It’s one of the earliest effects pedals and one of the most enduring, but for many players the fuzz box is still ghettoized as either the domain of “old-school” genres like psych, garage, or Hendrix-esque classic rock, or the torture device of noisemakers and experimentalists.

The truth is, this ridiculously expressive effect can do much more than just freak-out leads: Fuzz has been used by great artists in virtually every genre—and from Newark to Nigeria—to produce groundbreaking music. A good fuzz box can add character to just about any conceivable style, taking you from subtle grainy textures to woolly thickness, sputtering fizz, or myriad flavors of utter mayhem, all with superb touch sensitivity. And yeah, it’s still great for acid-rock freakiness. But as everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Jimmy Page, J Mascis, Jack White, Billy Corgan, and Dan Auerbach has proved, there’s truly a massive variety of tones available within these relatively simple bundles of transistors. Let’s explore the origins of this versatile pedal, its varied incarnations, and what it might do for your music.

It All Started with a Broken Mixer

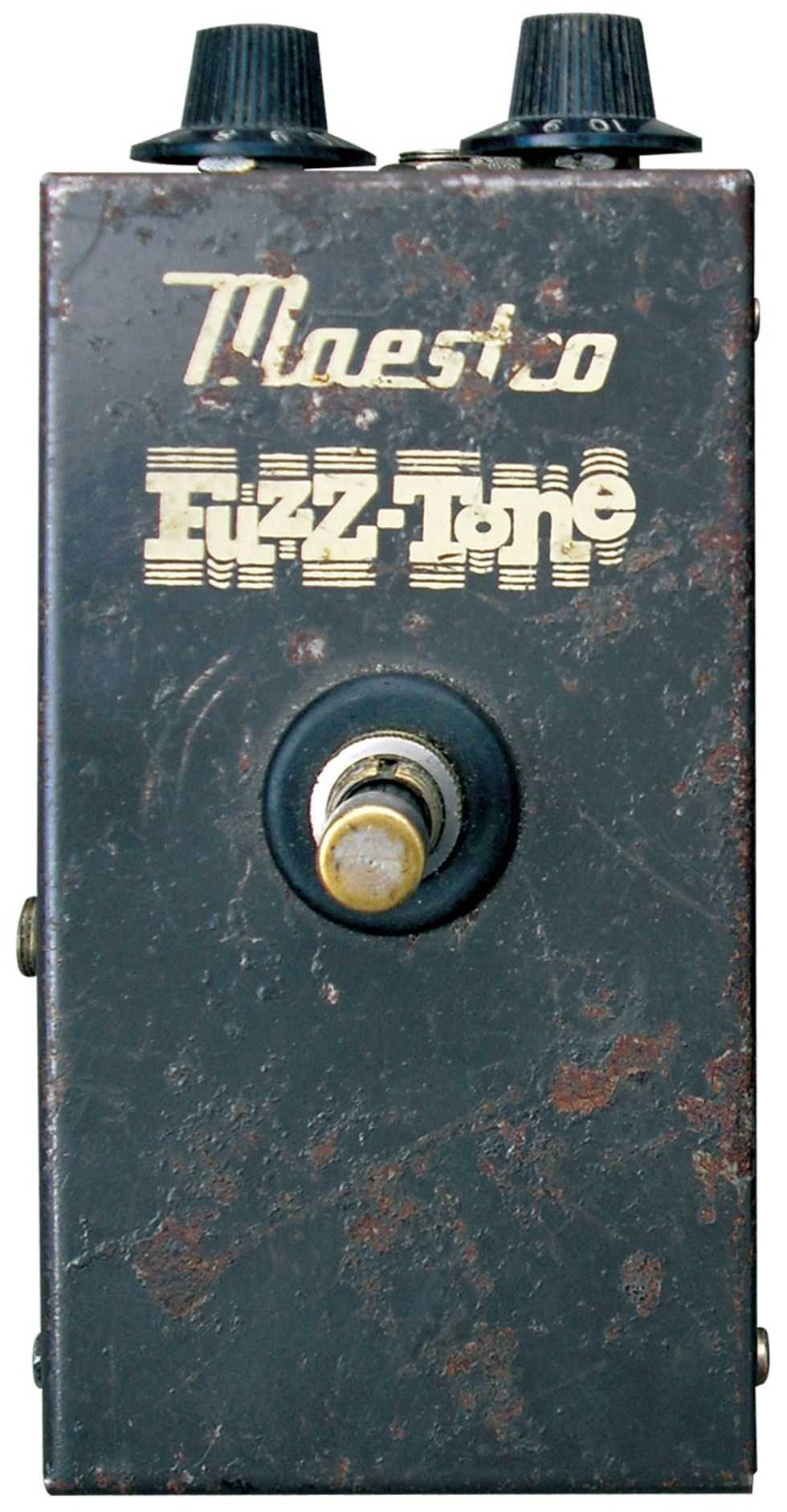

The history of the fuzz pedal really is rooted in guitarists’ quest for an enticing, dynamic distorted sound, and creative artists pursued this through several other means before transistorized boxes showed an easier way forward. Backtrack to the inspiration for the first commercial fuzz box, the Maestro Fuzz-Tone, and we land at one of those happy accidents that inspires a clever engineer and launches a sonic revolution.

