East Bay Ray, who was born in Oakland, California, in 1958 as Raymond Pepperell, is a punk icon. His band, the Dead Kennedys, launched what critics call the second wave of American punk and defined the sound of hardcore. Their music was aggressive, defiant, and the polar opposite of the synthesized cheese popular in the ’80s.

Their influence was immediate, too, spawning armies of copycats, and is still felt a generation later. Classic bands like Slayer, newcomers like Deafheaven’s Kerry McCoy, and many others cite them as a primary influence. Their controversial name and radical politics got them a lot of attention, but their legacy is their great songwriting and high-caliber musicianship. The Dead Kennedys spent countless hours crafting songs, perfecting arrangements, sculpting tones, modding gear, and nerding out in the studio. And their solid work ethic and professionalism stood in stark contrast to the mediocrity so prevalent in DIY punk.

The Dead Kennedys took their art seriously and were anything but one-dimensional. They played hardcore—East Bay Ray can rifle through quick successions of distorted power chords with the best of them—but they were much more than that. Spaghetti-western twang, slapback echo, and unorthodox clean tones were also integral to their sound. East Bay Ray toured with a vintage Echoplex, although he kept it in the rear of the stage on his amp and away from diving moshers. And he crafted a tone that had much more in common with ’60s surf than the sounds usually associated with punk and heavy metal. His diverse influences include his father’s collection of swing and delta blues 78s, Merle Haggard, the Ohio Players, and the music his mother listened to.

“My mother was into things like the Weavers, Pete Seeger, and Frank Sinatra,” he says. “And my father took my younger brother and I to see Lightnin’ Hopkins—we were too young to drive. We also had him take us to see Muddy Waters, who we’d learned about through the Rolling Stones.”

In 1986, when the Dead Kennedys called it quits—at least until reuniting with a new singer in 2001—East Bay Ray stayed busy recording and producing. He played on Sidi Mansour, an album of Algerian Raï music by vocalist Cheikha Rimitti that also features Robert Fripp and Flea. He was involved in projects with groups like Hed PE, Frenchy and the Punk, Pearl Harbor, Skrapyard, and many others. He’s featured on Amanda Palmer’s “Guitar Hero” and recorded with Killer Smiles, his collaboration with Skip (aka Ron Greer, also the singer in the current DKs incarnation). He will be back on the road with the Dead Kennedys this summer.

Our plan was to write a retrospective article about East Bay Ray’s career and influence. But after speaking with him—and discussing his history, tones, gear, production experience, and insights in depth—we felt the conversation was just too good not to share in his own words.

When did you start playing guitar?

It was in high school. My father took me, my brother, and our friend John to a Rolling Stones concert. My dad waited outside. We were in the second or third row and it was just crazy—it was wonderful. Afterwards my brother took drum lessons, I took guitar lessons, and John took guitar lessons. After college I played in a bar band in Hayward, California, at the Bird Cage and the Sensuous Woman [laughs]. I was making money getting out of college and I said, “Oh wow”—you know, I was making $100 a week or something. Then I discovered punk rock at the Mabuhay Gardens in San Francisco. I saw the Weirdos playing. I said, “This is what I want to do.” I phased myself out of the bar band and put an ad up in Aquarius Records and Rather Ripped Records. Klaus Flouride (Geoffrey Lyall) and Jello Biafra (Eric Boucher) answered the ad.

What was the attraction to punk?

The energy. The little hairs on the back of my neck stood up. At the time, in the late ’70s, the radio was all disco and the Eagles. Neither one rocked my heart very much.

Yet your influences are very diverse—you can hear it in your music. Where do they come from?

