Most of us have a crystal-clear picture imprinted in our psyches—a stark moment of when our younger, more impressionable selves first heard a recording that blew our minds, and from that point forward, everything would be different. In those moments of discovery, turned obsession, worship, and deep learning, a bold appreciation and respect emerges for someone else’s expression. It’s the personal joy of experiencing art that moves you. In a human existence riddled with many uncertainties, inspiration is something to hold onto. The possibilities are endless with music, and the journey never ends. We hope you enjoy going down memory lane.

Photo by Ali Hasbach

Photo by Ali HasbachJennifer Batten (Michael Jackson, Jeff Beck)

Jeff Beck — Blow by Blow and Wired (1975; 1976)

I first heard tunes from Blow by Blow on mainstream radio when I was a teen. Jeff Beck opened up my ears to advanced sounds, styles, and textures. A Guitar Institute of Technology (GIT) classmate, Steve Lynch (Autograph) played “Cause We’ve Ended as Lovers” for a performance assignment we all had, which really affected me. Afterward, I became obsessed with learning every solo on both records. I absorbed volumes from dissecting and emulating those like a mad scientist, learning subtle details: bending nuances, rude noises and odd harmonics, the sweetness of his vibrato, and phrasing.

Dave Cobb

Led Zeppelin — Led Zeppelin (1969)

Led Zeppelin is the best rock ’n’ roll record of all time. It’s the best sounding as well. They were just starting the band and were really excited, and you can hear that in the recording. As a guitar player, I was obsessed with Jimmy Page’s tone. He had the fuzz … and how he would roll back the fuzz for that clean chimey sound. It was a bombastic sound, and then it could get so intimate. You’d get drawn toward it, but—boom—it’s right in your face when Page hits a solo. That album defined the rock ’n’ roll spirit. Probably half the things I do are ripping him off. My guitar playing became a poor man’s imitation. He was such a pioneer for so many aspects of the studio as well. That also influenced me in producing records.

Photo by Don Van Cleave

Photo by Don Van CleaveLuther Dickinson (North Mississippi Allstars, the Word)

Various Artists — Sacred Steel (1997)

The first sacred-steel compilation released on Arhoolie Records unquestionably changed my life. This form of gospel music had been obscured for decades, and it inspired John Medeski and me to start an instrumental band called the Word. Then we befriended Robert Randolph—who had grown up playing in that tradition—and he joined the Word. Robert taught me so much about gospel melody and gospel rhythm guitar playing. Aubrey Ghent, the grandson of the founder of sacred steel, became a great friend. Roosevelt Collier is another great friend and sacred-steel hero of my generation. Of course, there’s Electric Ladyland by Jimi Hendrix and At Fillmore East by the Allman Brothers, and there’s Mississippi John Hurt and Mississippi Fred McDowell. They all changed my life, but sacred steel brought so many new friends of that tradition into my life, and for that I will always be grateful. It also reinforced this idea I have that certain harmonies and rhythms are inherent in nature, and they’re going to come out in different cultures, unbeknownst to each other. If you listen to the early sacred steel, it sounds like the Allman Brothers, but these musicians had never heard of the Allmans. I think that’s pretty fascinating.

Photo by Chapman Baehler

Photo by Chapman BaehlerDavid Ellefson (Megadeth)

Judas Priest — Unleashed in the East (1979)

When I saw this album, it made me want to go be a rock star. Seeing K.K. Downing with his long blond hair and Flying V in the air, and the double-bass drums … and I’d never seen a singer look anything like Rob Halford did on that cover. Leather, lights, fog—everybody had long hair. Up until this point I’d heard a lot of hard rock, but this was the first truly heavy metal record I’d heard. And a big part of it was that everybody shined: The guitar work was incredible, the vocals were incredible—to hear screaming like that was unworldly. There was a component about it that sounded so heavy and so violent that it actually scared me.

Photo by Kan Lailey

Photo by Kan LaileyReeves Gabrels (The Cure, David Bowie, Tin Machine)

Lou Reed — Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal (1974)

I had Layla, The Allman Brothers Band, and Humble Pie, but the thing about Humble Pie was like the thing about the Black Crowes. I didn’t really believe that was the life of the singer. The thing about Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal … the guitar playing on that was set pieces—like what Ronson did with Bowie. Steve Hunter and Dick Wagner had orchestrated parts, but parts of the song were also free. It was poetic, like Erik Satie, Debussy, or even Bach. The music was heavy. And most importantly, it wasn’t somebody living a fantasy or telling made-up stories. It was Lou Reed. He did those things. It was as real as John Lee Hooker, and that spoke to me in a big way. In 1974, my father died in a car accident and my whole world imploded. I needed a voice, and it turned out to be Lou Reed’s. Eight months later I was living in New York and going to art school, and I wanted to serve real-life songs in a scenario like that. Hunter and Wagner are on a par with or superior to anyone else in rock.

