Fortunately for Umphrey’s McGee fans, Brendan Bayliss is not easily deterred.

When the guitarist, singer, and founding member of the band tried to get into the University of Notre Dame’s music program, the program’s director was less than enthusiastic. As Bayliss recalls, these were the director’s words: “You can’t read music. You have no formal training. What you’re trying to do is like me trying out for the Cincinnati Reds. You’ll never have a career in music. Go somewhere else.”

This year marks the 20th anniversary of Umphrey’s McGee—one of the top-drawing acts on the thriving jam-band circuit, with 11 studio albums and more than 2,200 shows under their belt—and it’s apparent Bayliss was wise to take those words with a grain of salt. Along his self-styled path to musical enlightenment, Bayliss sought out lessons from one of the top guitarists in the South Bend, Indiana, area: Jake Cinninger. Little did he know that Cinninger would join Umphrey’s ranks two-and-a-half years later.

Bayliss and Cinninger have coalesced into an impressive dual-guitar team, and—with the help of bassist Ryan Stasik, drummer Kris Myers, percussionist Andy Farag, and keyboardist Joel Cummins—they interweave myriad sonic ingredients into a genre-defying stew that’s still evolving. In fact, though the term “jam band” might be accurate to describe their milieu, audience, and penchant for improvisation, it doesn’t fully capture the band’s essence. Elements of prog, blues, jazz, funk and math rock—even heavy metal—inform Umphrey’s McGee’s sound. And though they’re willing to let things get pretty chaotic as they explore the outer edges of improvisatory mayhem, for the most part, there’s a lot more precision involved in their music than the term “jam band” typically connotes.

The band’s voracious appetite for a wide variety of styles is evident on their latest album, it’s not us. “It represents the band, because it basically runs the gamut from prog-rock to dance,” Bayliss says in the press release. “We’ve mastered our ADD here. The record really shows that.”

Lead track “The Silent Type” is a catchy, concise, radio-friendly rocker, with Bayliss delivering a cautionary tale about poor decision-making. “Looks,” a Cinninger tune, starts out with a heavy funk-rock groove, but ventures into proggier territory courtesy of Cummins’ vintage-sounding synth interlude and Cinninger’s dissonant, angular solo. “Whistle Kids” is Bayliss’ ode to the joys of negotiating fatherhood with a hangover, and it features a delightful laid-back groove and some of Cinninger’s tastiest guitar work on the album. (Cinninger handles most of the lead guitar work in the band, though Bayliss is a fine instrumentalist himself.)

Things start to venture into the prog/math-rock world on the odd-meter “Maybe Someday,” with Cinninger channeling his inner Eddie Van Halen near the song’s end. The band’s tendency to indulge a hodgepodge of influences is most evident on “Remind Me,” which starts off as a funky roots-rocker before taking a series of left turns: first to a frenzy of feedback and noise, then to a metal-style freak-out featuring double-bass-drum-pedal propulsion and searing guitarmonies.

Other highlights include the sweet acoustic ballad “You & You Alone,” a love song Bayliss wrote for his wife; the jazz-funk workout “Speak Up,” featuring legendary jazz saxophonist Joshua Redman, who frequently sits in with the band; and “Dark Brush,” in which Cinninger gets to fully indulge his metal tendencies.

TIDBIT: Bayliss says that Umphrey’s McGee’s new album, the group’s 11th studio recording, “Represents the band, because it basically runs the gamut from prog-rock to dance. We’ve mastered our ADD here.”

Premier Guitar recently spoke with Bayliss and Cinninger, who discussed the new album, their unique approach to improvisation, and their cutting-edge methods for enriching the audience experience.

The lead track of the new album, “The Silent Type,” is a solid, concise radio-rock tune. It’s three-and-a-half minutes, no jam—not necessarily what people expect from Umphrey’s McGee.

Brendan Bayliss: It’s kind of an introduction. If you haven’t heard us, this is right down the middle.

There’ a cool octave part on that song.

Bayliss: I’m doing a clean octave with a delay. I’m doing one on the left side. And then the one on the right is behind it by one or two beats. So it sounds kind of like a delay effect, but it’s really just two separate parts, split.

Jake, on the solo toward the end of “Looks,” it almost reminds me of Mahavishnu Orchestra-era John McLaughlin. Lots of dissonance and chromaticism.

Jake Cinninger: Yep. There was a lot of angular triad stuff. Sort of that Adrian Belew atonal quality. I just love Adrian’s playing. He’s a good buddy of ours and has toured with us quite a few times, and he’s done quite a few sit-ins with us.

