“I’m not even sure what a ‘Dweezil Zappa’ album would sound like at this point.”

It was December 2012 and Dweezil was excitedly flipping through patches on his Fractal Axe-Fx and describing how he reverse-engineered his way through the tones of his father, Frank Zappa. At the time, Dweezil was neck-deep in Zappa Plays Zappa, a virtousic outfit he put together in 2006 to spread the Gospel of Zappa.

At some point since then, Dweezil figured out what a solo album should sound like—and the result is Via Zammata’. “I didn’t have time to write all-new material, so I dug through what I had to see what could tell the story,” he explains. Part of that story includes “Dragon Master,” the only tune he cowrote with his father, in the late ’80s. From the Arabic melody in the main riff to the decidedly Dio-style vocals and ridiculous lyrics, the song effectively combines the quirkiness of the Zappa universe with the imagery and attitude of classic Iron Maiden.

The new album’s title came from a trip that Dweezil took to Sicily. He was there to learn more about his father’s family, and discovered the street his ancestors lived on. “The name of the street was Via Zammata. The building [they lived in] was just tiny,” says Dweezil. According to what he learned from the locals, the word “zammata” has a rather complicated meaning. “We don’t really have a word like it in English, but it’s used to describe the sound of children’s footsteps playing in a rain puddle.”

Expanding the orchestration of rock music is a thread that weaves in and out of the Zappa cannon. With this latest album, Dweezil decided to put the songs and arrangements up front rather than creating a wall-to-wall shred fest. “I wanted to get to the simplest version of each song,” he relates. “Even saying that it’s simplistic—that’s not really the case for every song, because there’s something a little twisted in all of these.”

Those twisted ideas might be demonstrated best in “Malkovich,” a dark and spacey jam centered on a spoken word performance by John Malkovich, the actor. The fuzzy riff and Devo-like chorus came together rather quickly, as the band wrote, recorded, and mixed the whole song in a single day. “It’s funny. When I go back and try to learn the main riff, it’s hard to hear the ‘B’ part of the riff because of the mix. I have to strip stuff away so I can actually hear what I played,” Dweezil says, laughing.

Considering the ever-changing landscape of the music business, Dweezil took a more inclusive approach to recording and releasing this album and used PledgeMusic, a crowdfunding website, to bring fans into its creation. It was not the action of a desperate artist, but, rather, a way to give them a peek behind the curtain. “It was about telling people I’m making a record and asking them if they want to be involved from the ground up,” says Dweezil.

The excitement in Dweezil’s voice is palpable. On his latest tour with Zappa Plays Zappa, the band joyfully tackled his father’s One Size Fits All album in its entirety to celebrate the 40th anniversary of its release. PG caught up with Dweezil between his daily master class and soundcheck to talk about the Beach Boys, improvisation, and a quasi-secret all-star guitar project that has been decades in the making.

You hold master classes before each show on tour. Did the desire to do these come from a formative experience you had in your youth?

I know how important it was for me seeing Eddie Van Halen, my dad, or Steve Vai up close. I know what the value of that is in terms of how it can completely change your playing overnight. When people started asking me about how to play stuff, we started the Dweezilla Music Boot Camp. But then I got too busy to keep doing the camp—but I do want to bring that back—so I started doing 90-minute master classes on the road.

What do you get out of doing these classes?

I don’t have a lot of time on the road to practice, so when I’m trying to explain something it further engrains the concept for me. My approach is to take something that you already know and expand your vocabulary by creating a strategy to look at it three or four different ways. I try to make it feel like it’s not this daunting thing that you have to memorize. I explain some pretty complex subjects, but I try to make them as simple as possible.

Was there a particular “light bulb” moment that changed how you view improvising?

When I was about 12 I discovered how to organize the fretboard into three sets of two strings and that they were mirror images in all these patterns. Then, I wasn’t thinking about playing in these vertical boxes. It just helped to connect ideas. I still take lessons with people that do stuff that I don’t know about.

