Tonemaster Joey Landreth takes PG through his current touring rig, from his Novo baritone to a trio of trusty Two-Rocks.

Canadian alt-country group the Bros. Landreth have become known for bringing not just layers of blues, rock, and eclectic modern influence to the traditional country sound, but for Joey Landreth’s depth as a guitarist and stunning tone on the instrument.

Built on a lifetime of brothers Joey and Dave’s absorbing classic country music, the band was launched with the release of 2013’s Let It Lie, through which they not-long-after made a mark on the scene when the album garnered a JUNO Award for Roots and Traditional Album of the Year in 2015. Following the release of 2019’s ’87, the group later received another major accolade when Bonnie Raitt covered Let It Lie’s “Made Up Mind” on her 2022 release, Just Like That…

While the original lineup included drummer Ryan Voth and pianist Alex Campbell, and the band has toured with guitarist Ariel Posen, the brothers have since taken a step back from the larger band arrangement to lead as a duo. Their latest, 2022’s Coming Home, spotlights the two in that dynamic, while featuring a few backing players.

Joey Landreth hung with John Bohlinger and the PG team before the Bros. Landreth’s show at Nashville’s Riverside Revival, where Landreth played some mind-blowing guitar and demoed his unique method for reproducing his studio sound live.Brought to you by D’Addario String Finder.

Golden Tradition

Landreth has been seen playing a Sorokin Goldtop for years. His new No. 1 is the Sorokin Pluma, handbuilt by Alex Sorokin in Edmonton, Alberta. “Alex is a master builder, and he has nothing but respect for the tradition of these guitars,” says Landreth. The Pluma features a one-piece Honduran mahogany neck and body, Eastern hard-rock maple top, hide-glue construction, and Ron Ellis LRPs pickups. It’s strung up with Stringjoy .019–.056 or .017–.054, depending on tuning.

Built Like a Mule

This Mulecaster was built in Saginaw, Michigan by Landreth’s good friend Matt Eich. Constructed with a metal body, it comes loaded with two benders, and according to Joey, Eich builds everything on the guitar (with the exception of the benders), including the pickups. “The first tune in our setlist is a song called ‘Forgiveness,’ and the benders are a big part of the hook,” Joey shares. “I can’t play that song on literally any guitar, so this guitar comes along to play that tune and a couple of other ones.” Strings are Stringjoy flatwounds, gauged .019–.056 or .017–.054, depending on tuning.