Donna Grantis (Prince, 3rdEyeGirl)

Miles Davis — Big Fun (1974)

This album has not only a strong vibe, but imagination and improvisational creativity. It also was a gateway for discovering a plethora of amazing albums by Miles during his early-’70s “electric” period that featured rockin’ guitarists. I love the extended grooves that combine a jazz sensibility with electric guitar wizardry—notably Pete Cosey’s wah-infused solos on Dark Magus, and John McLaughlin’s stunning playing on In a Silent Way. While the music can be very meditative at times, there’s also an edge and attitude. It sounds fresh every time I hear it and is a big inspiration for my upcoming album. Thanks to my mentor and bandmate Prince for introducing me to this record.

Photo by Danny Clinch

Photo by Danny ClinchBen Harper

David Lindley — El Rayo X (1981)

This is Lindley’s first solo record after playing with Jackson Browne. A masterpiece. This record is a genre. It’s untouchable. Just stop. Put it down. Go home. Practice. Me. You. All of us. This is the record where the 6-string electric lap-steel guitar broke through the earth’s atmosphere, escaping the gravitational pull from where the instrument was. As a kid, I saw this record played live numerous times. It was insane and the record sounds fresher every time I play it.

Warren Haynes (Gov’t Mule)

Allman Brothers Band — At Fillmore East (1971)

I heard the Allman Brothers for the first time in 1969 when I was 9. I had two older brothers who exposed me to new music. By the time Fillmore East came out in ’71, I’d started to pick up guitar. I grew up in North Carolina, and every guitar player in the South latched on and connected to that music. My friends and I listened to it on a loop, on an 8-track. There were these long jams that were unlike anything I’d heard before. It’s much more valuable to study the construction of a 2-minute solo than to study a 10-second solo. That music was part of my DNA. If I hear another live version of one of those songs even from a similar time period, I instantly can tell it’s not the one I grew up with. When you hear something a hundred times, it just has a way of seeping into your soul. Fast-forward: Who knew I’d have the opportunity to join Dickey Betts’ band and then the Allman Brothers Band at age 28? At the first rehearsal, suddenly these songs I grew up playing had this majestic quality that only the Allman Brothers are capable of presenting. It was an amazing, overwhelming feeling.

Henry Kaiser

Evan Parker, Derek Bailey, Han Bennink — The Topography of the Lungs (1970)

In 1971, I bought a copy of this LP and it was one of my primary inspirations to pick up guitar. I’d previously been fascinated by musics where improvisation was the main thing going on: Indian music, free jazz, the Grateful Dead, to name just three examples. The music on Topography obviously contained more improvisation per cubic hyper-second than anything I’d heard before. It also featured three players who were masters of creativity and personal expression. Hearing them brightly illuminated a path that I have followed for the past 45 years.

Photo by Paul Janovitz

Photo by Paul JanovitzBill Janovitz (Buffalo Tom)

Talking Heads — Remain in Light (1980)

Though I was already into the Talking Heads at the time, my mind felt like it was cracked open when I played the new Remain in Light up in my bedroom after receiving it from my uncle and his boyfriend for my 14th birthday. As a burgeoning young guitar player, exposure to guitar solos that were the most innovative sounds since Hendrix blew my head off. Against the band’s relentlessly pulsing, polyrhythmic loops, their sideman Adrian Belew made his Strat sound variously like a horny rhino or some sort of epileptic robot having a seizure. There are perfectly syncopated bits of pixilated feedback that sound like an AOL dial-up modem or fax machine years before most of us had any concept of what those would be like. And there are some of the slinkiest, most sensual sounds wrested out of a Strat since Jimi. The sick solo on “The Great Curve” has to rank in anyone’s Top 10.

Photo by Piper Ferguson

Photo by Piper FergusonJohn Jorgenson

Yes — Fragile (1971)

I was 15 and had been playing guitar and bass for a few years when this masterpiece from prog-masters Yes was released. I’d heard “Roundabout” on the radio and was instantly knocked out by all the elements of that classic Yes lineup—soaring vocals, virtuosic keyboards, complex yet taut drumming, a totally new bass-guitar style, and guitar parts and tones that seemed to cover multiple fingerboards! The rest of the songs were equally good, and Steve Howe kept me interested, amazed, and inspired. I learned so much from this album, not only technically and musically, but conceptually, too. Having grown up in a classical music family but loving rock at the same time, here was a band who combined aspects of both and created something quite progressive—when “prog” wasn’t even used yet to describe a musical style.