Most good musicians I know listen to a variety of music. I love spaghetti western stuff. One of my favorite records of all time is Elvis Presley’s Sun Sessions—that is one of the records that inspired me to get an Echoplex, to get that slapback echo. I love the psychedelic stuff like Syd Barrett in the early Pink Floyd. In the ’70s I was listening to ’60s music, I guess. I had peculiar tastes. I was into funk music—Ohio Players are one of my favorites. I listen to a wide variety of music. Good musicians need that alternative influence. If you just listen to punk rock you end up sounding kind of generic. But if you listen to music outside of punk rock, you become more original.

Another thing is that punk rock is just a style, but the music underneath is very similar. One of the reasons our songs have lasted so long is the structure underneath has a lot in common with a Beatles song or a Motown song or even a ’30s standard. There are basic constructions underneath that make a song work that are applicable to a reggae song, a country song, or to a jazz standard—and it’s very similar across the different styles.

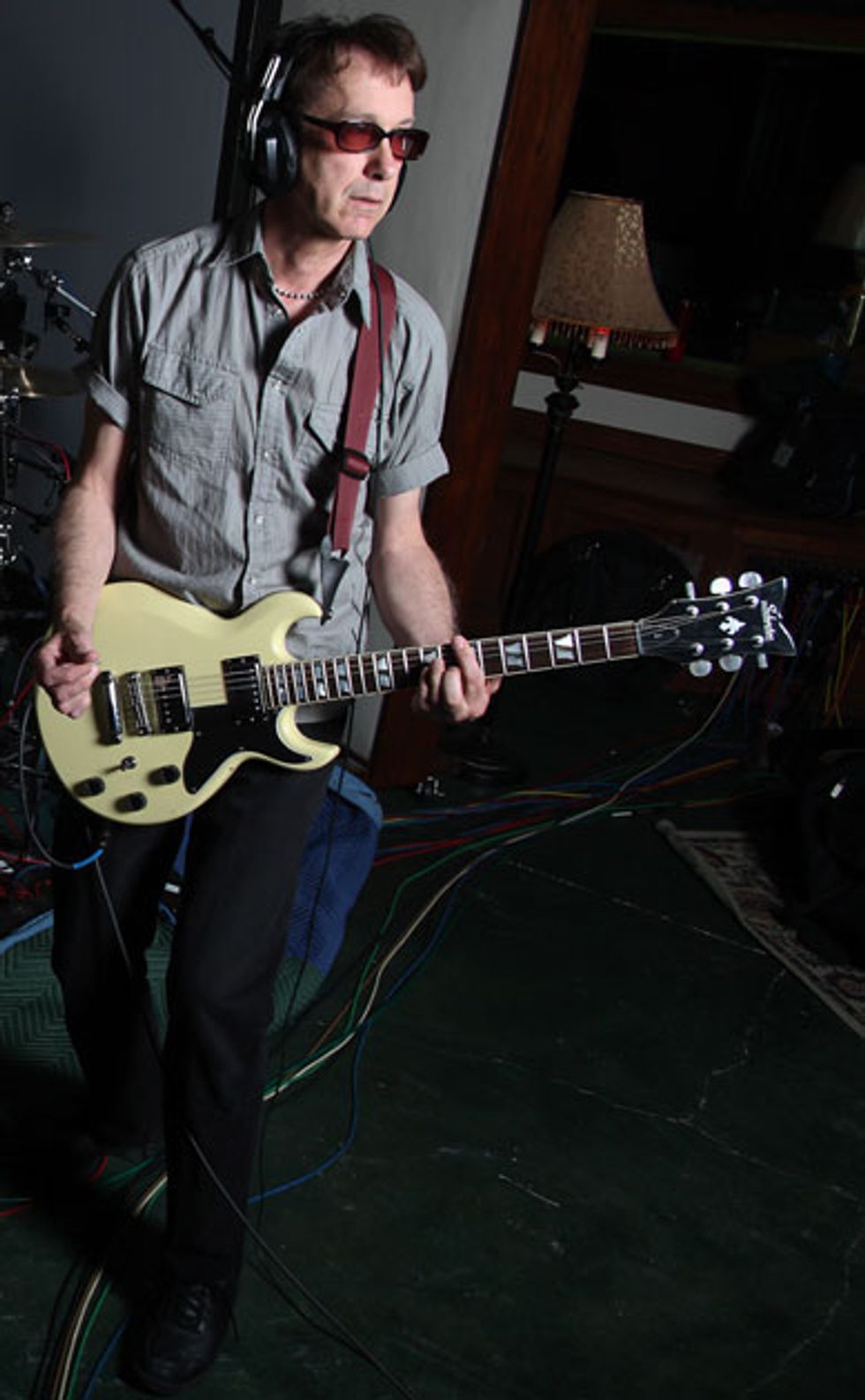

Looking like a Sun Records artist in his red shades and matching guitar, Ray says Elvis Presley’s recordings for the pioneering rock label inspired him to get an Echoplex. Photo by Pixie Vision Photography

The interesting thing is to make it different. I love this quote from the famous songwriter, Cole Porter. He says, “Make the familiar sound different and make the different sound familiar.” That’s one of the things we did: We made the familiar sound different. But also we have some songs that are in 11, 13, and 6/8 time, so we made the different sound familiar.

There is a lot of modal and atonal stuff in your music, too.

Even though I went to college and have a degree, when it comes to music I’m less intellectual and I don’t have a lot of super technique. I would come up with things that were outside the rulebook, because I really didn’t know all the rules at the time [laughs]. I played like that, and then afterwards I realized it was a total modal thing. But that wasn’t done deliberately and consciously; that was just done because I liked the sound.

For example, would “California Über Alles” be that kind of thing?

For that we said, “We’re going to do this kind of Boléro operatic style”—that one was more deliberate. I mean, all of the songs are different. Some songs are from jam sessions, some are more based on an idea that one of the musicians brought in. “California Über Alles” was one of the ideas that Biafra brought in. We just added dynamics and chord changes, but kept the basics.