I really like your playing on “Whistle Kids,” too. That’s some of my favorite guitar on the album, because I love that laid-back behind-the-beat feel.

Cinninger: It’s the New Orleans swamp guitar kind of vibe. What I’m doing is plucking almost behind the bridge pickup really hard, to get all that tension on the note, which is almost a Dick Dale thing. And then playing really behind the beat, so the notes are dripping behind the drums.

Cinninger goes for keening high notes with a glass slide on his G&L Comanche. Note the distinctive split Z-Coil pickups. The model also has passive treble and bass controls, and allows playing with all three pickups or a bridge and neck combination, too. It is Leo Fender’s final bolt-on design.

The intro guitar riff on “Half-Delayed” is really hypnotic.

Bayliss: That’s me. I’d just gotten a new effects processor and was skimming through, and I was playing a simple line because I wanted to hear what the delay felt like, and after about 30 seconds I realized I was just playing it over and over again. It was becoming addictive, so I thought, “Okay, that’s got to be a line.”

What pedal was that?

Bayliss: It’s the Eventide H9. Our bass player has two of them. I only have one. I want to get another one, just because I want one at home so I can work on more presets. Maybe when this article comes out, they’ll read about it and send me another one! [Laughs.]

That riff makes me think of U2’s the Edge meets Afrobeat.

Bayliss: Actually, that unit has a preset called … it’s not the Edge, but “Where the Streets Have No Name” or something like that. [Editor’s note: It’s called “Streets.”] I use it live, with a tap tempo. It’s awesome.

Do you wind up tweaking a lot of the algorithms on the H9?

Bayliss: I go into them and tweak because I don’t like volume changes. I want everything to be level.

“Remind Me” is interesting. It’s a completely nontraditional song structure. It’s almost like a suite.

Cinninger: We cut a lot of that live with the drums, too.

Jake Cinninger

So the solos at the end are live? That’s impressive. Makes me think of a metal version of Yes’ “Heart of the Sunrise.”

Cinninger: Yeah. We went into that sort of cacophonous thing—that sort of Mastodon ending. All those guitar solos were first takes.

“Dark Brush” also has a major metal vibe.

Cinninger: It’s a little more of a newer metal vibe. Like Nine Inch Nails meets Mastodon, and Deftones—a jam band doing nu metal. Let’s throw that in the mix and see what happens.

Who were some of your big guitar influences?

Bayliss: The first time I ever played a guitar, it was my older brother’s. When I started playing, he turned me on to Stanley Jordan. That was my first jaw dropping, “Okay, wow!” Before that I was always into the Beatles. And right when I got to high school, when I was 14, I started listening to Led Zeppelin. And, basically, for the next couple of years it was Jimmy Page. Jimmy Page probably taught me more than any single guy. Obviously, you get the blues, but you also get the acoustic stuff, the open tuning stuff, the slide guitar stuff. And then he does his own thing that you can’t really categorize. And I still geek out on Slash. It’s a function of, right when they came out I was just starting to get into trouble, and I thought that Guns N’ Roses were the coolest. When I met Jake, he turned me on to Al Di Meola. Jake let me borrow this VHS tape—it was basically the Al Di Meola “how to be awesome” video. And I burned through that thing for, like, two months, every single day.

Guitars

G&L Comanche

G&L S-500

Gibson Frank Zappa “Roxy” SG

Harvey Guitars 7-string

Babicz acoustic

Amps

Fuchs ODS 100

Schroeder custom amp

Oldfield JC-100

Effects

Source Audio Soundblox 2 Orbital Modulator

BBE Mind Bender Vibrato/Chorus

Banzai Cold Fusion Overdrive

Malekko Omicron Series Analog Fuzz

Fuchs Royal Plush Compressor

Morley Steve Vai Bad Horsie Wah

Radial Engineering Tonebone Classic Tube Distortion

Marion Henry Electric Fuzz Bucket

Moogerfooger MF-104M Analog Delay

Boss PS-5 Super Shifter

Boss PH-3 Phase Shifter

Guyatone MD2 Micro Digital Delay

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL110-10P (electric, .010–.046)

D’Addario EXP26 (acoustic, 011–.052)

Telefunken Elektroakustik Thick Diamond TFUNK 2 mm picks

Cinninger: The first one that hit me the hardest was obviously Frank Zappa. And that was early on. That’s what my parents were spinning. A lot of Genesis: Mike Rutherford and Steve Hackett. And John Lee Hooker was always playing in the house. And, when I started to see shows, people like Todd Rundgren. I remember seeing Randy Rhoads before he passed away. That one really freaked me out. I was, like, 7 years old at the time. There were KISS influences early on. Then I started getting more seriously into the classical guitar world, and took nine years of classical guitar. I ended up going to Southwestern Michigan College for a bit, and I ended up getting harvested for a country project really quickly. I ended up heading to Nashville and trying to make a good name with this country band. You know how that goes. And then I started a band called Ali Baba’s Tahini, and that started that whole foray of trying to mix all those styles into one bag—trying to make it work, all the influences and records I’d listened to up until that point.