Photo by Kelsey Reckling

Photo by Kelsey RecklingWilliam Keegan (Together Pangea)

Modest Mouse — This Is a Long Drive for Someone with Nothing to Think About (1996)

The album that really changed my life was Modest Mouse’s This Is a Long Drive for Someone with Nothing to Think About. I was probably 12 when I first heard it. At that time, I’d only heard whatever [L.A. alt-rock station] KROQ or MTV was playing. Modest Mouse was kind of revolutionary to me—they sounded so different from all the corporate rock stuff. Isaac Brock’s guitar playing and voice were kind of grating but full of feeling, and the lo-fi production gave it this otherworldly quality. The first song I listened to was “Talking Shit About a Pretty Sunset,” and the first guitar solo I ever played along with over and over again until I got it right was from “Dramamine.” The album opened my eyes to the wonderful world of music that isn’t radio friendly, and I will be eternally grateful for that.

Photo by Simone Cecchetti

Photo by Simone CecchettiKaki King

Lush — Split (1994)

I was 14 when I first visited NYC in the ’90s, and the only thing I really wanted to do was visit the gigantic HMV record store in Times Square. It was there I bought the album Split by the British shoegaze band Lush. I spent the next week wandering the city that was to eventually become my home with my ears awash in gorgeous reverb, harmonious delays, mysterious lyrics sung in falsetto, majestic string arrangements, and unexpected bass lines. There wasn’t a single song I ever skipped. Start to finish, it was the perfect album for me—a shy, closeted, embarrassed teen who had no real idea how to function in the world of people, but who could be carried away for days in a cloud of delay pedals and dreams.

Julian Lage

Bill Evans and Jim Hall — Undercurrent (1962)

I ended up with a copy in my mom’s car and my dad’s car. For maybe three or four years straight that was all we played in the car. I didn’t realize how much I loved it until I started making music on my own. One of the first times Jim and I hung out, I asked him if they had toured together and what the precedent was for that record date. He said there wasn’t any touring, just maybe a show at the Vanguard. At one point, I asked him about what he was thinking when playing rhythm guitar behind Bill and he said something like, “Boom, boom, boom, boom.” I laughed nervously, but he was serious. His approach was that if you think that, your hand will carry it out. That album is the blueprint for tone, interaction, balance of humor with virtuosity—everything is there.

Photo by Jimmy Hubbard

Photo by Jimmy HubbardLuc Lemay (Gorguts)

Death — Scream Bloody Gore (1987)

I remember when I heard Death’s first album, Scream Bloody Gore, for the first time—it was unbelievably fascinating. I was maybe 15 or 16 years old, and I couldn’t believe how heavy every single tone on the record was. From vocals to guitars ... man! That’s when I decided to buy my first electric guitar. I wanted to sound like Chuck [Schuldiner]. I wanted to be a guitarist and vocalist like Chuck. And, 30 years later, the love and passion for death metal is still there.

Photo by Robert Juckett

Photo by Robert JuckettTony Levin (Stick Men, King Crimson, Peter Gabriel)

Oscar Pettiford — Oscar Pettiford (1954)

To me, “life-changing album” means the one with the most impact on my sense of music. Way back in the 1950s, my brother Pete and I came across Oscar Pettiford’s self-named album [a 10-inch LP on Bethlehem Records]. It had the great Julius Watkins on French horn (Pete’s instrument at the time), Charlie Rouse on sax, and on bass, Oscar’s incomparable playing (and on cello as well). As youngsters will do, we inhaled that music. We listened over and over, got all the other albums with the same players, and so the music became, subliminally, part of our musical mind. Whether I was to play jazz or rock, that album informed my future music. The purity of groove, choice of notes, excellent composition, and overall musicality set me on a great path to try to make music of my own.

Photo by Levi Walton

Photo by Levi WaltonJ Mascis (Dinosaur Jr.)

The Stooges — The Stooges (1969)

I had the album when I was a kid, but didn’t start playing guitar until I was 17 after the hardcore band I played drums in broke up. I wanted to start a new band playing guitar, so I bought a Jazzmaster, bought a Big Muff, and just learned how to play. I thought Ron Asheton had the best guitar sound, so it was the guitar sound I was trying to go for. His playing didn’t seem so hard, so it was doable for me to play the songs—unlike Hendrix or something where I had no idea what was going on and it was impossible to figure out. It’s still my ultimate, recorded-guitar sound and still my ultimate guitar tone to achieve.

