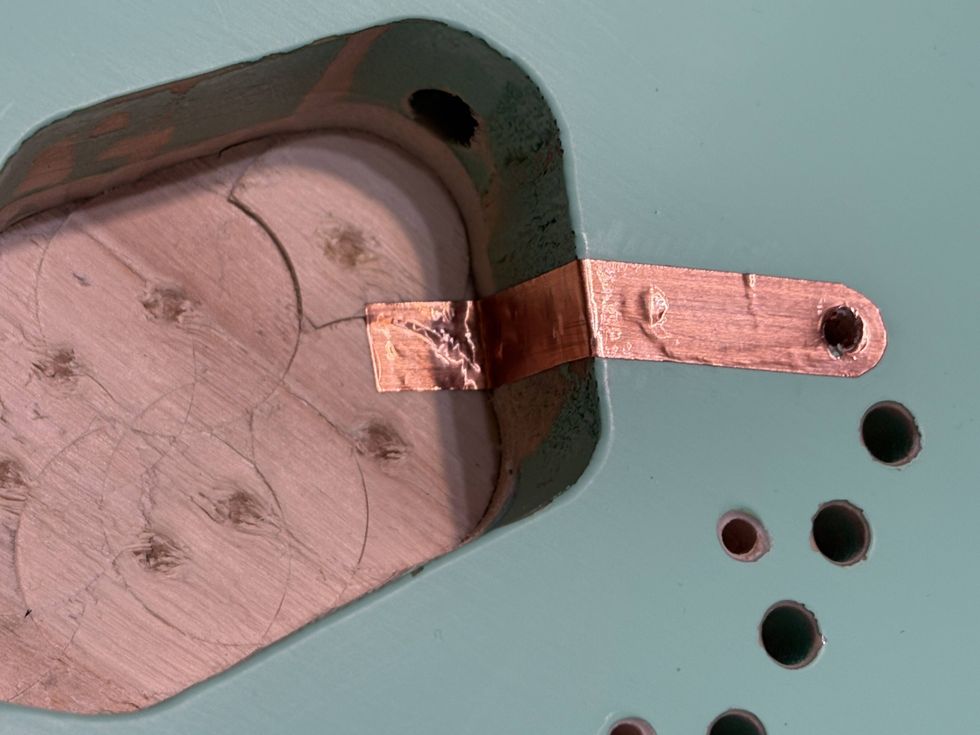

An x-ray of Dave Brewster’s “boxer’s break” to his right-hand knuckle.

It’s every musician’s nightmare to envision suffering significant injury to either hand. Whether it’s a bad sprain, a fracture, or a repetitive stress injury, the very idea strikes fear into our hearts and stokes paranoid fears about how well we’ll be able to play our instrument after the wound heals—or whether we’ll be able to at all.

Until the incident chronicled here, the only time I’d broken a bone was when I was 11 and fractured my ankle. I wore a cast for a summer, limped around on crutches, and basically felt like a moron both for breaking it and how it messed up life during those months. When it finally healed, the cast came off and I was running around my neighborhood again like nothing had happened.

Fast-forward 20 or so years, and I’m a professional musician at Quad Studios in Nashville, just a few days before Thanksgiving. Two nights before the session, the vehicle that my equipment was stored in was broken into, and around $6,000 worth of equipment was stolen—including my prized Gibson Les Paul Standard, a fully stocked Pedaltrain pedalboard, and my in-case-of-musical-emergency accessory backpack (aka “The Oh Shit Bag”).

Needless to say, I was in shock when I discovered my loss the next morning. I looked over the crime scene for a few minutes, then went back into my hotel, got in the elevator, and headed up to my room to get my phone so I could make the necessary calls.

While standing in the elevator, trying not to think about some criminal strumming my guitar or (more likely) selling it somewhere for way less than it was worth, I had a burst of rage and punched the wall without looking where I was punching or how close to the wall I was standing. It wasn’t the smartest thing I’ve done in my life.

My First Mistake

I immediately knew I was in trouble. My

hand—my right, picking hand—throbbed

with pain and began swelling instantly. Just

as painful was the thought of how I was

going to complete my recording session.

Luckily, I’d taken my Strat to my room the night of the robbery so I could play a little while I had the night off. At least I had one guitar and my amp to make it through the session, but I was mortified about the extent of the damage to my hand. I spent the night in my hotel room with my hand on ice and hoped for the best.

