Many years ago, before I had inklings of writing about and researching guitars, I had an eye for the unique—weird, strange, and odd artistic flair that I seemed to find in random things. Vintage car parts held my attention for a while, and even though I had only rudimentary knowledge, I still enjoyed designs and how I could fit them together. Like early hot rods or motorcycle choppers, I saw an intoxicating beauty in what some folks would call “outsider” art.

Additionally, I grew up near Nazareth, Pennsylvania, home of Martin guitars and the Andretti family! Interestingly, there were a few racetracks (often called speedways) around, which were like oval dirt tracks where all sorts of cars raced around and turned the attendees into mudballs! At the time, my parents had an AMC Gremlin and, with tons of modifications, many of those cars were transformed into racers. It was like I drove around in a hot rod with no seat belts! Good times.

“What’s the big deal if this pickup was supposed to be in the bridge position, or that pickup was wired out-of-phase?”

Of course, as my attention turned towards electric guitars, I saw the opportunity for hot-rodding and modifying these instruments. Why? Because the guitars I found were often unplayable, and sometimes had dead pickups. I mean, what’s the big deal if this pickup was supposed to be in the bridge position, or that pickup was wired out-of-phase? These details meant nothing to my obsessive mind. I just wanted to create guitars and make noise.

Now, much earlier than my fiddlings, there was a fellow from South Jersey (also near me) that was already repairing pickups and experimenting with wire, winding, and construction techniques. This gentle soul, one of the nicest guys I’ve ever met, is the amazing Seymour Duncan! I don’t have to list all of his accomplishments and accolades. He’s a true living legend, and has had a massive impact on music, repair work, and guitar tone. But I would argue that Seymour is one of the earliest practitioners of hot-rodding guitars. Think about it: Back in the day, when a pickup failed, it was simply replaced with another factory part. But Seymour actually repaired pickups and noticed all sorts of differences. I’m sure it also helped that he’s an excellent player with a good ear for tone—whereas me, I didn’t have an ear at all.

So what can a kid do when there aren’t any repair spots nearby, and he hasn’t the ability to differentiate between good tones or bad ones? Well, you just go nuts like I did, and listen to hundreds of guitars and pickups! The good, bad, and ugly of 6-strings all passed through my hands, and eventually I developed a certain “type” of ear. Not Seymour-level, but maybe like, empty-beer-can level? I started to listen for pickups that had a presence and zing. I dug aggressive sounds, but I also enjoyed hearing a touch of echo. Eventually, I settled on pickups that were constantly on the verge of losing it, exploding without your palm grounding the electronics, constantly on the edge of feedback! For me, it was akin to driving a car with a manual transmission. I felt more in tune with a guitar if it was giving me input, dig?

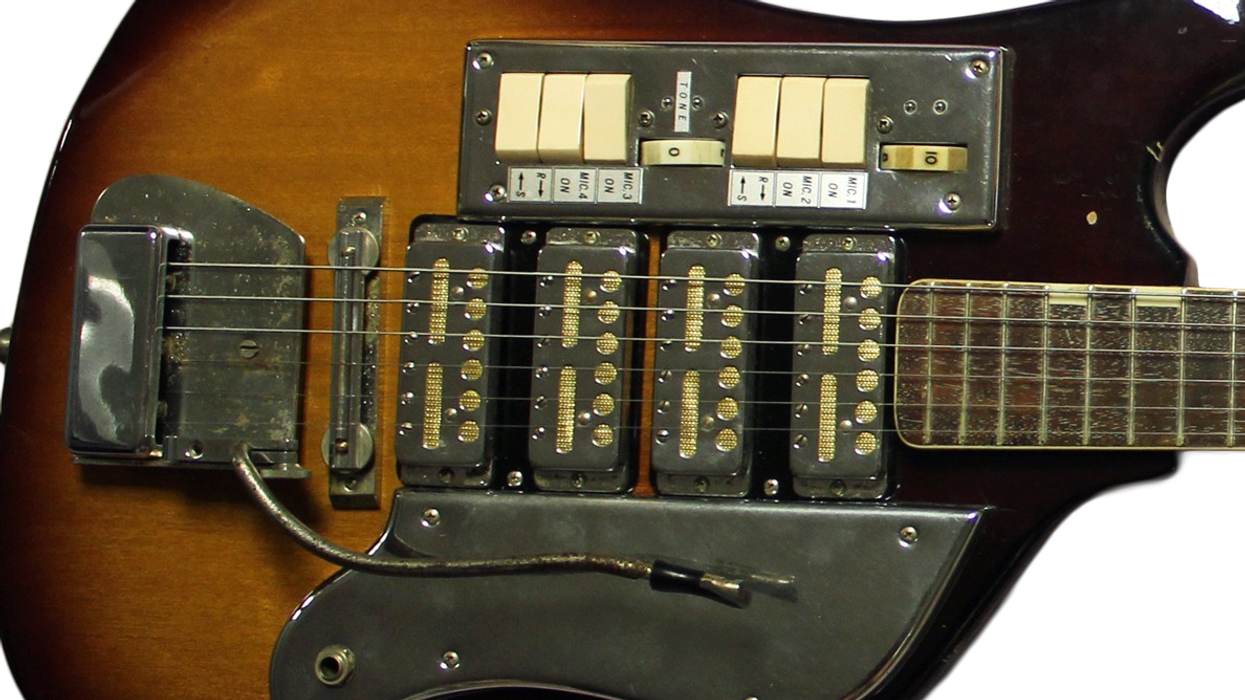

Out of all the pickups I’ve heard, among my favorites are the earliest gold-foil ones made by Teisco. There are tons of gold-foil variants hailing from 1960s Japan, but the very first ones, produced between 1963 and 1965, are the best to my ears. It’s probably why older players would hot-rod guitars with these units. So for this month, I’m giving you a glimpse of one of my hot rods with my gold-foils. This guitar, dubbed the “Pumpkin,” is one of the easier builds you can do. Vintage and many reissue gold-foils were surface-mount, so you can easily adapt a tried-and-true template like a Fender Stratocaster. It’s like using the old Ford Model A, because you have a solid base, and don’t have to modify too much. Everything on mine here is mostly genuine Fender, except for the electronics.

Another easy way to mess around is with the guitar’s pot values, but then again, I’m getting a bit out of my pay grade. For those kinds of questions, you’d have to check with Seymour!

Then, in the dream, I “awoke” and realized I was back in my bedroom, and it was all just a dream. The kicker is that I was still dreaming, because that “paddle” guitar was suddenly in my hands—then I woke up for real! How about that misadventure?

Then, in the dream, I “awoke” and realized I was back in my bedroom, and it was all just a dream. The kicker is that I was still dreaming, because that “paddle” guitar was suddenly in my hands—then I woke up for real! How about that misadventure?