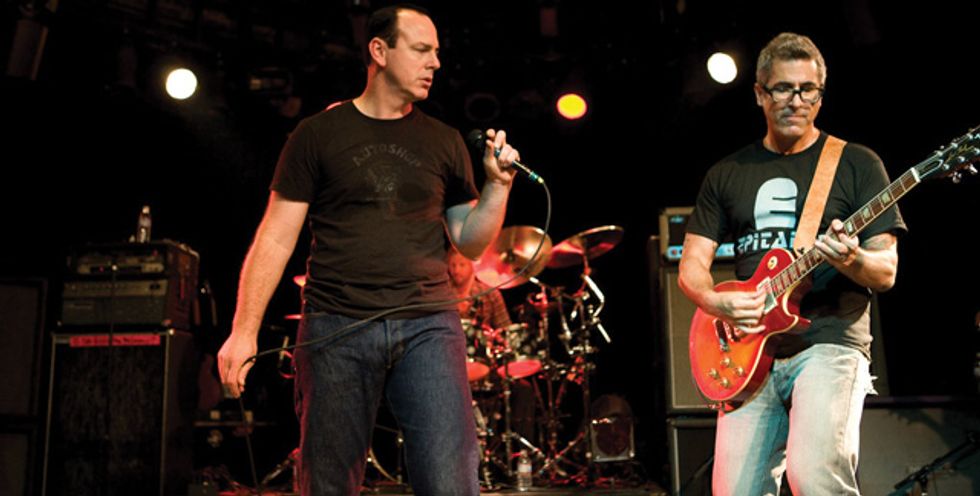

Brett Gurewitz plays with Bad

Religion at the Glass House in

Pomona, California, at the 2007

Warped Tour Pre-Party. Photo courtesy

of Epitaph Records

“it’s like a rebirth or recharge,” says Brett Gurewitz, cofounding guitarist of Bad Religion, about the band’s new True North. “We just wanted to challenge ourselves to make an album like we did years ago—to reconnect with our punk-rock roots.”

After various lineups and major-label releases, the melodic-hardcore vets have launched their 16th album, one that finds them more comfortable in their own skin— or at least the skin of their earliest years. In that sense, it’s the most Bad Religion-like record in nearly two decades. And Gurewitz says it was one of the easiest to write, too.

Formed in 1979 by Gurewitz, Greg Graffin (vocals), Jay Bentley (bass), and Jay Ziskrout (drummer), the L.A.-based foursome was influenced by SoCal forebears like the Germs and Black Flag, while Graffin’s academic-anarchist lyrics were inspired by heady writers like Carl Sagan and Noam Chomsky. In 1982, the band released its blistering debut, How Could Hell Be Any Worse?, on Epitaph Records, which Gurewitz founded and still operates.

The very next year, Bentley and Ziskrout departed, and the next BR album was the keyboard-heavy blunder Into the Unknown. The band went on hiatus after the album was panned by fans and critics. They reconvened in ’85 and tacitly admitted their misstep with Into the Known, which featured Circle Jerks guitarist Greg Hetson due to Gurewitz’s battle with substance abuse.

In 1986, Gurewitz and Bentley returned to the fold and the rekindled songwriting chemistry between Gurewitz and Graffin propelled the band into its prosperous prime. From ’88–’90, Bad Religion virtually redefined modern punk with three albums: the ’90s-punk archetype Suffer, the pummelingly melodic No Control, and the poignantly fiery Against the Grain. Each showcased the band’s new musical foundation— super-tight breakneck rhythms, three-part harmonies (what they like to call “oozin’ aahs”), and articulate, establishment challenging lyrics.

“One of the things Bad Religion contributed to punk rock was three-part melodies and detailed background vocals,” says Gurewitz. “It was just something I was really fond of—probably because I was a California kid who grew up on the Beach Boys—and felt it gave a musicality to our strong messages. We are a band after all [laughs].”

