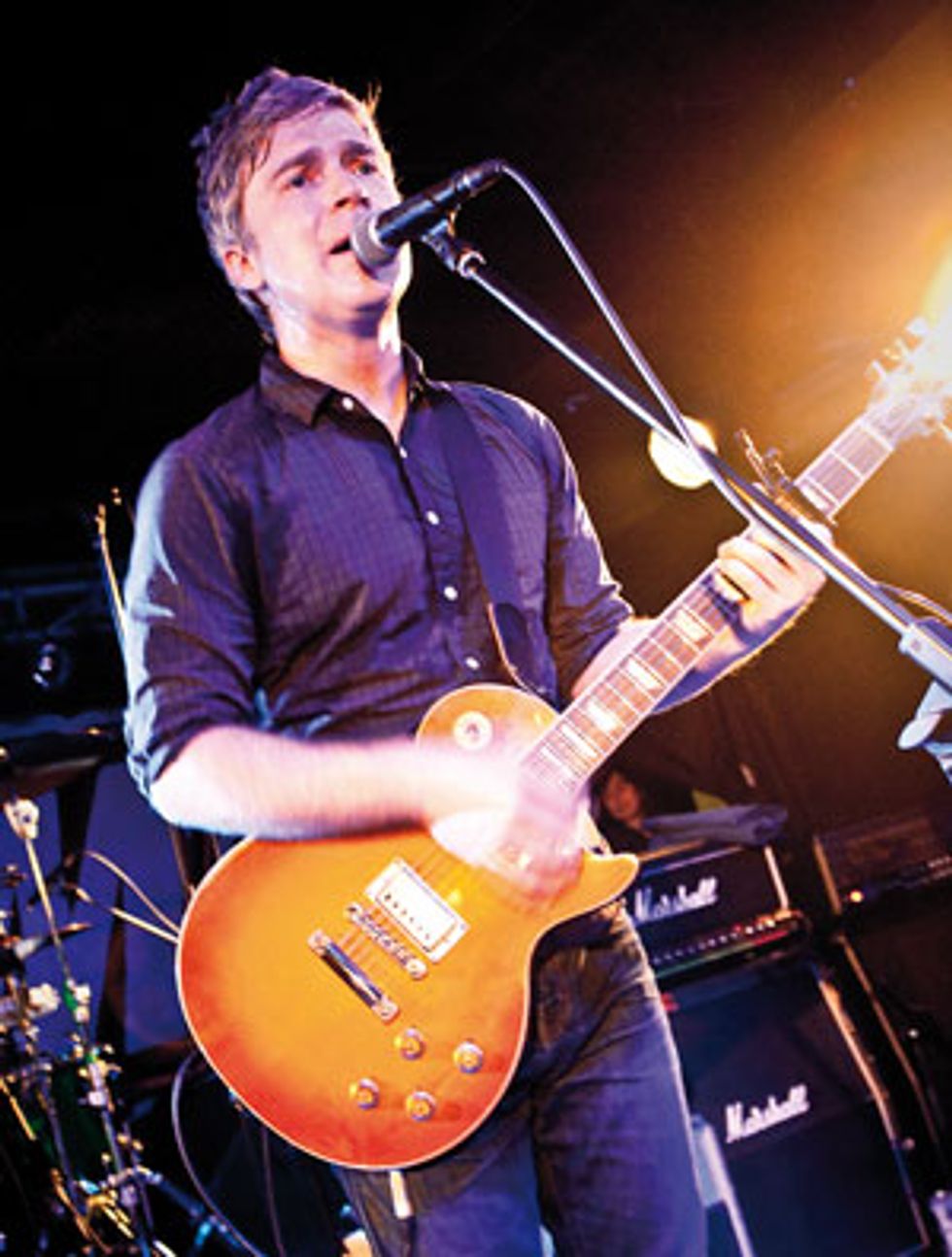

Matthew Caws plays his trademark Les Paul at a concert in Italy on February

23, 2012. Photo by Marina Ravizza

Though Nada Surf’s first hit was the Weezer-esque “Popular” (from their 1996 debut album, High/Low, which was produced by the Cars’ Ric Ocasek), the irony for New York-based trio of Matthew Caws (vocals and guitars), Daniel Lorca (bass/vocals), and Ira Elliot (drums/vocals)—who are still going strong 16 years later—is that it has also been their biggest to date. “Popular” reached No. 11 on Billboard’s Modern Rock charts, but the band never quite achieved big mainstream success with its follow-up efforts. But when you consider the tune’s sardonic tear down of the whole concept of coolness, that failure to ignite big-time might not seem like such a surprise after all. But it gets even more ironic.

