Thanks to its mechanical “converter comb,” this 1967 Rickenbacker 366/12 can be played as a 12-string or a 6-string—or something in between.

The flattop 12-string guitar was a foundation of the folk music movement of the early ’60s, and this inspired Rickenbacker to design and manufacture an electric 12-string in 1963. Although other companies (notably Gibson and Danelectro) had made earlier attempts, the Rickenbacker 12-string electric became the most sought-after because of its association with George Harrison of the Beatles.

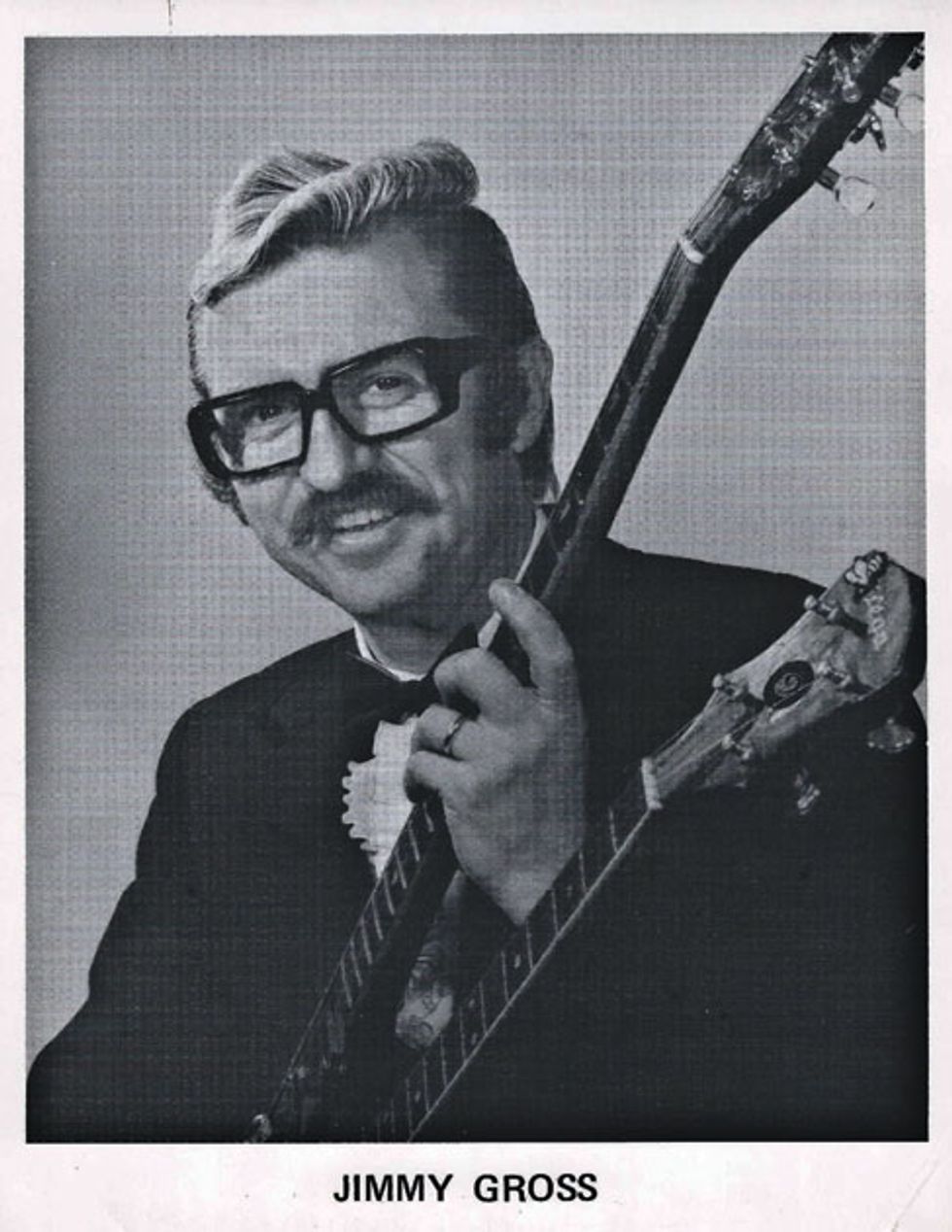

Musician and inventor James E. Gross was intrigued by the electric 12-string and decided to put his imagination to work on improving it. Born in 1931 in Lafayette, Indiana, Gross began playing music professionally at a very young age. He was distinguished as a performer and bandleader in the Chicago area for many years, and was known for playing unique double-neck banjos and combining comedy with exploding light shows and robots.

