In an age when pedal dimensions are decreasing in inverse proportion to functionality and flexibility, the Valco KGB Fuzz looks monumentally large (and a lot like a piece of lab equipment from a CIA cold-war gizmo room).

Distributed by the folks at Eastwood Guitars, it's inspired by the Lovetone Big Cheese fuzz, a similarly large 4-knob fuzz famously used by Jimmy Page, the Edge, Gary Moore, Kevin Shields, Johnny Marr, and others in the late '90s and early aughts. (Bassists Bootsy Collins, Larry Graham, and Radiohead's Colin Greenwood are also fans—the latter reportedly uses it live for "The National Anthem.") KGB Designer Carl Cook says he's treasured his own Big Cheese since receiving it from his former record label in 1997. But he also wished it had more output and oomph, as well as the extra features and capabilities we see here on the Valco.

Recorded with an Audient iD44 into GarageBand with no EQ-ing, compression, or effects.

- Squier Jaguar Curtis Novak neck pickup into SoundBrut DrVa MkII and Ground Control Tsukuyomi boost pedals and an Anasounds Element reverb, then into both a 1976 Fender Vibrolux Reverb miked with a Royer R-121 and a Fender Rumble 200 1x15 miked with an Audix D6. KGB first bypassed, then cycling through voices (off, 1, 2, 3) with blend first at 50 percent, then 100 percent. Output at 10:30, tone and fuzz at minimum.

- Jaguar bridge pickup into same setup as clip 1. KGB first bypassed, then cycling through voices with blend at 100 percent, output at 9 o’clock, tone at noon, and fuzz at 1 o’clock.

- Squier Tele with Curtis Novak pickups (neck and bridge) into a Sound City SC30 miked with a Royer R-121.KGB first bypassed, then voice 1 with blend at 100 percent, output at 10 o’clock, tone and fuzz at noon, and impedance at 10k.