The following day, my hand still hurt and was very swollen—my ring- and pinky-finger knuckles were nowhere to be seen—but I was able to move my fingers. I figured that was a sign everything would be okay once the swelling went down, so I didn’t go to the hospital for an x-ray and attempted to play at the session that day.

Five-Fingered Delusions

I arrived at the studio early, got out my

Strat, and ran through a series of warmups

to see the extent of the damage to my

hand. Although I could do basic picking

exercises and scale sequences, I decided

against anything fancy or challenging, like

tremolo- or sweep-picking, and focused on

strumming, using downstrokes, and basic

alternate picking. Within reason, I was able

to perform what I wanted, so the recording

session began.

Brewster contrasts the painful poofi ness of his picking hand with his unharmed fretting hand in the studio after his “fight.”

Luckily, after I played along with the initial run-through of a song (“Time Bomb” by Jason Sturgeon) to help capture a good drum take, I had a break for a couple of hours. Second guitarist Brett Houchin and the session bassist re-recorded things, worked with tones, and tightened their parts. This gave me more time to assess damage and see what I could and couldn’t perform.

Still under the delusion that I could self-diagnose my malady, I figured if I could pluck a series of harmonics with my index and pinky fingers, it meant my hand wasn’t broken and that I’d eventually be okay. I sat there, guitar on my lap, debating whether to attempt it or not—there was still a lot of pain.

I positioned my hand and plucked the high E. It resonated quietly from my unamplified guitar.

I breathed a sigh of relief.

Then I double-dog dared myself to perform a series of plucked harmonics, ending with a Lenny Breau-style harp harmonic across the notes of an E9 chord.

I could do it! I knew my hand couldn’t possibly be broken … knew I would be fine in time.

After a few hours, it was time to lay down my rhythm parts, fills, and possibly a solo. Everyone in the studio was aware of what I’d done to my hand. I cruised through the rhythm parts with little to no trouble, and even added a new part during the outro of a tune.

When it came time for the solo, I hadn’t worked anything out beforehand, but I could hear what I wanted to do in my head. Although I could almost pull it off, my injured hand held me back. It was getting late and it was Thanksgiving the next day, so we called it a day. We needed time to get back to our hometowns, and my hand needed time to heal. We decided to finish the song sometime after the holiday.

Much to Be Grateful For

I nursed my hand as much as I could on

Thanksgiving Day. I was surprised when I got

a frantic phone call during the meal—my stolen

guitar had been listed for sale on Craigslist!