How has your view of improvisation evolved while playing your dad’s music?

When I started working on my dad’s stuff I had to really think about true improvisation and not relying on a bunch of standardized, pre-composed licks. I grew up in an era when guitar solos were composed. Eddie Van Halen composed solos. Randy Rhoads composed solos. You found the perfect solo for the song and there was something cool about that. My dad didn’t do that at all. He wanted to be right in the moment and react to what was happening. You have to have an entirely different vocabulary. I had to make the mental change as well as the physical, technical changes. I’ve been doing Zappa Plays Zappa for 10 years and I’m just now getting to the point where I feel like I’ve developed enough vocabulary to really go off script. Every time I play “Inca Roads,” I try to play an entirely different solo, with stuff I haven’t done before.

How do you balance familiar elements of a solo with newly improvised passages?

What I try to do in Zappa Plays Zappa is play in context to the music. I want to play in a way that Frank might have played, use some of the phrases he actually played, but add my own ideas as the line to get there. And if you have a sound that’s evocative of the era or a specific thing from the record, that’s helpful too. I don’t like to hear people play Frank’s music and go off in a direction that sounds nothing like what Frank would have done on a solo. Some people think that’s what your supposed to do. For me, even if I learn a Van Halen or Jimi Hendrix song, I want to learn how to play the exact notes that they played and the same phrasing, because to me that’s playing the song.

You mentioned that some of the tunes on Via Zammata’ came from older demos.

I took some songs and rearranged things. Then I ended up writing a couple of things. “Funky 15” was written for this album. “Truth” was originally going to have lyrics, but I ended up going more towards a Jeff Beck-style instrumental. Then there was “Dragon Master”—I tried to add some of my interest in Arabic music into that song. All the things I did with textures and stuff was a result of my experience in playing with Zappa Plays Zappa. The songs came out different because of the experience of breaking down arrangements in Frank’s songs. The songwriting is different because, for lack of a better description, it’s more like a pop singer-songwriter record than a big guitar album. To a large degree, most of the material on here is less complex than anything from my previous records.

“Dragon Master” on Via Zammata’ is a full-on Maiden-meets-Sabbath metal song that Dweezil cowrote with his father, Frank. Photo courtesy of Dweezil Zappa

There are some highly pop-influenced vocal harmonies on the album. Did that influence come from pop music you heard when you were growing up?

The only music I heard growing up was my dad’s. I started listening to the radio when I was about 12. Then, I started hearing The Beatles and other things. I only ever heard what Frank was working on at home, or if he was listening to someone else’s record. But over the years I developed an interest in certain things, like The Beatles. I was never a big Beach Boys fan, but I liked the harmonies. As I got older I could appreciate that even more. I was driving home and heard “I Get Around” on the radio and I was like, “You know what? That’s a fucking badass song.” Nobody writes songs that are like that in the sense where it’s all about the vocal arrangement driving the whole chord progression. When a song like “I Get Around” came out there was nothing that sounded like that. And there still really isn’t, to a large degree. There’s some type of Baroque element to some of the Beach Boy harmonies. There’s classical counterpoint-type stuff, even though it’s crafted into a surf-y pop song. “Rat Race” [on Via Zammata’] sounds a little like The Beach Boys meet the Bulgarian Women’s Choir.

How did you craft those harmonies?

They were written on guitar. [The session vocalists] would have the lyrics and hear the melody of what the harmony is supposed to be; they could sing along to the guitar line until they got it in their heads. It was way easier to do that.

Did you take the same approach with the string arrangements on “Truth?”

I wrote the parts and then Kurt Morgan, the bass player, went into Finale and further orchestrated it enough to be able to give it to real people to play. I played all the parts on guitar first. I don’t read music; I just write it and record it. If I need to show it to someone I have to record something and say, “Here’s how it goes.” Then they have to transcribe it.

