Chops: Intermediate

Theory: Intermediate

Lesson Overview:

• Dive into Delta blues, Texas blues, ragtime, Piedmont, and boogie-woogie styles.

• Learn monotone bass, alternating bass, and boogie-woogie techniques.

• Explore syncopated rhythms.

Click here to download the accompanying mp3 audio examples and a printable PDF of the notation.

Okay folks, time to put down that pick because today we’re focusing on acoustic fingerstyle blues. Obviously there’s a large body of music that falls into this category, which can be further broken down into such sub-styles as Delta blues, Texas blues, ragtime, Piedmont, and boogie-woogie. This list is by no means exhaustive, but these are the styles we’ll cover in this lesson. Instead of trying to learn each sub-style from a theoretical or historical perspective, I’ve decided to approach learning it from a guitar technique perspective, specifically focusing on the picking-hand thumb.

In solo fingerstyle guitar, the thumb typically takes the role of the bass player. The bass player, our thumb, crafts lines in a few distinct ways. Today we’ll look at three types of bass lines that help define the sound of the aforementioned sub-styles of fingerstyle blues: monotone bass, alternating bass, and boogie-woogie bass.

Delta Blues and Texas Blues

There’s no better instruction than listening to recordings or viewing video, if available, of the blues greats we are trying to learn from. Take a moment to watch Texas bluesman Lightnin’ Hopkins’ perform “Baby Please Don’t Go,” Delta blues master Son House perform “Preachin’ the Blues,” and finally Chicago blues great Big Bill Broonzy play “Hey Hey.” Pay special attention to their right-hand technique—specifically their thumbs—and you’ll see each of them employing a monotone bass line.

Lightnin’ Hopkins – “Baby Please Don’t Go”

Son House – “Preachin’ the Blues”

Big Bill Broonzy – “Hey Hey”

The monotone bass line is a static line that’s typically created by playing a chord tone from a given chord in the song’s progression. Often the chosen chord tone is the root. In Fig. 1, the chord we’re dealing with is E and the root is—you guessed it—an E. In this example, the bass line consists of quarter-notes. Playing this with a slight palm mute and a little bit of attitude goes a long way towards achieving the rhythmic drive found in this style of blues.

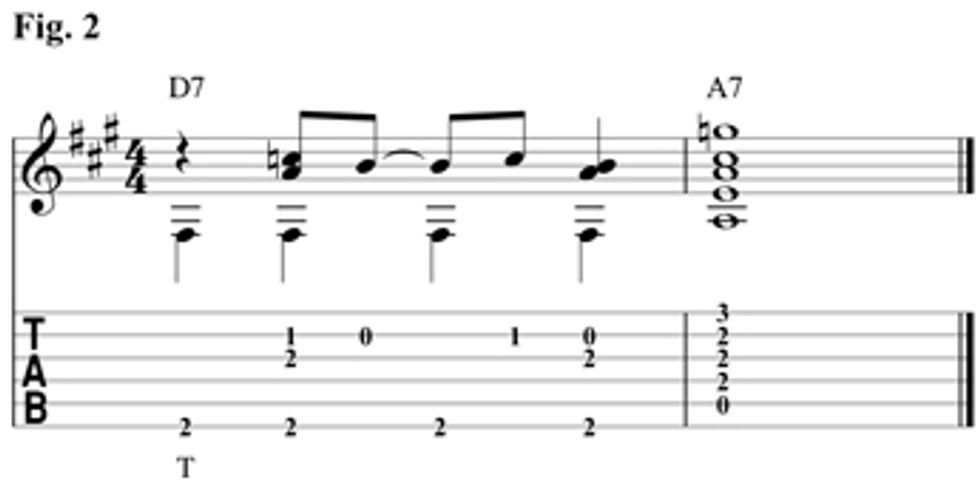

The chord root is not your only choice for bass notes. In Fig. 2, the 3rd (F#) of D7 is used as the bass note and is played with the thumb. This is a common monotone bass note choice for this chord, especially when D7 functions as the IV chord in an A blues progression.

Fig. 3 is an E blues I’ve written in the style of Lightnin’ Hopkins. The thumb should drive this tune, but be careful that it doesn’t overpower the fingerpicking. Watch the demonstration video and pay special attention to the “thump” of the bass line, as well as the inflections used on the melody. In the written example I’ve avoided notating the bends, so watch the video to see and hear where the bends occur. For added authenticity, listen to the masters and imitate the way they bend and phrase notes in this style. After watching the video take a look at the TAB. Before trying to play it, first locate all the chord shapes on the fretboard, since much of the melodic material is played out of these shapes. After doing this you’ll find that from a left-hand perspective, this tune is fairly accessible.