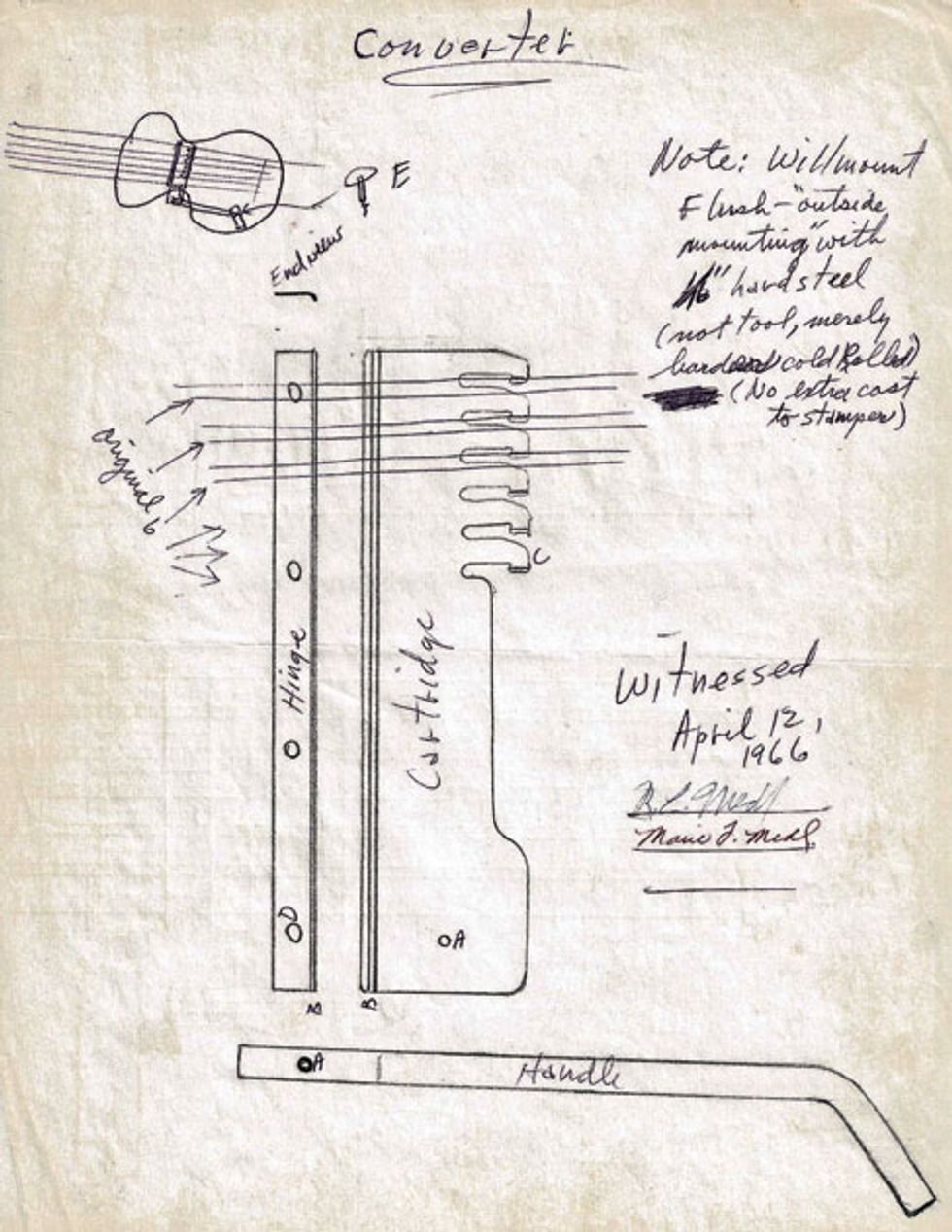

In 1966 Gross approached Rickenbacker’s owner F.C. Hall with his practical, easy-to-install converter device. This “converter comb” could turn a 12-string into a 6-string (or any number in between). When the converter was engaged, it pulled strings down away from the player’s right hand, leaving only the desired number of strings to be picked. Gross demonstrated the converter at the July 1966 NAMM show. A licensing agreement was signed in August, and the guitars went into production by winter.

The models produced were the 336/12, 366/12, and 456/12. The original Rickenbacker advertisement copy read: “Now, one instrument—the most versatile guitar ever made—ends the need for carrying extra guitars. By means of an exclusive, patented converter on the brilliant Rickenbacker 12-string guitar, any combination of strings can be played.”

The 1967 366/12 pictured here was James Gross’ personal guitar. It has most of the features associated with classic Deluxe Rickenbacker models of the ’60s. These include a bound maple neck, a gloss-finished rosewood fretboard with large triangle-shaped inlays, two “toaster” single-coil pickups, a maple body with checkerboard binding on the back, a slash soundhole, and an “R” tailpiece.

This example is finished in Rickenbacker’s most popular color, Fireglo. The main differences between it and a regular 360/12 are the chrome converter comb and the extra pickguard under it, which extends below all 12 strings. The 1966 list price was $579.50. The current value for one in excellent all-original condition is $4,500.

The 366/12 rests against a late-’60s Rickenbacker Transonic TS100 amp. The Transonic’s current value is $1,000.

Sources for this article include Tony Bacon’s Rickenbacker Electric 12-String and The History of Rickenbacker Guitars by Richard R. Smith.

A very special thanks to Cody Appel for acquiring the guitar and original paperwork from James Gross’ wife Peggy.