Linkin Park’s Brad Delson caught me by surprise in the lobby of Larrabee, the North Hollywood, California, studio where he was working on a new record, The Hunting Party. His band’s angst-ridden lyrics and thick, ominous guitar parts suggested that Delson might be on the disaffected side, with a rebellious appearance. But he was gracious and approachable—beaming, even. Sporting a tidy hairdo, beard, and horn-rimmed eyeglasses, he looked less like a purveyor of nü metal than a cool grad student.

“Follow me around the pool table,” he said, leading me into the control room, clearly excited to show off his latest work. The room was immaculate, everything arranged just so. There were two boats of guitars that seemed to be organized for quick and easy access. On the mixing board four different-colored Sharpies were lined up perfectly. A pair of Muppet Show dolls, Statler and Waldorf, surveyed the scene from atop a corner shelf. Delson, who produced the record with his band mate and co-guitarist Mike Shinoda, sank into in a black Aeron chair behind the board. He looked bright-eyed despite long studio hours.

“We’ve been here five or six days every week for about five months,” he said. “This week [drummer] Rob [Bourdon] and Mike are recording drums to tape at EastWest, and I’m here on my own working on other aspects of songs.”

I make all day.” —Brad Delson

It’s a new methodology for the band: writing from scratch while recording. On their first two albums, Hybrid Theory (2000) and Meteora (2003), Linkin Park worked in a more traditional way, writing songs before demoing them, and then rerecording everything in the studio. But the band learned that careful preparation didn’t necessarily yield the most satisfying results.

“When we worked with [producer] Rick Rubin [for 2007’s Minutes to Midnight, 2010’s A Thousand Suns, and 2012’s Living Things] we brought him a bunch of demos along with the recorded versions that we’d spent days working on in a perfectly good studio environment,” recalled Delson. “When Rick A/B’d the versions, he always thought the demos were more compelling. That was an expensive and painful lesson.”

But for The Hunting Party Linkin Park used the studio as a compositional tool, recording as inspiration struck, compiling the best bits and pieces, and stitching them together as new songs. “Early in the process, Mike wrote a bunch of demos—introverted, indie-sounding stuff inspired by what you hear on the radio these days,” said Delson. “But we threw them all away in favor of making a more personal record, something more visceral and aggressive in a way that only we could do.”