Late in 1960, while recording Marty Robbins’ early 1961 hit “Don’t Worry,” Nashville engineer Glenn Snoddy noticed an odd—and yet quite divine—fuzzy sound coming from the channel of the tube mixer through which Grady Martin was recording his bass solo. The busted take stayed, becoming Nashville’s first recorded fuzz solo. Funky, farty and wild, the brief solo lends an air of “what the…?!” to an otherwise straight-up country crooner ballad, and the success of this out-there sound sent Snoddy in search of an easy way of recreating it on a regular basis. It’s worth noting that in the same year, California session musician and electronics wiz Orville “Red” Rhodes also developed a fuzz circuit for use in the studio. Although it was never produced commercially, he did build renditions for other guitarists on the scene, including Nokie Edwards of the Ventures, who used it on the band’s 1962 single “The 2,000 Pound Bee.”

Some early fuzzes were designed to emulate the rasp of a horn. In fact, Keith Richards’ famed fuzz riff on “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” was supposed to be a placeholder for a sax line that, thankfully, never got recorded.

Compacting that tube preamp down to a much simpler design using solid-state germanium transistors, Rhodes found success in the circuit that he would sell to Gibson affiliate Maestro, in 1962, to be manufactured as the Fuzz-Tone. The first British fuzz, the Sola Sound Tone Bender MkI, wouldn’t be released until the following year, and Maestro Fuzz-Tones were hard to come by in the U.K. that early on. Not that that stopped all British guitarists from acquiring the infectious sound. In 1964, the same year Dave Davies of the Kinks was abusing his amps to get there, guitarist Big Jim Sullivan—using a pedal custom-made for him by Roger Mayer—recorded a notable fuzz part on P.J. Proby’s hit single “Hold Me.” It’s largely a cheesy pop tune conceived to make teenage girls swoon, but the guitar solo that comes in at 1:30 exhibits a surprisingly thick and creamy lead tone and is really stand-out stuff for the era. Its no surprise British guitarists were chasing the sound the minute it hit the airwaves.

Soon after, artists were logging iconic fuzz-guitar tracks thick and fast. Keith Richards recorded the first genuine commercial fuzz-laced smash in May 1965 with the #1 hit “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” using a Maestro Fuzz-Tone acquired while the Rolling Stones were on tour in the U.S. That same year, a slew of guitarists used the British equivalent—the Tone Bender—to declare their allegiance to the new sound. Jeff Beck used a Sola Sound Tone Bender MkI to record the Yardbirds’ single “Heart Full of Soul,” which was actually released just before the Stones’ “Satisfaction,” but wasn’t quite as big a hit. And Paul McCartney, Mick Ronson, Pete Townshend, Jimmy Page, and several others plugged into Tone Benders the same year. The fuzz was out of the box, and there was no turning back.

Author Dave Hunter demos six different fuzzboxes to show you the flavors of filth.

Sola Sound was the first British manufacturer to offer a fuzz box, the Tone Bender MkI from 1965. Most Tone Bender models (including the MkI, MkII, MkIII, and MkIV) featured three germanium transistors, although the “Mk1.5” had two.

Early Production Units

Excluding early experimental units and one-offs from the likes of Mayer and Rhodes, commercial fuzz boxes really hit their stride in 1965 and ’66, by which time every music-electronics manufacturer worth their salt simply had to have a one on the market.