After two more solid releases, the band ran into major mayhem when they signed to a major label. Shortly after their Atlantic Records debut, Stranger Than Fiction, the company re-released Recipe for Hate—which had already been released by Epitaph. As it hit the streets, Gurewitz left to handle the soaring popularity of Epitaph artists the Offspring and Rancid. Many in the punk-rock community suggested Gurewitz disliked the big-label bounce, but his explanation is that, “Bad Religion was well on its way, and it was an important time at Epitaph, so I needed to be there to aid in the hectic day-to-day ventures.”

Hardcore veteran Brian Baker of Minor Threat filled in as the band’s second guitarist alongside Hetson, but lukewarm sales of the next three albums pushed Bad Religion back to the welcoming arms of Epitaph and Gurewitz, who rejoined and made the band a sextet in 2002.

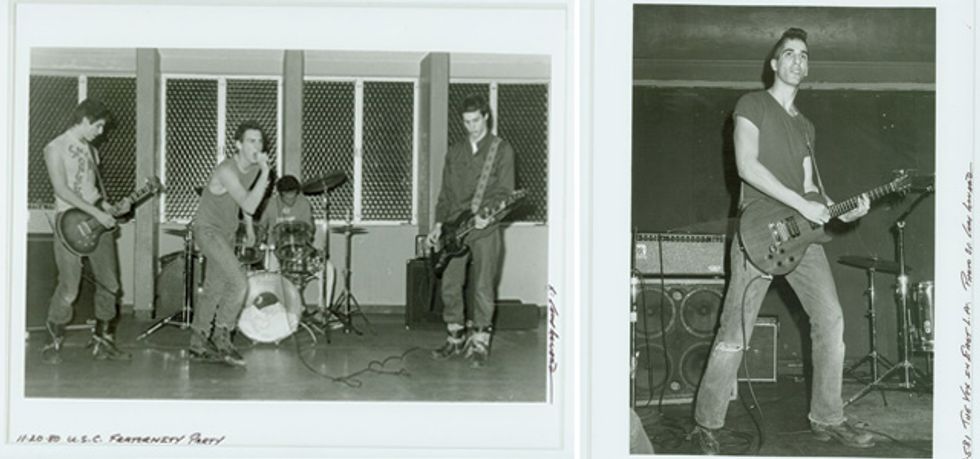

LEFT: Gurewitz (far left) at one of Bad Religion’s first shows—a University of Southern California frat

party held on November 20, 1980. Photo by Gary Leonard / Epitaph Records RIGHT: In this pic from a March 5, 1981, gig at the Vex Club in East L.A., Gurewitz proselytizes with a

Les Paul plugged into a Music Man head. Photo by Gary Leonard / Epitaph Records

His return alleviated some of the songwriting burden previously shouldered by Graffin, and it couldn't help but rekindle the signature sound.

“I am proud of every piece of music we’ve put out over the last 30+ years, but it was just time to make an album like this,” Gurewitz says of True North. “After setting out to limit ourselves to write fast, up-tempo songs around two minutes [long], this was the most fun, enthusiastic, and motivating project we’ve done in a long time.”

To get more details on the famous humanists' fearless and perennial holy war for peace and rationality through unimpeachable punk musicianship, we recently spoke with Gurewitz about the new guitar that inspired him while recording True North, and how record labels can still be relevant and beneficial to artists in 2013 and beyond.

While recording True North, Bad

Religion not only went back to its roots

with faster, shorter songs, but you went

back to recording on actual tape. Tell us

about the process of straddling the analog

and digital worlds this time around.

We tracked everything to tape and then

dumped it all into Pro Tools and mixed

the album digitally. We used the tape

machine as a bridge, but the interesting

thing about that is, unlike other things

you can put between yourself and the

ultimate recording medium, tape isn’t

a plug-in—it’s really a process. It’s a

way of working, because it’s very linear

as opposed to being random access.

