Some guitar heroes explode across the stage or erupt from recordings. Think Hendrix or Jimmy Page. Others, like Colin Linden, have a quieter brilliance. They play to support fellow musicians and their own songs with a perfection that extends beyond service into art, dancing a characterful line between the sacred and the profane, the beguiling and the dramatic. They have a visionary approach, distilled from years of surveying their craft and shaping what they’ve learned into diamonds. And with those jewels they can refract complex emotions or simply cut like the patient, intuitive, and exacting badasses they are.

Linden, who has a wonderfully raucous and spacious new album called Blow, is a crucial ingredient in the glue of Nashville’s—and, therefore, the world’s—roots music scene. And while the ability to write songs that turn life into an open book, create sounds that wallow in the dirt or glide toward heaven, or illuminate the wisdom and heart in the work of those he supports or produces seems part of his DNA, it all traces back to a magical encounter with a giant.

By age 11, Linden was already a guitar prodigy. He’d seen Hendrix and other major performers of the day and had traced the rock he loved back to its blues roots. When he learned that his favorite artist, Howlin’ Wolf, was playing a matinee as part of a six-night stand at Toronto’s Colonial Tavern—just a bus ride away—he begged his mom to take him. “The show started at 3:30, but I was so eager to make sure we had no trouble getting in, we got there about three hours early,” Linden recounts. And there was Wolf, sitting on a staircase near the stage. Linden raced down to the 6'6", 300-pound bluesman and explained that he had to stay in the balcony due to his age, so wouldn’t Wolf come up to talk with him? “Of course,” Wolf growled, and their friendship blossomed and flourished for five years, until Wolf’s death in 1976.

Ain't No Shame

Wolf, who was a remarkable judge of character, saw something in the kid. “One of the things that he said—to an 11-year-old—is you got to do your best and you got to play the same if you’re playing for three people or if you're playing for 3,000,” says Linden. “I know that it’s kind of corny, but it does speak to the idea that the calling of being a musician is greater than the success you may achieve in a public sense. That idea is something that sustains you when you are playing for three people—and not just when you’re a 15-year-old kid, but when you’re 35 or 45 … or maybe 55. Being blessed to be able to make music is a wonderful calling, and I reflect on Wolf’s generation—and the earlier generation of musicians like Sam Chatmon and Son House—and think about what those people went through and yet still kept a sense of wonder about playing music.”

“Being blessed to be able to make music is a wonderful calling, and I reflect on Wolf’s generation—and the earlier generation of musicians like Sam Chatmon and Son House—and think about what those people went through and yet still kept a sense of wonder about playing music.”

That sense of wonder, and the engagement it engenders, has been at the core of a storied career—even if everyone doesn’t know Linden’s story. A year after meeting Wolf, Linden started playing coffeehouses and radio and TV shows, and began developing the deft fingerpicking that’s one of his signatures. Canadian blues guitarist David Wilcox became his slide guru, hired Linden as co-guitarist in his group, and gave him 140 blues albums he considered essential building blocks. “David showed me the possibilities of what was there,” Linden relates. “I already loved Elmore James, Fred McDowell, Robert Johnson, Blind Willie Johnson … that whole generation of great slide players. And I was aware of open D and open G, and some related tunings. David really showed me how to play ‘Terraplane Blues.’ I’ve spent the last 47 years still hearing him every time I play it, and almost every day I listen to some Robert Johnson, and every time I hear something I haven’t heard before. I keep digging deep into it. Of course, I loved roots music at the time, which had so many elements of blues in it: Ry Cooder, Little Feat with Lowell George, and I can’t underestimate the influence of David Lindley playing on the Jackson Browne records. I also loved all kinds of singer-songwriter music. The Band were always there for me, too. [The Band recorded Linden’s song “Remedy” on 1993’s Jericho.] Almost all the music I love was very informed by blues.”

