“Change" has been an operative word in the habitat of Cage the Elephant in recent years. The biggest development for the Kentucky-based band took place in 2013 when they essentially became a quartet following the departure of guitarist Lincoln Parish, who had been with the group since their formation in 2006. Filling the void left by Parish's exit is former Morning Teleportation guitarist Nick Bockrath, along with keyboardist/guitarist Matthan Minster.

Although Bockrath and Minster are officially “touring members," both contributed to the new album, Tell Me I'm Pretty, on which the remaining cofounders of Cage the Elephant—frontman Matt Shultz, his brother Brad Shultz on guitar, bassist Daniel Tichenor, and drummer Jared Champion—swapped their longtime producer, Jay Joyce, for the Black Keys' Dan Auerbach, who recorded the group at his own Easy Eye Sound studio in Nashville.

“It was time to do something a little different," says Brad Shultz. “We've been friends with Dan for a while, so that led to us touring together [in 2104] and eventually making this record. We love sitting around and talking about music with him. We discovered that we share a lot of the same opinions about songwriting and producing, and what makes a great record. Sometimes those conversations can be just like jamming—you're tossing stuff around and jumping on ideas."

“I was surprised at how quickly we moved from track to track with Dan," adds Tichenor. “The chemistry was there, and we knocked out a track a day. We spent probably three months working on our last record [2013's Melophobia], and that felt like a really long time. Dan kept us moving along. I think we did the whole thing in a month."

In addition to maintaining a brisk pace in the studio, Auerbach was instrumental in helping the band transform their sound on Tell Me I'm Pretty, moving away from the wild and woolly modern rock influences (Pixies, Arctic Monkeys, Nirvana) that won them the “Best New Artist" title in 2011's Rolling Stone readers' poll and embracing a smoother, more stylized production aesthetic that borrows heavily from '60s bubblegum radio. The loping melancholy of “Sweetie Little Jean" could easily segue into the Turtles' “Happy Together," and the sparky stomp of “Punchin' Bag" echoes the insistent bite of Paul Revere & the Raiders' “Kicks." Elsewhere, the band conjures up the spirit of late '60s proto-punkers the Seeds on the dark and moody rocker “Cold Cold Cold."

Brad Shultz and Tichenor spoke with Premier Guitar about Cage the Elephant's evolving sound, plugging straight into the console, crafting solos, trying out some of Dan Auerbach's instruments, and more.

