Many recording enthusiasts know Warm Audio for their well-regarded and affordable takes on otherwise unattainable classic studio microphones, preamps, and processors. Most of these imitate the handsome aesthetics of those units along with their functionality, which adds to the allure. Warm Audio ventured into pedal building a few years back with lovingly rendered versions of the Roland Jet Phaser and Foxx Tone Machine. This time out, though, they’ve taken on two less obscure pedals, the Lovepedal/Hermida Zendrive and Klon Centaur, in the form of the Warmdrive and Centavo, respectively.

Some of the language Warm Audio uses to describe the Warmdrive and Centavo pedals—like “accurate recreation” and “true reproduction”—is bound to raise eyebrows among circuit snobs. Yet both pedals are ruggedly built. Plenty of attention is paid to the cosmetic details. Both circuits are put together using sturdy through-hole boards and populated with reputable components. And there’s a general air of quality about them, both inside and out, that promises real road reliability which should squash a lot of the chagrin from naysayers.

In some ways, the company’s decision to build clones of two pedals that have been copied many times over is a curious one. But Warm Audio’s attention to aesthetic details will no doubt entice cost-conscious enthusiasts chasing both the sound and visual cachet attached to these historically important effects.

Warmdrive

The original Zendrive was created by Alfonso Hermida in the mid ’00s as an attempt to re-create Robben Ford’s hallowed Dumble-driven lead tones in an overdrive pedal. That remains a lofty goal. But many players agree that Hermida succeeded just about as well as one could. The results were good enough for Ford himself, who frequently uses a Zendrive with non-Dumble amps (often a Fender Twin Reverb).

The Warmdrive control layout is identical to that of the Zendrive, and includes gain, volume, tone, and voice knobs. The latter is a versatile control that moves the pedal’s overall character between dark and bright tones in a more expansive way than you experience using a typical high- or low-pass-filter-based tone knob. Signal-sweetening gubbins include 1N34A germanium diodes, 2N7000 MOSFETs, and an NE5532 op-amp. The steel enclosure and true-bypass switch feel more than solid enough to survive repeated stomping. The cosmetics, in typical Warm Audio fashion, imitate the original.

Dum Dum Drive

With a Gibson Les Paul, Fender Telecaster, ’66 Fender Princeton combo, and 65amps London head and 2x12 cab, the Warmdrive was a fast track to the kind of Dumble-y, creamy saturation that’s kept players drooling through the decades. I suspect even cynics will be smiling when they slide into sustain-driven fusion improvs.

The Warmdrive is a thick, chewy overdrive at heart, but moves easily from smooth and warm to crisp and crackling, depending on where you set the voice knob. And there’s lots of room to fine-tune further using the tone control. There’s also plenty of range in the gain and level controls, which makes the pedal capable of much more than full-on lead tones. It’s a surprisingly good low-gain drive as a result. Even so, the real treats are in the near pedal-to-the-metal settings. Setting the gain around 2 o’clock, the volume around 11 o’clock, and tone and voice pretty close to noon makes a sound I could truly get lost in. I didn’t think about its Dumble-imitating origins, or how it sounded compared to a Dumble, or for that matter a Zendrive. I just knew it sounded great. If you want to feel like Robben Ford for a few minutes, this is an easy way to get there.

