Hi, and welcome to my new instructional column. It's inspired by the most common complaint I hear from intermediate and advanced players: “I feel like I play the same things every time I pick up a guitar." This series is about getting unstuck.

Guitar isn't like most other instruments. It's possible to play for just a couple of weeks and make something that sounds fairly musical. Compare that to, say, most orchestral instruments, where simply producing a listenable tone can take years. But there's a downside to guitar's accessibility: Many of us learn to play using the same licks, patterns, and formulas. When muscle memory takes over, you can find yourself trapped in a box like a mediocre mime. Our job here is smashing boxes.

Are Rules for Tools?

Some dopey guitar teachers insist there's a single “correct" way to play. Nonsense! The history of our instrument proves the opposite. Consider Django, Charlie, Rosetta, Wes, Jimi, and Eddie, and beyond. Our greatest players are often the boldest rule-breakers.

But there's more to this column than switching off your conscious mind and going apeshit on the fretboard. (Though that's often a great idea.) We're not going to ignore the “rules" so much as question them. We'll turn them backwards, upside down, and inside out. Warning: Some of this will be technically and conceptually challenging.

Where You're Coming From

This column is aimed at intermediate and advanced players. It will probably appeal most to restless, inquisitive guitarists eager to develop their own personal style, as opposed to those whose goal is to imitate their heroes as accurately as possible. (Not that there's anything wrong with that.) Music reading skills aren't required—all examples will appear in both standard notation and tab. It doesn't matter much which styles you usually play. We'll steal ideas from everywhere, and most of the skills we'll discuss are applicable to all genres. If there's a motto here, it's “Originality beats regurgitation." Or maybe, in the words of Sonic Youth, “Kill Yr Idols."

Where I'm Coming From

A few words about my background and biases to help you decide whether I'm worth listening to: I've played for over 45 years. I've taught professionally since age 13. I started out as a typical rock folk player, but then studied jazz guitar with the great Ted Greene from age 17. I have degrees in classical music composition from UCLA (BA) and UC Berkeley (MA). An obsession with African music and post-punk made me drop out of a PhD program to play funky/noisy shit in various bands. I've been a guitar magazine editor on and off for 30 years. I've recorded and performed with Tom Waits, PJ Harvey, Tracy Chapman, Flea, Les Claypool, DJ Shadow, John Cale, and many other artists. My favorite musicians are Claude Debussy, Duke Ellington, and Claudio Monteverdi, none of whom played guitar.

Still with me? Let's go.

The CAGED System—and When to Forget It

A frequent subject here will be playing by ear rather than by eye. That's harder than it sounds! Most of us learned the fretboard via the same pentatonic and diatonic fingering patterns, with the understanding that as long as we stayed in the box, every note would sound acceptable. That's not a bad way to learn, but too often it limits our ears and imaginations. It can be like painting by numbers, as opposed to just painting.

I'm not saying we should forget those formulas. In fact, I highly recommend learning the CAGED system. If you're not familiar with that method of visualizing the fretboard in terms of simple open-position chords shapes, you can consider it homework in advance of upcoming lessons. This Premier Guitar article by Mike Cramer offers a nice, clear introduction. Cramer takes the concepts further in The CAGED System Demystified, an inexpensive e-book available from the PG store.

But for the moment, forget that stuff even exists.

One-String Wonders

The first time you picked up a guitar, you might have plucked out a melody on a single string. Later, you learned to play across the strings. It's so much more efficient that way! No need to lurch halfway up the fretboard when you can just slide over to an adjacent string.

But for now, let's return to those single-string roots. We're going to pick out tunes on a single string, shifting positions as needed. There are big benefits to practicing this way:

- It liberates you from muscle-memory box patterns.

- You'll get better at playing the melodies you hear in your head.

- You'll be able to shift positions with greater speed and accuracy.

- When you play this way, you become more like a vocalist or wind player. This can steer you away from boring guitar clichés.

- When you doplay in familiar “box" positions, you'll be confident enough to step outside them.

I'm not just talking about long-term benefits here. If you practice this technique for just a week or so, I pretty much guarantee you'll play with noticeably more confidence and creativity.

Play Like You're Singing

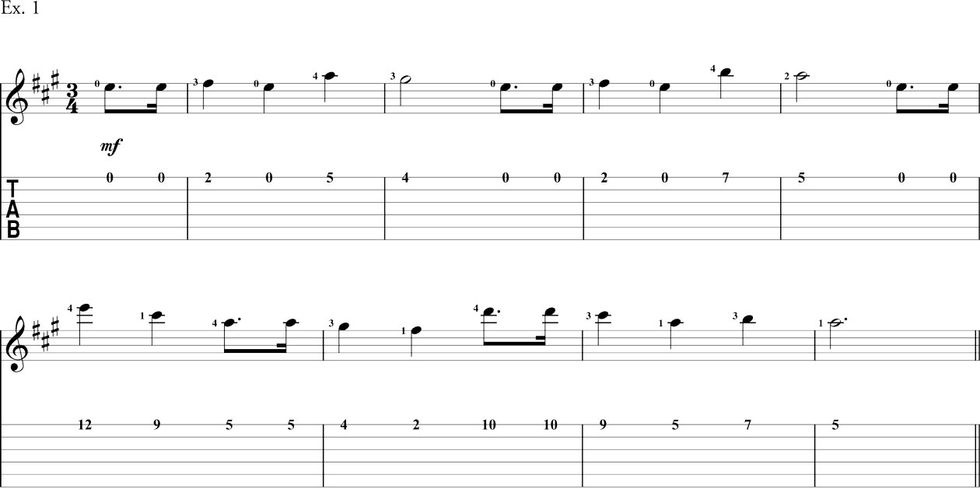

Let's start with a familiar melody: “Happy Birthday to You." Starting on the open 1st string, try picking out the melody by ear. (Try not to read from Ex. 1 unless you need to.)

