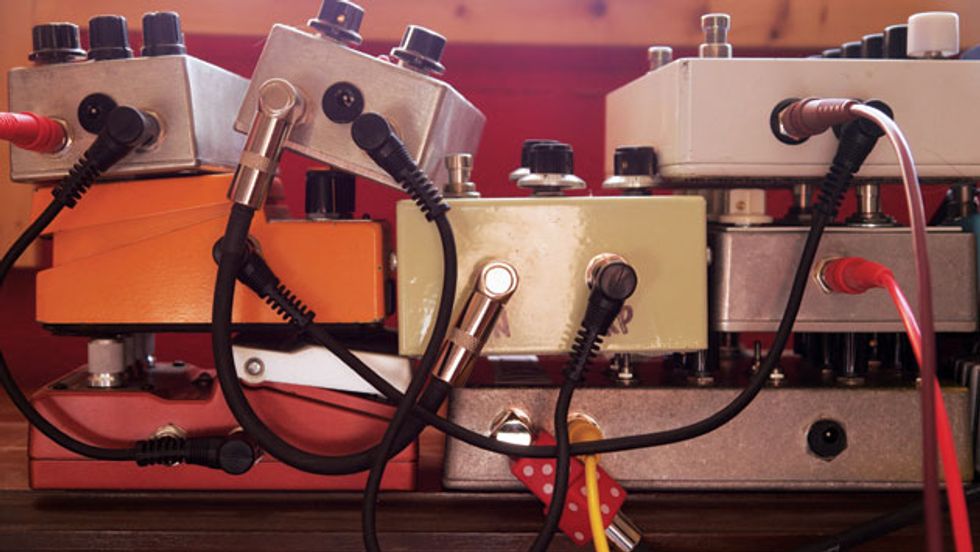

Confession: I am a pretty basic guitarist, if a noisy, feedback-loving one. As such, I follow a fairly standard order on my pedalboard. Wah, distortion, pitch, modulation (including my volume pedal), delay, reverb, looper. I may have more, and weirder, pedals than the average guy, but the order has been pretty much the same since the beginning.

A couple years ago we got an email at Dwarfcraft asking how one of our distortion pedals handled reverb.

"What?” I thought. “Why would it ever take reverb?” Turns out, the customer was amazingly, wonderfully right. The wall of sound created by a guitar into reverb and then a distortion pushed the dirt pedal to its max. As the reverberated signal decayed, the distortion accentuated different harmonics, animating the single chord I played.

No Wrong Answers

Everyone says that there are no rules about how to arrange your pedalboard, right before they tell you their five rules, and why everything else is wrong. Years ago I read a blog post where the author mentioned that reverb into distortion was essentially wrong, and was “likely” to sound muddy, but he hadn’t tried it. Maybe he would have hated it, but maybe it would have been exactly the sound he was looking for. It was for me.

We get questioned about pedal chain order a lot, and the answer is that you have to try it with your set up to know what you like. There is no wrong answer, with the possible exception of treble boosters. If I had a dollar for every time I thought, “Gee whiz, that guitarist needs more treble,” I would have negative one billion dollars. (Just kidding—mostly.)

The key to placement is knowing what each pedal does with the signal. Some pedals don’t like going after a buffer. Some pedals make noise even when bypassed, something you might not notice until you kick on a dirt pedal later in the chain.

I’ve always put my wah before distortion, because I love sweeping through all those harmonics and having the distortion pedal exaggerate them even further. Now, the fine folks in Portishead seem to prefer the wah after distortion. That’s also a great choice, because it allows the wah to process all the frequencies coming out of the dirt pedal for a very vocal sound.

How to Ruin Everything

Since my reverb-into-distortion revelation, I have found a few other tricks that most pedal nerds would call “wrong.” There’s one technique I like to call the “ruin everything.” You put a big, mean distortion at the end of your pedal chain. You can use it now and then, or just leave it off until the magic moment when you arrive at the end of the last song in the set, the crowd is eating it up, and you know you’re going to hang on that last chord forever while the drummer rolls around his kit like a dump truck full of cookware falling down a mountain. Kick on the “ruin everything” pedal. It will smash, exaggerate, and ruin all your other pedals in a monstrous wall of fury. Congratulations, you’ve just won the feedback outro!

Another great source of new sounds is digital artifacts. In a recent studio session I realized I had hooked up four or five digital pedals. Just for fun, I turned them all on and dialed in the most chaotic possible settings. I was rewarded with a choir of digital angels, but all the angels were singing different songs. Since we were going for a Motown feel, I didn’t think this broken robot choir would fit anywhere, but I recorded a minute or so for posterity. As it turned out, it made a lovely (quietly mixed) pad for an intro and interlude.

Break a Rule, Change the World

As guitarists, we should always be wary of rules and conventions. After all, the sound of guitar actually comes from that hollow wood thing in the corner of your room, with the big metal strings and a hole in the middle. The moment we went electric we were blazing new territory. Distortion on guitar was just an accident that we embraced. That bit of rule breaking led us to a whole new world, one where “distorted” is just how a guitar sounds in many people’s minds.