Dweezil Zappa's Gear

Guitars

Gibson Frank Zappa “Roxy” SG with Sustainiac and piezo pickups

Gibson fretless SG

Gibson ES-336

Fender Hendrix/Zappa Strat

Fender Eric Johnson Stratocaster

Fender Johnny Marr Jaguar

’60s Fender Telecaster

Godin MultiOud

Godin Glissentar

Coral Electric Sitar

Amps

Fractal Axe-Fx II

1966 “Black Flag” Marshall JTM50

Fender Super Reverb

Port City Pearl

Effects

JHS Pollinator

JHS SuperBolt

JHS Twin Twelve

Strymon TimeLine

Strymon BigSky

Strymon Mobius

Greer Lightspeed

Greer TarPit Fuzz

Maxon Fuzz Elements Air

Maxon Fuzz Elements Water

Source Audio Soundblox 2 Orbital Modulator

TC Electronic Vortex Flanger

TC Electronic Shaker Vibrato

Little Labs PCP Instrument Distro Rev. 3.1 signal splitter

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball (.009-.048)

Red Bear Trading Company custom picks

How did you organize the music from the older demos to present them to the band?

Since some of the songs already had a demo, the band could hear how I did it 20 years ago, and then I’d show them how I’d do it today. It was pretty simple. We actually recorded all the basic tracks in about six days. It took a long time to decide how to add all the overdubs. Part of what I wanted to do was—as far as guitars went—take a back seat, to a degree. This is my first record that has full instrumentation, like keyboards and other things. So I wanted to make sure the vocals were a key part and the bass lines were really featured.

The vocals and bass lines were your guideposts when arranging and writing the tunes?

In terms of what should be able to drive the song forward, the guitar was more texture on top. The foundation was really the bass line and the vocals for most of the songs. As far as the guitar sounds went, I wanted things to be mono and really specific in the stereo field. A lot of the songs might have little counterpoint parts. There’s always something fixed in just the left speaker. It might have a little answer on the right side. I wanted to simplify my approach in a lot of ways. That’s how it started and then some of the songs got complicated over time.

What songs took the biggest leap from demo to album?

Some of the demos had more on them than the finished versions on the record, so it was really about stripping away stuff. The song “Nothing,” for example, has one rhythm guitar part through the whole thing with a couple little lead lines and a solo at the end. There’s one clean rhythm part that sits on the left side and then you have ambience on the right side that gives it some spatial representation. I wanted it to sound like you were making an old analog record and you had to really not use up too many tracks and be very specific with your ideas. But then some of the songs had lots of tracks. “Hummin’” has a lot of different textures. “What If” has a fair amount of overdubs. “Dragon Master” has two mono rhythm guitars. In the chorus there’s a third guitar that comes in. “Rat Race” has one guitar. “On Fire” has a lot of textures, but it mainly has a pretty clean guitar and a slightly distorted guitar to give it an edge. “Jaws of Life” has one electric rhythm, some acoustics, and a fuzz guitar that comes in.

“Malkovich” is an incredibly interesting song, with the spoken word performance. Where did that come from?

I love his movies. He’s a great actor. He did this cool photo exhibit and he wanted to have a music element to it. The idea that he and his cohorts came up with was that he would do a spoken word performance and then give it to 12 or 13 people and say, “Here, do what you want.” Ric Ocasek did a tune, Yoko Ono, Andy Summers, and some others. [The results are on Malkovich’s album, Like a Puppet Show.-Ed] I haven’t heard anybody else’s tracks, but the thing that’s funny is that we all had the same [vocal performance] to work from. The other weird thing, which is very John Malkovich, is that all of the songs have to have the word “cryo” or “genia,” or have an X or Y in the title. My song—it’s coming on my record and his at the same time—is called “CryoZolon X.”

We have to talk about “Dragon Master.” You mentioned it was the only song you wrote with your dad.

