“It’s a few genres combined into one. It’s like progressive metal, progressive jazz … space metal,” says Tosin Abasi, founder of Animals as Leaders, when pressed to pigeonhole his band into a category. And he’s right—in the course of a single AAL song, your ears might be assaulted by math-metal djent-isms with bittersweet Lydian sonorities, tapped open-voice triads, contrapuntal textures, 8-string slapping and popping that sounds like a cross between Victor Wooten and Eddie Van Halen’s “Mean Street,” and lo-fi electronica-influenced tones.

On the surface, this description of AAL’s musical mélange might reek of the sort of music-school pretension you expect from guys who wear Jaco Pastorious T-shirts and throw in every new device they learn in theory class to create a hodgepodge of faux eclecticism. But Animals as Leaders weaves every twist and turn so organically that it never sounds forced and, after a couple of listens, almost doesn’t make sense any other way.

Many got their first introduction to Abasi’s virtuosic style on Animals as Leaders’ self-titled 2009 debut, which garnered intense praise from fans like Steve Vai. Explaining its unusual origins, Abasi says, “That album was essentially a studio project done with [Periphery guitarist] Misha Mansoor and myself. There was no band present.” In contrast, Animals as Leaders’ latest release, Weightless, which made it to No. 1 on the Amazon metal charts and hit No. 80 on the Billboard Top 100—no small feat for an all-instrumental act—marks the change from a studio effort to a real band. Abasi recruited 8-string guitarist Javier Reyes and drummer Navene Koperweis to flesh out the lineup. If you’re wondering why another 8-string slinger, rather than a bass player, was brought into the band, Abasi explains, “I’ve written music with Javier before. He’s one of a few guitar players I’ve actually had an effortless sort of rapport with. He’ll always think of different ways to complement what’s already there. For instance, he has a good handle on diatonic chord harmonies, so he’ll invert the chords that I’m doing.”

Animals as Leaders is perhaps the most groundbreaking progressive metal band of the current generation. In fact, it’s probably safe to say that they’re the genre’s game-changer. One of the secrets to their success is the accessibility of their music. Unlike some progressive bands that play epics with so many sections that you need to pop a couple of Ritalins to keep focused, AAL keeps things pretty concise. The longest cut on Weightless clocks in at a mere 5:16. Asked about this, Abasi says, “The songs on the new album are shorter— usually just three to four parts per song. It was more about taking a look at the fact that we don’t have a singer, and thinking of what would really ingrain these compositions in the listener’s brain. We wanted to trim the fat and distill each song to its essential parts.”