How did your paths cross?

Bayliss: Umphrey’s McGee started in ’98, and then Jake joined about two-and-a-half years later. We were in South Bend, he was in Ali Baba’s Tahini, and I went up to his house to get guitar lessons from him, because he was the guy—the best guitar player in the region. I basically went up there with a handheld recorder and said, “Show me everything you can, and I’m going to record it and work on it.” Which is kind of bizarre, because two-and-a-half years later, we’re in a band together and I’m doing things he showed me how to do.

Cinninger: Brendan was kind of a folk-based singer-songwriter. And then all of a sudden, the wave of the jam-band world was really happening, and we were like, “We could possibly do this thing together.” Because he really picked up everything extremely fast, I knew right away Brendan had something really special. He could imitate anything I threw at him. That was the key moment where we thought, “Hey, this could really work as a dual-guitar scenario.”

Umphrey’s McGee clearly exists within the jam-band world, yet you are very different than most of the major groups in that scene, which typically have more obvious threads of bluegrass, folk, and roots-rock in their DNA. Were you ever into the Dead, Phish, Widespread Panic, and the like?

Bayliss: I went through a Phish phase, for sure. I saw them in 1993 in Indianapolis, and I remember leaving the show thinking to myself, “I want to go see that again.” Because it was all over the place. They had bluegrass, jazz, they played an AC/DC cover. I dug Jerry Garcia, too.

Cinninger: Oh yeah. I’m a huge Jerry Garcia Band fan, Grateful Dead fan. Love Widespread, always have. Phish, I only saw them once back in the day. But then you have to look at, if you’re super-influenced by someone like Trey [Anastasio] when you’re in my sort of position, it’s kind of the kiss of death. You have to be careful with what you’re influenced by, and how big that guitar player is in our world. I’d rather, say, be influenced by Roy Buchanan, and use some of those tools that influenced people like Trey and Jerry. I’ll think, “Where did those guys get their bags from?” Danny Gatton, Rory Gallagher, Thin Lizzy—there’s like this huge bed of lost guitar greats.

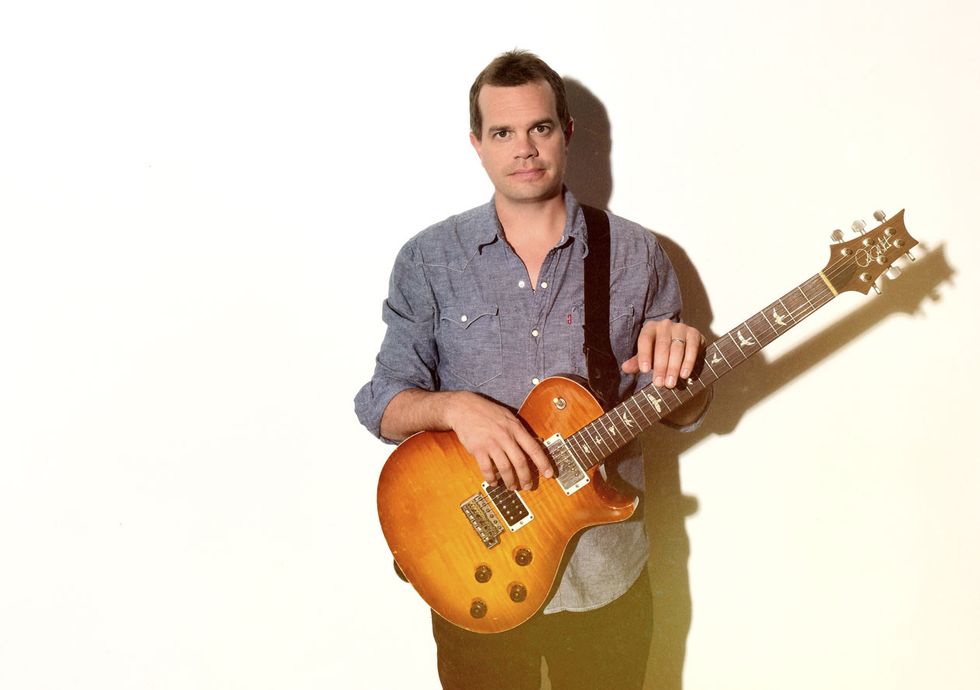

Bayliss’ electric workhorses are the Paul Reed Smith Singlecut in this photo and a PRS SE Mark Tremonti Custom. Jimmy Page, Stanley Jordan, Slash, and Al Di Meola are among his earliest influences.