One thing that distinguishes you from other guitarists is your twangy Fender tone.

I’ve had both Gibsons and Fenders. The original Dead Kennedys guitar was actually a Japanese knockoff of a Telecaster. I put a humbucking pickup in at the bridge. Fenders have a little bit longer scale and the strings go hard over the bridge down into the body, so they naturally have a bit of a twangier sound. That’s how my sound started: I liked the twangy sound with the fatter humbucking pickup. Like on “Holiday in Cambodia,” I play a bunch of arpeggios and they really ring out. I find on a Les Paul that they just don’t ring out as much. A Les Paul is good for one-string type stuff, because it is really fat, but when you start playing two strings it’s not as articulate as a Fender would be. But the stock Fender pickups are just way too low power for my sound.

And you have that gray Strat.

Yeah, that’s a Frankenstein Strat.

Was that also a Japanese knockoff?

I would not spray paint a real Stratocaster [laughs]. At the time I had a sunburst Stratocaster, but that [gray guitar] was basically Frankenstein parts. I bought the body, neck, and pickguard, and put it together. I may have taken the neck and the parts off the real Strat and put them on that guitar.

“I am a renaissance person,” the legendary guitarist declares. “I have a left brain and a right brain. If you listen to music outside of punk rock, you become more original.” Photo by Pixie Vision Photography

How about pedals? I assume with all the people jumping onstage that something would get disconnected or broken. Did you have pedals you kept on your amp in the back?

Yeah. If you look there is an Echoplex tape echo and it’s usually sitting on top of the amp. It had a foot pedal—just an on/off switch—which would be out onstage where I would be. As I remember, I found this foot pedal that was die-cast iron. It was very heavy, but it was easy to pull out of the way. Actually, sometimes somebody landed on it and broke it, but not very often. It was too small. Nowadays I only use two pedals: one is the Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler and the other one is the Boss CS-1 Compressor. I have it set so that it’s more volume boost than compression. I turn the output volume all the way up and then just turn up the compression so it’s a little louder than the straight guitar. That’s it, just two effects! It’s all in the hands man. [Laughs.]

