The other day my Grammy-winning engineer friend, Masa Fukudome, played me a CD he'd just purchased for recreational purposes. The first song began with an acoustic guitar and a whispering falsetto vocal. Pounding Bonham-style drums led into the second verse as the band joined in with rectified power chords and thundering bass. By the chorus, it was a full-frontal assault: Stacked, angry guitars chugged eighth-notes in tandem with the bass and double kick while the singer yelled like a scary devil/televangelist. Strangely, the intro, verse, chorus, solo, and whispery vocal/acoustic outro were all roughly the same volume. The band played great, the production was inventive, and the songs were good, but the whole experience was about 80-percent less cool because all the life had been compressed out of the music in the final mix and mastering.

As mesmerizing as music is, it comprises only a few elements. Depending on who's providing the definition, this short list includes rhythm, melody, harmony, timbre, form, and dynamics. That's not much to work with, but some musicians restrict themselves to even less. My guess is the death of dynamics came about from a fear of not being heard. Record companies, producers, and musicians all want their tracks to sound big on radio and TV, so they juice the volume and then compress the sound so even the quiet bits will cut. Alas, that totally jacks up the end product.

In orchestral music, dynamics are a hugely important part of the experience. Scores are peppered with pp, p, mp, mf, f, and ff—dynamic markings that indicate pianissimo (very soft) to fortissimo (very loud) and all points between. Extreme dynamics also define the sound of many post-rock guitar bands.

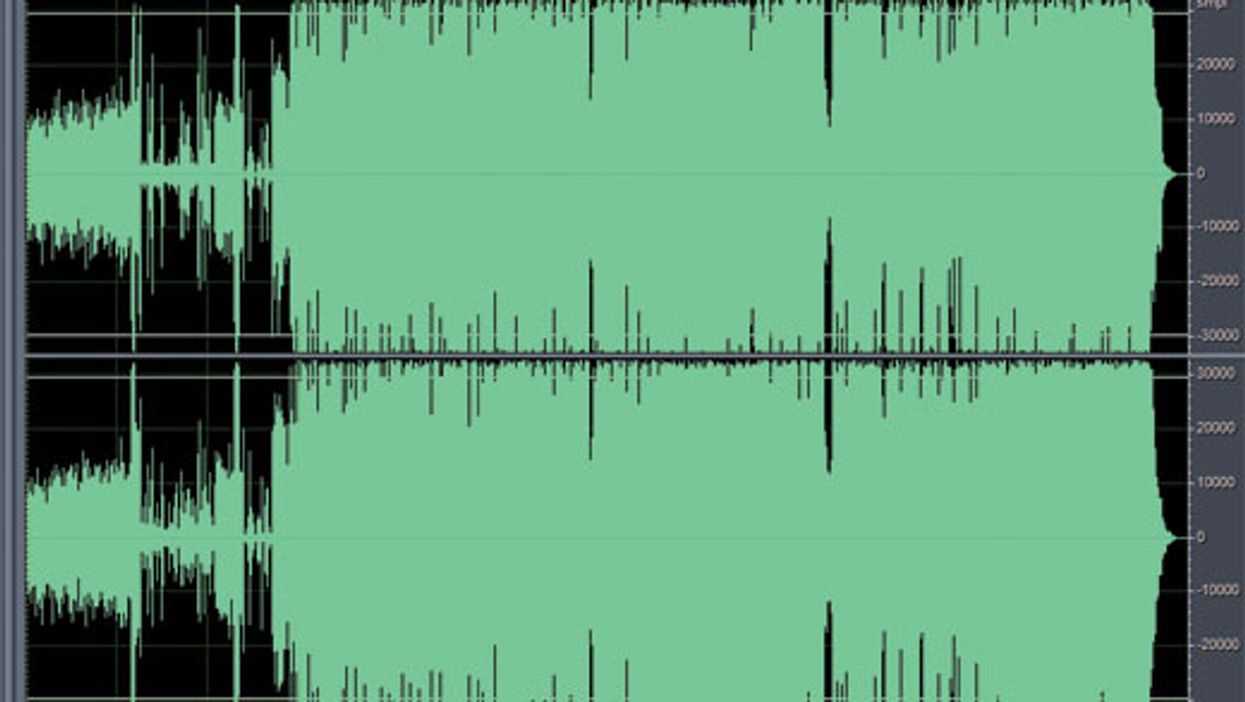

But today's pop music is mastered so all the levels are squashed to hover right below the red line of digital distortion. This gives us an emotionless ff all the time. Import a modern pop, rock, or country song into Pro Tools and look at the waveform. Instead of a sexy, curving thing that rises and falls with the volume, you'll see a nearly continuous fat, fuzzy rectangle. Now for contrast, examine the Beatles' “Oh! Darling" and you'll see the dB meter rise and fall as Paul McCartney works the vocal. Can you imagine how lame that awesome song would be with a dynamic-free performance?