Unlike most groups in the jam-band sphere, Umphrey’s McGee has a strong metal influence. Where does that come from?

Bayliss: Jake was a drummer in a metal band when he was, like, 12 years old. He was into metal before I was even playing guitar.

Cinninger: It started early. Eddie [Van Halen] and Randy [Rhoads] were the first things that were dropping on vinyl when I was 6, 7, 8 years old. It was just tearing my head off, kind of freaking me out. And then that carried into the classical. I would stay up until midnight waiting for Headbangers Ball to come on, and that was sort of like your heavy metal culture. Obviously, there was no Internet back then, no info coming your way until you stayed up and watched all the latest metal videos. The early Megadeth stuff killed me, with Chris Poland, who’s one of the top dogs in the that whole metal guitar world. And I got to do a couple albums with him later, with a band called OHMphrey—a couple guys from Umphrey’s, and then we got a couple of his guys—out in Los Angeles a couple years back. And Alex Skolnick from Testament, the Slayer guys, Anthrax, obviously, Metallica. All the big dogs were very present in my listening catalog at that time.

There’s also a notable prog-rock vibe in your music. There’s a lot of dissonance, complexity, chromaticism, and odd-meter math-rock stuff going on.

Bayliss: Zappa started everything for me. Then I got into Mahavishnu Orchestra, John McLaughlin, and all that stuff. And then Al Di Meola, that album Casino—we do [the Chick Corea composition] “Señor Mouse.” And Rush was big.

Cinninger: Growing up, I was really freaked out by Emerson, Lake & Palmer. I was flabbergasted by the sound that was coming out of their records. Especially at a young age, it was like alien space-prog for me. And obviously, Robert Fripp and King Crimson, with Starless and Bible Black and Red, and later on, Discipline. It just freaked me out what he was able to do, while keeping it fresh. When you look at the idea of what a jam band is in America, and what jam band means as far as a world term, if we were to call ourselves a prog band in America, I don't think we’d be able to get a gig. By using just the label of jam band, it’s a safe harbor for a progressive rock band.

Some prog-rock bands liked to stretch out, but improvisation isn’t quite the primary force like it is in the jam band world. With jam bands, while fans certainly enjoy hearing their favorite songs, more than anything they are coming to shows hoping to have their minds blown by the spontaneous and unexpected. They’re seeking a transcendent experience.

Cinninger: Exactly. Getting on this rocket ride, no one really knows—not even the musicians—what’s about to happen. There’s a sense of urgency, being in the moment. Cream was the first jam band, and then there was Beck, Bogert & Appice. Those guys would just fucking jam forever. And then look at even some really random off-the-wall stuff like Grobschnitt, from Germany. They had a song called "Solar Music" that was, like, 35 minutes long, German, complete space-improv rock. Even some of the Can stuff from Germany: very elongated, really cool guitar solos, space stuff. I think one big tool we used that kind of made it work for us is just not being safe with the music. Being kind of reckless, wrong notes and right notes, forcing different shifts where they shouldn’t be, in a genre. I think that was our job, to kind of ruffle feathers. Anything is possible. You just have to execute it like a professional. And then people go, “Oh, I can play flat-fives in a jam band.” And you play wrong notes, and make them into right notes, like John Coltrane would.