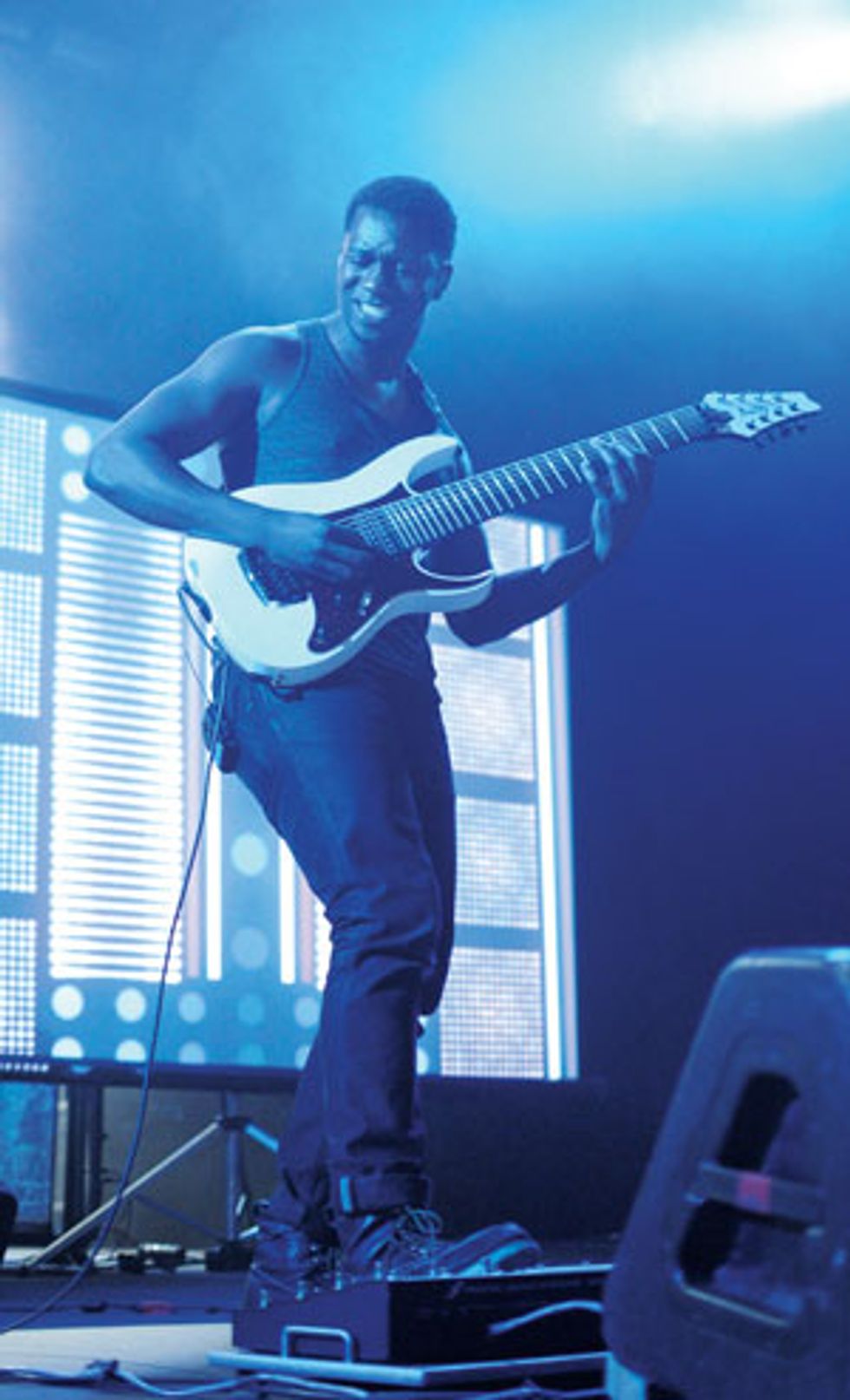

Guitarist Tosin Abasi

turning heads with

his tapped 32ndnote

flurries at a gig

in NYC on December

11. Photo by Sam

Charupakorn

Guitarist Tosin Abasi

turning heads with

his tapped 32ndnote

flurries at a gig

in NYC on December

11. Photo by Sam

Charupakorn Here, Abasi and Reyes talk about what set them on their unique paths and what they used to conjure the plethora of tones on Weightless.

How did you guys learn to play the

guitar—lessons, books, or by ear?

Abasi: I was self-taught. I was never that

good at really figuring out what someone

was doing and reproducing it. What I

would do is turn on the radio and improvise

over whatever was on. Inadvertently,

I was learning, “I can use Dorian over this

song or Mixolydian sounds cool here.” I

would wear out my REH or Hot Licks

videos of guys like Paul Gilbert and Frank

Gambale, learning the licks and some of

the concepts. That’s how I basically played

for 10 years or more. Then I went to a oneyear

music program at the Atlanta Institute

of Music in 2005. That’s the extent of my

formal music education.

That’s not too long ago. I’m guessing you

probably could already play pretty well

by 2005.

Abasi: The chops were already there. Music

school was more for learning chord construction

and understanding how to work

in a key, as well as learning jazz standards

and classical guitar stuff.

How about you, Javier?

Reyes: I had a number of teachers, all at this

one store. My main teacher has been Julio

Sosa. He lives in Washington, D.C., and is

relatively unknown but is phenomenal. He’s a

master of his craft. I started with him when

I was probably 11 or 12 and continued until

I was 15 or 16. Probably about six or seven

years ago, I started studying with him again

and almost became his apprentice, if you

will. I took it to a way more serious level.