When it came time for the threesome to record their 1998 sophomore effort, The Proximity Effect, Elektra Records didn’t think it was commercial enough and told them to record a few cover songs and/or an acoustic version of “Popular” to release as singles. In the spirit of their breakthrough song, Caws and company declined—they felt the album was just fine as-is. Elektra responded by dropping the band after the album’s European release—right in the middle of the subsequent tour.

One gets the feeling the label still regrets that decision, though, because Nada Surf came into its own during that period: Though fickle fate hasn’t since struck with the same fortuitous (and financially rewarding) timing that it did with “Popular,” Caws, Lorca, and Elliot have since perfected their power-pop hooks, delectable multi-harmony background vocals, and dynamic guitar layering approach in a way that could’ve been exploited to great effect by a major label.

And with this year’s super-energetic The Stars Are Indifferent to Astronomy, Nada Surf proves the intervening years have only made their infectious songwriting more potent. Chock-full of radio-ready choruses augmented with cranked, harmonically rich power chords and crystalline acoustic textures, Astronomy builds on Surf’s successful approach by bringing in former Guided by Voices guitarist Doug Gillard to act as a creative foil to Caws’ ’68 Les Paul-powered foundations.

In our recent interview, Caws proved anything but indifferent to his craft, going into great detail about his love for his Marshall JCM800 and his collection of low-powered vintage amps, as well as his painstaking songwriting process and his meticulous methods for laying down bracing, multitextured guitar tracks in the studio.

The new album is a tour de

force of guitar layering. In a

song like “Clear Eye Clouded

Mind,” which part came

first—the quarter-note power

chord foundation or the more

urgent-sounding eighth-note

riffs that complement it?

Doug [Gillard] plays the eighthnote

riffs, but we tracked the

songs completely until he came in

and did extra little bits and bobs.

The big blocks come first, unless

it’s something like the beginning

of “Waiting for Something”—

which is its own little piece of

music. I tend to write from the

bottom up: Y’know, acoustic guitar

and C, D, G type of stuff.

So you tend to get the chord

progression and then add melodies

and harmonies to it?

Exactly. Well, I get the chord

progression and the sung melody

at the same time. For years,

I’ve recorded little bits and

progressions, etc., onto tape and

I’ve scribbled in a zillion notebooks,

but most of that stuff

just disappears. What tends to

stick are the songs where the

chords and vocal melody come

to me at the same time.

So you still use tape, despite

all the modern conveniences,

like smartphones?

Yeah, I just sit down with a

Panasonic or Radio Shack tape

recorder—even though I’ve

had 8-tracks and 4-tracks and

Logic and GarageBand and

everything. I like cassette players

because they’re so instant

and you don’t have to look at

a screen. And it’s also so unintimidating—

because you know

you’re not doing anything permanent,

so you feel kind of free.

I usually write a third or half of a song, and once I get something I like, instead of finishing, I generally, like, get hungry and want a sandwich [laughs]. And then I fill up these tapes with that stuff, and every couple of years I force myself to sit down and listen through these—it’s like pulling teeth. It’s 98 percent forgettable—or painfully mediocre—but it’s worth it for that two percent of stuff that actually turns into something that we use on a record.

How do you know which ones

are the two-percent keepers?

Well, because I’m not cringing,

first of all [laughs]. That’s the

first indicator. It’s, like, “Oh my

god, I’m not in pain—wait a

minute! I’m not hiding under

my own desk!”

Why would you be cringing

and in pain?

I don’t know how other people

do it, but I have to feel free to

just say anything or sing anything

or try anything. And that’s

why I can’t write with other

people nearby, even if we’re on

the road and have separate hotel

rooms—which is definitely not

all the time, because we’re not

on that kind of a budget. But

even if we have separate rooms,

if somebody I know is in the

next room, I can’t do anything.