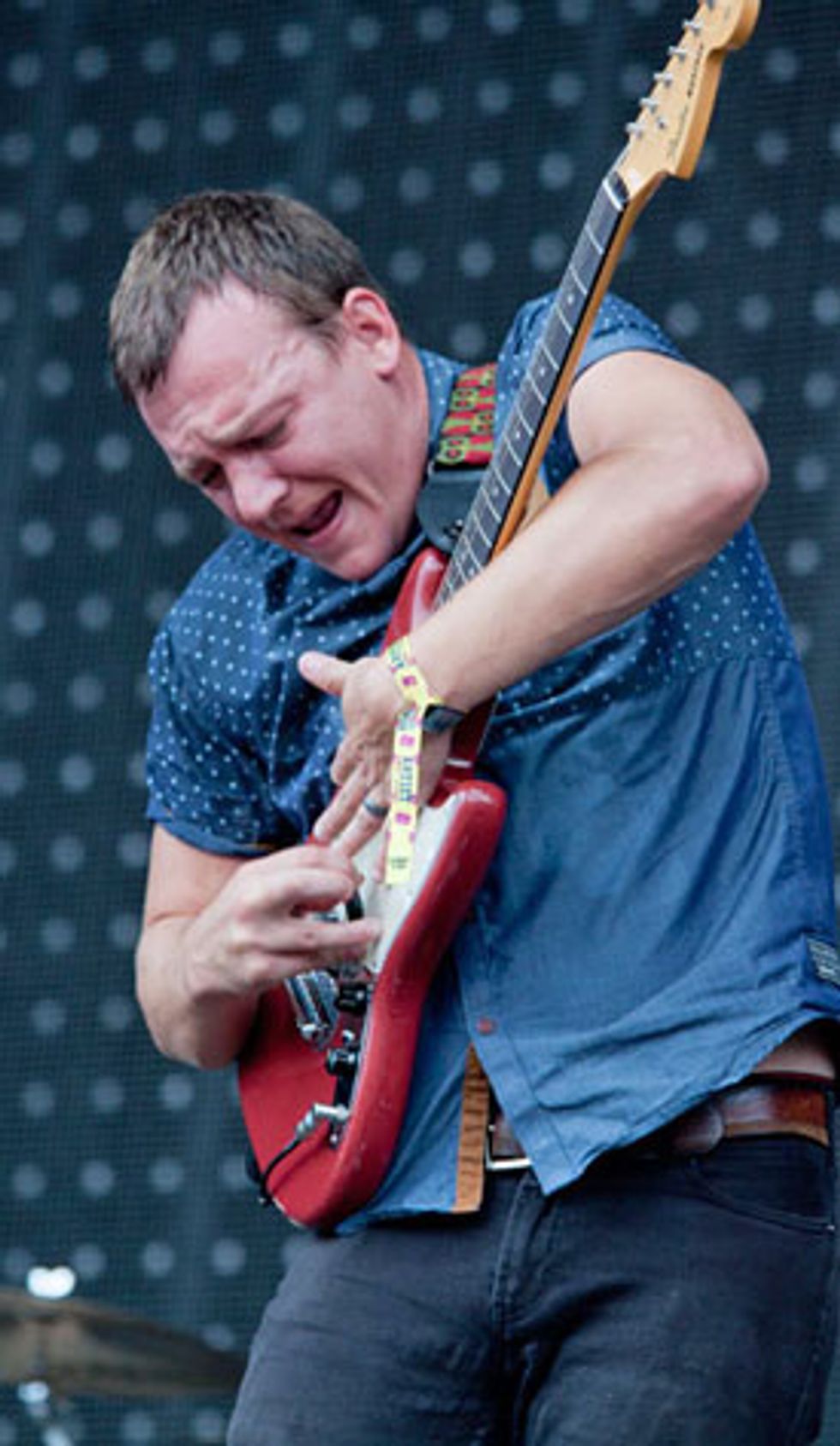

Brad Shultz makes his reissue '65 Mustang whinny, using his ring finger to slide down the strings for a slide-like effect, during Cage the Elephant's Lollapalooza 2014 set in Chicago's Grant Park.

Photo by Chris Kies

I understand Lincoln left the band on good terms. How exactly did it happen?

Brad Shultz: He left because he wanted to pursue other things—simple as that. He'd been touring since he was 15 years old, and I just think he wasn't enjoying the road as much as he had in the past. He wanted to stick closer to home, and he found a passion in producing. That's what he wanted to do. You know, that's cool—we understood.

What was the process of getting Nick in the band?

Shultz: Nick had been in several other bands before joining up with us, and one of those was Morning Teleportation. We were just in love with them—like, they were our favorite band in the world. When we went up to New York to mix Melophobia, Nick hit us up. We hung out with him, and he came by and listened to some of the mixes. He was loving that record.

We went along our own paths, and then Lincoln was going through some stuff, which led to him wanting to leave the band. We were doing the David Letterman show, which was going to be his last performance with us, and then Nick hit us up again. He was like, “I feel I need some change in my life." He was playing with another band at the time. I think there was something in the timing of it all. Lincoln wanting to leave, Nick hitting us up—it meant something.

Did you have any kind of audition, or did you just know that he'd fit in?

Shultz: We had a feeling he'd be right, but there were a couple of other people we really loved as guitar players and people. They all came down and jammed with us. You have to feel right about it. There are just certain nuances that have to be there so you can vibe with somebody musically. We jammed with Nick and a few other dudes, but it wasn't like we were doing auditions. It was just more playing and vibing out. It came down to Nick and another dude, and we went with Nick.

Daniel, how involved did you get in the writing and demoing for the new record?

Daniel Tichenor: I'm way involved. The four of us—me, Matt, Brad and Jared—sit around and work on stuff. This time around, we got together at Matt's place and put the songs together. Somebody would walk in with a guitar riff, and we'd get down to building it. Other times, people might have complete songs. But yeah, I'm completely involved in the process.