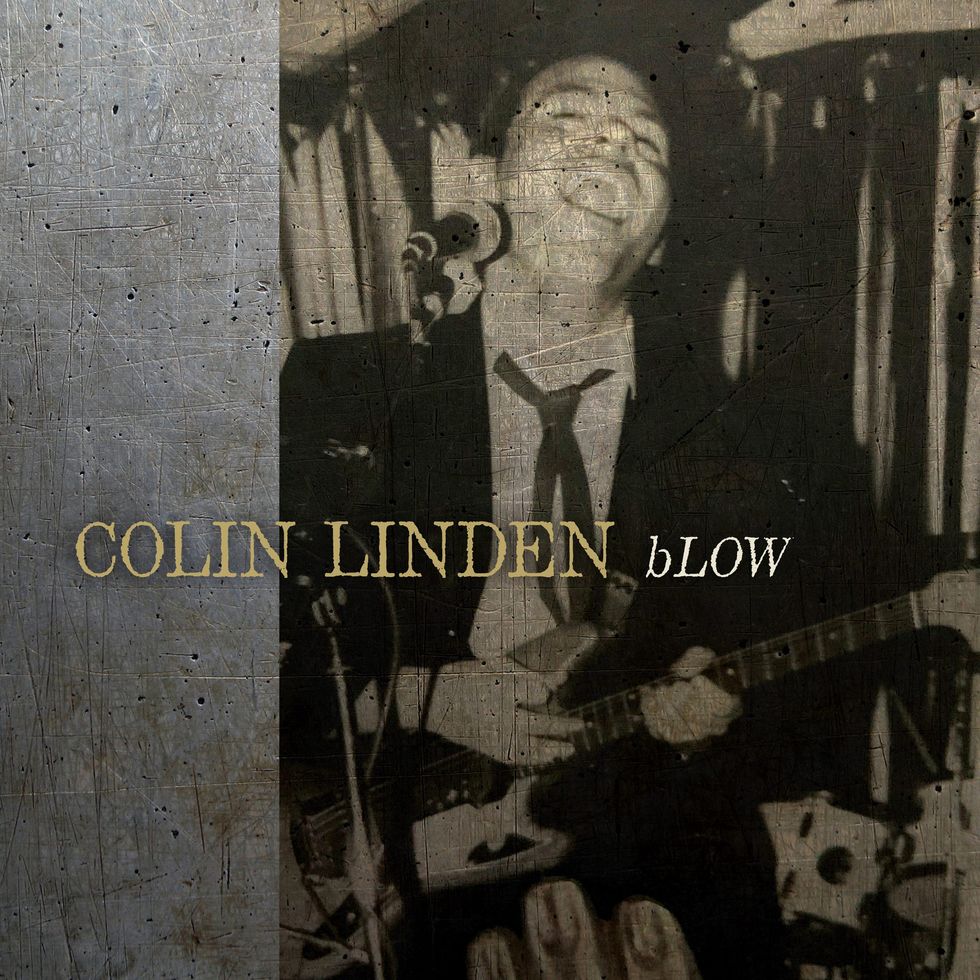

November 27, 1971—the fateful day that 11-year-old Colin Linden met and was befriended by his idol, blues legend Howlin’ Wolf, aka Chester Burnett.

Photo courtesy of Colin Linden

In 1979, Linden played his first recording sessions, for 80-year-old Mississippi Sheiks’ guitarist Sam Chatmon’s final album. His own debut, Colin Linden Live!, came a year later. Since then, Linden’s ridden the swells and shallows of the business, yet there’s always been a tide of albums, bands, and gigs to surf. In the ’90s, he played guitar and co-produced for legendary folk-rock artist Bruce Cockburn, and, since his move to Nashville in 1997, has produced albums by Keb’ Mo’, Paul Thorn, Colin James, Lindi Ortega, Eden Brent, Gina Sicilia, and a passel of other roots performers. He’s played gigs and recorded with many of the above as well as Emmylou Harris, Alison Krauss and Robert Plant, T Bone Burnett, John Prine, Gregg Allman, Rhiannon Giddens, the Pistol Annies, Buddy Guy, and Bob Dylan. (Linden’s 2013 summer tour with Dylan is his favorite: “All my life, he was the person I wanted to play with the most. I loved playing with him, I love the other guys in the band, and the crew. It was an absolutely unforgettable, wonderful experience.”)

In addition, Linden has made 11 albums with the heralded Americana trio Blackie and the Rodeo Kings, with fellow songwriters and friends Tom Wilson and Stephen Fearing, and has 14 solo albums under his belt. Along the way, he’s earned a Grammy and nine Juno Awards, several Maple Blues Awards, and dozens of other awards and nominations.

TIDBIT: In the vintage photo on the cover of his latest album, Linden is playing one of his first electric guitars: a 1964 Fender Mustang that was given to him on his 17th birthday by Canadian bluesman David Wilcox.

