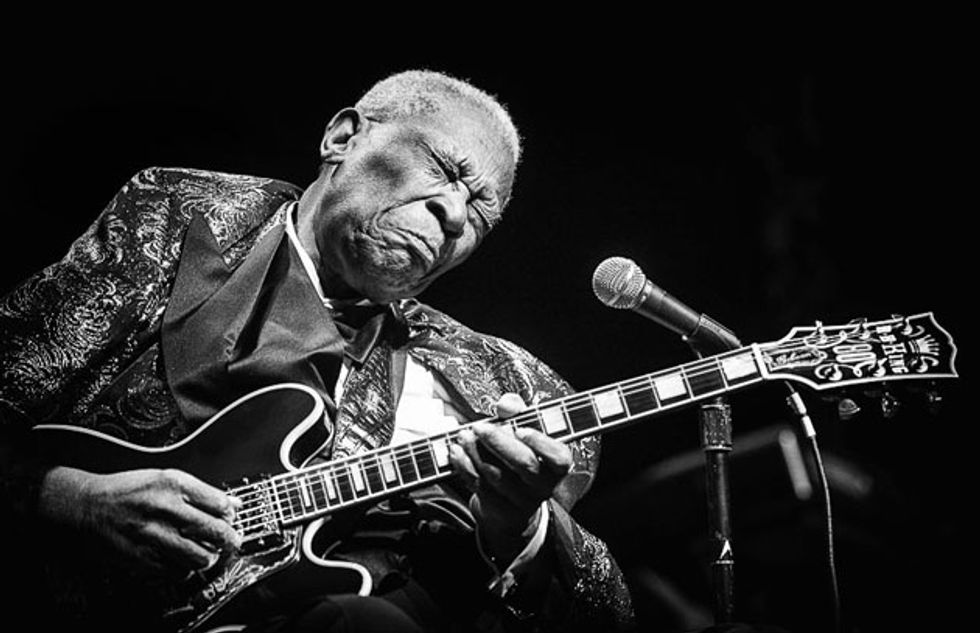

Photo by Jerome Brunet.

Las Vegas, Nevada (May 15, 2015). Guitarists and blues fans around the world are mourning the loss of B.B. King, who died last night in Las Vegas. Two weeks ago, he was admitted to home hospice after suffering from dehydration and complications brought on by type 2 diabetes. After a valiant struggle, King succumbed to the disease at age 89.

Perhaps millions of words have been written about Riley B. King—the “Beale Street Blues Boy”—and his amazing journey that began in 1925 on a cotton plantation in Mississippi. His early career in Memphis and rise to worldwide fame as “King of the Blues” is lovingly documented in the book he cowrote with historian Dick Waterman, The B.B. King Treasures.

In this extraordinary memoir, photos, posters, and memorabilia from King’s personal archives illustrate a life well lived by a boy who fell in love with the guitar and followed his dreams to become the world’s greatest blues ambassador. If you’re interested in exploring the details of his life, track down this beautiful volume and read it while listening to Live at the Regal—the 1964 album that inspired so many rock guitarists who came up in the ’60s.

I was one of those guitarists. While in high school circa 1967, I discovered B.B. King by way of two of my heroes, Michael Bloomfield and Eric Clapton. They, like many other great emerging guitarists of the day, never missed an opportunity to give King credit for showing us all how to bend strings, add sweet vibrato to a keening note, and how to slice through an ensemble with a fat, yet cutting humbucker tone. When I first saw King and his horn band in Boston in 1970, I was astounded by his powerful sound—not loud, but penetrating—and the joyous swing that permeated every phrase he played.

In June 2000, I found myself sitting across a table from King at his New York City nightclub. I was interviewing him on the morning the doors would open for the first time. King was a large man, and he took up most of the red vinyl booth facing my microphone and recorder. But even larger was his presence. Relaxed and jovial, he exuded charm. But here also was a man who’d faced intense racial discrimination in the early days (imagine being required to enter a club you’re headlining through its back door). This was a man who’d fought his way into the music business and triumphed, against all odds. In his aura I felt an undeniable sense of purpose and steely resolve. This man wouldn’t tolerate fools. He was, after all, the King.

The focus of our conversation was the then-new recording of Riding with the King, his Grammy-winning collaboration with Clapton. But in addition to specifics about this fiery album, King shared powerful insights about his music, the blues, and other guitarists.

“I feel that I’m quite limited,” he told me as he gazed across his sparkling new club, with carpenters, television camera crews, bartenders, and wait staff scurrying around to get ready for the grand opening that was only hours away. “But I tease Eric. I told him he’s like my lady—he can get me to do things I’d never do. Like doing acoustic things? Ain’t no way I would have pulled it out. But he suggested it, and I tried it, and it worked out all right.”

King didn’t like to boast about his guitar playing. “I never practice as much as I should. And it’s laziness on my part, so I’m nothing like as good as I should be. While it always sounds good to me, it seems to me that I’m pleasing myself, not other people. And I want everybody to be able to get something good out of what I do. But then I’m lazy, and I find myself getting angry with me about that. But I know whose fault it is—mine.”