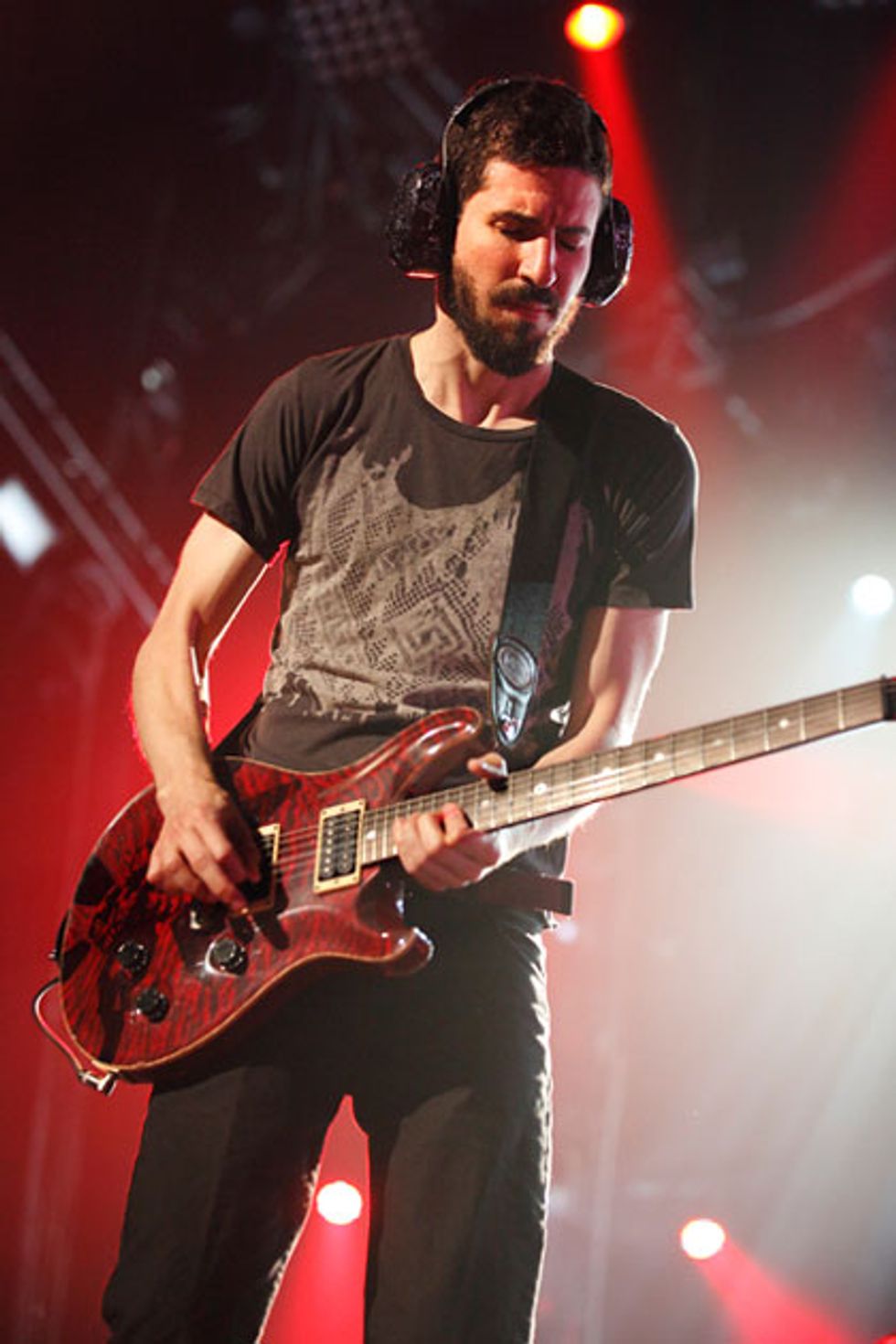

Delson rocking out during a show at the First Midwest Bank Ampitheater in Tinley Park, IL,

on August 24, 2012.

This off-the-cuff approach left open the possibility of happy accidents, explains Delson: “Something unintentional might be the coolest sound I make all day, and knowing how to allow those mistakes to happen and to shape them potentially makes for some great music. We’re trying to approach things with openness and childlike wonder. I just dive in and play a lot of guitar every day here in the studio. I might freely improvise riffs and noise to a fast click track for an hour, and then go back and sort through the recording. Sorting is so much more time-consuming than playing. But when I hear something I like, I say ‘That!’ and build layers around it.”

In the past, Delson often labored to compose the perfect backdrop for a track, only to discover that it didn’t quite work as a song. This time, after assembling a rough collection of riffs, he would submit the work to singer Chester Bennington for consideration. “We used to record the vocals last,” says Delson, “but now we do that closer to the beginning of the process, so we know if a track will survive as a song. It could have the coolest musical elements, but if doesn’t lend itself to a great vocal, then it’s time to move on to the next thing.”