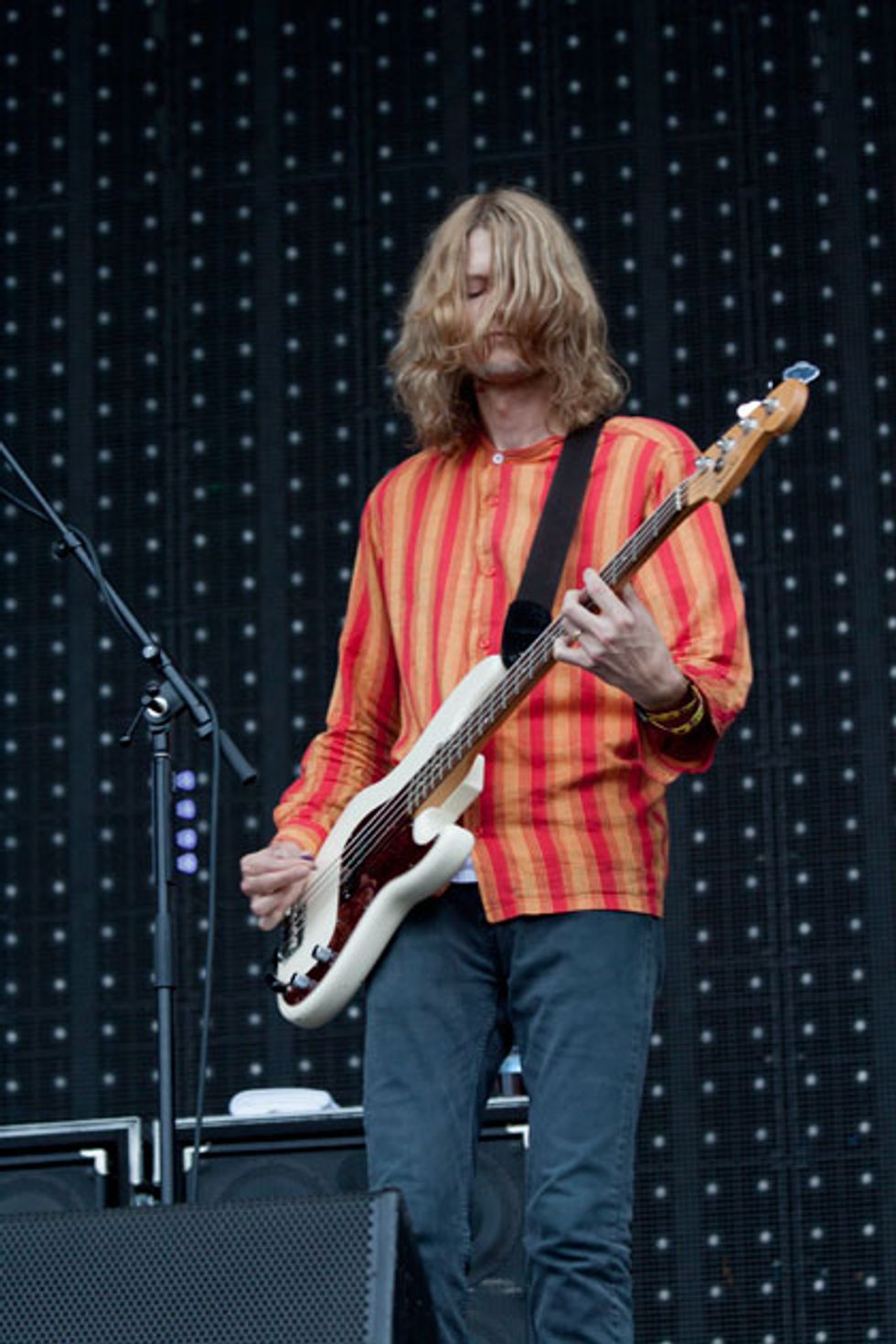

Bassist Daniel Tichenor nails the groove with his Fender American Standard Precision Bass on the Lollapalooza stage in 2014. In the studio, he relied on Auerbach's short-scale Fender Mustang for big sounds. Photo by Chris Kies

On your previous album, Melophobia, you shut yourselves off from a lot of recorded music to get away from influences. I'm guessing you listened to a lot of music, particularly older bands, when working on this album?

Shultz: Well, see, I think this album is really an extension of the last record and what we've always done. On Melophobia, we wanted to step back from our influences, which is sort of impossible because, like it or not, everything that you go through in life influences you in some way or another. We tried to let our own voice speak on Melophobia, for better or worse, and this record is the continuation of that in a different way. We're still going forward, even though we're not discarding songs because they sound like they could come from the '60s or whatever. We're not cutting ourselves off to anything.

Tichenor: I'm constantly influenced by music—new stuff, old stuff. I've tried to cut myself off from music, but I don't know … that's not my thing, really. I don't know if it's possible. I think you're always influenced by what you hear or what you've heard.

What kinds of musical ideas jumped out at you from listening to '60s acts?

Shultz: As a guitarist, the whole approach of going direct really appealed to me, and I got that from those bands. A lot of them did the exact same thing—went right into the console.