Were you also into rock or was it classical

right off the bat?

Reyes: Well, it was a little of both. My first

teacher was a flamenco teacher but then

maybe a year after, my older brother was

playing the electric guitar—so I also wanted

to do it. I started learning Beatles and

Rolling Stones stuff. Then I started with

Julio Sosa and stuck with the nylon-string

for a while. I always played 7-string electric

on my own. I was into metal and listened

to Pantera and Dream Theater and stuff

like that. I was always looking for bands

that highlighted guitars—a little bit of

everything … classic rock, Judas Priest.

What were you listening to growing up,

Tosin?

Abasi: Before I got a guitar, it was whatever

was on the pop charts, like Guns N’

Roses and Michael Jackson. I got a guitar

when I was 12, during the beginning of

the whole alternative scene, so it was a

lot of Nirvana, Smashing Pumpkins, and

Soundgarden. My older brother was playing

drums at the time, and he had better

taste than me. He got a lot of the Modern

Drummer Festival videos, which had really

technical players. That was the gateway

into bands like Dream Theater.

Let’s fast-forward to today. Are the solos

on the album worked out or improvised?

Abasi: They’re actually improvised until

they’re composed. I’ll play the solo section

over and over and flesh it out, throwing in

a few different ideas and angles of approach

until I figure out something that’ll work,

and then this will end up being the composed

solo. I feel like I’m going to get a better

solo that way. The solo sections for some

of the compositions are hard. You don’t get

a whole lot of choruses to really develop

your solo or anything like that. It’s like one

time through, usually at a very rapid tempo

and in an odd meter. That’s not my ideal

improvisational setting and not where I

feel too comfortable improvising.

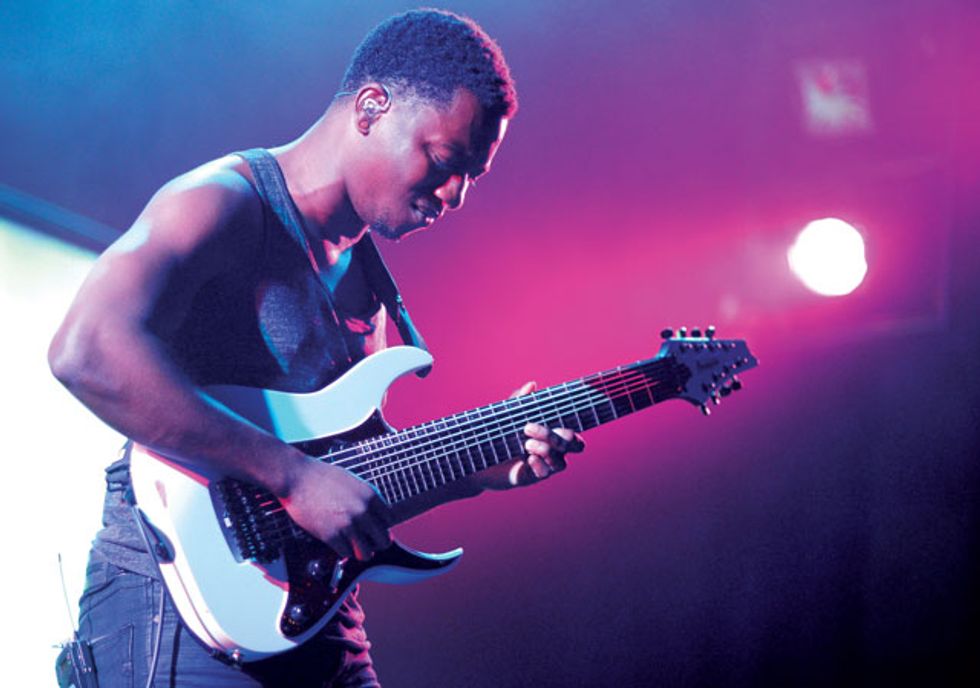

Javier Reyes asks a

soundperson to crank

up his Ibanez RGA

in the mix. Photo by

Sam Charupakorn

Javier Reyes asks a

soundperson to crank

up his Ibanez RGA

in the mix. Photo by

Sam Charupakorn

Do you use notation or charts to communicate

the band’s music?