Photo by Fumie Ishii

Photo by Fumie IshiiGlenn Mercer (The Feelies)

The Beatles — Meet the Beatles (1964)

Meet the Beatles was the start of my interest in rock ’n’ roll. Shortly after seeing the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show, my mother bought the record for my brothers and me. A lot of energy came through the speakers. And you could tell that, even in the studio, they were playing live and having fun. Most records had a certain level of polish. That record didn’t. I wasn’t playing an instrument at the time—I was 9—but got very analytical about it, picking out who was doing what. Shortly after hearing it, I persuaded my brothers to play “Beatles” with me. I made cardboard cutout guitars and told them, “If we’re gonna do this, you have to know what parts they’re doing.” I learned about harmony, arrangements, choruses, and all kinds of things from that album and their second one, even though I didn’t know what those things were called at the time.

Photo by Chapman Baehler

Photo by Chapman BaehlerDave Mustaine (Megadeth)

AC/DC — Let There Be Rock (1977)

I got the record because of the album cover, but when I put it on it was clear to me that AC/DC was going to be one of my favorite bands. There was no comparison—the sound of the amps, the sounds of the progressions … picking the blues-style rock ’n’ roll and really pushing it to the extremes. And Bon [Scott, original AC/DC vocalist] was the icing on the cake. Angus’ style was simple in its approach but it was so raw. I was, like, “Wow, this is what I wanna be.”

Rick Nielsen (Cheap Trick)

Jimi Hendrix — Are You Experienced (1967)

At first I had the single of “Hey Joe” that my mother got for me when she was in Germany, and then I got the English version of Are You Experienced, with the shiny cover. Jimi was just so far ahead of everybody else—tone-wise, show-wise, song-wise, production-wise. It was the phrasing … these weren’t pop songs—this was heavy-duty stuff. He was so far ahead of the game in so many ways that it’s hard to explain. He was the whole package.

Photo by Josh Giroux

Photo by Josh GirouxRobin Nolan

The Rosenberg Trio — Seresta (1989)

I first heard this album in 1990 and it totally changed my life. It was at the Django Reinhardt festival in Samois, France, where I saw Gypsies (Django’s people) killing it on guitars outside their caravans. Under the stars with campfires, wine, exotic girls … it was all too much. This album made me put down my Les Paul and pick up a Gypsy guitar, move to Amsterdam, and devote my life to Django’s music. The Rosenberg Trio’s debut album Seresta captures the spirit of those times for me and the raw energy and virtuosity of Stochelo Rosenberg’s playing is just as mind-blowing today as it was then!

Photo by Tyler Zoller

Photo by Tyler ZollerRev. Josh Peyton, (Rev. Peyton’s Big Damn Band)

Charley Patton — Charley Patton: Founder of the Delta Blues (1971)

When I was a kid first learning the guitar, I gravitated toward blues. It pulled me like a magnet to iron. I became obsessed with its roots. Charley Patton was the man who inspired Muddy and the Wolf to pick up a guitar. After I first heard Charley Patton: Founder of the Delta Blues, the Yazoo release, my life was never the same. The slide is otherworldly. It’s like there are two guitar players, with his right thumb keeping time. His voice is still possibly the biggest to ever be recorded. I’ve been a disciple of Charley Patton ever since.

Photo by Sobieslaw Pawlikowscy

Photo by Sobieslaw PawlikowscyAlex Skolnick (Testament, Alex Skolnick Trio)

Van Halen — Van Halen (1978)

As a preteen, hearing Van Halen marked my shift from guitar hobbyist to aspiring pro, from budding enthusiast to serious musician. Bolstered by a mad scientist’s mind for mechanics, EVH’s unorthodox approach to guitar playing and gear modification sent millions to practice rooms and caused manufacturers to rethink their product lines. Van Halen remains a Mount Everest of guitar, with a zenith entitled “Eruption,” featuring two-handed skills so unique that they overshadowed EVH’s equally astonishing phrasing, bluesy feel, and rhythmic swing. The album’s additional references to heat—fire, atomic energy, the Devil—with the cooling relief of “Ice Cream Man,” are all symbolic of its searing guitar sound, achieved by literally sizzling the amplifier’s power tubes.

Photo by Patrick Shipstad

Photo by Patrick ShipstadSteve Stevens (Billy Idol)

Yes — Close to the Edge (1972)

I was 13 years old when this milestone was released. I’d already been introduced to guitarist Steve Howe via the Fragile album. Steve encompassed everything I’d learned on my instrument—ragtime, jazz, psychedelic—and had a blistering alternate-picking technique. With Howe, I could hear every note clearly and his phrasing was inviting, somewhat playful. It was Chris Squire’s bass sound that occupied the role of distortion and aggression. With Close to the Edge, Yes created a masterful journey that, with my headphones on, took me far away from suburban life, far away from school, far away to a world I wanted to be part of—creating expansive music to fill arenas with.