He gave me the lyrics in 1988. Over the years, different versions of the song came together but we never released them.

Did he get a chance to hear a version of it?

Yeah, he heard a version of it back when the whole thing was more of a joke. For example, his lyrics are clearly a joke, so the early version made fun of metal and had some speed metal things in it and was heavier. On this record I wanted to actually play the idea more seriously and make it a full-on traditional metal song. Like Iron Maiden meets Black Sabbath, but for real! Anyone who’s a metal fan can hear the lyrics and clearly know that they are preposterous and a joke. But people that are into metal, the imagery that is created by the lyrics—it’s not a joke to them. They are like, “This is fucking dead serious. It’s time for business.” One of the fun things about doing the vocals is that the guy who sings it, Shawn Albro, is actually a cousin of Ronnie James Dio. So we [asked him] to put some Dio-isms in it, and Shawn was like, “What do you mean?” You know how Ronnie sometimes adds an extra syllable to a word that doesn’t need it? There’s a line that says, “Hate the day. Hate the light.” So I had him add an extra syllable to “light-a.” I did my best Dio impression and he was like, “Oh, okay. So make it cool?” That’s what I love about that song, because it stands on its own. If this were 1982 this would be the biggest fucking metal song in the world.

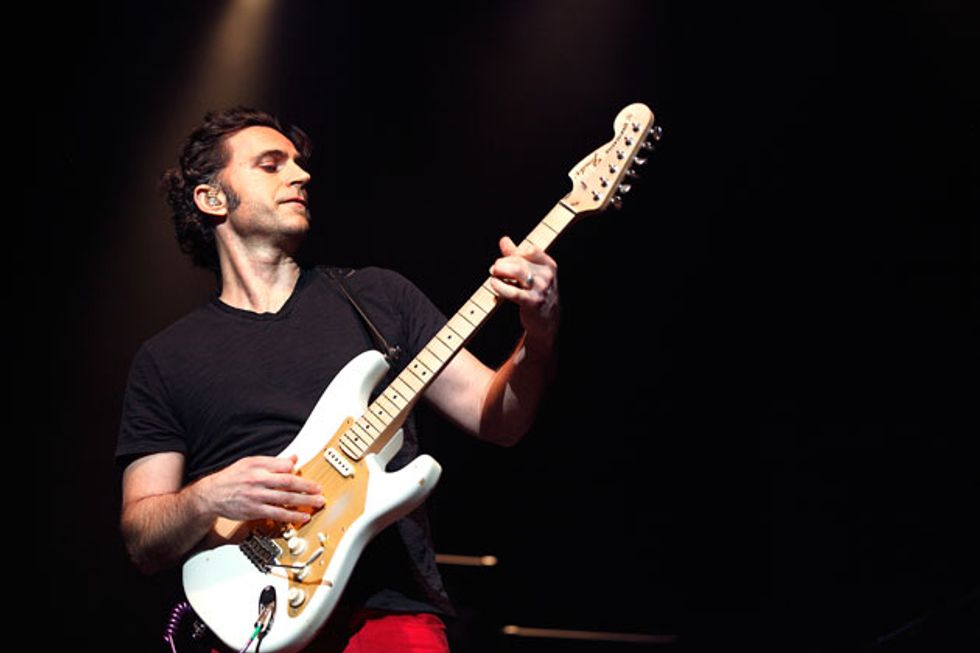

For the last decade, Dweezil has fronted Zappa Plays Zappa, an incredibly virtuosic group that pays tribute to his father’s immense catalog of music. Photo by Ken Settle

Your live rig is really based around combing the digital and analog worlds. How did you balance that in the studio?

I hadn’t been playing through amps in about six years. I wanted to go back to an old-school approach and see if I’d been missing anything by using the Axe-Fx. I didn’t really use it at all on the record except for “Malkovich.” That rhythm track was played through a preset. Everything else was mostly a “Black Flag” Marshall—the Angus-style one. Then there was also this Port City Pearl. I liked all the sounds I got on the record, but I could make all the sounds with the Fractal without any problem.