Abasi: I read at a very basic level, but it’s

kind of de-motivating so I avoid it. We

don’t use charts or notation—everyone

basically plays by ear. A lot of the stuff

is very technique oriented, so I’ll have to

physically show Javier what I’m doing.

We record the music first, so the song

basically exists before we learn it as a

band. Then we go and learn our individual

parts. After the riff is tracked, Javier

will listen to it and either learn it by ear,

or if he had any questions, I’d clarify.

Reyes: For my own personal practice, a lot of times I’ll play along to the song. I’ll take sections and analyze them, count them out if I need to, and make my own little cheat sheet with the counting—but not necessarily in staff form. I’d just write [something like], “There’s three beats here, then a two-beat rest, then Navene’s going to do a two-beat roll.” I rely on a lot of muscle memory and intuition.

Abasi: We’re really heavy on phrase memorization. I don’t want to make any riffs that are so counter-intuitive that you have to count seven 16th-notes. We use the meters as a guideline, like, “Dude, you’re playing an extra beat because this is in 9/8.” We’ll do stuff like that, but at the end of the day it’s about internalizing the phrase of the musical line. I think that’s the best way to approach this stuff.

You guys play a lot more counterpoint

than many of your peers.

Abasi: Yeah, I’m an intermediate classical

guitarist—if I can even call myself that—

so it’s kind of a by-product of knowing a

bit of classical and then trying to utilize

its strengths. On an 8-string guitar, if you

drop the pick and use your open right hand,

you can play multiple lines at one time, basically

like playing classical guitar.

Reyes: I’ve been doing the classical and counterpoint stuff for a while, so learning Tosin’s stuff didn’t seem like a big deal. It’s allowed me to learn all this stuff.

In some ways, you guys are like an electric

version of the Assad Brothers classicalguitar

duo.

Reyes: Yeah, Tosin and I actually saw them

a while ago. I got introduced to the Assad

Brothers through my teachers back in D.C.

Abasi: Their harmonic approach is a bit more varied and adventurous than most traditional classical music. They’re technically proficient, too, which is obviously really nice. So, yeah, there are some parallels. Seeing them live was, like, “I didn’t know you could play at that speed with that amount of dynamics and detail!” It was phenomenal.

AAL is guitarists Javier Reyes

(left), Tosin Abasi (right), and

drummer Navene Koperweis.

Photo by Jonathan Weiner

AAL is guitarists Javier Reyes

(left), Tosin Abasi (right), and

drummer Navene Koperweis.

Photo by Jonathan Weiner

Do you guys still woodshed for hours

on end?

Reyes: Tosin is definitely more of a speed

shredder, doing all this crazy technique

stuff. I’m kind of just playing the parts that

need to be played.

Abasi: On tour, there’s a lot of song maintenance, and then I do general things that keep me limber. I’ve got a hybrid-picking book [that I study], which is basically chicken-pickin’, but it’s not about country music. The book has lots of permutations of left-hand fingerings. It’s all chromatic, four-frets-in-a-row stuff, but they’re dispersed in these sort of mathematical permutations.

Is the book you’re referring to Hybrid

Picking for Guitar by Gustavo

Assis-Brasil?

Abasi: Yeah, it’s a good book. I got his first

hybrid-picking book when I was in music

school, and two Animals as Leaders songs are

inspired from those exercises. That stuff is useful,

even if you’re just writing lines. The first

half of it is just these atonal permutations,

which is nice because you can turn them into

whatever scales or modes you want to use.

In songs like “Somnarium,” among others,

it sounds like you’re drawing from

the modes of the melodic minor scale.