Brad Shultz's Gear

GuitarsFender '65 Mustang reissues

Gretsch G6139T White Falcon Double Cutaway

Gretsch G5422DC Electromatic 12-string

Fender Paramount PM-3 acoustic

Gretsch Chet Atkins Country Gentleman (studio)

Amps

Fender Twin Reverb combo

Fender Super-Sonic 60-watt head

Fender 2x12 cabinet

Effects

2—Voodoo Lab Pedal Power 2 Plus units

ZVEX Instant Lo-Fi Junky modulation/chorus/vibrato

2—ZVEX Mastotron fuzz pedals

Pigtronix Tremvelope envelope-modulated tremolo

JHS The Crayon distortion

Malekko Heavy Industry Vibrato

Malekko Heavy Industry Red, Dark, and Lofi Ekko 616 delays

Boss DD-7 digital delay

MXR Phase 100

SubDecay Spring Theory reverb

Boss TU-3

Radial J48 Active Direct Box

Strings and Picks

D'Addario ECG24 Chromes flatwound strings (.011–.050)

D'Addario EXL Nickel Wound 12-string 150 Regular Lights (.010–.046)

D'Addario EJ11 80/20 Bronze Acoustic Guitar Strings (.012–.053)

Dunlop Tortex .50 mm picks

Daniel Tichenor's Gear

BassesFender American Standard P Bass

Fender Mustang Bass

Fender Jaguar Bass

Gretsch White Falcon Bass

Amps

Fender Super Bassman 300-watt head

Fender Bassman 810 Pro Bass cab

Effects

Fulltone GT-500 distortion/boost

Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi

Strings and Picks

Fender Nickel-Plated Steel Taperwound bass strings (.045–.110)

Dunlop Tortex .88 mm picks

But I think the thing that influenced us the most about those bands was the separation of their tracks. When you sit and really listen to their recordings, you notice how each instrument is doing something very specific. Each part is so thought-out and placed so deliberately. I really drew from that.

When you go direct into the console, do you notice that you actually play differently than when you're going through an amp?

Shultz: Yeah. I think that's probably the appeal of it for me. It feels more human. When I hear that, I really hear the person playing, not so much this amp sound. The strings speak for themselves, almost, if that makes any sense. You can hear the pick actually hitting each individual string as you strum a chord, or you can hear each individual stroke of a lead part.

So that was really appealing to me, maybe because I'm such a raw player. I basically beat the shit out of a guitar. I'm very heavy-handed. I want to hear the separation between each string when I'm strumming a chord. You can hear that on this record, and I really like that. It gives the guitar sound a lot of personality.

Tichenor: Of course, I always go direct. But as far as the guitars, yeah, I think you get a more personal sound by going right into the console. There are not too many effects on the guitars; they're not tweaked around. You get a more raw and honest sound that way.

You both used some of Dan Auerbach's instruments. What brought that about?

Tichenor: Dan definitely wanted us to experiment a bit. I brought a few basses in, but Dan handed me his Mustang bass and was like, “Man, you've just got to use this one. The way it records is so sweet." It had a shorter scale neck than what I was used to, but I figured it out soon enough. I tried it on the first song and thought it sounded amazing, so I stuck with it. I think it made me play a little differently. It made me pull some of those older sounds out a bit easier.

Brad, you used a few of Dan's guitars. Which ones stuck out to you?

Shultz: My favorite guitar of Dan's that I used was an old Gretsch Chet Atkins Country Gentleman. Dan was on an episode of American Pickers, and the Gretsch he bought on the show is the one I played. It was pretty remarkable, really—just a great feel and sound.

Was it difficult getting used to that guitar? You've been a Mustang player for many years.

Shultz: No, I liked it right off. I think it has a fatter, warmer tone, and that's what some of the songs called for. I did use my '65 Mustang as well. Whatever the song called for is what I played. If we wanted a thin, bright sound, we'd go with my Mustang. If we wanted something a little fatter for some of the more fuzzed-out songs, we would use the Country Gentleman. A few times I used an old Kay. Dan had some of those old Japanese knockoffs. I tried some of those out, and they were pretty cool.

What about effects? Dan has a pretty amazing collection of pedals.

Shultz: I didn't really use any effects, other than maybe a reverb here and there. I have all kinds of crazy pedals, but I wasn't into them for this record. I wanted to see what it would sound like to just strip it all back to either clean or fuzz. If we wanted fuzz, we would just crank the console and make it really hot. Then, obviously, if we wanted a clean sound, we just took it back down and got a great clean direct sound.

There's some gargantuan fuzztone on the song “That's Right." How are you getting that sound?

Shultz: Oh, you know what? That's the only song I used a fuzz pedal on [laughs]. Sorry. We did crank up the console to the bone and got fuzzed up, but I also doubled that with a ZVEX Mastotron. Man, that's a really cool, awesome fuzz pedal. I like how it messes up the guitar sound and makes it sound like a horn.