There’s even a good chance you’ve seen Linden and not known it. T Bone Burnett drafted him for the TV series Nashville a decade ago and he’s appeared onscreen many, many times as the ubiquitous guitarist in black—his everyday choice of monochrome. Off screen Linden’s served as the show’s bandleader, one of its key songwriters, music producer, and eventually music director during the series’ six years. He’s also been the music director for a series of U.S. and European tours featuring Nashville’s stars, and continues to perform and record with Charles Esten, who played the brilliant but troubled songwriter Deacon Claybourne.

Linden also has a track record on the big screen—not only as Father Scott, the singing preacher in the Coen Brothers’ rom-com Intolerable Cruelty, but as a soundtrack artist whose contributions include O Brother, Where Art Thou?, Everything’s Gone Green, Please Kill Mr. Know It All, and Inside Llewyn Davis.

Onstage, Linden effortlessly ricochets between original songs, traditional blues and gospel, and textural playing based in traditional roots music that reaches for the cosmic.

Photo by Art Tipaldi

His new album Blow ignited as a soundtrack project. Linden was asked to do stock music for Hap and Leonard, a dark TV buddy comedy about two rule-bending fixers-for-hire. “I kinda did it on spec,” he recounts. “I didn’t even pick the other musicians, but they were people I knew and admired very much: bassist Dave Jacques and drummer Paul Griffith. And we recorded with a fantastic engineer named Mark Rubel, over at Blackbird. It was very inspiring. Over the course of a couple days, I came up with maybe 18 pieces of stock music. And because the show was set in the Texas/Louisiana border area, I wanted to draw upon sounds that were kinda from there. I was so happy with the sounds that Mark got on my guitar, and so happy with the way it all turned out. Part of the deal was that I could take the tracks and use them for whatever purpose I wanted. And among those 18 pieces, maybe eight or nine felt like songs—just the structure that I’d improvised my way through.”

Sliding on a Truly Regal Regal

Linden’s most treasured guitar is this wonderfully voiced 1937 Regal Angelus, outfitted with both a gold-foil and a piezo pickup. Note his wrench-socket slide.

Photo by Ted Drozdowski

If you’ve seen Colin Linden onstage, you’ve likely heard him play his holy grail instrument, a 1937 Regal Angelus resonator guitar. It has a beautifully burnished natural tone, a bit lower and mellower than many resonators, and when Linden steps on a digital delay there are seemingly no limits on its ability to create honeyed textures that are transporting and transcendent.

The 5-pound wood-and-metal guitar with a solid, V-shaped neck is also perfect for his fingerstyle-with-slide approach. Linden says he keeps his slide, a no-foolin’ Mastercraft 5/8" socket, á la Lowell George’s 11/16", “on my finger almost all the time, no matter what I play, just cause I’m better at making certain notes sing with the slide than I am with my fingers. I’ll play a melody, and the first three notes of the melody will be the slide, and I’ll just go back and forth.

“Life changed tremendously for me when I got that 1937 Regal Angelus,” he continues. “It was gifted to me by [Canadian singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist] Linda McRae, whose first album I produced in 1997. She had that guitar at her apartment, and we were doing pre-production for the album, and I didn’t have an acoustic with me, so she said, ‘just play this.’ And it was the greatest guitar I had ever played. I asked her, when she was going to come to Toronto to record, ‘Would you mind bringing that guitar with you? I’d love to play it on your record.’ And she did, and I played it a ton on her record, and when the record was finished, she gave me that guitar.”

By then, Linden had been experimenting with combining acoustic and electric tones, including putting a piezo pickup and a magnetic pickup on the same acoustic guitar, “because there are elements of both of those things that I really value having.” He also uses heavy strings on all his guitars, “so the gauges were not a lot different between the electrics and acoustics for me. It was easy to go back and forth.”

One day, his luthier made him an offer: “I know you love gold-foil pickups. I have one that would fit right underneath the strings, and I can just affix it to the face with tape and see if you like it.” That gave Linden “a world of sound, and I put a McIntyre pickup on the cone. I eventually hardwired the magnetic pickup into the guitar, and that combination gives me a sound I love. I’ve played it, certainly, on over a hundred records. I’ve played that guitar with Bob Dylan, with Emmylou Harris, for President Obama at the White House. I played it at Carnegie Hall, the Ryman, Royal Albert Hall, Massey Hall in Toronto. That’s the guitar that comes with me everywhere.”