When you get a chance, attend a concert by a world-class orchestra in an acoustically tuned venue. You'll be on the edge of your seat listening intently to a faint melody played by a solo flute over a few subtle strings and then—boom—80 other players come in loud and proud. The hairs will stand up on your head and then before you know it, the damn flute is lulling you to sleep again until the next ff outburst scares the crap out of you.

That's the power of dynamics. Regrettably, many modern drummers don't get it. Say “dynamics" to some and they'll respond, “Dynamics? I'm already playing as loud as I can." This puts us guitarists in the no-win position of trying to blow over them. Bass players can be equally difficult: Many set their volume so they can hear it far above everything else onstage, not realizing that because of the omnidirectional nature of low frequencies, they're burying the music for everyone else.

The other night while I was playing at Robert's Western World in Nashville, the steel player said, “Could you come down more when I'm soloing so I can use some dynamics?" I felt like such a turd! I'd been trying to hear myself over the drums but while doing so, I pretty much ruined the steeler's chance to communicate through his instrument. I also realized that I started all of my solos by stomping a get-loud pedal and cranking my guit's volume. It was all blow, blow, blow, then stop when somebody sings. Chagrinned, I spent the rest of the night trying to work my volume like a good Southern preacher.

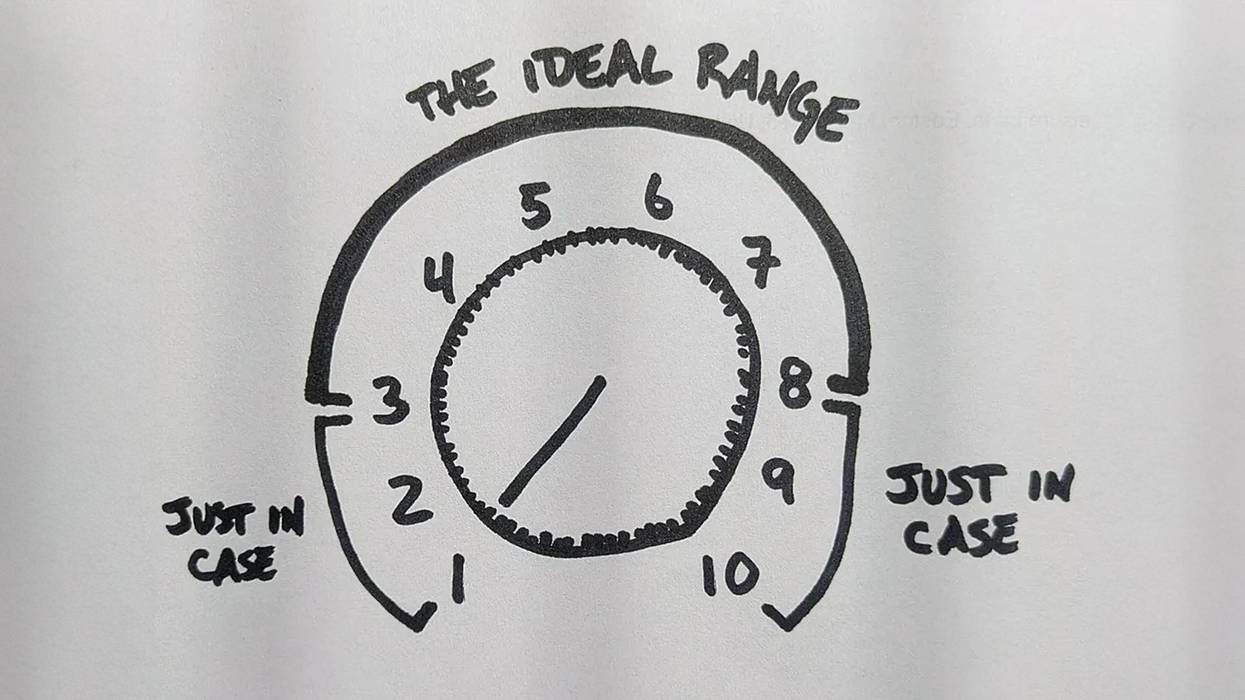

The next time you're playing with a band, try this: When it's time for your solo, turn around to the drums, crouch down, and start playing quietly. Hopefully the rest of the band will read what you're doing and come down with you. You'll notice that even the crowd will get quiet and start listening more closely. Then begin sneaking up your volume and posture until you rip the roof off the dump. Compared to the quiet stuff, your “loud" will seem so much louder. Check out Buddy Guy, who's not afraid to play so quietly you can hear his Strat acoustically onstage. When he has the whole room leaning in, desperately trying to hear what he's playing, he'll crank up the heat and melt faces in the front row. Be like Buddy—don't drown out the crowd, just make them stop talking because they want to listen.