Recording to tape is a more musical way

of thinking and communicating, and it's

also a more efficient way of working.

How did that affect the process of

recording the guitar parts?

Our goal for every song—which we

accomplished—was to record all the

instrumentation in one continuous

take before dumping it into Pro Tools.

We wouldn’t just cut a solid verse, fly

it into the computer, and then duplicate

it throughout the rest of the song

with crossfades. The songs on True

North don’t have any crossfades or edits

points. To me, that approach of splicing

and duplicating music—for our band

and any type of guitar-driven music

in general—sterilizes the art form.

Another positive that we really enjoy

with recording to tape is getting the

best noise-to-signal ratio, so it gives the

recording just a little bit of that old-school

tape compression.

You’ve produced a lot of Bad Religion’s

catalog, as well as other Epitaph bands

over the last 30 years. How does your

approach change with your own band?

Well, producing Bad Religion is definitely

my favorite thing to produce, because it

was the first thing I started working on way

back in ’81. Joe Barresi is part of the family

now, too—he’s worked on the last three

albums now—so it’s just become friends

hanging out, doing what we love. The new

ingredient or wrinkle this time was that I sat

in with him when he mixed True North. On

the two previous albums, I left the mixing to

Joe, but for this one I went in there and said

to him, "We’re looking for a particular old-school

sound. I mixed all those old records,

how about I take a shot at mixing this album

with you?" Joe typically works in the heavier

areas of rock, like Tool and the Jesus Lizard,

so with mixing True North we focused on not

overemphasizing or pushing anything too

much. When I work on Bad Religion, or anything

for that matter, my goal is to make seem

as realistic and true-to-form as possible. I want

you to feel like you're in the studio when you

hear it back through your iPod [laughs].

What are the main guitars you used on

True North?

All three of us tend to favor Gibson Les Pauls

because they fill the mix a lot better and typically

sound aggressive while still being articulate,

at least for what we do in Bad Religion.

I prefer guitars with shorter scale lengths

because they’re easier for me to play.

Another guitar we used quite a bit was a Nash Guitars Telecaster[-style]. I found it to be really punchy, and it lacked a lot of the shrill or brittleness that some Teles can have. We were happily surprised at how well it added to the Les Paul sounds.

Bad Religion cofounders Greg Graffin and Brett Gurewitz at the 2007 Warped Tour Pre-Party.

Photo courtesy of Epitaph Records

In the past, you've often bought a new guitar

leading into a new album cycle because

you view the instrument as a writing partner

and motivational tool. What new gear

purchases did you make this time?

My new toy this year was a tobacco-burst

Fender Kurt Cobain Signature Jaguar. It

has a very full, complete sound like a Les

Paul, but it also has these crazy, ringing

overtones that are caused by the bridge

being much more springy than a standard

bridge that’s entirely anchored to the body.

Those type of overtones are richly harmonic

and complemented the tones

from the Les Pauls.

One of the guitars you’ve had for a

long time is the red, sticker-covered

super-strat. What’s the story about

that guitar and did it see some time on

True North?

Oh yeah, I call that one "the Red

Rocker.” That’s a single-pickup Charvel

I bought in ’89 while on tour in Boston

because mine had gotten stolen the

night before. I went into the nearest

music store and bought it. Over the

years, I’ve just swapped things off it

out of necessity. The neck now is an

unfinished ESP maple neck with a

maple fretboard that has jumbo frets

because the old neck played like crap.

It went out of tune a lot, so I replaced

the stock tuners with some high-quality

Schaller tuning machines. I had the

tone knob circuitry disconnected, so the

signal path is even more direct from the

pickup to the amp—I normally leave

tone knobs wide open, so it just made

sense on this one-pickup monster. And,

I also put in a Seymour Duncan JB in

the bridge position, which all my Les

Pauls have, too. Everything I’ve done

to it ended up making it sound like a

brighter Les Paul.

