“I definitely lean toward extravagant, psychedelic guitar playing,” says Ty Segall. “I like weirdos.” Photo by Denée Petracek.

Ty Segall isn’t your typical guitar geek. “I was the kid who learned by listening to Black Flag, playing two-finger power chords,” he concedes somewhat sheepishly with an undeniably Californian twang. But get on the subject of 1960s psychedelic space rock or percussive acoustic guitar craft, and Segall is ready to take you to school.

Since 2008, Segall has been channeling his inner Zappa, pumping out records by the fistful and embracing a singularly eclectic style. Segall’s latest, Manipulator (Drag City), is a heady brew that mashes sunbaked psychedelic melodic strains with Blue Cheer-meets-Blue Öyster Cult riffs and the acoustic jangle of Zeppelin and Sabbath.

A preposterously prodigious songwriter, Segall is no slacker when it comes to playing, having tracked nearly all the instruments and vocals on Manipulator. From janky-sounding acoustic tracks to trashy, thrashy lead parts, Segall sounds completely at ease with a guitar in his hands, no matter which other hats he might be wearing.

How did this batch of songs come together?

The songs on the record come from 14 months of writing. I spent the whole year writing at my house, two-to-seven days a week, depending on what was going on. The ones that made the record are just the best of the bunch.

Do you have a songwriting regimen?

It takes a lot of work to get to the point where you’re not working too hard for it. It takes a lot of discipline—doing things every day just to do them. If you get one good song per week, you’re really lucky. But you can work for a month or two without getting a single good song.

How do you keep track of your song ideas?

I record ideas. There are lots and lots of songs I’ve thrown away through the years: Multiply my discography by three, and you get an idea of all the songs I’ve thrown away!

Do you know immediately if something isn’t working, or do you get outside opinions on that?

There have been a couple times when I’ve written something I thought was garbage, but other people felt I should put on a record. Most of the time, I just know. If it feels like a put-on, pushing an emotion, or relying on a gimmick or a specific sound, that’s not right.

What are your attitudes about collaboration in your songwriting?

I love collaborating. My favorite kind is the rapid-fire, open-minded freestyle where it’s as if you’re passing a ball back and forth. It’s a very good way to refresh your own mind in songwriting.

Ty Segall’s live band for the Manipulator tour includes Charles Mootheart on guitar and Emily Rose Epstein on drums. Mikal Cronin handles bass (not pictured), but pictured here on bass is Denée Petracek. “Everybody in the band rips, so to take the songs into a less-controlled place

is pretty amazing,” Segall says.

When you’re writing, how do you record those ideas?

I have a Tascam 388 8-track at my house, and I just demo songs out like they would be for a record. It’s not just to write it, it’s testing a song’s ability to be on a record. If it doesn’t work, I might try another version. For some songs on Manipulator, there were three or four versions of a demo.

Do you think in terms of songs or in terms of albums?

You have to start by thinking in terms of songs. If you think purely in terms of an album, the songs just aren’t going to hold up. I’m an “album guy,” so I like to try to have both in mind.

Do you think of Manipulator as having a unifying thematic or sonic thread running through it?

Yeah, thematically, all those songs rest in the same place—lyrically, they’re in the same world. They’re like characters that interact with each other, and there’s a loose story being told.

Two of my favorite albums are Electric Ladyland [Jimi Hendrix Experience] and The Beatles [aka “the White Album”]. Those are both double records but each of them is very varied—they don’t have a unifying sonic element, and that’s what makes them unified. It was a similar idea with Manipulator.

Ty Segall plays his No. 1 preferred model, a Fender Mustang. He’s recently taken a Les Paul on the road as a workhorse. Photo by Jackie Roman.

Do you write on guitar, or come up with drum patterns first, or all of the above?

All of the above. I find it helps to mix up how you start a song, and where the idea comes from. That’s crucial to keep something new sounding. If a song is written on drums first, with a melody in your head, it’s going to be a way different song than if it were written on guitar.

When do lyrics come into play?

I usually do lyrics at the same time when I’m writing on guitar. But with drums, it’s completely after-the-fact, freestyle.

What about stages of tracking? What goes down first?