And here’s a fun fact. Linden’s worn a slide on his left-hand pinky so often and for so many years that his finger has permanently bent to accommodate it. That’s something he’s seen before. “When I was 15 years old, I met Tampa Red. He was living in a nursing home in Chicago, but me and my friend Doc MacLean visited him on a journey that we took to the Southern states. Doc was a few years older than me, so he could drive. Even though it had been many years since Red had played, his pinky was permanently extended and almost looked dislocated from the rest of his hand from all of his years of playing slide.”

Now Hear Colin and His Regal Regal

Drink deep in Colin Linden’s magical resonator tone as he performs a solo version of the title track from his 2015 album, Rich In Love, at Nashville’s 3rd & Lindsley.

During pandemic downtime, Linden got the itch. “I thought, ‘I’d like to make an album where this is the backbone, and I’ll add whatever songs need to come.’ I was feeling so creative. As with a lot of other songwriters I know, I ended up being on fire writing, just ’cause we weren’t out playing and stuff. So, I finished those songs and wrote a bunch of others and co-wrote a few new ones. It was an interesting process for me, because some of those pieces were just a few bars that I’d loop and build a song around.”

Colin Linden’s Gear

Linden’s No. 1 amp: a cat-scratched 1957 Fender Deluxe that he’s nicknamed the Pig. “I bought it for $175 when I got off the road with Leon Redbone, out of somebody’s garage in Berkeley,” he says.

Photo by Ted Drozdowski

Guitars

- 1937 Regal Angelus with DeArmond Gold Foil and McIntyre pickups

- Various Fender Telecasters

- 1963 Fender Stratocaster

- 1952 Gibson Les Paul

- Gibson Custom Shop Les Paul goldtop

- Harmony Stratotone

- Nash T-style with Bigsby

- National Resolectric

- 1951 Gibson CF-100 E

- 1966 Gibson B-25-12

- Martin 000-18

Amps

- 1957 Fender Deluxe called “the Pig”

- 1954 vintage 5A3-circuit Fender Deluxes

- Fender Deluxe tweed and ’65 reissues

- Analog Outfitters Sarge

Strings & Slide

- D’Addario (.012–.014–.016–.030–.040–.050)

- D’Addario flatwounds (.011–.053)

- John Pearse Phosphor Bronze Lights (.012–.053) for the Regal

- Martin Mediums (.013–.056)

- Mastercraft 5/8" socket

Effects

- Line 6 M9 Stompbox Modeler

- Xotic EP Booster

- Analog Alien Rumble Seat Overdrive/Delay/Reverb

- Fulltone Custom Shop Tube Tape Echo

- Fender Reverb Tank

- Boss DD-5 Digital Delay

For the most part, he worked alone in his backyard home studio in a quiet Nashville neighborhood, just 10 minutes from the Ryman Auditorium, one of TV-Nashville’s real-life locations. Maybe that solitude is why he was able to crawl so deeply into his guts and give Blow a raw, personal sound. It’s raucous tones and mostly hard-boiled arrangements sound as if they were cultivated in a sweaty juke joint or a swamp-side roadhouse rather than a studio. It might also help that he was joined by some old friends: a host of Fender Deluxes (including a ’57 named “the Pig” that’s had much of its tweed shredded by a nonetheless beloved cat) that he sometimes runs in stereo, a Nash T-style, a flock of Fender Teles (including a ’71 re-fin that gets him into Robbie Robertson’s tone zone), his Gibson Custom Shop goldtop Les Paul and another from 1952, a 1963 Fender Stratocaster, a Harmony Stratotone, several acoustics, and the crown jewel of his extensive guitar collection—a 1937 Regal resonator with a voice that’s pure emotional Esperanto. (See sidebar.)

Blow’s 11 songs also sound like the past rushing toward the future. Linden’s writing is focused and poetic, whether celebrating love in the Wolf-flavored stomper “Angel Next to Me” or diving into the urban demimonde in “Until the Heat Leaves Town,” which includes a guttural, dark, and wobbly slide solo that slouches toward the avant-garde but fits the song perfectly. That’s a one-two punch he first encountered hearing Hubert Sumlin push the envelope with Howlin’ Wolf. Linden’s guitar tones are full of muscle and blood and skin and bone, with their rawness often drawn into relief via modernist mixing techniques, like pushing the drums to the fore in “4 Cars” and in the soaring slow blues “Change Don’t Come Without Pain,” where flourishes of drunken bent notes and slide, and rotary and octave effects, plunge into psychedelia with mad abandon. On the trad side again, “Boogie Let Me Be” sounds borrowed from John Lee Hooker’s ’40s/’50s catalog, and “Right Shoe Wrong Foot” is about as Bo Diddley as even Bo Diddley ever got, with Linden’s guitar dealing out a reverb-drenched, 3-2 clave-fueled beat.