The Red Rocker gets on every album. It wasn’t featured that much this time around, but it’s been with me for over 20 years, so it’s paid its dues and deserves some studio time [laughs].

What do you like so much about the

Duncan JB versus other humbuckers?

I prefer the JB because of the smooth

midrange within the overdriven Marshall

sound I like, particularly in the low

mids around the 500–600 Hz range.

Sometimes other humbuckers—especially

newer ones—have such high outputs that

you can’t hear the gain stages of the amp

as much.

What amplifiers did you record with?

We pretty much exclusively used the

Marshall JCM800. Aside from the new

guitars, we deliberately tried to keep

most of the gear simplistic and reminiscent

to our early days, so we just stuck

with what we know when it came to

amps. We also worked with an older

’70s Marshall JMP, and both heads ran

through a Mesa/Boogie 4x12 that has

Celestion Vintage 30s.

Why do you prefer Mesa cabs with the

Marshall heads?

They have a bigger box that creates a lot

more low-end presence and oomph.

In recent shows from the 30th-anniversary

tour, you used a Diezel VH4

head. Did that or any other amps make

appearances on True North?

I still have the VH4, but I just don’t

really like it that much. I know Adam

Jones from Tool gets some really

dynamic and thick sounds for what

they do, but every time I’ve tried it,

it just sounds fizzy. It does give you

infinite sustain, but I just can’t get the

Marshall’s warm, creamy punch out of

it. The EVH 5150 III is an amp that I

really like and have been using live—as

well as on most of the tracks for The

Dissent of Man—but I didn’t really use

it much on True North.

Gurewitz works the mixing console while co-producing True North at producer Joe Barresi’s House of Compression. Photo courtesy of Epitaph Records

Besides the subtle phaser on the opening

of “The Past Is Dead,” did you

use any effects this time around?

No, not really at all—True North was

definitely a less-is-more record. The

only effects we used besides that small

phaser part were delay and reverb on the

background vocals.

When you're working in the studio,

is there anything you absolutely need

to have in terms of microphones, mic

preamps, or other gear?

I always use a Shure SM57 for guitars,

and I put it right on the speaker,

pointed right at the [cone-paper's]

crease because I feel it gives a little more

woof that way. I always experiment, and

if I need something to ring out a little

more, I’ll go off axis but still point it at

the cone. I’ll also use another large-diaphragm

condenser mic, like a Neumann

U87, on another speaker of the same

cabinet. I’ll take my time to dial-in the

exact distances the mics are placed so

the phase coherence is as perfect as possible.

But the majority of the guitars

you hear on Bad Religion records come

from the SM57. I just use a tiny bit of

the condenser mic to add a little more well-rounded

body to the sound. I exclusively

use Neve channel strips when tracking guitars,

because you can’t find a better or more

dynamic preamp or EQ.

My favorite mic preamp on vocals is the Martech MSS-10—it’s an old-school, solid-state, 1-channel pre with a high-quality VU meter. I’ve never found anything to beat it, in terms of realistic vocal reproduction, in recording. I’m not a big fan of the new fad of tube mics that are trying to be retro—they have too much built-in gain for me. I’d rather use a lower-gain mic matched with the Martech to get vocals peaking near distortion—that’s what those old records and real rock ’n’ roll sound like to me. And I always use my original Focusrite Red 3 compressor with the detented pots—nothing beats it.

What's your favorite song off of True

North and why?

I’d have to actually say the title track,

because it’s classic Bad Religion—straight-ahead

punk-rock guitars, beautiful vocal

harmonies, and thought-provoking lyrics

that offer an uplifting message.

“Hello Cruel World” is almost four minutes

long and has a more subdued pace similar

to “Sanity” off No Control and “Digital

Boy” from Against the Grain. How did

that come about, given that you guys were

focused on a more up-tempo and retro writing

strategy?

Even our fastest, most punk-rock albums

have always had a slower, longer song—like

“Drastic Actions” off our first EP, Bad

Religion. We were influenced by the Germs’

song called “Shut Down (Annihilation

Man),” which is super, super slow. But

other than that, all their songs were hyper-fast.