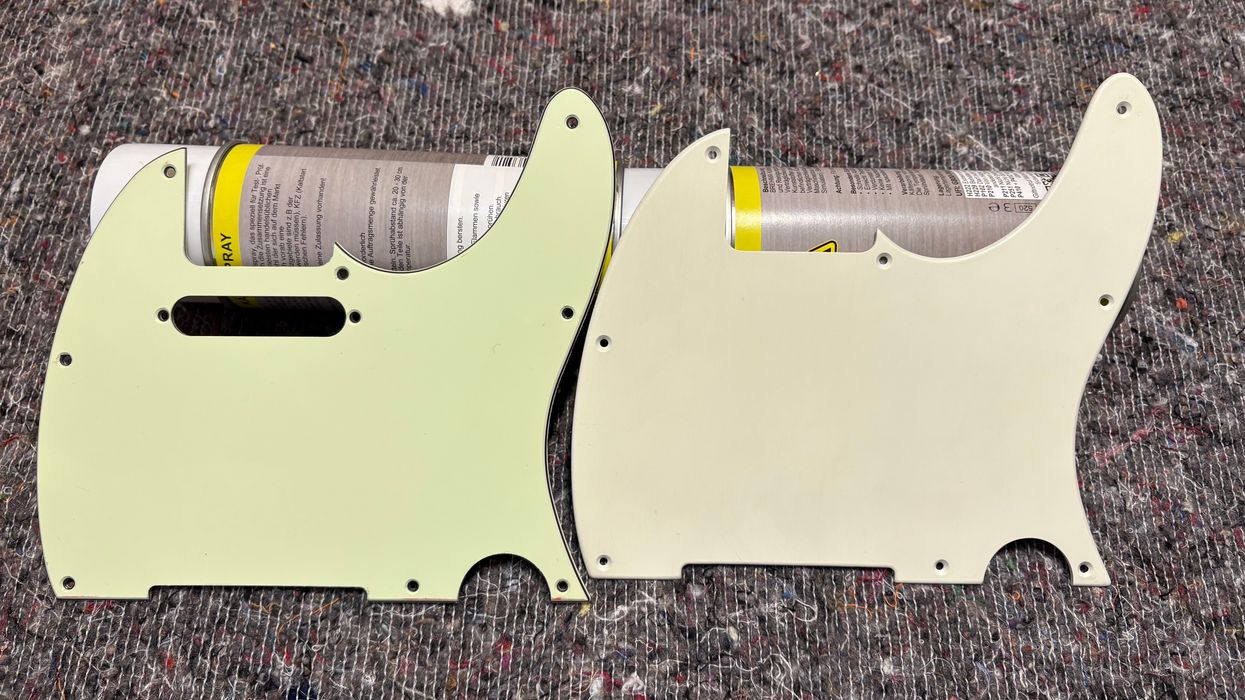

A collage of Delson's workhorses that included several custom PRS models and two well-loved Strats.

Sensing I was curious about his armada of guitars, Delson pulled a few favorites from their boats. He talked about how much he’d enjoyed using unfamiliar instruments like a 1973 Fender Mustang in a competition blue finish and a 1970 Gibson ES-335 with its walnut-colored stain. Seeing that a 1978 Gibson SG was absent from one of the racks, he chided his cohort. “Mike keeps taking the choice stuff to EastWest,” he said, chuckling.

Delson was relieved to see that Shinoda hadn’t made off with a guitar belonging to Ethan Mates, the record’s chief engineer: a reissue Fender 1962 Stratocaster from the Fender Custom Shop’s Master Built series, made by master builder Jason Smith in a relic Coral Pink finish. Delson was so taken with this guitar that he used it extensively on the record. He retrieved it from the rack and tremolo-picked a D natural minor scale. “I’m not sure whether it’s the action or the setup, but this guitar feels amazing to me,” he said. “It’s super versatile for lead and for rhythm, and it has this messy wildness to it that feels right for this record.”

Delson lowered the Stratocaster’s sixth string down to D and played an aggressive palm-muted power-chord progression. “It would be most intuitive to play a heavy passage like that on a guitar with double humbuckers, but I like to be contrary. On the Strat it becomes a different thing. It almost sounds like Helmet.”

The Hunting Party: An Engineer’s Take

Engineer/Producer Ethan Mates has collaborated with Linkin Park since 2006. In his own words, he details some of the recording techniques used on the band’s new album.We took a much more live, playing-centric approach to writing and tracking this record, as opposed to the more electronic style we used on the last couple of albums. We set out not to fall back on the same old guitar tones we’d used for the past six years. We started by creating a small collection of core tones to be used in a sonically consistent way throughout the record.

Delson's two racks of gear.

The core sound is created through Orange, Bogner, and Engl amps, and we’re also using a Chandler amp for overdubs and higher parts. Generally we have three microphones on each cab—either a Shure SM57 or Heill PR 30 next to a Sennheiser 421, and then either a ribbon mic like a Royer R-121 ribbon or a Neumann FET47, to capture a fullness of sound. We use pretty standard miking techniques, close-miked for the most punk rock, in-your-face sound, although sometimes for an ambient sound we use a room mic on the drums, or throw loudspeaker cabs in the live room and mic those.