High-Strung Baritone

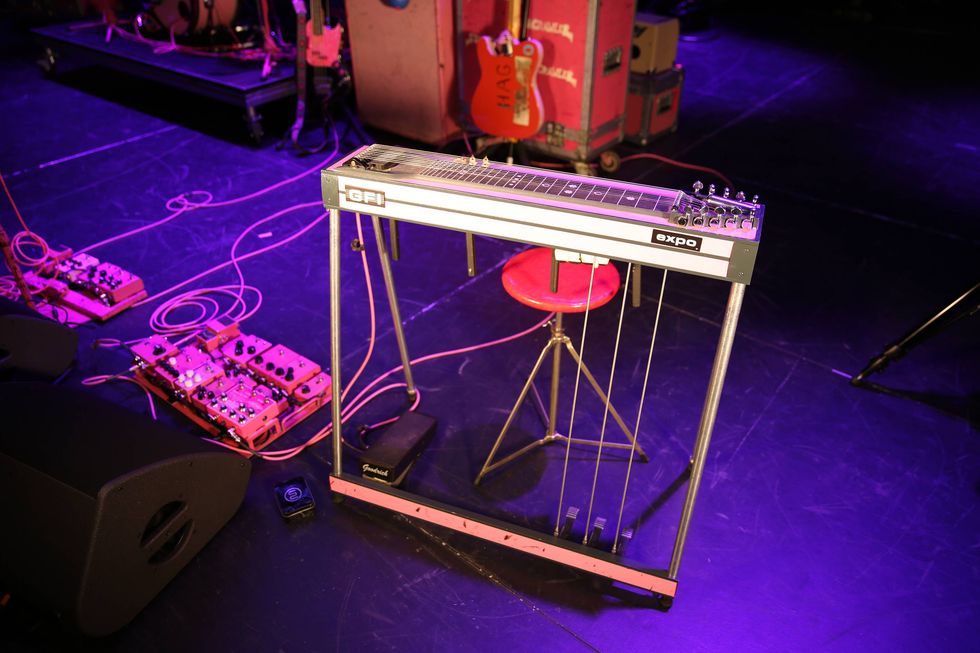

Joey mainly keeps this Novo baritone, which was built in Nashville and features Lollar pickups, in low open tunings. He’s worked with Stringjoy to get just the right strings to play comfortably in those tunings. “That's the thing about those guys,” he says, “is you can say, ‘I like .011s in E, what would be a comparable set of strings for D? And they’ll plop it into their computer and say, ‘This is what we think would be comparable.’” Joey asked the company for a set that would work with an Ab tuning on the baritone, and they hooked him up, but—“I have no idea what’s on this guitar. I hope I don't break a string.”

Landreth uses his Rock Slide signature slide, Paige Capos, and Blue Bell Straps, made in Spain. Landreth uses mostly Digiflex cables, but also has a few Caulfield cables as well as some made by Runway Audio Cables out of Nashville. As for picks, he doesn’t really have a preference.

Choice Circuits

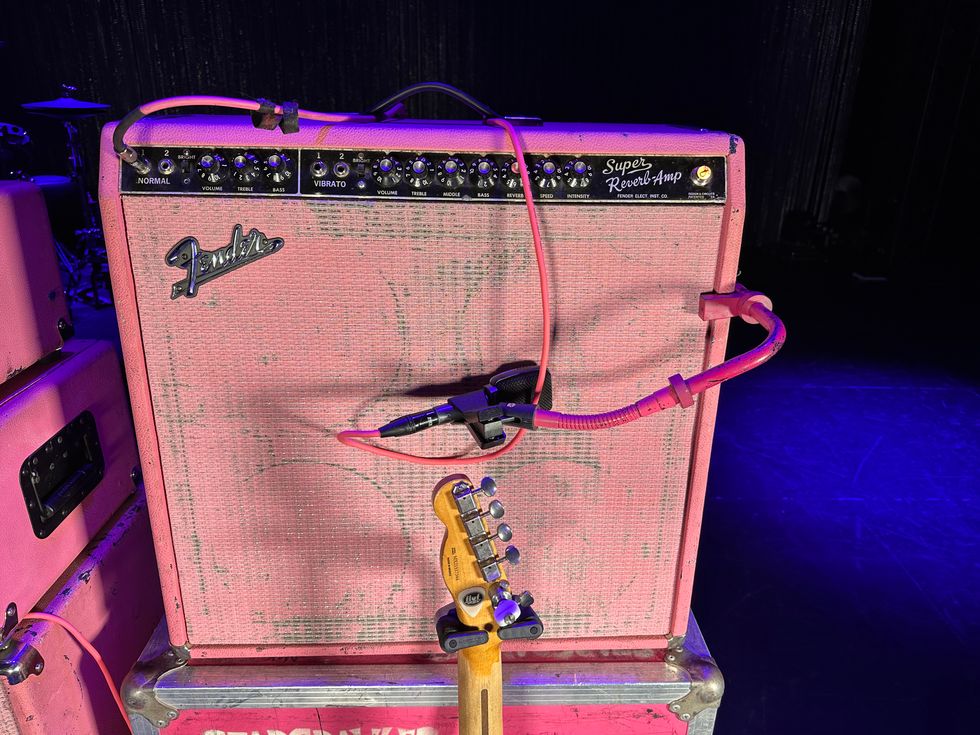

Landreth uses a three-amp combination, the center being his new signature Two-Rock, which only carries the dry signal. The development of the amp came out of a meeting with guitarist Josh Smith, who turned Joey onto Two-Rock’s tones after Landreth jammed with his model. Joey reached out to Two-Rock, and a few years later, the company agreed to work with him on an amp that included a complicated-to-install harmonic tremolo, on his request. When he was sent the third and final prototype, he says, “I plugged it in and legitimately shed a tear,” laughing. “It was like, ‘It’s beautiful.’”