We always looked up to them, so we

took a page out of their book and have

been doing it ever since. I don’t think it’d

be a true Bad Religion album without a

slower song that broke up the pace. So even

though we broke our own rule [of having

all short songs on the album]… we kind of

still followed one of our other ideals.

“Dharma and the Bomb” has some great

verse riffage that sounds like a psychobilly

song from Deadbolt or the Misfits'

“Hollywood Babylon,” while the call-and-response "oh yeah” vocals in the

chorus sounds like old SoCal surf rock.

What was the inspiration for that song?

That was my attempt at writing a surf-punk

song [laughs] … it almost didn’t make the

record. Before meeting for pre-production, I

double-checked the song files on my home

computer. I clicked on the song—which

was half finished and didn't have any

words because I didn’t think it was going

anywhere—but when I heard it playback I

thought, “God, that sounds pretty good.” So

I decided to bring that one along, just in case.

Even though it wasn’t entirely finished, I had

the guys track it. I finished the lyrics and the

melody in the studio and, for whatever reason,

Greg was having a tough time singing it

so I did a placeholder vocal to show him how

the lyrics should sound over top the music.

But he could never get it right.

So that’s you singing lead, not Greg?

Yes, that was actually me singing all the

main parts. Greg helped out with the background

harmonies. I really like this song,

too—not just because I’m singing leads,

but because it almost didn’t end up on the

album and I don’t hate my voice [laughs]. I

normally hate my voice when it’s front and

center, but not so much with “Dharma.”

Left to right: Brooks Wackerman (drums), Gurewitz, Graffin, Jay Bentley (bass), and Brian Baker (guitars) at producer Joe Barresi’s House of Compression

studio on July 23, 2012. Photo courtesy of Epitaph Records

You're the head of one of the largest independent

record labels today. What's your

take on how labels and the music industry

need to evolve to support artists?

I’d suggest providing state-of-the-art,

cutting-edge, music-marketing strategies

in digital mp3s, physical music, and direct

artist-to-fan connections and relationships.

That’s how labels can still be useful and

relevant in the current music landscape.

There’s no doubt some artists can do it all

themselves—Epitaph got started because I

was an artist who could do it myself—but

not all artists are that into marketing and

distribution. They would rather focus on

lyrics, music, and performing live. So that’s

where they have to make a smart decision

and find a label that will work for them

instead of them working for the label. I’m

a firm believer that anyone who gets to the

top has a team behind them.

Brett Gurewitz's Gear

Guitars

Gibson Les Paul

Fender Kurt Cobain Signature Jaguar

Nash Guitars T-style

Late-’80s Charvel with a maple ESP neck,

Seymour Duncan JB pickup,

and a Badass bridge

Amps

Mid-’80s Marshall JCM800 head

’70s Marshall JMP head

Mesa Boogie 4x12 cabinet loaded

with Celestion Vintage 30s

Effects

None

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

Ernie Ball or Jim Dunlop .010–.046

Jim Dunlop Tortex .60 mm picks

Speaking of self-marketing, have you or

anyone in the band ever regretted the

name "Bad Religion" or the infamous

"crossbuster" logo?

No, I don’t think so. When we first started

out I might’ve regretted it, because it

caused us some hardship with promoters,

venues, and people with conflicting points

of view. But now I feel it’s been a really

powerful force for positive change. What

I’ve come to believe is that social norms

aren’t generally changed through lecturing

and scholarship. Art, literature, comedians,

and musicians can have a more profound

effect on change than cultural zeitgeists or

pontificators like Richard Dawkins. You

have 30 years of kids wearing crossbuster

shirts to school and then going on to lead

successful lives as professionals, parents, and

citizens. You get some vindication showing

that the band and its fans aren’t as bad,

misguided, or damned as they originally

believed [laughs].

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)