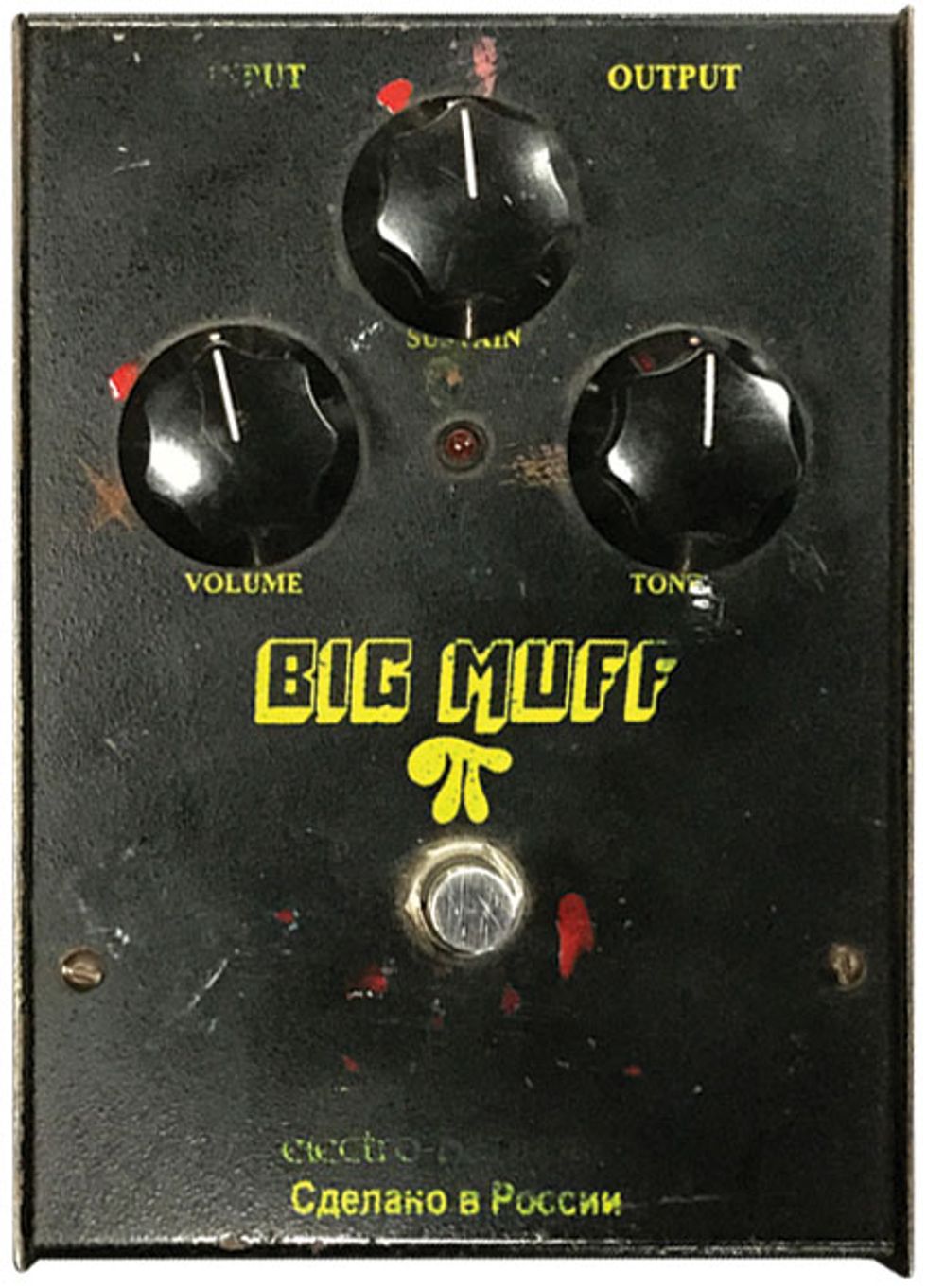

Although the concept had originated in the U.S., the U.K. was such a hotbed of creativity in the mid ’60s—both in terms of music and the gear used to make it—that far more new designs were springing from those shores, although several of the early units (including the Sola Sound Tone Bender) were largely copied from the Maestro Fuzz-Tone circuit. Significant early British fuzz boxes included the Vox V816, the Rangemaster Fuzzbug, the Arbiter Fuzz Face (Hendrix’s favorite, although his were often modified by Mayer), John Hornby Skewes’ Zonk Machine, WEM’s Pepbox, the Vox Tone Bender, the Baldwin-Burns Buzzaround, Marshall’s Supa Fuzz, Rotosound’s Fuzz Box, and the Selmer Buzz-Tone. Meanwhile, the U.S. saw the development of the Mosrite Fuzzrite and Sam Ash Fuzzz Box, although more would follow in the next year or two—notably with Electro-Harmonix founder Mike Matthews first supplying the Foxey Lady fuzz to Guild before releasing his own Big Muff Pi in 1969. And from there on out … good luck keeping up with the explosion.

Unforgettable Fur

It’s easy to see why the fuzz pedal became such a sensation early on, when there was no other means of achieving saturated distortion other than cranking up your amp to ear-blistering decibel levels. It’s impressive that the effect has continued to proliferate for more than 50 years, though—even in the face of more realistically tube-like overdrives and multi-channel, high-gain amps with effective master volume controls that allow fully tube-driven lead tones at more reasonable volumes. The fact remains that, when used well, fuzz slathers the guitar in an infectiously rich and textured soundscape that really can’t be achieved in any other way, or at least not as simply as plugging into one of these minimalist boxes.