On the demos, I might track guitar first, but when it came time to do the record, I always would track the drums first, to make sure they sound perfect. Then I would do bass, guitar, keyboards, and always vocals last.

Do you write down an arrangement or is it in your head?

I’ll just make notes as we go along. Like, “Needs noise blast at 0:32.”

Who are some of your guitar heroes?

For acoustic, I’m a huge John Fahey fan, because he’s weird—he’s bizarro. He’s super emotive, but also rhythmic. It’s especially important to be rhythmic when it comes to acoustic playing—the percussive clashing of the pick on the strings is one of my favorite things. You can get that with fingerpicking, too. I love when someone smacks an acoustic with their palm—it’s great!

I also love the old blues guys, and so many great electric players are also great acoustic players—Hendrix, Jimmy Page, all those guys.

When it comes to lead guitar players, who gets you most amped?

Oh, man … Tony McPhee of the Groundhogs, for one. Along with the guys in Pink Fairies and the guitarist for Hawkwind—he was part of the crew of early-’70s English, post-psychedelic, hard-rock guys. He played with a lot of blues guys and started going into a lot of weirder hard-rock stuff. I love him.

Peter Green is super cool, [Frank] Zappa is crazy—Hot Rats is so fun to listen to. And then there are the classics: Tony Iommi … Jimmy Page is so rad. It’s cliché to talk about him, but there’s a reason why: He’s so great! He’s so interesting—that’s what it is about him. I also like Bob 1 [Mothersbaugh] from Devo, who’s super weird and cool.

Ty Segall's Gear

Guitars

1966 Fender Mustang

1977 Gibson ES-335

1970 Gibson Les Paul

1970s Italian-made acoustic 12-string

Stella acoustic guitar

Amps

1972 Fender Quad Reverb

Music Man HD-130

Effects

Death By Audio Fuzz War

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL115 (.011–.049)

Bass Gear

1968 Gibson EB-0 with flatwounds

1970s Ampeg B-15

I really like lead guitarists who don’t need to play in your face, they just add a really nice accompaniment to things. There’s also Randy Holden, who was the second guitar player in Blue Cheer. He’s on the third Blue Cheer record [New! Improved! Blue Cheer]. He’s only on the B-side, because they kicked him out—he was too good! [Laughs.] He was pretty rad. And then he put out a solo record, Population II, that’s absolutely insane, with the coolest leads ever. I definitely lean toward extravagant, psychedelic guitar playing. Steve Morgen is another. I like weirdos.

What are your go-to guitars?

My main squeeze for a long time was a ’66 Fender Mustang that I toured with and recorded with for years. But the idea with this record was to mix it up. So I got a ’77 Gibson ES-335, which is what I used on a lot of the rhythm tracks for Manipulator. A lot of the leads are the Mustang. I have just one amp I like to record with—a ’72 Fender Quad Reverb. It’s like a double Twin with four 12" speakers.

Wow, that must be pretty heavy.

Yeah, but it breaks up in the best way ... it sounds like Dick Dale on steroids.

Those kinds of amps are popular among players who want clean sounds. You can get it to break up without going deaf?

Well, I definitely play way too loud! [Laughs.] But it has gain and master volume knobs, so you can kind of control things.

What about effects?

I have a Death By Audio Fuzz War pedal, which is pretty much the only pedal I like using these days.

Do you have a string preference?

I like to play .011 sets. Ernie Balls are rad, but I’ve been switching around a bit. I played Ernie Balls for a really long time, then I switched to D’Addarios, which I’m trying out right now.

What are you looking for in a string set?

I just want the toughest strings out there that aren’t going to break. I break strings every other show if I don’t change them. It’s super annoying. One issue is that Fender Mustang bridge….

Do you use the tremolo on the Mustang?

So much—it’s kind of stupid how much I use it.

Aside from their floating tremolo bridges, Mustangs are quirky when it comes to the pickup phase switches.

When I want to play the Mustang, I just set it with the bridge pickup on “rhythm,” because it has so much treble to begin with. And then on my amp, I’ll turn every tone knob up to 10.