Piedmont and Ragtime Blues

In the next style we’ll examine, the thumb typically plays an alternating bass line, usually composed of quarter-notes, with the remaining picking-hand fingers providing syncopated melodic material. (A syncopated rhythmic figure emphasizes the weak part of the beat—the “and” of the beat.) These sounds are heard in the ragtime and Piedmont styles of players like Blind Blake, Mississippi John Hurt, and Reverend Gary Davis. The bass lines played in this style differ from the Delta style in that they alternate between chord tones instead of having a monotone bass note driving a single chord tone. Take a moment to watch the following videos of a few greats in this style.

Mississippi John Hurt – “You Got to Walk That Lonesome Valley”

Elizabeth Cotton – “Freight Train”

Now it’s your turn. If you are new to this style try starting with Fig. 4, which is an example of an alternating thumb pattern played over a C chord. In fact, hold the entire C chord down while playing the line and use only your thumb to pick the notes.

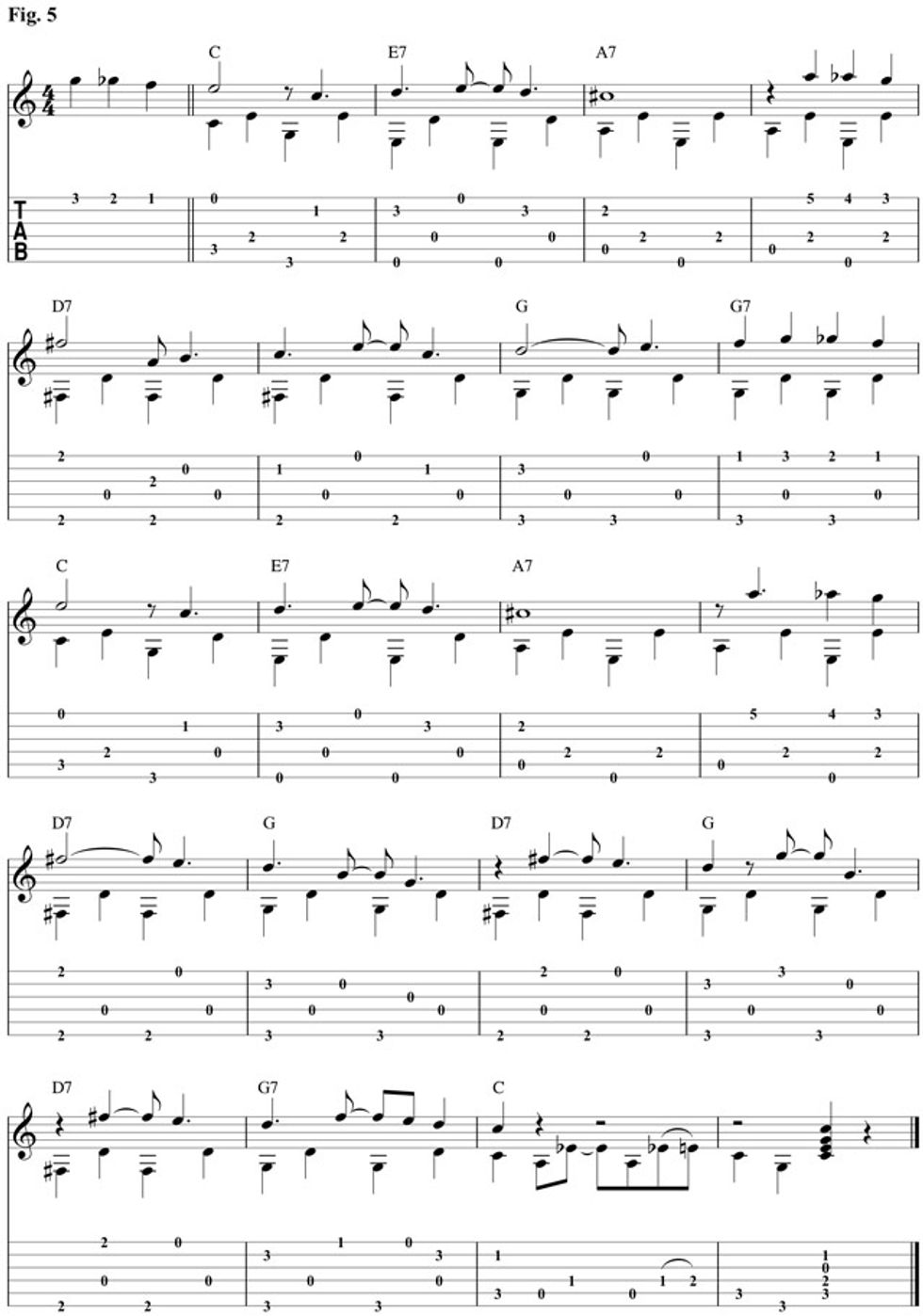

Fig. 5 is a piece I’ve written in this style and is based off of the chord changes found in Blind Blake’s “West Coast Blues.” When learning this piece, a great place to start is with the chords. Follow the chord changes listed above the notation. While holding the chord shape, play the bass notes listed. In the standard notation the bass notes are the notes with stems pointing down. The bass line must be solid, so work with a metronome to keep a steady beat. Once you are comfortable changing chords and keeping the bass line going, start adding the melody. There’s a fair amount of syncopation in this example, yet with the exception of the A7 chord, all of the chords are basic open-position forms. Play the A7 chord by barring at the 2nd fret with your first finger, so you can play the melody with your remaining fingers. Note that D7 is the same voicing we used in Fig. 2.