Although fuzz was first developed to imitate distorting tubes, it was often seen by the marketing departments of early manufacturers as a means of enabling guitarists and bassists to imitate the razz and rasp of a horn player. Hence the names that adorned some models, like the Maestro Bass Brassmaster and the Roland Bee Baa (which takes us full circle to Keith Richards’ use of the Fuzz-Tone on “Satisfaction,” with which he recorded a guitar line that was originally just intended as a holding place for a horn part that never happened).

The pedal’s greatest efficacy became, though, its ability to help push a good amp to where you wanted to get it. More tone-conscious early proponents—Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton, and Jimmy Page among them—soon learned to incorporate fuzz into a well-blended sonic stew in which the device helped push an on-the-edge tube amp into luscious overdrive, rather than jumping out as an effect in its own right.

Some of the better latter-day users of the circuit exemplify why fuzz remains so addictive. Listen to the irresistibly thick, juicy pillow of tone that Dan Auerbach achieves on Black Keys songs like “Lonely Boy” or “Money Maker,” or the relentless granular grind of Fu Manchu’s “Evil Eye,” and you hear sounds that are really only achievable via a good fuzz pedal. Put another way: Fuzz might have proved a means of imitating a cranked tube amp early on, but it has long since established its own thing—something that even cranked tubes can’t match.

From Subtly Dynamic to Utterly Unhinged

Part of the beauty of a good fuzz pedal is that, while it can be used to create some extreme noise, it also allows a lot of dynamics and player control when used judiciously. While the most popular fuzz circuits contain two (Fuzz Face), three (Tone Bender), or four (Big Muff) transistors—the components responsible for the bulk of the “clipping” or distortion—the more austere versions can be made with a total of 10 components, so there often isn’t a whole lot going on inside a fuzz box.

The British engineer Roger Mayer, who built early custom fuzz pedals for several notable guitarists and for a time was guitar tech for Jimi Hendrix, put it to me like this: “A simple circuit, if it’s designed in a certain way, becomes a very complex thing, analytically. It becomes organic, so the actual sound itself then begins to take on a human quality, because quite naturally you are taking information from the guitarist’s playing technique or from the input, and that’s control in itself, determining its own output. It hasn’t had an algorithm or a set of parameters placed on it to predetermine the sound [the way a digital effect has].”

Jimi Hendrix preferred the Arbiter Fuzz Face, which took his amp’s tone to new places and allowed his inimitable touch to remain intact, thanks to the device’s responsiveness to pick attack and other factors.

So Mayer is saying that much of the beauty of a good fuzz is in its controllability—that it can be “played,” or controlled, according to the strength of the player’s pick attack or the setting of his or her guitar’s volume control. This is one of the fundamental characteristics that makes a good fuzz pedal amenable to use in virtually any style. Pick lightly or dial down your guitar’s volume, and many of the better fuzz pedals will clean up to a surprising degree, retaining a juicy thickness in the guitar tone, yet without the inherent fuzz and outright distortion that the effect was made to produce. That, according to Mayer, is when “it takes on an organic quality, a very human type of sound. All that stuff that was done with Jimi on all the records, even the stuff that was very distorted, it was very human sounding.”

On the other hand, bend a fuzz beyond what it was intended to do and you can produce some extremely creative and expressive sounds. In addition to the balance between gain (a knob also often labeled “fuzz” or “sustain”) and output levels, the variables between other internal parameters can greatly affect the character of a fuzz pedal’s sound. To tap into these variables, creative makers are adding controls to govern things like transistor bias settings, battery condition, modified EQ filtering, added booster stages, and to simulate over- or under-spec components, the manipulation of which can change the sound of what is otherwise a known classic—a Fuzz Face or a Big Muff, for example—into something wild and unrecognizable. ZVEX was one of the first makers to do this in a successful production model with its Fuzz Factory, and several other pedals have gone that route since: notably the Blackout Effectors Musket Fuzz, EarthQuaker Devices’ Hoof, Epigaze Audio’s Singularity Expanded Vintage MkII, and the Death by Audio Supersonic Fuzz Gun, among others. Meanwhile, the Fuzz Factory itself went further over the top in 2016 as the Fuzz Factory 7, with added control parameters.

Twist the gate and comp knobs on a ZVEX Fuzz Factory, and you can take the pedal from smooth and thick to spitty and harsh to glitchy and verge-of-death sounding, recreating the otherwise accidental freak tones produced when a pedal’s battery is losing voltage or its transistors are improperly biased. Tap these intentionally and bend them to your own creative ends, and you’ve got a pedal that’s exponentially more expressive than the standard fuzz.

Author Dave Hunter demos six different fuzzboxes to show you the flavors of filth.

The Fuzz Factory, from ZVEX, was among the first modern germanium-based dirt pedals to incorporate more complex controls and expand the potential of the effect.