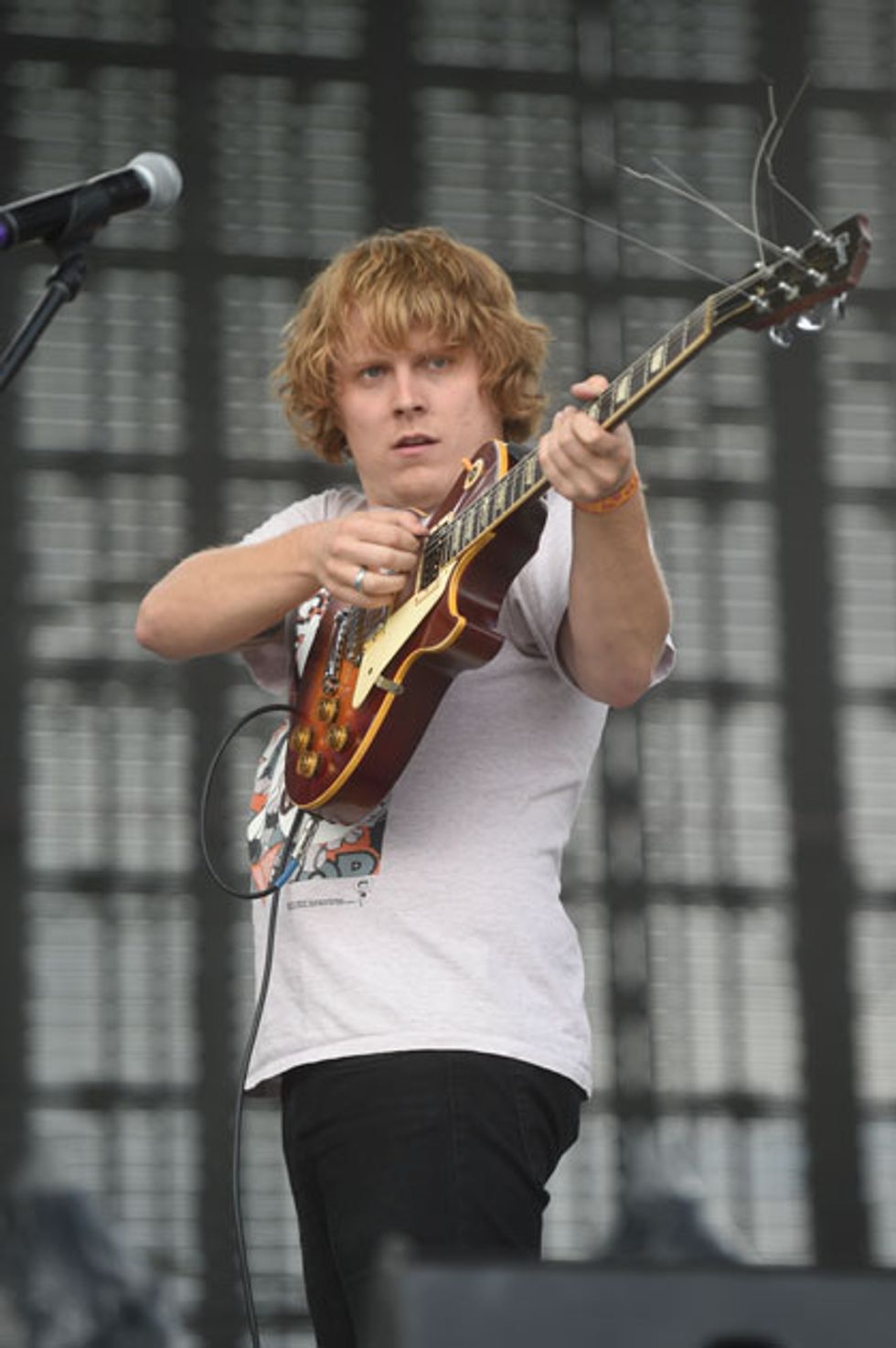

Segall plays his 1970 Les Paul on August 16, 2014, at the Ceremonia festival in Toluca, Mexico. He got the guitar at a bargain price because of its repaired headstock. Photo by Tony Franćois.

Is there any other guitar gear that’s getting you excited these days?