Boogie-Woogie Bass

Before we dig into this section, check out the following videos.

T-Bone Walker – “T-Bone Shuffle”

John Lee Hooker – “Shake It Baby”

The first is T-Bone Walker performing “T-Bone Shuffle,” and you’ll want to listen closely to the piano. The second video is John Lee Hooker playing “Shake It Baby.” Are you ready to boogie?

Let’s close this lesson by taking a look at a few bass lines commonly found in the boogie-woogie blues style of guitarists and pianists. These bass lines are primarily constructed from chord tones. Fig. 6 and Fig. 7 present two possible bass lines you can play over A or A7. Fig. 6 is constructed from the root, 3rd, 5th, and 6th (A, C, E, and F# respectively). The bass line in Fig. 7 sounds a bit bluesier due to the inclusion of the chord’s b7 (G).

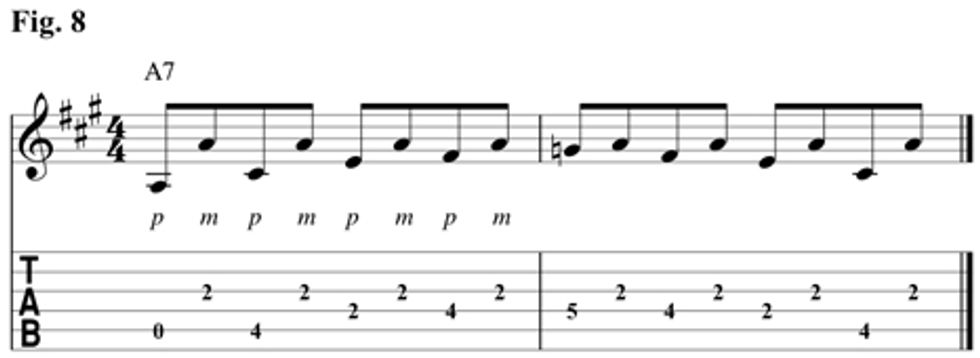

Practice playing these two examples using only your thumb—you’re going to need the other fingers very soon. Once you’re comfortable playing Fig. 6 and Fig. 7, it’s time to create variations. First, let’s change the rhythm from quarter-notes to eighth-notes as in Fig. 8. Play it with a swing feel. As you listen to the recording, notice how the eighth-notes are not equal. By placing a chord tone above the bass line (in this case the root), you’re starting to imitate the sound of a pianist playing a boogie line. Continue to play the bass line with your thumb (indicated by the p). For the top note, you can choose to use either the index (i) or middle (m) finger.

We can thicken the sound of our boogie line by adding another chord tone above the bass line. In Fig. 9, barre the A and C# (the 3rd of the chord) with your first finger. The other fingers are now free to play the bass line. With the thumb playing the bass notes, use your index and middle fingers to play the accompanying chord tones.