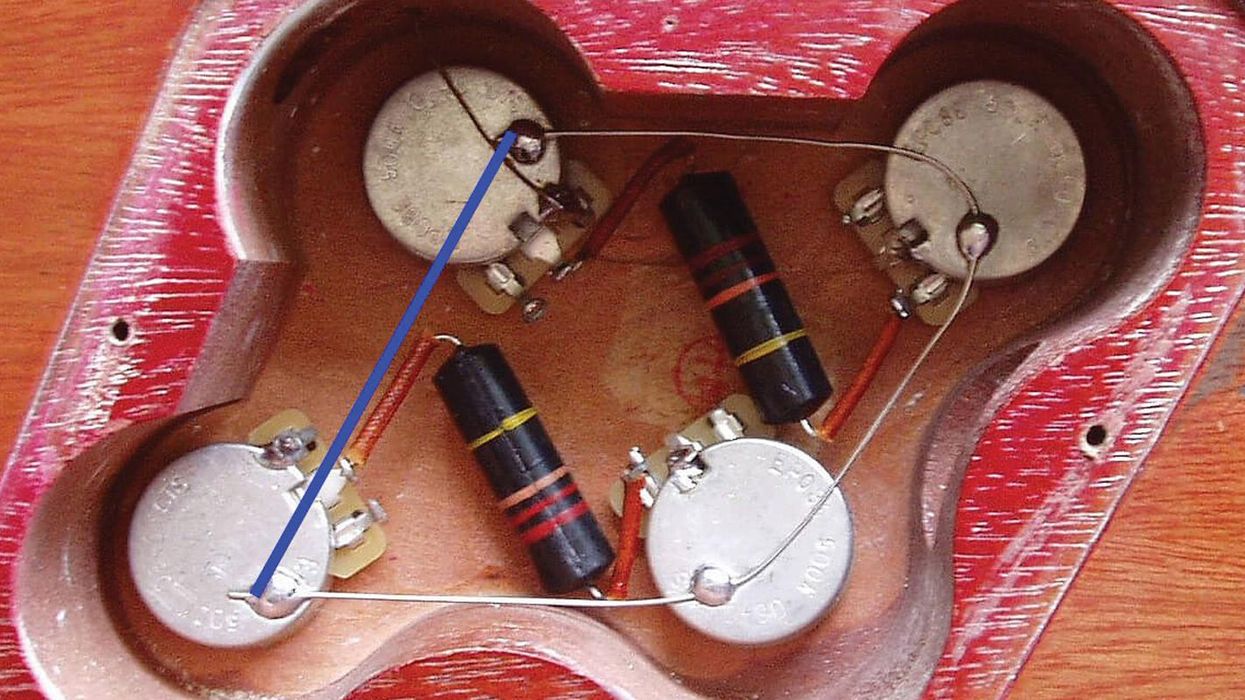

I wound up going back to Nashville the following morning and, miraculously, the police recovered my Les Paul—but that was all. All my other gear was still missing. Still, I thought I would never see my Paul again, so I was beyond grateful.

The first thing I did when I got home was remove the strings, give her a good cleaning, and slap on a new set of strings. I felt violated, and I couldn’t stand the thought of there being any remnants of the thief—fingerprints or dust or whatever—on there any longer.

I carefully played it and held it for a few hours. Under normal circumstances, I would have unleashed a guitar-mageddon jam session, but my picking hand was in no shape to perform much for an extended period of time.

Before long, I found out there was a deadline for the song we’d been in the midst of recording, so I needed to head back to Nashville. The problem was, my hand looked and felt just as it did the day of the incident. I started to worry, and I finally went to the hospital for an x-ray.

It was broken.

The Road to Recovery

I had an hour-long wait between getting

x-ray results and talking to the doctor about

the plan for my hand. My mind raced

through every conceivable variable: I wondered

how severe it was, what the long-term

effects might be, and what it meant for

my future as a musician.

The doctor assured me I would be fine in a matter of weeks. I had what’s known as “boxer’s break”—a slight fracture just past the knuckles. I didn’t need a cast or surgery, I just had to wear a removable hand brace for a few weeks.

After telling the doctor what my profession is and that I needed to finish a recording, I asked if I could continue to play guitar during the healing process. I expected the worst possible news, but to my surprise he said playing guitar—in moderation—would actually be good for my hand. I breathed yet another sigh of relief, then went home, packed my bags, and tried to rest my hand as much as I could before the trip back to Nashville.

Back at the studio, I was turbocharged. I knew I had to use my beloved, recently recovered Les Paul for the session, and I was ready to nail the solo that I’d struggled with less than a week before.

It only took two or three takes before I’d captured what I wanted for the solo. I also tracked some fills and a few slide parts. The song turned out great, and I felt a huge sense of accomplishment and relief as I left the studio that day. My hand was going to be okay, my guitar was back, and the song was finished. I felt vindicated and revitalized.

After consulting with my doctor, I waited a few days before picking up a guitar and spent some time coming up with a physical therapy regimen—a custom exercise routine that I’d use to rehabilitate my hand over the next several weeks. Here’s what I came up with.

Note: If you have a hand injury, consult a physician before following any part of this regimen.