I didn’t want to bring my hollowbody on tour, so I got a 1970 Gibson Les Paul for the road. It had a broken headstock, but that was fixed around 1975 and has been fine ever since. That’s cool, because that made it cost about $2,000 less than it should have!

What about the acoustic guitar on Manipulator?

A lot of it is 12-string. I have an old Italian 12-string from the ’70s. Live, it sounds dead—it’s backwards and wrong. But it records perfectly. It sounds like cardboard, which is great. You turn up the mic and there are no weird low-mid frequencies, which can sometimes be a problem. I also have a really nice Gibson 12-string acoustic. But recorded, it sounds like shit. I also have a Stella acoustic guitar that sounds really bad live. But recorded, it sounds great. Those are the two acoustic guitars on the record.

What’s going on in the bass department?

I have a ’68 Gibson EB-0 bass. With its short scale, that one is super fun to play. The action on this one is super low, so I can do crazy stuff on it.

What about bass strings?

I’m a fan of flatwound strings.

How do you amplify your bass?

I usually play it through my Fender Quad—I don’t have a designated bass amp. But for this album, I borrowed my buddy’s ’70s Ampeg B-15.

The bass tone on “Feel” is especially gnarly. What went into that?

Ah, there’s a secret on that one! We sped up the tape machine, and I played guitar as the bass line. We then put it back to normal speed so it was an octave lower. Then it was mixed with an actual bass track, which gave it a particular sound.

You get a sick, crunchy rhythm guitar tone on songs like “The Faker” and “Susie Thumb.” Is that your Gibson ES-335 in action?

Yes, often through the Fuzz War pedal.

What’s your approach to using fuzz pedals on rhythm guitar tracks?

The way I see it, all that breakup and noise works like cool blemishes on the record. Put very simply, I’ll think: The verse is clean, the chorus is fuzzy. Rhythm and lead guitar parts often work the same way.

And your strategy in terms of creating memorable guitar solos?

I view myself as playing two different types of guitar solos: the melodic hook solo, and the noisy weirdo solo. It’s all about having perspective and being appropriate. But all of that stuff is like taking a ball of paint and throwing it against the wall.

That probably doesn’t work every time.

Oh, not at all. But you work through it and you reach another place where you “get it.”

What about playing live?

It’s different live, because the songs change and become entirely different beasts. It’s all part of a song becoming “finished.”

YouTube It

Ty Segall and his band slay it on Conan, performing “Feel” off his new album, Manipulator. Forward to 1:50 for a freak-out solo!

Who’s in your live band?

Charles Mootheart is the other guitar player in the band. He’s a madman—a far better guitar player than I am. He’s the guitar player in my other band, Fuzz, where he’s the main riffmaster. He used to play Fender Mustangs and now he plays a custom guitar. He uses a Fuzz War, as well, and he plays through a Music Man 4x10 amp, and a Fender Twin head through a 4x12 cabinet.

Live, I play my Fender Quad Reverb and a Music Man head through a 4x12 cabinet. We both play through two amps.

On bass, you have Mikal Cronin. What gear does he use?

He plays a Rickenbacker through a giant [Ampeg] 8x10 cabinet.

Given that you tracked most of the parts on Manipulator, how do these other players get you psyched?

That’s the coolest part of it all: We’re all learning it together as a band. And as a band, I think we’re generally louder, faster, and a bit more aggressive. That’s exciting to me, especially when tackling songs that were written in a more controlled environment. Everybody in the band rips, so to take the songs into a less-controlled place is pretty amazing.

How involved are you in steering the overall sound of the ensemble onstage?

The way I see it, my role is in setting the tempo and the chord changes. That’s it. With a band, some things will take on a different vocal harmony, vibe, etc.

Aside from the band, what have you heard this year that gets you excited to play?

I’ve always been a total record junkie-nerd-weirdo, rummaging through records for new discoveries. Lately, I’ve been overloaded with stuff, such that I’m continuously buying records.

Also I’m really fortunate to know a lot of great players—Mikal has some solo records that are insane and great, along with the band White Fence, which I just worked with. The cool thing is that everybody’s pushing each other all the time, but there’s no negativity and harshness—it’s positive and helpful. It’s like a friendly competition, which is cool.