It’s such a private thing. Here’s

the other thing: If I’m working

on something and I wake up

the next morning and it’s not in

my head, that’s a bad sign. But

if the first thing I think of when

I wake up in the morning is the

hook I was working on the night

before, then it gives me hope

and I work harder on it.

Engineer Chris Shaw on the Stars Sessions

Regarding the guitar-tracking portions of Nada Surf’s new The Stars Are Indifferent to Astronomy—which was recorded over the course of five days at Headgear in Brooklyn, New York—producer/engineer Chris Shaw says, “In general, it was easy because Matthew used THD Hot Plates to keep his volume at a reasonable level. And recording Doug was incredible, as he brought really well-thought-out parts to each song. The guy’s a monster.” To capture the remarkably textured and nuanced electric tones, Shaw used a Shure SM57 and an AKG 414. “I placed them around two-and-a-half to three inches from the cabinet, pointing straight ahead at the area halfway between the outside edge and the center of the speaker. To change things up when we were double tracking, I would move the mics closer or further back.” For the sparkling acoustic parts, including the Gibson J-200 doubled with a Nashville-tuned Guild jumbo on “When I Was Young,” Shaw employed an AKG 414 and a DPA/B&K 4011. “The 414 was pointed at the lower half of the bridge, at a 45-degree angle, while the 4011 was directed at the point where the neck joins the body and angled slightly toward the soundhole.” Both mics were six to nine inches away from the instrument. All mics were routed through a pair of Daking 52270 mic preamps/EQs and a pair of Empirical Labs Distressors for compression.

Is that usually the lyrical hook

or the melody—or both?

Both. It’s singing the hook and

thinking the chords. But even

if it’s just a little guitar hook

or a harmony—if I feel a little

haunted by it for a couple of

days, then I’m on to something.

Before a record gets done, I’ve

probably sung in my head or listened

to those little pieces a hundred

times each—because I just

do it and do it and do it until I

get sick of it, and then I throw

it away. But if I listen again and

again and again, and I don’t get

sick of it, then I think that might

be something that’s going to last.

Is the cringe-inducing stuff

usually the words you’ve

laid down, the whole thing

together, or either one of

those two?

Oh, it’s the words. A chord

progression will never make me

cringe, it’ll just make me yawn.

It can only be boring—it can’t

be, like … stupid. But it only

takes a couple of choice words

to make it stupid [laughs].

Has your process of writing

changed over the years?

It’s been pretty constant. But

when we did the release party

for [2010’s covers album] If I

Had a Hi-Fi, we prepared for

it by playing all of [2002’s]

Let Go in one club one night,

all of [2005’s] The Weight Is a

Gift another night, and all of

[2008’s] Lucky the next night in

another club. So, to brush up

on those songs, I had to listen to

those three records a lot, and it

really struck me that those versions

sounded so different from

how we ended up playing them

onstage—and also different from

the way I remembered writing

them and playing them in early

practices. I found that we’d sort

of grown into two bands—one

that’d kept the same energy

onstage over the years, and one

that had started to kind of slow

down in the studio.

At first I was really frustrated, thinking that we’d gone into some kind of groupthink. Like, “Okay, we’re older now, and this is our career, and we’re trying to make stuff that’s going to last. Slow down! Calm down now! Hold on a minute—don’t run away with it, you kids!” But then when we recorded Hi-Fi, it was so much fun and there was so much good energy coming from the drums, for example—Ira [Elliot] is an incredible live drummer— and I realized that it was actually all my fault. It was because I was finishing songs in the studio for years—not on purpose, but just because I’m an idiot and couldn’t finish them on time. I realized we play so differently when we really know the stuff and we’re not tracking while also thinking, “Hmm … should the chorus be two times or three times? Let’s try this one more time, but do the chorus twice.” That kind of thinking on the fly was keeping us from sounding like we do live—where we just kind of go for it. So I made a concerted effort this time to just write 10 songs, instead of working on 25 half-done ideas. I got a big kitchen table, spread out 10 pieces of paper, and just tried to finish.

Nada Surf frontman Matthew Caws rocks his Black Beauty in Mezzago, near Milan, Italy, last February.

Photo by Marina Ravizza

Well, it worked—the songs

are tight and they rock like

you guys have been playing

them for a while.

Exactly, and we haven’t had that

luxury in ages. We made our first

album [1996’s High/Low] twice.