Germanium Warfare

The fuzz boom of the mid ’60s was enabled by a boom in transistors. These compact, solid-state amplification devices made it possible to design sonic circuits that would have been unfeasibly cumbersome to achieve with tube technology. These early transistors were made with a chemical element called germanium—a silvery-white metalloid that is part of the carbon family and acts as a semiconductor when correctly harnessed in an electronic circuit. Fans of the earliest vintage fuzz pedals swear by the sonic properties of germanium transistors, which tend to be a little softer sounding and more compressed than the silicon transistors that proliferated by the late ’60s. As a result, players often cherish these early pedals, while many makers continue using germanium transistors in contemporary designs.

The granddaddy of fuzz pedals, the Maestro Fuzz-Tone, used three RCA 2N270 germanium transistors, while most versions of its British semi-equivalent, the Sola Sound (later Colorsound) Tone Bender, also carried three germanium transistors in the interesting combination of one Mullard/Phillips OC75 and two Texas Instruments 2G381s. Many other classics, however, including the Sola Sound Tone Bender “Mk1.5” and the Arbiter (later Dallas-Arbiter) Fuzz Face, were made with only two germanium transistors. In the Fuzz Face’s case, it was usually NKT275s or AC128s. According to Dan Coggins, designer of the legendary Lovetone pedals of the mid to late ’90s, “Although they [the NKT275 and AC128] are both germanium, they do sound slightly different because of the geometry of the construction inside them. I’ve fiddled with old Fuzz Faces that I’ve fixed for people, and I’ve put in AC128s [in place of NKT275s] because that’s all I could get … and they certainly sounded different, though I don’t know if they sounded better. It all depends.”

It’s worth noting that fuzz fiends can easily go down the rabbit hole chasing the supposed “sounds” of specific makes of germanium transistors, but, while transistors can influence circuits differently, it’s always worth trying any pedal as a whole before deciding you must have the particular traits of one type of transistor or another. Nevertheless, there’s little argument that good germanium transistors can do something that just isn’t easily achieved without them. That said, transistor type is really a matter of horses for courses: Plenty of great tones can be achieved with non-germanium components. While germanium transistors are essential to ZVEX’s Fuzz Factory and Fuzz Probe, for example, Zachary Vex tells us, “I’m not absolutely hung up on the concept of germanium being the be-all and end-all for fuzz. I mean, there’s an awful lot of fuzz textures.”

Along with their appealingly organic sound, germanium transistors can exhibit wide swings in tolerances, meaning any two—or 10—coming off the assembly line side by side rarely sound exactly the same. Aware of this phenomenon, good latter-day makers test and sort germanium transistors to find those that perform as desired. As Roger Mayer told me, “The reality is that you’ve got to buy thousands of them. Then you’ve got to sit down and test them all, and you’re only going to come up with a small percentage that are any good.” Manufacturers in the ’60s and early ’70s didn’t go to such trouble and tended to load in transistors semi-randomly. As a result, early fuzz pedals that used them could sound quite different. Players hip to these wide swings understood that they often needed to try 10 or 20 Fuzz Faces or Tone Benders to find the best-sounding examples among them.

The Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi was one of the first silicon-transistor-based fuzz pedals and remained so from 1969 through the Sovtek era to the present day—save for some special editions, like the EHX Germanium 4 Big Muff.

Germanium transistors also react to temperature, often sounding optimal when cooler and losing composure a little as they heat up. “You should stick your germanium Fuzz Face-type pedal in the fridge,” Vex laughs as he only half-jokingly advises an experiment. “Leave it in there for a few hours, take it out, plug it in, and listen to the way it changes as it warms up—because it’ll change a lot. The gain on the transistor will change almost by double, depending on the temperature range.”

Silicon Valley

The advent of silicon transistors in the late ’60s brought tighter tolerances to these small components, and a more consistent performance to the pedals that contained them. They also changed the inherent sound of these circuits somewhat. While many players mourned the absence of specific qualities of germanium transistors—arguably heard as a rounder, more musical sound—others dug the attack and aggression that silicon brought to these pedals, and found it just right for the heavier forms of rock that evolved from the late ’60s into the ’70s.

Fuzz Faces started to incorporate silicon transistors in 1969, and around this time many other makers started switching to silicon, too, simply because they were touted in the industry as being more rugged and more consistent. Electro-Harmonix’s Big Muff Pi was a silicon design right from the start. And for all the talk of silicon fuzz pedals being edgier and more harsh, with more jagged clipping when pushed into distortion, they can certainly be used to create extremely warm, round, musical guitar tones when desired. It’s telling that tone hounds like Eric Johnson and Joe Bonamassa have long preferred silicon fuzz pedals. Ultimately, there’s a huge variety in silicon fuzz pedals, too, and this later (if only slightly) technology accounts for a larger swathe of today’s fuzz market than germanium transistors do.