He went on to recount a story from the ’60s that occurred at the historic Cafe au Go Go in New York. “One night during this time, we had a jam. Al Kooper from Blood, Sweat & Tears, he was with us. Jimi Hendrix was with us. I remember Jimi Hendrix tape-recording what we were doing that night. And he was supposed to give us a tape. And he died before I got my tape. So I keep saying now, when I die, now if I can find him, he’s going to give me my tape! Because that was a memorable occasion.”

The conversation shifted to another deceased guitarist, Stevie Ray Vaughan. “He was like a son. I’ve got four sons—and I love them all—but it seems like he was the fifth one. That’s the way it was with Stevie. Stevie had a way of respecting me, and when he smiled, it would just go through me. He was a beautiful young man. God, I miss him.”

When I asked King to describe what he listens for in other guitarists, he didn’t mince words. “I like for them to put themselves into what they’re doing. Not just play. Not just be technical. I’m not so much so, but a lot of people are so technical that everything they play is so right there, so to the point. That’s good. It shows that you practice. But when a guy lives what he’s doing, you can feel it.

“I guess if I could play fast I wouldn’t want to be as fast as a lot of the people are. If you notice, my talk is slow. That’s the way I feel when I’m playing. I want to make sure you understand every word. Trying to get my point over. Stammers and stutters, I do a lot of that. I think that’s even in my playing. So I sometimes have to go back and get that note again and try to make sure that it’s clear and to the point this time. So you get me. You understand? That’s the way I hear myself playing.”

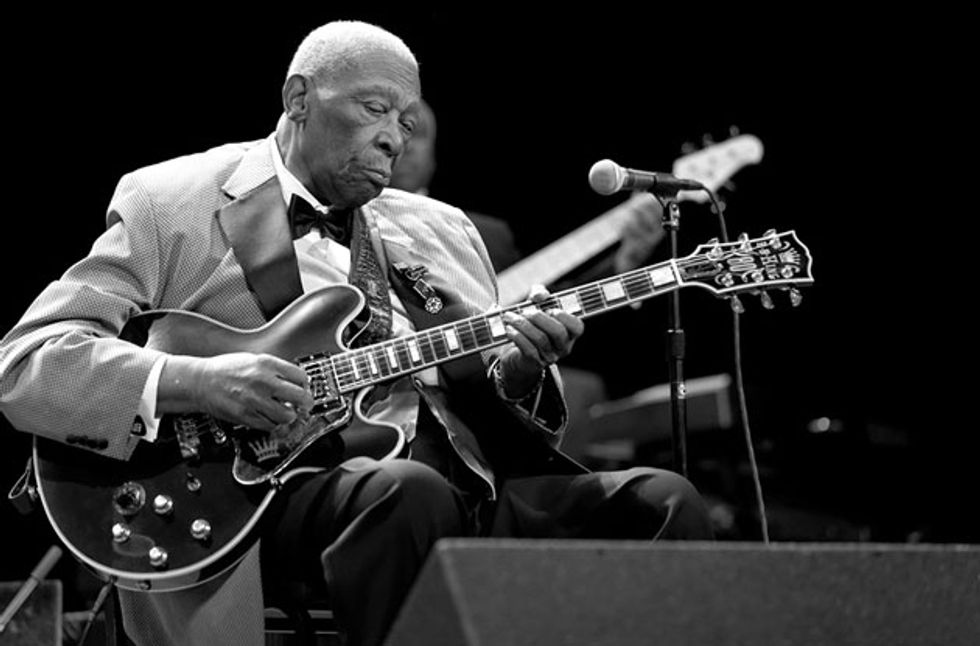

Photo by Ken Settle.

And King’s heroes? “Some of the people that I listened to in the early years, T-Bone Walker, Elmore James, Lonnie Johnson, Blind Lemon [Jefferson] ... and you gotta remember Django and Charlie Christian. They were jazz guitarists, and I loved them. But Lonnie Johnson was at the top of the heap for me.

“Another idol I never talked a lot about—this might be the first time I ever mentioned it—Louis Armstrong. Louis had the gravel voice, but he was so much better than I’ll ever be because he knew all the standard tunes. He was a great jazz musician, but he played blues like nobody else. I felt what he was doing. I believe you are the first person I’ve ever mentioned that to.”

Even as King’s manager and publicist began hovering around the table—our time would soon be up—he had words of wisdom to share with fellow guitarists and he wasn’t going to be rushed. “I thought that everybody seemed to get a break but me, in the early years. But I wasn’t bitter about it because I figured they got a break because they deserved it. But I thought I did too, at times. And finally—finally—when a lot of the kids started to play, and a lot of them were playing blues, they opened up a lot of doors for B.B. King. And I pray on it sometimes, and I say, ‘Thank God, better late than never.’ But I was never bitter. I don’t feel I have a right to be bitter. You can’t make people love you. They love you if they want. So it’s the same thing about your playing. If you do it and do it well, somebody’s going to appreciate it. Keep at it. People will appreciate it.”

And Mr. King, we do appreciate your playing, singing, and your spirit. Many thousands of us love you, and your music will endure as long as there are guitarists on planet Earth playing the blues. You are the King of the Blues—yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.