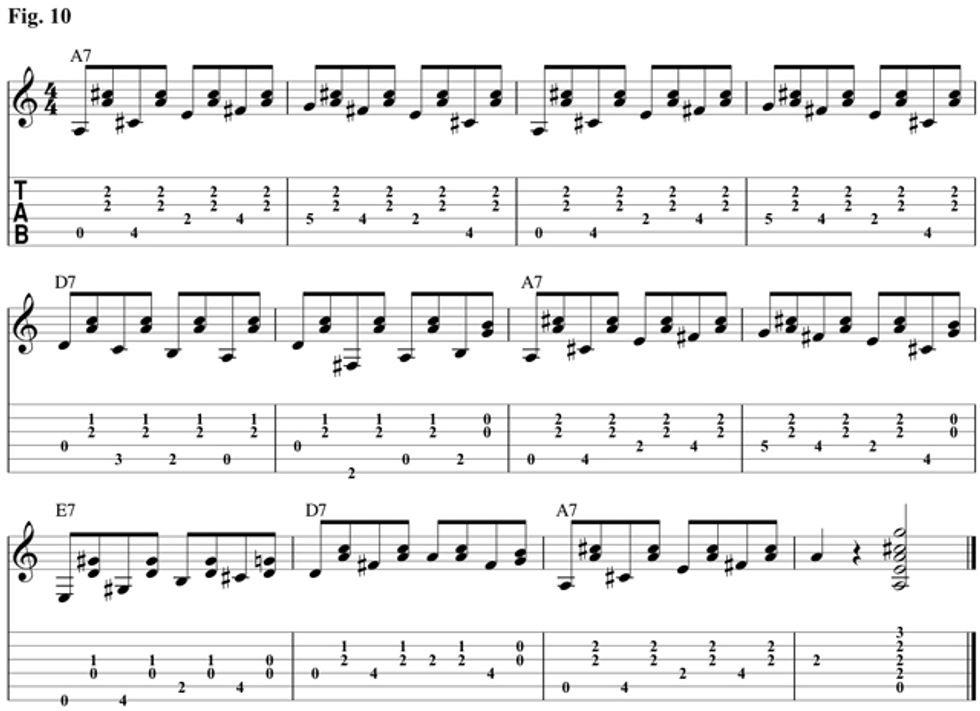

Fig. 10 puts everything we’ve discussed into practice with a 12-bar blues in the key of A. In measure 5, I’ve adapted the bass line so that it does not “run into” the notes in D7. However, the bass line is still composed of chord tones. As you apply boogie bass lines to your own songs and arrangements you may run into a similar issue. If so, strive to create a line that not only grooves, but is also melodic. Notice in measure 10, beat 3, the bass line “runs into” the chord tones above. I decided to keep it this way because I wanted to retain the melody created in the bass line. There are no exact formulas that you must adhere to. Instead, trust your ear. Strive to create boogie lines that meet the following criteria: They are melodic and they groove!

You’ll notice that on the last eighth-note of measures 6, 8, 9, and 10, you play open strings instead of the expected chord tones. By playing these open strings, you buy extra time for your fretting hand = to set up the next chord, and this allows for a clean transition from one chord to the next. If you play this example with a steady beat, even at a medium tempo the ear hears the “appropriate” notes because the sound of the chord has already been established earlier in the measure.

Where to Go from Here

Playing blues in a solo fingerstyle context is a lot of fun and very rewarding. I hope this brief survey of a few sub-styles of the blues has inspired you to dig deeper into the music. I can’t stress it enough: Listen to and study the masters. Learn their songs and licks, but more importantly, absorb the feel of the music. If you can find a knowledgeable teacher to study with—whether it’s one-on-one or in a group setting—take advantage of it. This will have a tremendous effect on your rate of growth. Today there are plenty of guitar camps and workshops available that provide an opportunity to study with some of the living legends of this music. Have fun and good luck!

Recommended Listening

Here are a few recommended recordings. Many of these are compilations or “Best of” albums, so they’ll be especially helpful to those of you who may be new to this music or the artists we’ve discussed in this lesson. I have also created a Spotify playlist with selections from many of the albums listed below.

The Tradition Masters

Spend some time with this recording and you’re bound to pick up a few classic blues licks. Check out Hopkins’ monotone bass accompaniment on “Long Time.”

Warm, Witty, and Wise

Here’s a nice collection of songs showcasing Broonzy's solid fingerstyle technique. Listen to “Long Tall Mama” and “Worrying You Off My Mind Part 1” as they creatively employ the monotone bass thumb technique we’ve discussed.

1928 Sessions and Best of

These classic albums showcase great examples of alternate thumb technique along with Hurt's overall beautiful playing style. Check out “Stack O Lee” and “Got the Blues, Can’t Be Satisfied” from the 1928 Sessions, and “My Creole Belle” and “Make Me a Pallet on Your Floor” from the Best of recording.

The Best of

Great feel and drive is found in Blake’s music. You’d swear there’s more than one guitarist here. A few of my favorite tracks are “West Coast Blues” and “Blind Arthur’s Breakdown.”

Blues & Ragtime

As the title suggests, there are wonderful blues and ragtime tunes found here. Check out “Buck Rag” for the cool counterpoint. Included in the liner notes are transcriptions (written in standard notation and TAB) of “Walkin’ Dog Blues,” “Buck Rag,” “Cocaine Blues,” “Hesitation Blues,” and “Baby, Let Me Lay It on You.”

The Complete Recordings

These are classics that all aspiring blues guitarists should spend time with. Johnson’s performance of “Kind Hearted Woman Blues” is a great example of the monotone bass accompaniment.

Original Delta Blues

This is a great compilation showcasing the raw and powerful playing of one of the great bluesmen. Take a listen to “Pearline” to hear it for yourself.

20th Century Masters: The Best of John Lee Hooker (Millennium Collection)

If you need to add some boogie-woogie into your day, listen to “Shake It Baby” and “Lonely Boy Boogie.” These tracks are great examples of raw boogie-woogie.