In front of the guitar chain we’ve kept things simple, using the Z.Vex Super Hard-On, or the Z.Vex Mastotron for really chunky rhythm parts. We discovered that the Mastotron makes a really cool sound when the battery is running out, so we’ve been gathering as many dying 9-volts as we can find.

On top of all that, we’ve been drawing from a much broader palette of tones. A lot of times Brad likes big stereo washes in the chorus, so we experiment by stringing together a bunch of different reverbs and delays, sometimes using two different heads with a different effect chain in each one. Also, Brad likes using the Electro-Harmonix HOG for synth-like sounds. We’ve been using all of these tools to breath new life into Linkin Park’s sound. —Ethan Mates

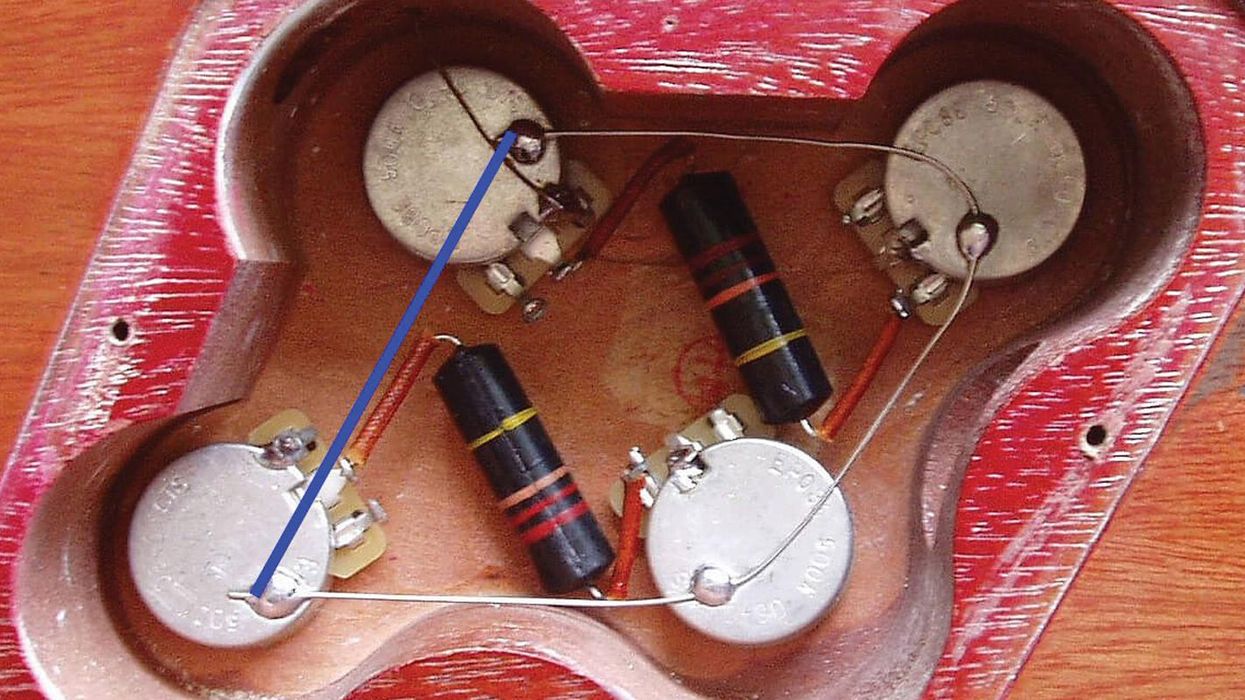

Delson is most closely associated with the PRS Custom 24, and despite his new affinity for the Stratocaster, he hasn’t turned his back on this old companion. “I love the PRS,” he said, eyeing the axe tenderly. “It’s always served me so well for live work, and it’s been really cool to combine its timbres with the Strat’s for recording.”

Next Delson directed me into a hallway, where he opened a large cupboard housing shelves and shelves of stompboxes. On the wall behind it were framed aphorisms by musical heavyweights. (“A song is anything that can walk by itself.” —Bob Dylan … “Well, if you find a note tonight that sounds good, play the same damn note every night!” —Count Basie.)