Amp modeling has come such a long way. At this point, what do you feel are the differences?

It used to come down to the feel. If you did a blind test and the feel and response changed, you could tell. But now that’s right on the money. As far as audio goes, it’s all right there. I prefer the Fractals for what I have to do in Zappa Plays Zappa, because I have to refer to 30 years of recording technology in order to come up with different sounds. Sometimes my dad would split a signal four different ways with a clean direct sound mixed in with three different amps and other effects. I had a big analog rig for the first two years, but it just started to break down, it was really expensive to take everywhere, and it was loud onstage. Everything improved when I started using the Fractals live. Now you can get a real stereo spread in the PA and you can actually be in the PA.

You got such a wicked fuzz tone on the solo to “Truth.” What did you use for that?

That was the Marshall and, if I’m not mistaken, the Port City amp with a JHS Pollinator and a JHS SuperBolt. The Pollinator has a great front end. I also used it on the solo to “Jaws of Life.” It makes this broken, under-biased sound. Neither pedal had a very high-gain sound, but the fretless guitar has the Sustainiac, so it allowed me to keep those notes going. It was really about getting the texture of the attack of the front edge of the pick.

How did you first approach the fretless guitar?

It was definitely weird. Gibson made me a fretless SG, but it has a Sustainiac pickup and piezo in the bridge along with Antares Auto-Tune, which gives you a lot of different tunings. You can still play all the fretless gliss stuff without it sounding chromatic, and it will actually let you play chords in tune. The guitar is very complicated to make. But I plan to use it more for other things. I need to spend more time with it because I got it just in time to do a couple overdubs on the record.

You’ve been working on this somewhat secret all-star guitar project for decades. Has there been any progress on that?

It started on analog tape as something that was just going to have a few guests on it—maybe only 10 or 12 minutes long. Then it kept growing into a 75-minute piece of music and now there are over 40 people on it and there’s still more people to put on it. I got busy with a lot of other stuff and didn’t work on the project for a while. The last time I worked on it was about a year ago. I took all of the stuff that was on tape and put it on the computer. Over time I had been putting in pieces of my dad’s music. This was way before I was doing Zappa Plays Zappa. It [started] more than 20 years ago. I have new spaces to write new stuff. I think I’m going to turn it into a surround-sound mix. It’s basically an audio movie. The music—the audio soundscape—changes moment by moment.

A film score without the film?

Yeah. It’s like if you were to see a movie that had a bunch of extras in the background, but they were all famous actors. Somebody would come into focus here or there. That’s what happens. Like, “Oh, that’s Yngwie Malmsteen. That’s Angus Young, or Eric Johnson, or Eddie Van Halen, or Brian May.” The music changes every time somebody new steps forward. I haven’t recorded anybody in the last decade, but I do want to get more of the classics on there, like Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page—it would be good to get Clapton. Of the newer players, I’d like to get Tim Miller. He’s one of my favorites. Richard Hallebeek—he’s really good. Guthrie Govan would be great. There was a section that Frank was supposed to play on, but he got too ill so I played on it. I remember I took all the strings off the guitar and just left the D string. I purposely played an entire solo on just one string.

What I have to do is block out some time to finish. But it might take more than three months. It’s a pretty crazy project. It would be a good Pledge campaign. I have another idea for it, but I think it’s better if I keep it to myself right now.

YouTube It

During the fall 2015 tour, Zappa Plays Zappa performed Frank Zappa’s One Size Fits All in its entirety. Each night the show opened with the band playing the theme to Star Wars before heading into the album’s well-known first track, “Inca Roads.” Dweezil begins the song’s signature guitar solo odyssey—a longtime highlight of his father’s concerts—at 4:36.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)