Centavo

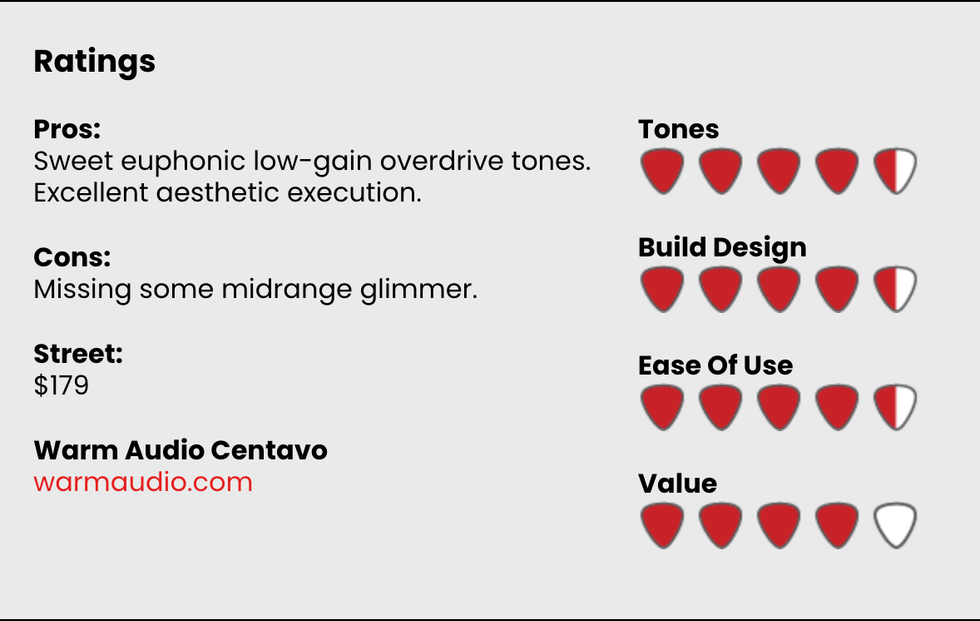

Cloning a pedal that’s unavailable in its original form (and prohibitively costly when you find one) is generally a service to the guitar community. In the case of the Klon, however, there are enough klones, and hype around them, that the addition of yet another will probably induce a few eye rolls. That said, the ongoing, often raging, debate over which klone clones the Klon best, indicates there’s still room for anyone that wants to take a shot at building a better, more accurate one.

To date, only one klone I know of comes in an accurate die-cast enclosure like the box that houses the Centavo: the well-regarded Centura from Ceriatone Amplification of Malaysia. So, Warm Audio’s insistence on vintage accuracy will be a boon for players seeking the original’s handsome look at a fair price. The 6.75" x 5" x 2.25" dimensions, though, mean itmight be less appealing to those eager to conserve real-estate on crowded boards.

Elsewhere, Warm Audio chased authenticity pretty relentlessly. Like the original, the Centavo uses buffered bypass, TL072 op-amps, and a charge-pump voltage regulator. The oxblood pointer knobs for gain, treble, and output are another nice vintage touch that looks great. Warm Audio did take one very practical liberty with original design in the form of a MOD switch, which is situated between the input and output on the pedal’s crown and extends the circuit’s low-end response.

Chasing Mythical Beasts

Tested via the same guitars and amps used for the Warmdrive evaluation, the Centavo provides many reminders of why the original Klon became so beloved in the first place. For me, at least, the tastiest function, just as on the original, is when it’s used as a near-clean or just slightly dirty boost. Even at unity gain it sounds excellent, which is apparent just as soon as you turn it off. If the Centavo had a photo filter equivalent, it would be one that illuminates everything with golden-hour light. Everything you hear is essentially the same—just somehow more magical.

When you wind up the gain for a more lead/overdrive setting, the Centavo doesn’t disappoint. It can sound a touch furry and woofy at times and is occasionally a little ragged around the edges. Yet it still adds loads of character to lead lines. Though purists might be bummed by its inclusion, I found the low-end lift from the MOD switch useful—particularly at lower gain settings, where it fills out the bottom end especially well. In general, though, the MOD switch’s effect on the output is subtle and doesn’t overpower the Centavo’s basic voice. If there are any noteworthy audible differences between the Centavo and an original Klon, it might be the Centavo’s lack of midrange glimmer, a quality that, for me, distinguishes the Klon Centaur. Maybe that’s why originals are $5,000 these days. But, man, that’s a lot of money for a little extra midrange!

The Verdict

Both of these new pedals from Warm Audio are well-built and carefully executed renditions of their inspirations and deliver very close approximations of the target sounds. If they aren’t dead on, and few clones ever are, they certainly get very close for extremely reasonable money, both yielding dynamic overdrive regardless of price. That they do so much to deliver the visual appeal of the originals only sweetens the deal.