“Most of these pedals are Ethan’s,” said Delson. “He’s always scouring eBay and has assembled this sick collection. A lot of them are strange and rare, and many are customized. There are times when an arrangement calls for something out of the ordinary, and Ethan comes back here and chooses a bunch of pedals to curate a one-of-a-kind sound. In some instances you can’t even tell it’s guitar.” He pointed out the main pedals used on the new record, including a Z.Vex Super Hard-On, an Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail Reverb, and a Dr. Scientist Reverberator.

Brad Delson rocks out live with Linkin Park in 2012 on one of his special-made PRS Custom 24s. Photo by Ken Settle.

Delson opened the door to a sound room to show his amps. “Be sure not to knock any of the mikes,” cautioned Delson. In this wood-paneled room four separate stations housed brawny modern amps: an Orange TH100 head through an Orange 2x12 cabinet with Celestion Vintage 30 speakers, miked with a Heil PR 30, a Sennheiser MD 421, and a Royer R-121; a Chandler GAV19T head through an Orange 1x12 cabinet with a Vintage 30, miked with a Mojave MA-100 and a Neumann FET47; an Engl Fireball 100 through a Marshall 1960 cabinet, miked with a Shure SM57, an MD 421, and an FET47; and a Bogner Customized Twin Jet through a Bogner Ubercab, miked with a PR 30, an MD 421, and an R-121.

“It’s great to have a setup where I can run combinations of heads and cabs simultaneously to get the most appropriate tone, or do something more straightforward like record just one cabinet with two mikes,” said Delson.

Brad Delson's Studio Gear

Guitars

Fender Custom Shop 1962 Stratocaster (built by Jason Smith)

1978 Gibson SG Standard

MJT Telecaster

PRS Custom 24

PRS SE245

Amps

Bogner Twin Jet

Chandler GAV19T

Engl Fireball 100

Orange TH100

Effects

Caroline Guitar Company Kilobyte

Dr. Scientist Reverberator

Electro-Harmonix HOG

EarthQuaker Devices Disaster Transport SR

EarthQuaker Devices Hummingbird

Electro-Harmonix Holy Grail

Red Panda Particle

Strymon BigSky

Z.Vex Super Hard-On

Z.Vex Mastotron

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL110 strings (.010–.046)

Dunlop Tortex Wedge .73 mm picks

He led me back to the control room and seated me in the Aeron chair, showing me how to adjust the board’s master volume control. Then the album’s editor, Josh Newell (an intense-looking gentleman with a shaved head and an obvious enthusiasm for body art), took over while Delson ducked out of the room. Newell played me seven songs from the new album, quietly announcing each title.

Listening to these raw mixes, it was evident that the winning strategy Linkin Park established on Hybrid Theory—dovetailing spoken verses with melodic choruses—hadn’t been discarded. But on all levels there was new depth to the music in the form of lengthier interludes, greater harmonic diversity, and uncanny guitar sounds that made way for brief, fitful solos.

Delson returned and said he felt satisfied by the guitar’s primacy on the new music. “On the last few records I certainly played guitar in the studio, but I’d been focusing on other instruments. I’ve been playing guitar since I was 12, and it had become fascinating to learn keyboards, programming, and Pro Tools, which is like an instrument in itself. But these songs are all about rediscovering the guitar and having a lot of fun with it.”

We talked about the record’s compact solos, which, despite their brevity, reveal Delson’s formidable guitar skills and penchant for spontaneity. “There’s an unpredictability to these songs that lends itself to me just picking up a guitar and playing insanity,” he said. “Nothing is preplanned. For some of the faster solos I warm up, but not in an overtly methodical way. If I want to record a solo over at a fast tempo, I just noodle on that Strat for an hour until I’m hyper-fast. I don’t want to merge onto the highway at 15 miles per hour. I want to be at full speed by the time I get thrown on to it.”

On that note, it was time for me to hit the highway. Delson led me to the door and then he picked up the Stratocaster, eager to return to his craft.