Several makers also provide the opportunity to sample the differences between silicon and germanium in circuits that are otherwise similar. Analog Man, for one, makes several renditions of the Sun Face fuzz, a Fuzz Face clone, using various types of germanium and silicon transistors—the germanium Sun Face AC128 versus the silicon Sun Face BC183, for example. Jim Dunlop manufactures several iterations of its current Fuzz Face using germanium and silicon, and Fulltone offers both the ’69 MkII and the ’70-BC, which use germanium and silicon, respectively. Some other components usually vary, too, reflecting changes necessary to optimize each particular circuit, but these pedals do provide at least a semi-accurate A/B experience of the two technologies.

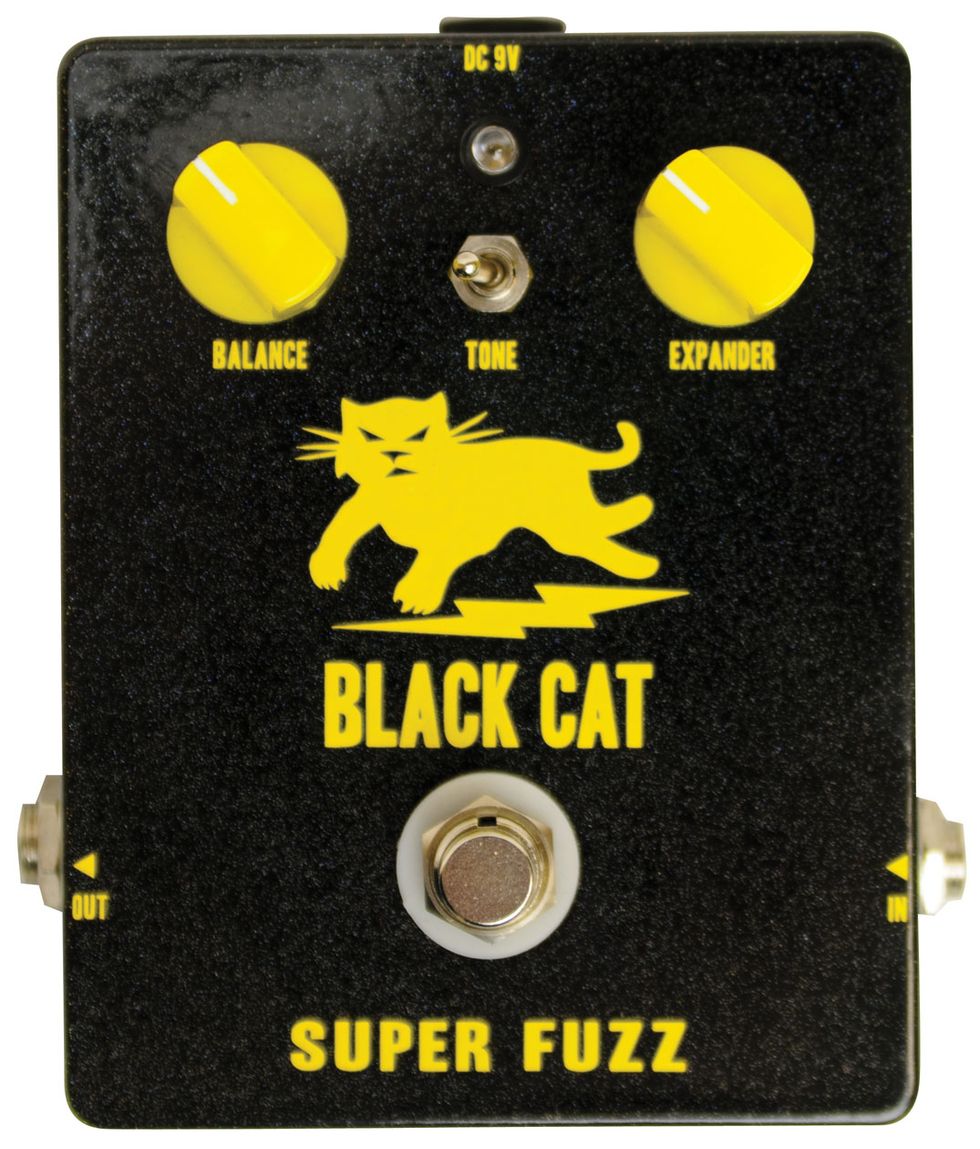

Several modern pedals, including the Black Cat Super Fuzz, are designed to emulate the widescreen sounds conjured by the Univox Super-Fuzz, which was Pete Townshend’s go-to box from the late ’60s to late ’70s.

Alternative Tech

Although germanium and silicon represent the classic fuzz dichotomy, other forms of technology have been used to create that sound. In 1978, Electro-Harmonix released the Big Muff Pi V4 using op amps (which later proliferated in standard overdrives and other types of pedals), while some makers have also included diode and LED clipping stages to achieve different ends. The latter—seen in stompboxes such as Keeley’s Psi Fuzz (which also uses an op-amp stage), the Black Arts Toneworks Pharaoh Supreme, and El Rey Effects’ Mystic—is generally intended to voice the character of the overall distortion, often to smooth out the potentially fizzy highs that some circuits might otherwise display.