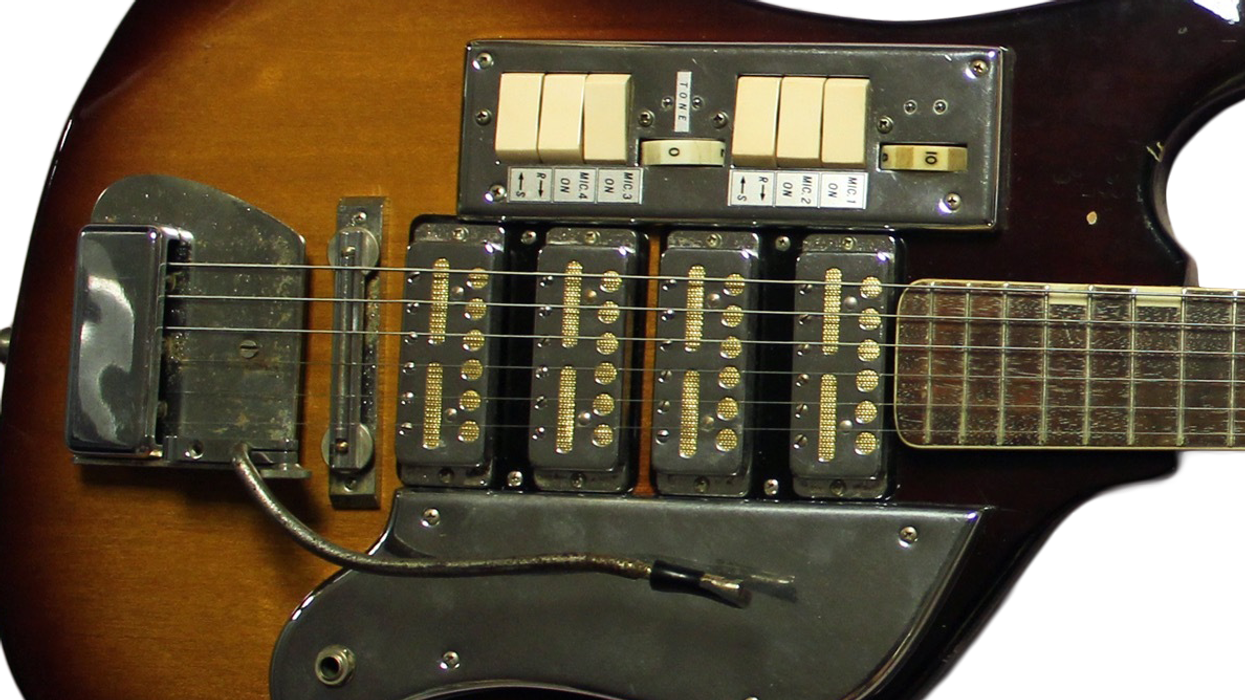

Quite the Charcuterie Board

The heft of the Canadian-made KGB's steel-and-aluminum enclosure, and the snugness with which the knobs, jacks, slider, toggle, and footswitch are fastened inspire confidence. When you pull up on the footswitch to reveal the two neatly wired and soldered circuit boards (one small, one moderately large), you might wonder if the extra space is intended to conceal a secret agent's pistol. Alas, KGB is just a cheeky acronym indicating adaptability with keyboards and bass as well as 6-strings. Circuit board components aren't visible without taking the unit apart. But Cook tells us the main clipping elements are a silicon diode and an NPN transistor wired as a diode.

The KGB control panel sports the output level, tone, and fuzz knobs you'd expect. But the rest of the interface is quite unique in form and function. Like the Big Cheese, it has a 4-position voice knob. In the "off" position, the pedal's tone knob is bypassed. Voice 1 engages the tone control with a midrange scoop at 1 kHz, availing Big Muff-like sounds and response. Voice 2 has what Valco calls a "more neutral EQ" with more mid emphasis. Voice 3 incorporates the same EQ as voice 2 but adds another gain stage and a bias shift in the preamp to yield a more Velcro-y, gated response at higher fuzz settings.

Along the left side of the unit is the wet/dry slider, a powerful addition that's unique for how handily it lets you adapt KGB to other instruments without sacrificing low end or fundamental clarity. It's also easy to manipulate with your foot. Among other things, it's fantastic for making things sound like you've got a second guitarist doubling your lines. (To take this sound to epic extremes you can set the blend to full wet and route the dry output and effected outputs to separate amps or the P.A.)

Impedance isn’t typically something we get super excited about … but here [it] actually becomes pretty frickin’ exciting.

There's no need to do any math to figure out which impedance settings work best. All that matters is whether you like how each setting sounds. As a general rule, lower impedances yield mellower, less pointed tones, and as you click toward the 1M mark the control increases and morphs the quantity and quality of the saturation. But different impedances alter much more than tone. With very little linearity, the Ω knob can affect attack, bloom, intensity, and decay in ways that are beautifully, chaotically unpredictable.

The Verdict

There's so much going on with the Valco KGB that it's difficult to describe it thoroughly in this limited space. But whether you're a jaded veteran or an abject beginner in the fuzz game, KGB could feasibly be any kind of fuzz you've ever wanted. Love thick Muff sounds? They're here. More of a Tone Bender player? Okey-doke. The twisted sounds of a Fuzz Factory? Check. But KGB is also a super characterful, straight-ahead distortion box—some of my favorite sounds emerged with fuzz at minimum.

The only bummer I encountered with the KGB was when I inserted it in my usual fuzz-box location on my own pedalboard, which is after my wah. KGB prefers to be at the beginning of your chain, and buffered bypasses within the signal path may render the Ω knob virtually useless. Though the Valco is big, with so many handy, adaptive features, you'll probably want to make space on your board to accommodate it. Or maybe you'll simply thrill to the unadulterated glory of playing it straight into an amp with your guitar and nothing else.

But even if you can't live without your fuzz being somewhere in the middle of your signal path, KGB serves up a wealth of exciting fuzz action. No matter what I played it with—from a Telecaster to a Jaguar or a Gretsch with Filter'Tron-style humbuckers, low-wattage, small-speaker amps, larger Fender combos, or British-style amps—the Valco became a dirt-box playground. It's going to be tough letting this one go back to the company!