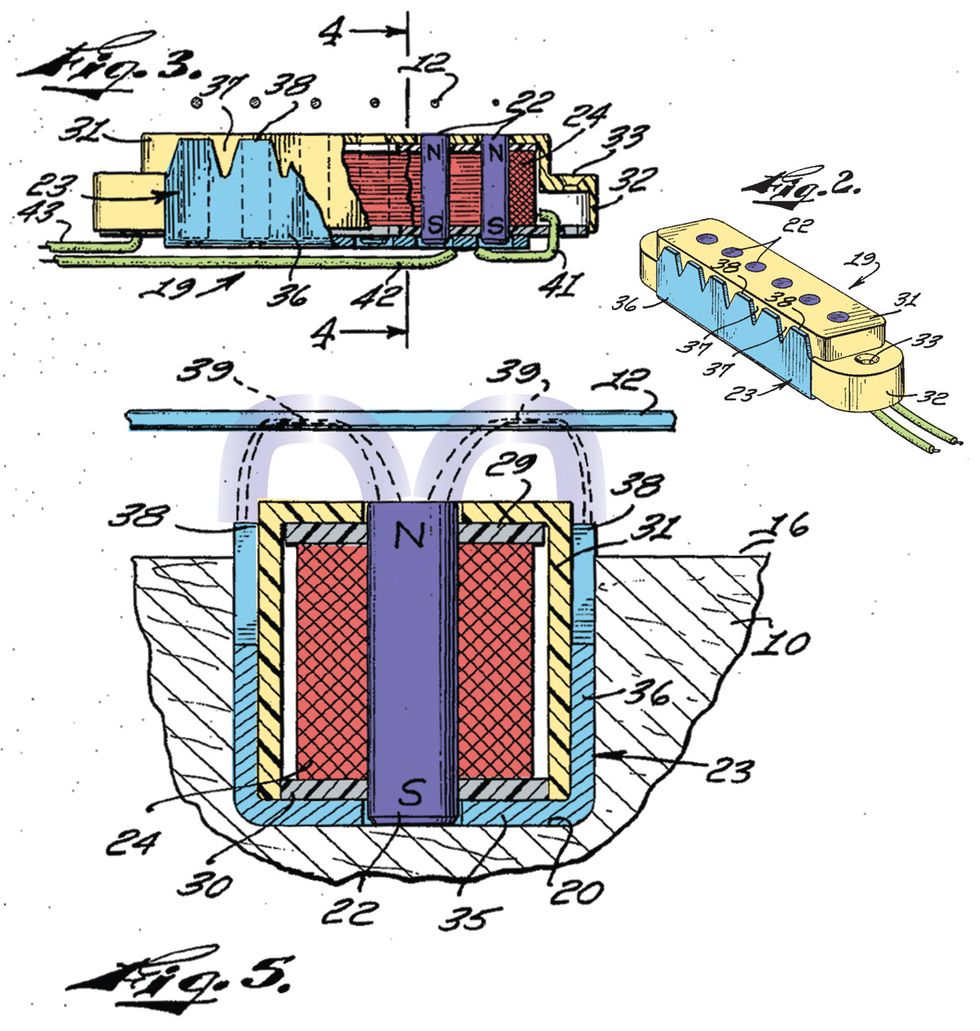

Looking at the pickup poles, one might easily assume where the magnetic field is located—directly above each pole. But it’s not that simple. Other metal in the pickup, and the location of the magnet itself, influences the size, shape, and position of the magnetic field. A pickup’s design that places the magnet within a metal C-channel extends the magnetic field to the edges of the channel. As described in a 1966 patent, one of Leo Fender’s pickup designs goes further by calling for metal “teeth”—formed by notches in the channel—on either side of each of the six poles to further control the area of magnetic force (Fig. 6).