Do you use the DL4 to emulate the Echoplex?

Yes. I use the analog-with-modulation setting. You can put a little of the wow and flutter in to give it a wetter sound. On the Echoplex, the tape has what is called wow and flutter. It’s a slow speed variation that gives it that really wet sound that digital things originally didn’t capture. The echo coming back off the tape is a different sound than the direct sound. It’s deliberate distortion—not trying to make an exact copy of the first note, but make it a different EQ, different frequencies, and a different pitch with a little bit of the wow. That’s what gives the Echoplex its wonderful analog wet sound that digital is clueless about.

Did you get your distortion from cranking your amp and controlling it with your volume knob?

It’s basically amp distortion. Our first singles, like “Holiday in Cambodia” and “California Über Alles,” and Fresh Fruit were recorded on a Fender Super Reverb. Originally I had those LPB-1 Power Boosters in front of the amp. But I’m also a science geek, so I got schematics for Marshalls and Boogie amps and rewired my Fender Super Reverb to have an extra tube channel in it so it would be like a master volume Marshall.

Really?

Yes, really. I’m a renaissance person. I have a left brain and a right brain [laughs]. I know a lot about why a Marshall sounds good and why a Fender overdrive doesn’t. And why Mesa is too much overdrive for me: You don’t get that clean surf or spaghetti-western arpeggio sound that I like.

One of the tricks is to put the echo unit before the amp. Recording engineers don’t like that. When I have the guitar’s volume down, it hits the echo and then it hits the amp. The echoes clean up as they go through the amp, because they’re at less volume. Recording engineers or some guitarists stick it in the loop in the back of the amp. They make the sound, process it, and then they add the echo—but that’s more like a post-EQ effect. I do it pre-EQ. Even when I’m maxed out—like with the compressor on, the amp up, and the guitar all the way up—if there is a piece of silence, if you listen to the echo, it cleans up. The last ones will be the clean guitar. It’s a less technical way to do it, but it’s a more musical way. It’s bad engineering, but more musical.

different sound familiar.

Why is it bad engineering?

For somebody who’s trained in engineering, “Each echo is different!” But from an artistic side, “Yeah. That’s what makes it more interesting—because they’re different.” Somebody trained in old-school engineering would not like to hear a distorted echo. You make the distorted sound and then you echo it, which is what would happen more in a natural world. For example, if you’re in a room that has a lot of echo and you hit a distorted guitar, that one distorted signal is what is echoed. In a room, the walls absorb some of that high end and each time it hits the wall it will absorb more. They change over time and the high end slowly gets cut on each echo. But what I’m doing is as it hits the amp, it has less distortion, too.

And, since you’re using your effects in an unorthodox way, you’re able to create a lot of different sounds.

Right. One thing I noticed—and this is my personal opinion—I have a lot of guitar player friends and have seen a lot of bands, but they have like 10 pedals down there on the pedalboard. In a live situation, I really can’t tell the difference that much. Now, in the studio, I’ll use many more pedals, because you can pick up the subtle nuances, but in a live situation the difference between a phaser and a flanger, for example, is very minimal. There is so much added by the room that the real subtle nuances can’t be picked up. But that’s just my opinion. I use a lot less batteries.

I saw a video of the original 1981 In God We Trust, Inc. sessions with the whole band playing together live. Was that typical of how you recorded?

No, it wasn’t. Generally, the drums would be in the big room, the bass and guitar amps would either be baffled off with gobos or in separate rooms—but the musicians would be in one room. The singer sang along so we would know where the dynamics and changes were. But the actual vocals you hear on the record were done later with him just listening in the headphones. You know, every musician is funny, like, “We’re going to record live in the studio”—and it never works.

Did you generally record multiple guitar parts?