Then and now, though, other alternative approaches blend a variety of technologies to come at the whole thing somewhat differently, yet resulting in an effect that’s still heard as fuzz. The Univox Super-Fuzz, for example—the choice of the Who’s Pete Townshend from the late ’60s to the late ’70s, and now a major cult favorite (popularly recreated today by Black Cat as the Super Fuzz)—uses several transistors to create and blend both fuzz and subtle octave-up effects, with added square-wave-clipping fuzz over the top from a pair of germanium diodes.

Tackle the Tone

Having covered the history and the tech, it really just remains to say get out there and try some fuzz! Given the immense diversity of fuzz pedals, and the vast range of sounds they can help you achieve, there’s really no reason to exile these pedals into the narrow stylistic box in which many players constrain them. Experiment with the subtleties, the extremes, and some of the classic sounds in between while integrating fuzz into your rig the way it was intended: as an extension of the guitar-to-amp connection, rather than a stylistic brick wall.

Whether it’s used to propel new-age blues raves like Jon Spencer Blues Explosion’s “Soul Trance” or Gary Clark Jr.’s “When My Train Pulls In,” or for mammoth grunge like Smashing Pumpkins’ “Cherub Rock” or Fu Manchu’s cover of Blue Öyster Cult’s “Godzilla,” or more experimental, otherworldly, yet still inherently musical sonic excursions like Sonic Youth’s “Starfield Road” or Dead Meadow’s “Sleepy Silver Door,” a good fuzz pedal can very likely open up new creative worlds for you, too.

Author Dave Hunter demos six different fuzzboxes to show you the flavors of filth.

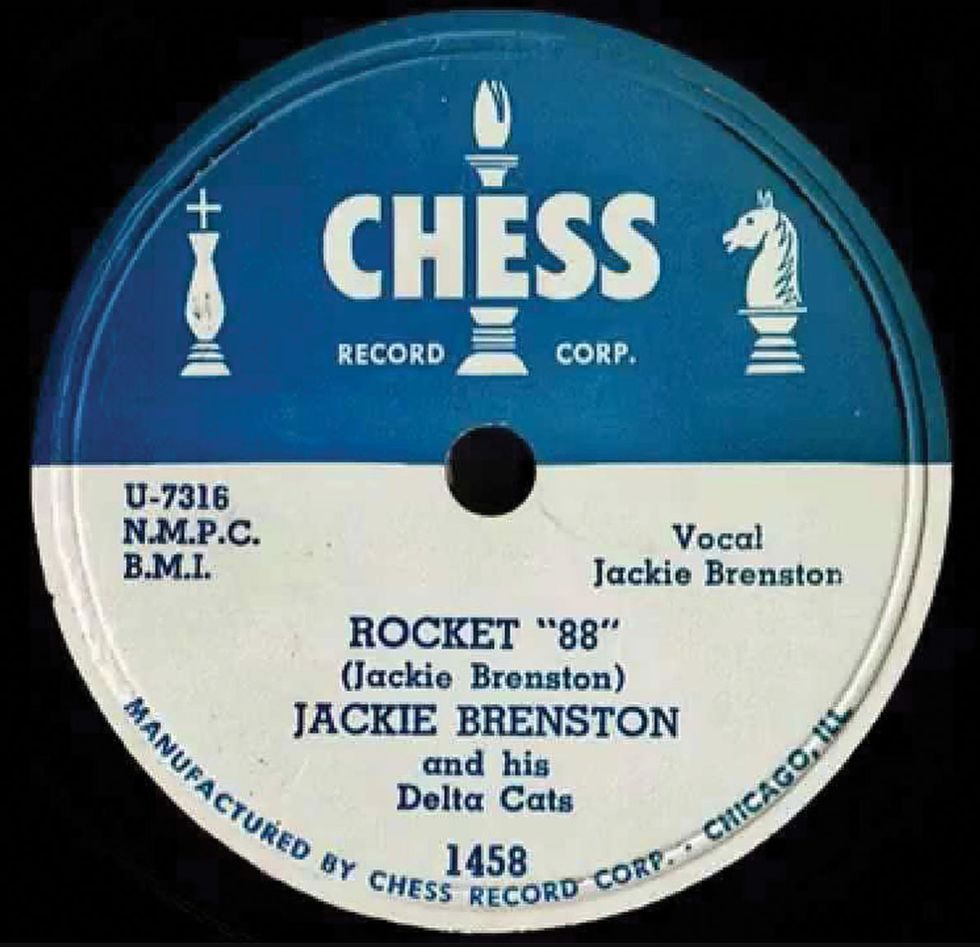

With the 1951 release of Ike Turner’s “Rocket 88” and its scuzzy guitar track, the history of rock ’n’ roll

and fuzz were forever entwined.