Andy Summers (The Police)

Wes Montgomery — The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery (1960)

I was playing with a quartet when I was about 16 and one night in particular I managed to get through the whole fucking solo of “West Coast Blues” [laughs]. Those beautiful minor 7 licks that he played flawlessly across the bar really made an impression. That album was where I really connected to jazz. Wes’ playing was a bit mysterious to me at the time when I was learning the language, but I got into it. It’s absolutely amazing to realize that he wasn’t an “educated” musician and he didn’t go to school to learn what notes to play over what chords. It was a combination of a phenomenal ear and an incredible thumb.

Gemma Thompson (Savages)

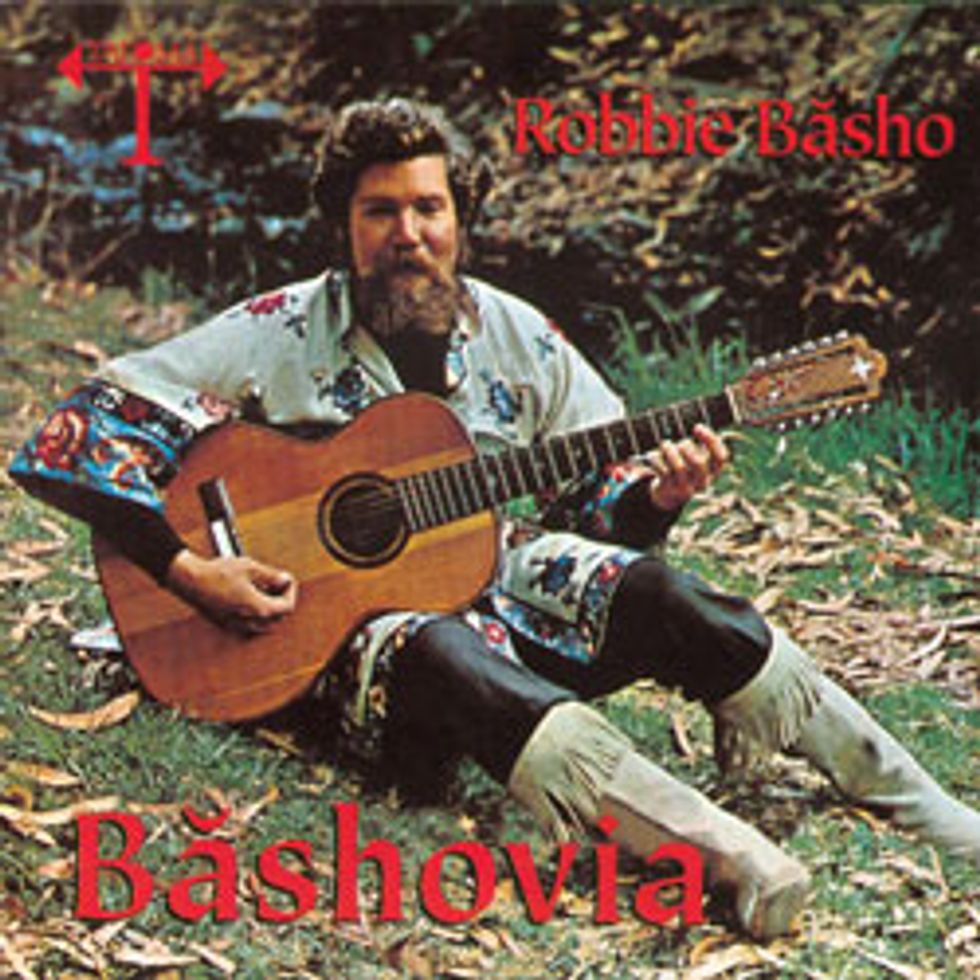

Robbie Basho — Bashovia (2001)

Robbie Basho’s Bashovia caught me off guard when I first listened to it, as I hadn’t heard anything like it. I wanted to know everything about this musician and how an acoustic guitar could describe a journey across a landscape, how an instrument could be so visual. His use of other tunings and interest in Indian classical music (learning to play the sarod, for instance) led his approach to the guitar to be like no other. Most of the tracks on this compilation are instrumental, but when he does sing, it’s enigmatic and strange, yet totally beautiful. (The song “Blue Crystal Fire” is also a favorite, though not on this album.) I find it so heartening that one instrument can convey so much because the musician believes it can.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)