Other pickups using adjustable steel poles locate their bar magnets directly beneath the poles. Simple; it just adds height. As an alternative, Ralph Keller’s 1954 design for Valco pickups places the magnet to the side of the coil and steel poles (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 — Photo by Dan Formosa

A similar configuration is used in the Hilo’Tron pickup from Gretsch. While the original Hilo’Tron included adjustable poles, it unfortunately didn’t provide for an easy way to raise the pickup body. Which is too bad, because bringing the magnet itself closer to the strings makes a world of difference. Proper adjustment on that pickup requires shimming the entire assembly to raise the pickup in a trial-and-error manner—difficult but worth it.

Fig. 8 — Photo by Dan Formosa

Alnico 2, Alnico 5, and Ceramic Magnets

Alnico 2 and 5 are the most common forms of the aluminum/nickel/cobalt alloy magnet. Alnico 5 is stronger than alnico 2—as the numbers increase, so does magnetic strength. There are stronger versions, such as alnico 6 and 7, but they aren’t as useful because stronger magnets can create a harsh tone.

To that point, ceramic magnets, which are less expensive to produce and easier to shape, were commonly used in inexpensive guitars arriving in the U.S. from overseas. There was an additional price advantage: The stronger pull of ceramic magnets meant manufacturers could use less copper wire in the coil. This was truly a cost-cutting measure with little attention paid to sound quality. As a result, ceramic magnets developed a bad reputation, but this may be somewhat unfair.

In fact, ceramic magnets can be effective, if used with care. Seymour Duncan, among others, has developed pickups that employ ceramic magnets wisely, and they appear in several of his models. Curtis Novak has changed his opinion over time. “I used to turn up my nose at ceramic magnets, but I have found some really good uses for them. They can deliver a tone that is not shrill, spiky, and harsh. Using steel poles and a ceramic magnet won’t sound like a Strat, but you can make some really fine pickups by working with the coil and using different grades of ceramic.”

That said, the properties of alnico 5 seem to hit a sweet spot. Too much pull in a magnet requires a weaker coil, too little pull requires a coil with additional windings. Novak’s observation: “When guitar manufacturers embraced alnico 2, it’s because they hadn’t come up with alnico 5 yet!”