Early Distortion: Busted Tubes and Slashed Speakers

Although Glenn Snoddy’s clever little bit of alchemy led to the first widely disseminated solid-state fuzz box, the sound of distorted guitar (or even bass) was nothing entirely new when it landed Marty Robbins’ a hit record in 1961. Many blues guitarists had been pushing their tweed-era tube amps into juicy overdrive for years, and other crazy flukes had yielded some wild tones that proved as irresistible as the sound of the busted mixer channel.Rewind to a rainy night in Memphis in 1951, when—according to legend—someone dropped the band’s Fender amp while Ike Turner & His Kings of Rhythm were loading in for a recording session with producer Sam Phillips. Whether it was the fall or the rain that got into the circuit, the amp popped a tube during power-up at the studio.

As a result, one of the songs from that session, “Rocket 88”—credited to R&B singer/saxophonist Jackie Brenston and His Delta Cats, though the Cats were really Turner and his band—was underpinned by the distorted guitar of Willie Kizart. That sound helped “Rocket 88” enter the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, honored as the first rock ’n’ roll song and forever tying distorted electric guitar to the genre’s first days.

Even in the early to mid ’60s, the fuzz box was brand-new tech, and not everyone was aware of it or had access. Guitarist Dave Davies of the Kinks famously went to the extreme lengths of slicing the speaker cone in his little Elpico amplifier—perhaps inspired by the holes Link Wray poked in his amp’s speaker to record 1958’s “Rumble”—to record the gnarly, ragged guitar track on the band’s 1964 hit “You Really Got Me.” A fuzz box would have saved him some trouble, although there was no U.K.-made commercial unit available until the Sola Sound Tone Bender of 1965.

Clip 1—Dry Guitar (No Fuzz)

0:00 – Bridge pickup dry0:22 – Neck pickup dry

0:36 – Neck pickup dry, then with guitar tone down to “0” (all fuzz samples will also have a clip played with the guitar dialed in like this).

Clip 2—Blackout Effectors Musket

0:00 – Bridge pickup; Pre-55%, Mids-60%, Focus-45%, Fuzz-60%, Tone-60%, Vol-60%0:35 – Neck pickup; Pre-70%, Mids-10%, Focus-75%, Fuzz-90%, Tone-75%, Vol-60%

1:08 – Neck pickup, guitar tone at “0”; fuzz settings same as 0:35

Clip 3—ZVex Fuzz Factory

0:00 – Bridge pickup; Volume-30%, Gate-50%, Comp-60%, Drive-70%, Stab-45%0:35 – Neck pickup; Volume-30%, Gate-60%, Comp-50%, Drive-90%, Stab-75%

1:09 – Neck pickup; guitar tone at “0”; fuzz settings same as 0:35

1:40 – guitar tone back to “10”, settings start as 1:09, but knobs actively twisted…

Clip 4—Black Cat Bass Octave Fuzz

0:00 – Bridge pickup; Bass-60%, Drive-60%, Fuzz-60%; Filter Sw-left, Harmonic Sw-left0:32 – Same settings as 0:00 but: Filter Sw-right

1:08 – Neck pickup; Bass-60%, Drive-100%, Fuzz-60%; Filter Sw-right, Harmonic Sw-left

1:39 – Neck pickup, guitar tone at “0”; Bass-60%, Drive-100%, Fuzz-60%; Filter Sw-right, Harmonic Sw-left

Clip 5—Black Cat Super Fuzz

0:00 – Bridge pickup; Balance-60%, Expander-60%, Tone Sw-left0:27 – Bridge pickup; Balance-60%, Expander-60%, Tone Sw-right

0:57 – Neck pickup; Balance-90%, Expander-55%, Tone Sw-right

1:30 – Neck pickup, guitar tone at “0”; Balance-90%, Expander-55%, Tone Sw-right

2:02 – Neck pickup, guitar tone at “0”; Balance-90%, Expander-55%, Tone Sw-left

Clip 6—Roger Mayer Spitfire Fuzz

0:00 – Bridge pickup; Output-60%, Drive-60%0:33 – Bridge pickup; Output-50%, Drive-100%

1:23 – Neck pickup; Output-50%, Drive-75%

1:55 – Guitar tone at “0”

2:18 – Bridge pickup, guitar tone at “0”; Output-60%, Drive-60%

2:31 – Guitar tone at “10”

Clip 7—Jim Dunlop Eric Johnson Signature Fuzz Face

0:00 – Bridge pickup; Volume-50%, Fuzz-50%0:32 – Bridge pickup; Volume-45%, Fuzz-100%

1:20 – Neck pickup; Volume-45%, Fuzz-100%

1:46 – Guitar tone at “0”