“Almost all the music I love was very informed by blues.”

“I kind of went with what made me happy,” Linden says. “My ear for sounds and my own aesthetic of mixing records is so informed by my heroes, Chess Records, Sun Studios, and the great Excello recordings, so that’s what I go for. It makes me smile when I hear that stuff. But I’ve also worked with T Bone Burnett a lot, ever since he produced an album for Bruce Cockburn called Nothing but a Burning Light in 1991. I love how T Bone transports something timeless and otherworldly into something that’s immediate. It’s so appealing. He’s had such a gigantic impact on my life.”

Linden’s fingerpicking on Blow is also a joy, allowing him to literally dig into licks and make his guitars’ strings snap and howl, layer rhythm lines with melodic counterpoint, and shift seamlessly between slide, chords, and single notes. “I was 13 and had been performing for a year or more when a couple people told me, ‘If you wanna learn country blues, you should maybe learn how to fingerpick. Those guys are fingerpickers,” he recalls. Older artists, like Ken and Chris Whiteley from the Toronto folk scene, became his mentors, and then working with Wilcox was his master class. “When he got me into combining slide and fingerstyle, it made me feel like there were no limits,” Linden says. “He was and is a wonderful improviser, with an incredible imagination, and he’s gifted in a lot of genres. After that, fingerpicking really was it for me. And then, I realized that a lot of stuff I wanted to play—like Steve Cropper licks—would really sound better with a pick. So, I started to use one when I formed my first band at 17. Then I got into hybrid picking. But fingerpicking is really where I feel at home. It’s like breathing.”

Another instrument that appears on Blow is this 1963 Fender Stratocaster, which is a recent acquisition. Note the interior of the slide, revealing its identity as a socket wrench.

Photo by Ted Drozdowski

Like the committed artist he is, Linden constantly works to evolve his playing and his tonal palette. “Over the years, that’s really meant focusing on the fundamentals,” he says. “It’s having better time, playing more in tune, and being more economical. I’ve learned so much from so many of the great guitarists here in Nashville … people like Richard Bennett. [Mark Knopfler’s longtime sparring partner and a session and studio ace.] I got the chance to do a few sessions with Richard. He’s a hero of mine, and he would play a Telecaster through a Deluxe Reverb, and I’d have my pedalboard and I’d have everything on. I’d do everything that I could to get the greatest sound, and it would sound maybe 25 percent as good as him just playing guitar into an amplifier. He served the song always, in a really focused and committed way. So, the things that I’ve learned from my heroes, like that, continue to be drummed into me. I got a chance over the last few years to play on the Grand Ole Opry a lot of times, and I would see the guys who were in the Opry band, especially Jim Capps, who was the sweetest guy, and Kerry Marks. They were always serving the song and they would be very economical, but put fire in it, too.

“When you’re touring a lot, your chops have to be in great shape,” Linden continues. “Even here in town, when I’m playing with Whitey Johnson”—the parodic blues persona of songwriter Gary Nicholson—“I’m taking maybe 30 solos a night. During the pandemic, I felt like that part of my life, which had been a constant for 40 years, became … well, it was gone. And not only did I crave it, but I wondered if I was playing as well as I should or could. I noticed that on a couple albums I played on and produced, I put so much effort into making every note as emotional as possible, playing with as much soul and fire as I can. I mean, I can practice Blind Blake and Charley Patton and all the stuff I do really well, but you can’t really simulate being a soloist in front of a big crowd. So, you focus on something different in your playing and hopefully the good things about you that you keep close will all be there when you get back to playing live. That’s what I’m hoping for. [Laughs.] I’ll let you know.”

YouTube It

Colin Linden plays his 1937 Regal Angelus on his dream gig, supporting Bob Dylan. Here, Linden’s fingerpicking and slide provide the backbone for Dylan’s tribute to Delta blues legend Charley Patton.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)