There would be the original scratch guitar, which would probably not have a good sound. A lot of times I would double the guitar. The reason is that when you are in a club or a big hall, there are big amps or big drums and it’s filling things. But you need to sound good on a car radio or a small boom-box type system. We found that the doubled guitars kind of duplicated the power of a live performance coming through a small speaker.

Did you pan them left and right?

Generally, they’d be panned left and right if they were identical. If they were different we’d pan them more together, so that your ear wouldn’t get confused by the difference.

Today Ray frequently plays Schecter S-1 models, but with the DKs he favored Telecasters and Stratocasters for a tough-yet-twangy and clean sound. Photo by Pixie Vision Photography

How prepared was the band before going into the studio?

We were generally prepared. We’d spend time writing the songs, which we’d do with an acoustic guitar on a sofa. That way you can hear the structure and melody of the song much better. If you can play a song on an acoustic guitar, it’s usually a good song. You don’t get fooled by the groovy sound, so to speak. Then we would go to a rehearsal studio, play the songs with the full instruments, tweak the arrangements of the parts there, and actually write down what kinds of overdubs we wanted. Some of our songs, we’d have Paul Roessler from the Screamers playing keyboards and Klaus plays clarinet on “Terminal Preppie”—so that stuff was planned out. We’d work on the arrangements and see what was working and what was not before we got to the studio.

You are credited, even back in the early days, with producing and mixing. When did you learn your way around the studio?

I financed our first single, “California Über Alles/The Man with the Dogs.” We basically recorded that in one day, possibly two days—I think it was eight hours. We then tried to mix it. Everybody in the band was there. The mixes were coming out horrible and the problem was too many chefs in the kitchen. I said, “Let me go into the studio and mix it.” It took 30 hours of mixing and remixing for “California Über Alles,” and that’s where I learned how to mix—eight hours to record and 30 hours to mix.

The problem with hard rock and punk records is there is a lot of midrange. You have an aggressive snare, voice, and guitar in the midrange. That’s very unusual and it’s really hard to balance them. On a lot of records, the voice is in front. In more instrumental metal bands, the guitar is in front. But in punk rock we wanted the snare, voice, and guitar to be equal. So that took 30 hours.

For our next single, “Holiday in Cambodia/Police Truck,” we had a producer, Geza X, who did a really brilliant job, but it was the same thing. He did a mix, the band did a mix, and nobody liked them. I said, “Let me go in the studio without everybody yakking and remix them.” I remixed them and this time it didn’t take 30 hours. This time it took like five hours—actually less. I did “Holiday in Cambodia” in about four hours. The band voted that was the best mix, and that’s the single.

And there was no engineer in there pushing the buttons? It was just you?

No, there was an engineer there, but the decisions were mine. That 30 hours was my grad school at mixing. What I found—talking to engineers and stuff—is that punk rock is hard to mix. People think, “Oh it’s simple stupid music,” but it’s actually hard to mix because you have three elements in the midrange which are very aggressive. It’s really hard to get them to bounce in a small speaker.

What’s the secret?

I don’t know [laughs]. You have to listen. Actually, one of the tricks is to use as little EQ as possible. EQ tends to change the phase and that makes it more fatiguing. Later, our lead singer mastered a song, “Buzzbomb from Pasadena,” and he put like a 6 dB midrange peak in it in order to make it, quote, “sound aggressive,” unquote. That’s basically the telephone frequency. It made it really tinny and thin sounding and it’s also very fatiguing. You can only listen to it once or twice and then it’s like, “Ow, this is like fingernails on the chalkboard.” We discovered that when we remastered stuff and we were like, “Oh my God, this one is just a nightmare.” It takes experience and listening to a lot of stuff.

Did you have different tricks or experiments that you tried when miking guitars?

One of the things people don’t realize is that mic technique is very important. We learned this from day one: You can take a microphone on a speaker, move it a half inch, and get a totally different sound. There would be an engineer and he’d have an assistant—or I would do it—and we would move the mic a little bit and find the one spot that captures the full spectrum.