Once you've located the notes, try playing it as legato as possible. (Legato means letting each note ring until the instant you finger the next note. It's the opposite of staccato, which means making each note short, with a moment of silence between each one.)

Now try it in another key, starting on the 1st fret of the 2nd string. It's harder to get consistent legato phrasing in this position because there are no open strings to ring out while you shift positions.

Sure, the first four notes are easy. And if you have large and/or flexible hands, you might be able to reach the 6th-fret note at the end of the first measure without shifting out of position. But you'll definitely need to shift position to hit the 8th-fret note at the end of measure 3. It gets even hairier between measures 3 and 4, where you must leap from the 1st fret to the 13th.

It's not terribly hard to hit the notes, but can you play them like a singer? Hum the tune to yourself. There's probably no gap at all between the first six notes, though chances are you'll pause for a breath before the next phrase. Can you play it that smoothly? Forget about speed—playing slowly is great practice.

Fingers in Motion

A technique I learned from my first classical teacher may help here. She advised me to start moving my fingers while the last note before a position shift is still ringing out. In Image 1, I'm fretting the 1st-string note, but my other fingers are already on their way to a higher position. Try this in the spots where you must leap from the 1st fret to the 6th, 8th, and 13th frets.

Image 1

Use the reverse technique when leaping from a higher fret to a lower one. In Image 2, I'm sustaining the 13th-fret note while other fingers depart toward lower frets.

Image 2

Try doing the same with whatever melody pops into your head. “Silent Night," “Star-Spangled Banner," the Star Warstheme, “Shake It Off"—it doesn't matter. Choose a random string and fret. Find the notes. And then figure out how to play them as legato as possible. If the melody exceeds the range of a single string, just move to the next one. I won't report you to the single-string police.

If you're feeling brave, try this with your eyes closed. (Brace for humbling mistakes.) If you can play most tunes by ear on a single string with your eyes closed … you're really good. Do you give lessons? (Asking for a friend.)

Bach Around the Clock

Let's conclude with a truly great melody from J.S. Bach's Orchestral Suite #3 in D Major. About 150 years after Bach's 1750 death, a violinist named August Wilhelmj arranged one of the movements for solo violin and accompaniment. He decided to play the entire melody on the violin's 4th string, earning the piece the nickname “Air on a G String." (Insert underwear joke here.)

Wilhelmj probably didn't make that choice just so he could say, “Check my chops, bitches!" Playing it that way makes it feel like a vocal piece, for the reasons mentioned above. (When a classical instrumental piece is named “Air," “Aria," or “Arie," it usually means it's written to sound like a vocal piece, often an operatic aria.)

The violin's G string is in the same octave as the guitar's G string, so we can do the same trick. I recorded it on electric guitar, plus electric bass and second guitar. Even if you're not a classical music geek, the piece might sound familiar. Procol Harum swiped the bass line and harmonic progression for their 1967 hit “A Whiter Shade of Pale." However, the violin melody doesn't appear in that song. Check it out in Ex. 3.

Click here for Ex. 3

Don't be intimidated by all the notes in measure 2. The tempo is very slow, so they're not all that fast. (If you still have trouble with the trill, check out the alternative measure 2 in the appendix below.) The hardest part is playing the melody legato despite the position shifts. It's also tricky sustaining the long notes. (It's easy on violin, where the bow keeps the energy going.)

So you can check out the accompaniment, Ex. 4 shows the electric bass and second guitar parts.

Click here for Ex. 4

Practice one-string exercises for a while, and then try some conventional playing. Does anything feel different after the first day? After a week? I'm eager to hear about your experiences, so please post them to comments.

Thanks for joining me. Many more daring adventures to come!

Appendix (For Classical Geeks Only)

This is only the first half of the piece. Ex. 5) hereDownload a public domain score for the entire suite ( . (The “Air" movement starts on page 232.) You'll find performances of the piece featuring many different instruments on YouTube.

You may notice that the second measure in Ex. 3 is very different from the one in the score, which looks like Ex. 6.

Like much 18th-century music, this piece includes ornamentation, depicted by the grace notes and trill symbol. I wrote these out as individual notes in Ex. 3 for two reasons.

First, music notation software isn't good at depicting ornamentation in tablature. By writing out everything as it's actually played, tab readers can perform this accurately.

Also, these symbols were interpreted differently in Bach's day than they are today. Some performances strive to play these with as much historical accuracy as possible. Other recordings (especially older ones) feature the ornaments in a non-Baroque style.

In modern practice, a trill means oscillating quickly between the note under the trill sign and the next scale step above it. That means starting this trill on C#. But a Baroque musician would have started on the note abovethe one shown (D, in this case).

Also, a modern performer usually interprets a grace note (the mini-sized notes, shown as smaller numerals in the tab) by playing it very quickly an instant before the beat. A Baroque musician would have played it directly on the beat, and not necessarily quickly. Usually, the grace note gets half the duration of the note it proceeds. So that last grace note in measure 2 would probably have been played as a leisurely eighth-note.

There's nothing wrong with substituting the simplified measure 2 in Ex. 6. It'll still sound beautiful.