We made it with a different

drummer with our pocket money

for a tiny label in Spain, and then

they ended up wanting to market

us to the rest of the world but we

were, like, “But you guys don’t

have anything going on outside

of Spain. We can’t give it to

you—sorry!” So when we made

it with Ric Ocasek, it was the

second time, so we knew those

songs cold. That was the only

other record we’ve made so fast.

This one we made in five days

of basic tracking. And, this time

we didn’t go out of town to get

away from home distractions, as

we’ve done for years. When we’ve

done that, you have that period

of closing up shop, packing up

your apartment, shipping some

gear, arriving in Seattle or San

Francisco, and then taking a day

off to recover from jet lag. When

you finally get back in the studio,

you’re, like, “Wait—how did that

[groove] feel again?” This time,

we finished the last practice on

a Sunday, rolled the gear three

blocks away to the nearest decent

studio, and the next day at noon

we were tracking. We didn’t have

to check a metronome, we didn’t

have to ask any questions—we

just did it. And it came out just

like it sounded in the practice

studio—which is exciting,

because now I don’t have to

listen to it through some filter,

like, “Yeah, well, y’know—it’s

an album. It’s a little different,

but that’s cool. How mature.”

This time, I hear it and I’m, like,

“Whoa—that’s us. Cool!”

The bass is locked in so tight

with the guitar on pretty

much all the songs. Do you

work extra hard with Daniel

to get a tight groove that really

maximizes that punchiness,

or is that lockstep power just

a result of how long you guys

have played together?

That’s just us playing together

for so long that, when we kind

of go into your basic, eighthnote

chugga-chugga thing, we’re

pretty locked—just because

that’s what we’ve been doing

for so long.

Did you track everything live

in the same room, with amps

in isolation rooms?

Yep, it was the three of us—me,

Daniel, and Ira. Doug [Gillard]

came in just for overdubs. My

guitar was going into two tweed

Deluxe replicas that my friend

J.J. built for me. He collects

new-old-stock parts [NOS], and

he made me a couple of tweed

Deluxe clones that have new

parts for everything that could

break down, and everything

that won’t break down is old.

Are those your go-to amps

now, or were those just what

you happened to use this time?

My go-to amp is a ’65 Fender

Deluxe Reverb reissue with a

Jensen Special Design speaker.

The Jensen speaker is important,

because the speaker the Deluxe

comes with is pretty brittle. I

usually use a THD Hot Plate,

too, to tame it down so I can

really listen to what it sounds like

without it hurting—because I

do like a pretty hyped-up Fender

sound. With an AC30 it’s impossible

to get the right tone without

blowing everybody off the

stage—you really have to crank

it. My go-to heavy sound is from

a Marshall JCM800 50-watt

head that I’ve had for years. Live,

I always run two Fender-type

amps—or Vox-type or Orange or

Silvertone—flanking a JCM800.

On this last tour in Europe, I

had an AC30 on one side and a

Deluxe Reverb on the other. The

two on the outside are always on,

and then the Marshall I turn on

and off the same way you would

a fuzz box. For years I tried channel

switching, but I got frustrated

with it, because in recording you

don’t do that—you get to the

chorus and you just add stuff

instead of taking it away. To

do that, I use a Morley George

Lynch Tripler pedal.

Do you have a go-to setup for

your jangly rhythm parts, and

if so, what are your preferred

pickup selections and amp

and effect settings?

The Deluxe Reverbs and tweed

clones are my go-to amps for

jangly parts. And I really only

have two main guitars in the

studio: One is a ’68 Les Paul

Custom Black Beauty, and then

I have a ’69 Tele that’s really

light. I tend to always be on

the bridge pickup—I’d rather

have the guitar always sound

bright, and then just dial the

treble back on the amp. The

only other variables are how

much gain to use on the amp

or whether to turn off the Hot

Plate and turn the amp down

a bit to get some sparkle, or to

bring the Hot Plate into it to

get some muscle. Live, though,

the amps tend to be pretty

cranked. I really like AC30s,

but I think the Deluxe is really

my favorite, because it does its

own kind of gain thing: You can

find a sweet spot where, if you

play lightly it’s crystal clear, but

if you dig in it’s crunched up.

That’s the best, because then it’s

just a question of your hands

deciding what you want to hear.