I actually do that live. I have my mic through the monitor and I move it around while we play until we hit that sweet spot. It’s pretty amazing how radical you can change the sound just moving the mic around. And it’s better to move the mic around than it is to add EQ. If you need a little brighter, move it towards the center, if you need it a little fuller, move it toward the edge—until you find that sweet spot.

Also, when we were doing overdubs, there would be one or two mics on the guitar and then there’d be a room mic—to pick up the room ambiance to make it sound more real.

Do you do that for every show and session? You don’t stick a piece of tape on the grill and say, “Put the mic here.”

Live, the backline is supplied so the speakers are usually a little different each time, but I know approximately the spot. Some speakers are bassier, so then I move it in. If it’s a brighter speaker, I move it out a little bit. It also depends on what microphone they use. Most people set the mic right at the center of the cone, and that’s like the brightest stuff. I can see the soundman cringing at the high frequencies rattling in his ear [laughs].

Do you have a preferred mic in the studio?

The Sennheiser 421 and the classic is the Shure 57. The room mic would be a Neumann condenser mic. That wasn’t hard and fast; we’d change it up just to keep it interesting.

Mic placement is really the key. If it’s not going into the microphone, everything you do after is not going to be very constructive. You get a good sound from the mic first and that will make everything easier. But it’s basically using your ears. The good thing is to always use a model. Play something in the studio, in the control room, so you can hear. The studios have really good speakers and really good mics and everything sounds good. You need to hear a record that you like—that’s mixed well and recorded well—in the room and then try to get in the same ballpark.

East Bay Ray’s Tonal Toolkit

Although East Bay Ray’s most often seen with a Schecter S-1 slung over his shoulders these days and frequently plays live through a Marshall JCM2000 DSL100 when he’s not using a promoter’s backline, his big, clean, and classic Dead Kennedys’ tones were mostly generated by a pair of Stratocasters—a gray spray-painted parts guitar and a sunburst model—and a Telecaster with a humbucker in the bridge slot.

Before moving to Marshalls, he employed a plenty loud Fender Super Reverb for the Dead Kennedys’ first singles and the album Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables. His longtime magic box was an Echoplex unit that he placed atop his amp and plugged into as the first stop on his signal chain, to give him more control over his often surf-like tone. Today he’s replaced the ’Plex with a Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler that he uses in a setting that emulates his old favorite, linked to a Boss CS-1 Compressor that he deploys primarily as a volume boost.

East Bay Ray Über Alles

East Bay Ray’s legacy is not only writ large in the annals of punk, it’s all over YouTube, starting with the historic In God We Trust, Inc.: The Lost Tapes. This documentary is the mother lode for DKs fans. It features the band live in the studio recording an early version of their classic album. The DKs usually cut basics and later redid guitars and vocals, which makes this full band session unusual. Of note is East Bay Ray’s gray spray-painted Frankenstrat. The music starts at 6:25 after a lengthy introduction.

Ray’s seriously Echoplexed guitar jabs ignite the song “Police Truck” at the 4:14 mark, right after Jello Biafra announces, “This song is dedicated to Dianne Banker-Butt-Licker-Margret-Thatcher Feinstein.” If you didn’t know better, you’d think the DKs were a political band. Although the stage is under constant punk assault, the guitar gear is left alone. Respect the Plex!

“Holiday in Cambodia” was one of the Dead Kennedys’ anthems and most controversial numbers. This live, in-studio performance, interspersed with gruesome war footage, displays Ray’s signature ringing arpeggios and aggressive Echoplex usage. You can catch glimpses of the unit sitting on his amp if you look carefully enough.

And last, there’s the band’s infamous live performance at the 1980 Bay Area Music Awards. The point of the song “Pull My Strings,” written especially for the event, was to make fun of everyone, but that didn’t stop East Bay Ray from playing an impressive solo at 3:35.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.