Guitars

PRS Singlecut

PRS SE Mark Tremonti Custom

Babicz Identity Series Dreadnought

Huss & Dalton CM

Amps

Mesa/Boogie Lone Star

Hard Truckers 2x12 cab (Electro-Voice EVM12L speakers)

Oldfield Series 64 OD Club 80 2x12 combo (four 6L6 power tubes)

Oldfield 18W Honky Tonk D’Lux (two 6L6s)

Vox AC30

Mesa/Boogie Mark IV

Effects

Stigtronics Compressor

Morley Steve Vai Bad Horsie Wah

Cusack Music Screamer Overdrive

Cusack Music Tap-A-Whirl

MXR Phase 90

Stigtronics Delay

Eventide H9

Boss DD-20 Giga Delay

Boss CE-5 Chorus Ensemble

Boss OC-3 Super Octave

Mesa/Boogie Tone Burst boost/OD

Mesa/Boogie Grid Slammer overdrive

Sarno Steel Guitar Black Box tube driver

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EXL110-10P (electric, .010–.046)

D’Addario EXP26 (acoustic, .011–.052)

Telefunken Elektroakustik Thick Diamond TFUNK 2 mm picks

If you play a wrong note, play it again so people think you meant it.

Cinninger: Exactly. It’s that real jazz mentality.

That is one nice thing about jam-band audiences: They want you to take chances. Not every audience wants that. With a lot of rock bands, fans go hoping to hear the live performance sound like the album version.

Bayliss: A lot of the improvisation thing started because when we were a college band, we didn’t have a lot of songs. So it was kind of out of necessity. Just stretch everything out and be like, “Oh, go one more time, wing it,” because we were out of tunes.

Cinninger: It’s sort of a get-out-of-jail-free card, with any stylistic thing you want to try out, for a fan base that’s willing to listen to what you have to say. And that’s what we started on, and we haven’t let that go in 20 years—keeping that creative wheel spinning in all sorts of oddball directions. Some of it will rise to the top. We have 230 original songs that we can rotate and not make ourselves bored by playing the same 20.

Do you have any favorite cover songs to play?

Bayliss: We have a cover list that’s probably 300 songs. We do “Tom Sawyer.” I love that one, just because it makes me feel like I’m 15. We also do “YYZ,” {another Rush tune] which I love. We’re kind of all over the place. We do “Africa” by Toto. The chicks love that. And we do “…And Justice for All” [by Metallica]. So then the guys love that. We try to do something for everybody.

You also do a bit of what might best be described as thematic improvising, where you insert some sort of structure or thematic idea into the mayhem. Can you tell me about that?

Bayliss: We have a couple of methods. We use hand signals, like Zappa. Signals for the keys: A, B, C, D, E, F, G. We point at our crotch for D. If I take a half step forward, it’s a half-step up. If I take two steps, it’s a whole-step up. Half step backwards is a half-step down.

So you have to be careful where you step.

Bayliss: Well, you have to make eye contact first. If I’m just stepping around, it doesn’t mean anything. I’ll stare at the band members and make it clear, “Here comes something,” and I’ll make sure everyone sees it. Because we’ve done it before where two guys saw it, and two didn’t, and it was terrible. Or it was art. [Laughs.] We also have talkback mics, so we can communicate with each other onstage, and Jake will go, “Play like a robot.” And everyone will play like a robot. There’s a cool band, Tortoise, from Chicago. So someone will say, “Tortoise,” and we’ll know, “Okay, let’s think that way.” Or “ethereal,” and we’ll think airy, and whale calls, that sort of thing.

I’ve read about some of the forward-thinking, audience-experience ideas you’ve come up with, like people being able to rent headphones to get the best mix. Can you tell me about that?

Bayliss: Kevin Browning, our manager, he’s a couple years younger. He’s always been on the cutting edge of everything. We were always talking about how, when you see a show, depending on the venue, you can’t hear right, or the person next to you is screaming, or the girl in front of you is talking on the phone. We started using in-ears with belt packs. So we thought, “Why can’t we send the in-ear mix, a front-of-house mix, to a pair of headphones?” And we did this thing called the UMBowl, where we basically played an event and made it four quarters like a football game. Each quarter was a different theme. And we had the idea of having fans text in. Someone would say, “Play a heavy metal version of a Christmas song” or “Do Tortoise.” So we’re playing and we see this screen, and this theme comes up, and we have to react to it. I think people really love that. They can kind of orchestrate the band.

“Higgins” is a staple of Umphrey’s McGee’s live repertoire. At Morrison, Colorado’s Red Rocks Amphitheatre, the band starts with a Police-esque reggae groove. Around the 3:50 mark, Jake Cinninger (on the left, in the ball cap) starts a staccato line high up the neck. Soon after, Brendan Bayliss enters the fray, and the two guitarists start interweaving lines. At the 10-minute mark, things start building to a frenzy, with Umphrey’s prog and metal DNA rising to the surface. At 12 minutes, Cinninger heads into full-shred mode, before things dissolve into a spacey psychedelic cloud. And dig the lighting rig—one of the best in the biz.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.