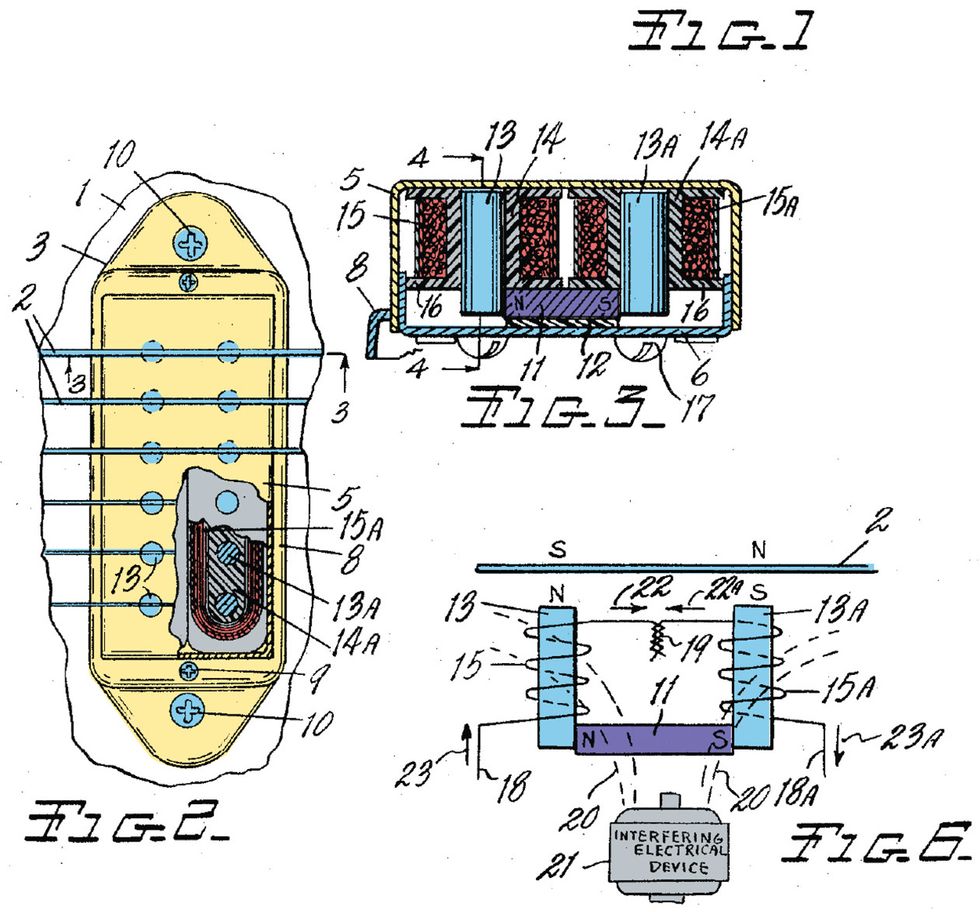

Single-coil and Humbucking Pickups

Hum in a pickup results from stray electric signals reaching the coil. To counteract this annoying sound, humbucking pickups employ equal-but-opposite coil windings that cancel the hum, or at least greatly reduce it to an acceptable level. Their invention is usually associated with Seth Lover’s design for Gibson (Fig. 8) and Ray Butts’ design of the Filter’Tron for Gretsch, which were both developed in the mid 1950s. However, origins of a hum-reducing pickup date to the mid 1930s. The pickup being developed then, patented by Armand Knoblaugh and assigned to the Baldwin Company, was intended to amplify pianos. Going even further back, in 1912 Western Electric created hum-cancelling technology for use in telephone amplification. (See Wallace Marx Jr.’s article, “The Pickup Story, Part III: The Road to the Humbucker” in the December 2009 issue of Premier Guitar.)

The 1950s hum-cancelling designs placed equal-but-opposite coils side-by-side, essentially combining two mirror-image single-coil pickups. For a long time, you could easily identify hum-cancelling pickups by their larger size. But noise-cancelling, single-coil-size pickups were eventually developed to fit into Fender-style pickup cavities.

Fig. 9 — Photo by Dan Formosa

Their coils were either stacked one on top of the other or positioned in line (with one coil wrapping around the poles for the three high strings, the other around poles for the three low strings). DiMarzio and Seymour Duncan have each been offering hum-cancelling single-coil replacements since the mid 1980s. Fig. 9 shows DiMarzio’s 1984 stacked-coil patent.

Check—One, Two

Our final topic concerns pickups that have become microphonic. In addition to the strings interrupting the magnetic field, voltages can be induced simply by vibrating the coil or the magnet. If loose pickup parts begin vibrating with resonant notes or the vibrations in the body of your guitar, the pickup will act like a microphone, ringing unwantedly. In some cases, even yelling loudly into the pickup will transmit your voice through the amp.

The solution is to “pot” the pickup by dipping it in melted wax, securing the parts to prevent them from vibrating. Many pickups have already been potted by the manufacturer. For other pickups that need potting, it’s a quick, simple procedure: Let the pickup soak briefly in a medium-hot wax bath, remove it, let it cool, and then reinstall it. As with so many guitar-related subjects, there’s plenty of debate about how potting can affect a pickup’s tone. Some guitarists prefer the liveliness of pickups that aren’t potted, but if you play really loud, potted pickups reduce the likelihood of screeching feedback.

It’s a WrapThis is an introductory article, so there are plenty of topics we didn’t get to cover. For example, the rubbery refrigerator-type magnets and low winding count used in Teisco’s “gold foil” pickups, or the inner workings of DeArmond’s relatively flat archtop-mounted Rhythm Chief, which we mentioned earlier. But all electromagnetic pickups follow the same science-class principles, and once you understand the basics, it’s easy to dissect any pickup and figure out how it works … more or less. I suspect most pickup designers would agree that pickups, like many other topics, follow a general rule: The more you learn about them, you realize the less you actually know. With that thought in mind, class dismissed.