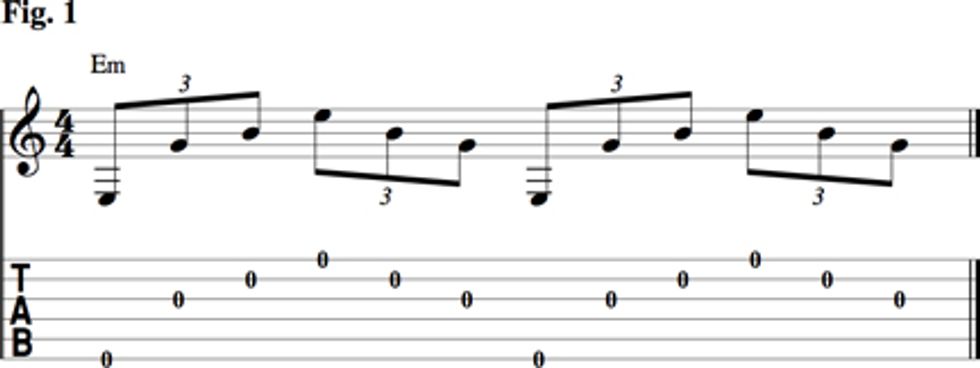

Phase I: Fingerpicking

Warm Up: open-String Plucking

My warm-up is the simplest thing I could

imagine playing with a broken hand—fingerpicked open strings. I couldn’t stop

thinking of the intro section to Metallica’s

“Nothing Else Matters.” Fig. 1 shows the

variation I played to begin my recovery. It’s

very easy, but not when you’re injured.

Arpeggios

I also practiced fingerpicking exercises from

Mauro Giuliani’s 120 Arpeggio Exercises,

which is required learning for pretty much

any classical guitar student, but also great

for any guitarist interested in developing

a solid fingerpicking technique. It begins

with basic arpeggios using a simple C–G7

progression, but things get crazy and technical

pretty fast as you move through the

exercises. By the end, you’ve exhausted just

about every conceivable pattern one could

perform with the progression. Fig. 2 is a

great place to start.

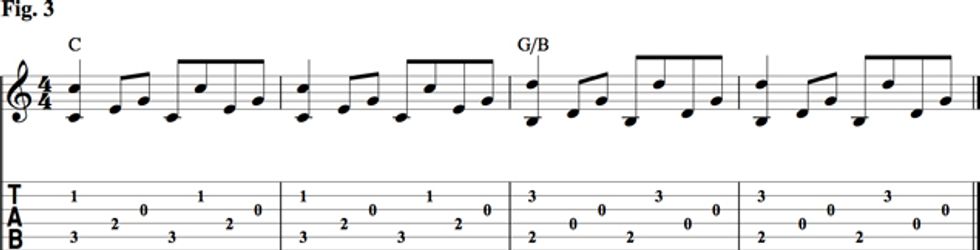

Simple Songs

Next, I played the fingerpicked sections of

Kansas’ “Dust in the Wind” several times—it was a good test to see if my hand was up

to the more musical, less rote passages of an

actual piece of music. I found that I could

do it, but much slower and with more caution

than I’ve ever played this classic tune.

Fig. 3 on pg. 135 shows a similar Travis-picking

exercise that will also do the trick.

Slow and Steady

Over the first several weeks, I used these

ideas and others to slowly regain strength in

my right hand. My starting tempo for each

exercise was a turtle’s pace, so be sure to

start slow and pay attention to the minutiae

and how you might be able to improve the

overall sound and execution.

Phase II: Flatpicking

Cowboy-Chord Arpeggios

The next area I focused on was picking

technique and right-hand control. Again,

I began slowly and comfortably, with exercises

that allowed me to focus less on what

my fretting hand was doing and more on

every movement of my picking hand. The

first exercise was a simple one I’ve used

with beginning guitar students for years.

I later expanded the basic concept into a

book called Power Picking (centerstreamusa.

com), but it involves taking a basic

“cowboy” chord—like a G major—and

turning it into a collection of melodic exercises

that are pleasing to the ear and great

for perfecting picking technique.

Fig. 4 is straight from my book. Play

through the exercise using only downstrokes,

then try it with alternate picking

(down-up-down-up).