Abasi: Yeah, that’s exactly right.

In metal, you sometimes hear harmonic minor

and diatonic modes, but not

too many people in the genre explore

melodic-minor modes—which are more

common in jazz-fusion—to the extent

you guys do.

Abasi: When I was in music school, we

covered all the modes—major and minor

scales—but then we went into harmonic

minor and melodic minor. That’s where

my ear started to peak, because you get

the intersection of a major seventh and a

minor third in the same arpeggio, which is

pretty cool. We have all these colors available.

Most tonalities are pretty directly

uplifting or diminishing, but with some of

the modes of these obscure scales it’s definitely

like a sweet-and-sour situation. I’m

kind of obsessed with these tonalities that

kind of blur the lines.

The calm but

deadly Reyes

catches a groove

at NYC’s Best

Buy Theater.

Photo by Sam

Charupakorn

The calm but

deadly Reyes

catches a groove

at NYC’s Best

Buy Theater.

Photo by Sam

Charupakorn

Javier, when Tosin uses an unexpected

scale or plays sort of atonal, does that feel

natural to you or do you have to acclimate

your ear to it?

Reyes: A little bit of both. If the rhythm

and the progression aren’t too crazy, I can

find a melody somewhere in there. I like

to look for melodies that lead you somewhere

else—shifting around in modes and

things—but I’m not actually paying attention

to that sort of stuff. After the fact I can

say, “I guess I’m in Lydian” or whatever.

“David” has a great ethereal vibe and

some really nice interplay between the guitar

parts. Did you write that one together?

Abasi: No. I just used my ear and little bit

of theory to come up with the second part.

“David” is actually inspired by Gustavo’s

book as well. I was working on an exercise

and thought, “Wow this is really cool.” I

just changed some intervals, changed the

rhythm a bit, looped the main theme into

my Boomerang [Phrase Sampler pedal], and

then messed around with another part—I

think it was an inversion of the same chord.

Let’s talk about gear now. You guys are

Axe-Fx users, right?

Abasi: Yeah, we’re using the Fractal Audio

Systems Axe-Fx II, and that houses all the

effects, as well as our amp tones. It’s a simulator,

so we just go directly back into the PA.

Reyes: We have absolutely no amps onstage.

What about guitars?

Reyes: I use Ibanez RGA8s. One is stock,

and the other is a custom with a bubinga

top and an ash body, but with pretty much

the same specs as the stock one.

Abasi: I have quite a few custom Ibanez guitars— all are 8-strings. I have a hollowbody 8-string that was made just for me, and it’s unique because it’s actually a neck-through design with hollow wings. It’s an [Ibanez] RG shape with a slight arch to the top, but I cut an f-hole in it so it looks like a semi-acoustic instrument. I also have a handmade guitar from a luthier named Ola Strandberg. It’s very unique—the neck profile is actually an asymmetrical trapezoid, so it’s thinner on the treble side, and it expands on the bass. It’s a fanned-fret guitar, too, so it’s multi-scalar.

What are the advantages of the fanned frets?

Abasi: Basically, there are certain pitches

that should exist within a certain scale

length. Once you start to go into bass territory,

you benefit from a longer neck just for

temperament or tension. So the multi-scale

[neck] combines a longer scale for your bass

notes and a shorter scale for your treble

notes, and what you get is a progressively

slanted sort of fretboard. That way, you

don’t have a neck that’s super long for your

treble strings—which makes the timbres

sound unnatural or the tension too high—

and you get enough tension for the lower

strings. You get the best of both worlds.

Abasi tearing up “An Infinite

Regression” with one of

his custom Ibanez 8-strings.

Photo by Sam Charupakorn

Abasi tearing up “An Infinite

Regression” with one of

his custom Ibanez 8-strings.

Photo by Sam CharupakornIn addition to having fanned frets,

your Strandberg is also headless. Do you

think headless guitars will ever make

a comeback, or will they always be

a niche thing?