You do a nice little guitar solo in that song. Too little, in fact. I wanted it to go on longer.

Shultz: I think that's the beauty of some of the shorter songs—you're left wanting a little bit more. Then you go back and listen to the track again, and you find different things within the track.

Surf's up! Guitarist Brad Shultz and his '65 Mustang reissue (which has been beaten so severely onstage that its body is glued together) get a lift during Lollapalooza 2014 in Chicago. Photo by Chris Kies

The bass is very dominant on the record, particularly on the song “Cry Baby." It kind of forms the musical bed much like Paul McCartney did on the Beatles' “Come Together."

Tichenor: That Mustang bass creates a big sound. That was new for me, for sure. I definitely try to write melodic bass lines, so maybe they just punch through more. Brad and I like to layer melodies. We like the guitar and bass to marry each other.

Shultz: Daniel is the MVP of the record, in my opinion. The bass lines are just ridiculous. Like I said, what I did on this record was to really strip back a lot of the unnecessary shit that we'd put on some other records. Get rid of the bells and whistles and you're left with that separation between the tracks I talked about, and that allows the bass to really come out because there's room for that. Nothing's getting in the way.

Brad, another great solo is at the end of “Cold Cold Cold." It's totally bruising, but it doesn't sound like a guitar. It sounds like a kazoo. That was all recorded direct?

Shultz: Yeah, but that was Nick, actually. He did that solo. I think he was using a WMD Geiger Counter. That's a fucking ripping fuzz pedal for you.

Do you guys jump ball for who does the solo, or does he just put his hand up and go, “I've got this one?"

Shultz: Honestly, we like the written kind of solo—one that's planned out. So it's not about, “Hey, let's get out there and play." We'll sit around, throw ideas out and shit like that. In the case of “Cold Cold Cold," I think that's probably the best solo on the record.

ready for anything." —Daniel Tichenor

The lead lines throughout “Portuguese Knife Fight" have a great '60s psychedelic sound. They almost sound like a Coral sitar.

Shultz: What are we doing there [pauses]? I don't know. It might just be the double effect of me and Nick playing at the same time. The song was written with just standard chords, and then we peeled it back to each of us playing single notes. It gets a cool effect like that.

Are you guys in the same room together? How does that work with you going direct?

Shultz: Oh, we cut in the same room, the whole band for the full record. Nick used an amp, but I'm going direct. It's cool. I can hear everything with my headphones on. We play like a band.

Do you woodshed before you record an album?

Shultz: [laughs] Nah. Honestly, I would like to think if you love music, you're playing music anyway and it's not a practice thing. I spend so much time trying to write songs, so I get my practicing in that way. So no, I don't really practice. I just play.

Tichenor: I like the element of surprise. We do like to be prepared before we go into the studio, but you need freshness and spontaneity. You want to be open to new ideas, but if you get too set on things, you might not come up with new stuff. It's a balance. You want to know what you're doing, but you want to be ready for anything.

YouTube It

Cage the Elephant channels '60s roots in this live performance of “Mess Around" from their latest album, Tell Me I'm Pretty, produced by Dan Auerbach. Augmented by touring members Nick Bockrath and Matthan Minster, they turn the song into a psychedelic rave-up on TV's The Late Late Show with James Corden in December 2015, with Bockrath rocking his signature model Harper Marilyn semi-hollowbody and Brad Shultz flogging his Gretsch double-cutaway White Falcon.

Is there anything in particular you still want to learn on your instruments?

Tichenor: I started out as a guitarist, so for me, playing the bass is still something I'm learning and getting better at. The bass is a whole different beast from the guitar. One thing that's pretty helpful for me is to study bassists from other bands. I love Paul McCartney. He writes such catchy melodies and bass lines. You listen to him and there's so much to absorb.

Shultz: I think my weakness is technical knowledge. I've always played by ear and I've gotten by pretty well. I can play the guitar, but I don't really know what the fuck I'm actually doing. I've always run away from studying music because I didn't want to mess up my style. When I first started playing, people would ask me how I got my thing down, and I'd say, “I basically taught myself and learned by ear." They'd be like, “Oh, don't ever take any lessons or learn anything. You'll fuck your whole thing up." But recently I feel as though I want to dig a little deeper and get a little knowledgeable about what I'm actually doing. You want to learn enough to take you further, to allow you to facilitate your ideas, but you don't want to lose that part of your personality that makes you unique. We'll see what happens with it.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)