Caws’ Tweed Deluxe Clones

Nada Surf frontman Matthew Caws’ main amps for The Stars Are Indifferent to Astronomy were two tweed Fender Deluxe clones built by John “J.J.” Jenkins from TwangMaster Guitars (twangmasterguitars.com). “When I found Matthew was using THD Hot Plates to step down the wattage on his amplifiers, I asked him, ‘Why don’t you use amps that already have the wattage that you’re stepping your amps down to?’” Jenkins says. “Then I fired up the tweed Deluxe [clones] I built for myself, which run at about 15 watts or so, and I think he was an instant convert!”

To give Caws the tones he wanted in roadworthy amps, Jenkins says, “I wanted to build him a rig that preserves the vintage character of Leo Fender’s original 5E3 circuit, but that also enabled him to get parts and service anywhere his tours may take him. I started with a couple of fiberboard kits from Weber and a chassis from Mojotone. The transformers are Mercury Magnetics ToneClones—my go-to transformers. For the tone capacitors, I went with Jupiter paper-and-oils. They have a nice vintage sparkle and clarity, nicer than [Sprague] Orange Drops. The resistors are all carbon-comp, either Ohmite or NOS Allen-Bradleys. For tubes, I went with NOS RCA 5Y3 rectifiers, since there are plenty of them out there. The power tubes are new Tung-Sol 6V6s. They are the closest sounding to old RCA “black plates”—which are getting really hard to find at a good price. The 12AX7 preamp tube is also a Tung-Sol, and the 12AY7 is a gold-pin Electro-Harmonix. I used this tube compliment because they’re all still made or easily found in music or electronics stores worldwide. Another beauty of the 5E3 tweed Deluxe is that it doesn’t need tube biasing—you can just swap out the tubes and it will run fine. For speakers, I went with a 30-watt Weber 12A125A and a 25-watt Jensen P12R. The higher-wattage speakers give the amp a cleaner breakup, with more tube color and saturation than muddy speaker breakup, giving the amps a nice twang.”

Are the Les Paul and Tele

all-original?

Yep, I only changed the tuners

on the Les Paul—I put some

Waverlys on there. But of course

I kept the originals. I got both

of those at Main Drag Music in

Brooklyn about 15 years ago.

Are those the same guitars you

take on the road?

I only take Les Pauls on the

road. I have a 1960 Les Paul reissue

from 1996, and I also have

an Edwards, which is an incredible

Japanese knock-off made

by ESP. They can’t export them

here—they call them lawsuit

guitars because they’re so perfect.

They cost about a grand, they’re

light as a feather, and they sound

incredible. I actually may have

played that more than my Black

Beauty on this record.

Why do you only play Les

Pauls on the road?

For years, I was the only guitar

player, so I got completely

hooked on the thickness of the

sound. Even now, with Doug

playing with us on the road, I’m

still hooked—it’s what I know.

“Waiting for Something”

begins with a beautiful arpeggiated

part that’s doubled on

acoustic and an electric that’s

barely breaking up. When the

song kicks in, the driving, jangly

electrics lean a little to the

left side of the stereo field, and

you punctuate things occasionally

with drier, more straightahead

rock chords and riffs on

the right side—and then when

that muscular solo comes in

the middle of the stereo field, it

hits you right in the face. What

drives your decisions on stuff

like that—and do you make

panning decisions like that in

the studio during mixdown, or

do you actually envision parts

that way when you’re writing?

We do little mixdowns as we go.

I’m a big believer in really checking

out rough mixes and making

sure you don’t have to add too

much to it [at final mixdown]. I

do tend to want to double and

triple guitars all the time, and

Chris Shaw—Astronomy’s great,

great producer—did sort of hold

me back now and again.

“When I Was Young” has a

gorgeous acoustic 12-string

sound, with the bass strings

panned left and the trebles

panned right. What did you

play for that part, and how did

you capture such lush tones?

Oh, thanks! That’s actually a

6-string doubled with a guitar

playing Nashville tuning [a

6-string with the E, A, D, and

G strings tuned an octave higher

than normal]. When we made

The Weight Is a Gift with [producer]

Chris Walla, we were listening

to a lot of [Traveling Wilburys

and Beatles and Roy Orbison

producer] Jeff Lynne productions

and noticing how he puts

Nashville tuning on everything.

Which guitars did you use

for that, and why did you use

two guitars instead of a single

12-string to get that sound?