Abasi: It’s hard to tell, because I don’t

really think like a normal guitarist. There

are a lot of traditionalists who say they

wouldn’t ever play active pickups or

who think a guitar should only have six

strings. So a headless guitar is a turnoff

to someone who’s really into Fenders or

something. Beyond writing progressive

music, I’m pretty progressive minded in

general. I really like for things to evolve,

because that usually means the design is

being refined and actually making our job

easier. So I would love to see more builders

taking a completely objective approach

to guitar building as opposed to relying

on tradition 100 percent.

Speaking of being progressive, I’m guessing

that knowing what you’re listening to

now might hint at what’s to come in the

future. Who are your current influences?

Reyes: I take ideas from classical guitarists

like Agust’n Barrios, as well as more modern

artists like Dirty Projectors and different

electronic DJs. I listen to their sound

design and how they produce.

Abasi: Jimmy Herring’s a recent discovery. He gave master classes at the music school I went to. He’s got a lot of hip, melodic ideas that are totally taken from bebop but he’s not playing straight-ahead jazz. He’s got a great sort of blues element to all of it. I’m also into jazz guitarists Kurt Rosenwinkel and Adam Rogers, as well as bass players like Matthew Garrison. I just found a really old John Scofield master class, and the playing on it is just phenomenal— really cool ideas. So, apparently now I’m a Scofield fan.

It’s interesting that you mention

Rosenwinkel and Rogers, because the

clean interlude at 1:41 in “Somnarium”

sounds like something Ben Monder,

another modern jazzer, might write.

Abasi: Ben Monder, yeah he’s very cool and

has a very bold sense of harmony. It’s cool

that you’re bringing up all these players,

because these are the guys that I’m listening

to who are really inspiring me to push the

melodic envelope. But when it arrives in

metal, it sounds even more striking because,

like you said, there are some decided tonalities

that are expected.

Would you ever go in a jazzier direction?

Abasi: Those guys have been influential in

terms of the chord voicings that I use and

the melodic blends I’m trying to create—it’s

just ending up in this sort of metal context.

Would I ever go that complete route? I’m

not the improvisational player that those

guys are, but I think that part of my brain

always wants to be part of that world to

some degree. The music is definitely really

compelling and stimulates my creativity,

but I’m not necessarily concerned with

straight-ahead jazz as a genre or post-bop or

whatever you want to call it.

Reyes: Just knowing Tosin’s personality, he’s all about just writing whatever he wants to hear. How we grow as musicians is how the next album is going to progress. If it tends to be jazzier [than the past], then that’s what it is. If it tends to be more metal, then that’s what it is.

Javier Reyes' Gear

Guitars

Ibanez RGA guitars with DiMarzio

D Activator 8 pickups.

Effects

Fractal Audio Systems Axe-Fx II

controlled by Fractal MFC-101 MIDI

foot controller.

Strings and Picks

DR .010 sets with a .060 seventh

string and an .080 bass string for

8-string standard tuning (with the

eighth string tuned down to low E),

Jim Dunlop .60mm picks.

Tosin Abasi's Gear

Guitars

Ibanez RG2228 with EMG 808X

pickups, Ibanez custom 8-string

hollowbody, Ola Strandberg custom

8-string with fanned frets.

Effects

Fractal Audio Systems Axe-Fx II

controlled by Fractal MFC-101

MIDI foot controller,

Boomerang Plus phrase sampler.

Strings and Picks

DR .010 sets with a .060 seventh

string and an .080 bass string for

8-string standard tuning (with the

eighth string tuned down to low E),

Jim Dunlop .60mm picks.

Youtube It

For an up-close look at Animals as Leaders’ instrumental

prowess, check out the following clips on YouTube.com.

Dig an entire Animals as Leaders concert

from Kosmonavt in St. Petersburg, Russia,

on September 29, 2011.

Animals as

Leaders “Cylindrical Sea” LIVE 11/8/11

in Indianapolis IN

Abasi employs unorthodox techniques

to create an otherworldly effect at the

House of Blues in Houston, Texas, on

November 17, 2011.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.