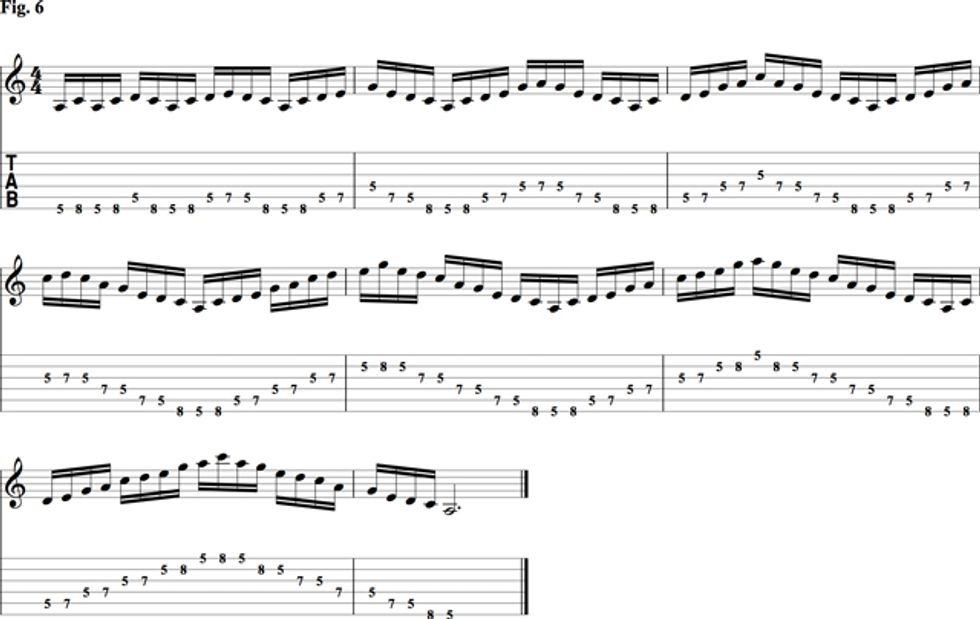

Scale-Based Arpeggios

Scale-based exercises are also extremely

useful. My “Suicide Laps” exercise (Fig. 5)

is named after a series of running exercises

from my high-school gym class, and it

involves playing the first two notes of an

A minor pentatonic scale, starting over

again and adding the third note, working

your way back down to the first note, then

working your way back up through the

scale to the fourth note, then back down

again, and so on. To really let out your

sadistic inner gym teacher, follow the rule

that says you have to start the whole exercise

over again if you make a mistake or

miss a note. It’s great for disciplining your

concentration abilities—especially after

you apply it to more complicated scales,

modes, and fingerings across the fretboard.

After having his Les Paul stolen and breaking his hand in frustration, Brewster and his remaining Strat managed to still lay down tracks for Jason Sturgeon’s

“Time Bomb.”

Lessons for Life

Hopefully, you’ll never be foolish enough

to punch an elevator or unlucky enough to

suffer a serious injury to your most valuable

assets as a musician. But the exercises shown

here can still be a great starting point for

developing strength, accuracy, dexterity, and

even some compelling musical ideas.

Hand-Injury Prevention Q+A

By Dr. Otto W. Wickstrom III, M.D.

What are some basic things musicians can do to help avoid injuries

such as carpal tunnel syndrome or repetitive strain injury?

Taking frequent breaks is the most important—even 30 seconds to a minute

can make a difference. Five-minute breaks are ideal. And gradually increase

your playing time—don’t take two months off and then try to play for four hours

straight. Anti-inflammatory medications such as ibuprofen can be your friend,

too, but beware of stomach and kidney problems that can arise if you take too

many. To help avoid this, always take them with food.

What are some warning signs that you might be developing or have a

hand or wrist condition?

Pain! Don’t ignore it or try to play through it. Numbness, a tingling in your fingers,

or having your hand “fall asleep” at night are the first signs of carpal tunnel syndrome.

See a doctor if you regularly experience these symptoms.

What are the most common types of treatment for hand and wrist conditions

such as carpal tunnel syndrome?

First, a wrist splint at night and nerve-gliding exercises. Next comes a steroid

injection, which is very helpful if done appropriately. Surgery is performed when

symptoms become constant and there’s no relief from previous treatment. Again,

do not ignore pain, because your symptoms can become permanent if they’re not

treated. A nerve that is pinched can die if it remains pinched too long, and you

can’t fix a dead nerve.

David Brewster is an honors graduate from the Atlanta Institute of Music who has authored several books available from Hal Leonard, Cherry Lane, and Centerstream. He is currently touring and recording with country-rock artist Jason Sturgeon. He would like to thank Jason Sturgeon, Dr. Wickstrom, Detective Holton, Scott and Julie at Jim Dunlop, and everyone else who helped him through his recovery. davidbrewstermusic.com

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

The Allparts team at their Houston warehouse, with Dean Herman in the front row, second from right.Photo by Enrique Rodriguez

The Allparts team at their Houston warehouse, with Dean Herman in the front row, second from right.Photo by Enrique Rodriguez