Whether you navigate it consciously or unconsciously, guitar-rig building has multiple stages. In the beginning, it’s all possibilities and no responsibilities. The current state of the art and status of the market are such that nearly anything that you can conceive of is within your grasp. If you’d like your pedalboard to produce the sounds of yesterday, the guitar hive mind will provide you multiple methods. If you want to do something that’s never been done, the sheer volume of pedals and other gear that’s available makes for a set of permutations whose depths can likely never be fully sounded.

As a rig builder, I’m often brought in after the initial conception stage. The player has at least a general sense of what this pedalboard or rig has to be and do. There are lots of potential problems that can manifest at this point. A very common one plays out as follows: A young player (either in stage of life or stage in career) gets their first major gig. Their initial desire is to build the rig of their dreams— something with enough pedals and sounds to ensure there is next to no chance they won’t have what’s needed in every situation from stage to studio. This leads to a sort of feature creep as they add more pedals to deal with musical edge cases. “I’m going on the road with a mid-market Americana band, but one time 10 years ago, I sat in with a band to play ‘Shakedown Street.’ So, I should probably have an envelope filter.”

The result of this unfettered specification can be a pedalboard three sizes too large. For bigger touring outfits, any remotely reasonable size is manageable, as semi-trailers are spacious. But I can tell you from experience that inappropriately prepared players can open themselves up to chiding by bandmates and crew who might perceive the player as pretentious or, worse, clueless. The problem really comes to a head when this well-intentioned player now has to play the employer’s a-shade-over-three-minute 1–5–6–4 single at the Opry as a host of grizzled veterans stand in the wings wondering why there is a spaceship preparing for takeoff at the stage’s edge for an act that is going to come and go between commercial breaks.

Picking pedals for a gig means knowing the songs, arrangements, and having a producer’s ear.

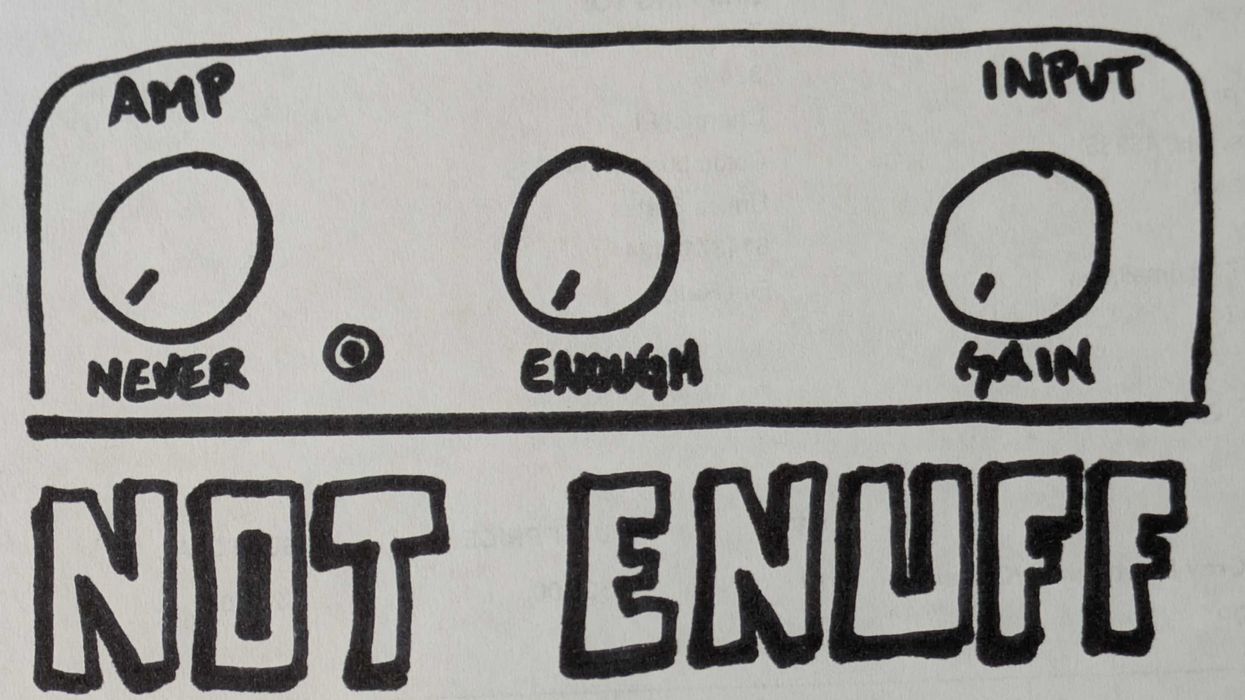

Is the rig “good?” Without a doubt. Is it “right?” In terms of essential simplicity, maybe not. During that initial design phase, having a very clearheaded understanding of what the board should not be is just as important as determining what the board should be. You might be thinking this overzealous gear response is strictly the domain of newbs and rookies, but you’d be wrong. I’ve sat in hour-long rig consults with some of the most recorded guitarists in history—card-carrying guitar heroes—and in the first conversational lull after arriving at the “final” plan, this supremely confident, completely secure player will say, “Is there anything else I should be putting in there?” The idea that we might be missing something is no respecter of persons.

I’ve been having this same conversation with guitarists of all ages and stages for over 20 years. Recently, it has gotten me thinking of a certain Swiss patent clerk who said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

So, how do we follow patent clerk Albert Einstein’s exhortation to keep it simple? Picking pedals for a gig means knowing the songs, arrangements, and having a producer’s ear for what sounds and parts are actually required to make it through a full set, a shortened direct-support position, or a one-off TV date. Having drive pedals that are useful separately and stacked can round out your tonal core. Adding your bread-and-butter modulation and time-based effects will keep that section from becoming too expansive. A multi-effect pedal can catch all those edge-case scenarios that would otherwise add low-utility square footage.

Consider a more modular approach where a primary board can have auxiliary boards patched into it to expand its utility and allow it to collapse in size easily when necessary. Don’t be afraid of adding what’s called for, I’ve built super complex rigs that were as simple as they could be, but don’t fall into the trap of thinking a single monolithic pedalboard setup is the only answer.