The two other amps in Landreth’s trifecta are Two-Rock Studio Signatures. Where the first only carries dry effects, these two only carry wet. With 1x12 speakers, they’re considerably smaller. “They are killer little amps,” he says. “Part of the appeal is that, if we’re going to go do a quick press video or something, I can just grab one of those little guys … and we don’t have to unpack the entire van.”

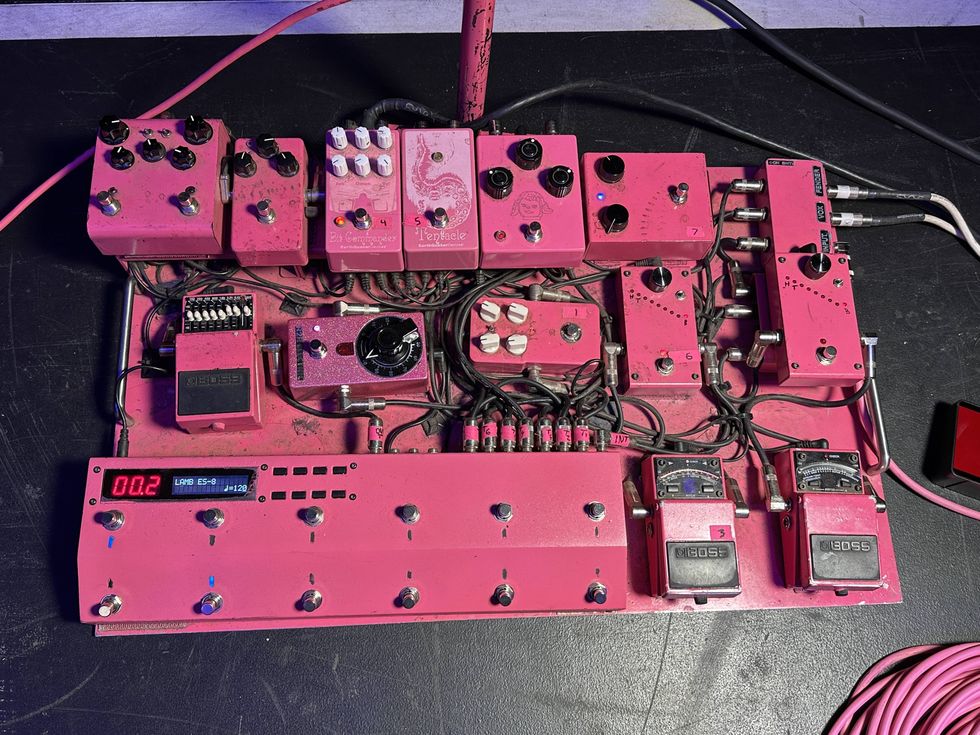

Joey Landreth's Pedalboard

Mounted on a pedalboard made in Melbourne, Australia, all of Joey’s pedals go directly into the GigRig G3, with the wet effects all going into a Morningstar ML10X that lives under the board. It allows Landreth to do more complex routing with custom routing for every preset, and also lets Landreth only use one stereo loop for all wet effects. Those pedals include the Empress Echosystem, Chase Bliss Thermae, Chase Bliss Blooper, Chase Bliss MOOD MkII, Chase Bliss Generation Loss, and Chase Bliss CXM 1978.

They all go into the ML10X which then goes into the GFI Duophony, which gives Landreth a parallel mixer with a ton of options, including gain for each individual loop. Landreth uses the Duophony as a master volume for all wet effects, which are set up on an expression roller that Landreth controls with a custom box that he built. The Duophony also allows Joey to add the dry signal back in, either by preset or just in real-time—which is ideal when Landreth uses a backline with only one or two amps.

Among Joey’s additional pedals is the Shnobel Tone VPJR tuner mod, plugged directly into the EXP input of the Chase Bliss Condor for volume and low pass filter control. The remainder of his board is made up of the Maxon SD-9, Fairfield Circuitry Randy’s Revenge, Fairfield Circuitry Shallow Water, DanDrive Bonk Machine, Mythos High Road Mini Fuzz, and Axess Electronics Obvious Boost/Overdrive.Shop Joey's Rig

Shop Lindsay's Rig

Shop Lindsay's Rig

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.