Because fingerpicking on a

12-string is a sloppier affair, and

I’m really not much of a fingerpicker.

I used a 1991 Gibson

J-200, and the Nashville tuning

was on a big, blonde Guild

F-50 jumbo.

One of the big lessons demonstrated

by these tracks is how

the different layers need to contrast—

rhythmically, texturally,

or tonally—and yet still lock in

and complement each other. For

instance, the middle section of

“When I Was Young” has these

anthemic, ringing chords on

electric guitar that give you an

image of a rock god in power

stance on a huge arena stage,

and it stands in such bold, stark

contrast to the lilting acoustic

beginning. How much time do

you spend thinking about and

working on contrasts like that?

I hope we’re not guilty of doing

the same thing over and over

again, but I always gravitate

toward certain things. I mean,

if a part is slow and big, I tend

to want to think in a Crazy

Horse way. Neil Young’s “Cortez

the Killer” [from 1975’s Zuma]

period—with those booming

chords—was a huge influence.

When I’m thinking that way,

I’ll go for this really saturated

sound and I won’t play much so

that the chords can really ring

out and bloom. It’s like when

you set a compressor the right

way on a crash cymbal. A lot of

people hit cymbals too hard so

they choke. That was a big thing

about [Led Zeppelin drummer

John] Bonham—he hit the

drums hard, but he didn’t hit the

cymbals hard. If you hit a crash

cymbal lightly, it’ll go whoooosh,

and I think guitars can be the

same way: If your amp’s really

singing, you can play less and let

the harmonics really do stuff.

Matthew Caws’ Gear

Guitars

1968 Gibson Les Paul Custom Black Beauty, 2011 Edwards LP-130, 1975 Gibson

Les Paul Standard, 1960 Les Paul Standard reissue, 1969 Telecaster, Fender Baritone

Jaguar, 1991 Gibson J-200, 1980 Guild F-50 (strung for Nashville tuning), 1971

Yamaha FG-180 (red-label Nippon Gakki version)

Amps

Two tweed 5E3-circuit Fender Deluxe clones made by John “J.J.” Jenkins of

TwangMaster Guitars, Fender 1965 Deluxe Reverb reissue with Jensen Special

Design speaker, early-’80s Marshall JCM800 50-watt head driving a 2x12 cabinet with

Celestions, early-’60s Silvertone Twin Twelve, THD 8 Ω (purple) Hot Plates on all amps

Effects

Fulltone OCD, Hughes & Kettner Rotosphere, Electro-Harmonix POG, MXR Dyna Comp

Strings, Picks, and Accessories

John Pearse .013 sets (acoustic), D’Addario .012 sets (electric), Jim Dunlop nylon .60 mm

Do you ever struggle with

having too many cool guitar

parts for a single song? How

do you know when to say,

“enough is enough”?

I don’t usually have too many

parts, but I can definitely have

too many tracks. At some point,

you have to go, “Okay, it’s getting

smaller.” The problem is that I’m

so addicted to doubling. But if

you’re, like, “Oh, let’s try this guitar

and this amp. And how about

these …,” before you know it,

you’ve got four tracks of rhythm

guitar—which can be okay if you

can control it in the mix. But

when you have too much, it starts

to get smaller [sounding]. The

transients are all getting squished,

because there are so many of

them—they’re blurring together.

So sometimes it does take a bit of

an effort to dial it back.

Your doubled guitar parts are

incredibly tight. Do you work

extra hard to track them that

way from the beginning, or do

you nudge them in Pro Tools

after the fact?

I’m not so into using Pro Tools

to move stuff around. I got my

big lesson on doubling with

Ric Ocasek on our first record:

Whenever we’d have a song with

a typical, here-comes-the-chorus,

kaboom-type of thing, we would

triple-track it with a Les Paul

and a Marshall. I’d do the first

track, and it was usually cool,

but for the second and third layers,

he’d make me do it, like, 15

times—until that first fraction

of a second hit like a wall. I’d hit

the chord on the second or third

track, and Ric would be, like,

“Yeah, that’s good. Do it again …

Good. Do it again … Good …

Do it again ….” And then I’d hit

one where it was just completely

invisible—and I’m a believer now.

When the stuff is really tight, it

just does something really special

to the impact of the song.