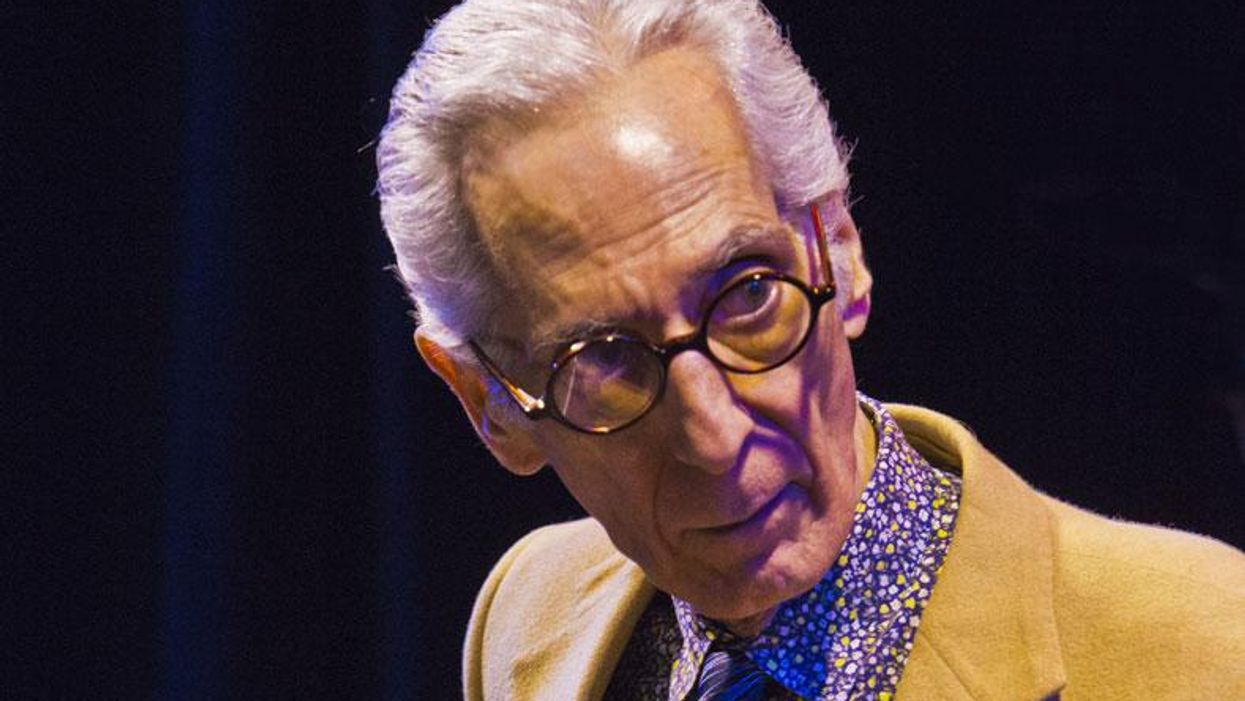

“It's simply a toy." That's how Pat Martino describes the guitar. For many, he's the father of modern jazz guitar whose pioneering approach has influenced generations of players. But to Martino, picking up his instrument is akin to making morning coffee. He views the guitar as a coffee pot, something that once you know how to use, you stop thinking about. “The guitar has become a significant member of the family," says Martino from his Philadelphia home. “Whenever I need that experience I go back to it, and it fulfills me, and that's all I've ever asked it to do."

This “toy" has led Martino, who recently turned 73, to become one of the most influential jazz guitarists in the world—twice. He released El Hombre, his debut album as a leader, in 1967. It solidified Martino's reputation as a fleet-fingered bebopper who could find his voice within the bluesy soul of an organ trio. Leading up to this recording, he'd spent his 20s apprenticing with such B-3 heavyweights as Don Patterson, Jack McDuff, and the under-appreciated Trudy Pitts (who is featured on El Hombre).

During the late '60s and early '70s, Martino's albums became more experimental as he wove Indian influences (Baiyina), 12-string explorations (Desperado), and more electric instrumentation (Consciousness) into his music. That was when one of Martino's tunes crept into a jam session Joe Satriani had organized with a few friends. “I remember the chords," says Satriani, who at the time was deep into blues and rock, yet looking for something to expand his consciousness. “Specifically, it had to do with two chords. He just moved the voicing up while the bass note was the same, but it sounded perfect. We could never handle the 'bad' notes like he could handle them."

In 1996, things came full circle when Satriani was asked to play on Martino's All Sides Now album, which was tracked at Michael Hedges studio. Satriani was tasked with bringing in a few sketches, and as the guitarists were preparing to explore one of these sketches, Martino busted into Satriani's signature hit, “Satch Boogie." “It totally blew me away," remembers Satriani. “Hearing it that way was eye-opening because I always imagined that song with a horn section."

In the late '70s, Martino began experiencing seizures with increasing frequency. This led to a diagnosis of arteriovenous malformation (AVM), a disease that required several brain surgeries. The price Martino paid to preserve his health was severe. In addition to losing some of his memory, Martino lost his ability to play guitar. During this time, he moved back in with his parents, and his father would play El Hombre, Strings! (Martino's second solo album), and other recordings by his son to help him remember who he used to be.

In his 2011 autobiography, Here and Now!, Martino describes the long journey back to playing guitar. “The ability to play the guitar was always there but was latent. It came down to wanting to use it, to give it significance. It's like the guitar said to me, 'What do you want to do with me?'"

Martino's facility slowly came back and led to The Return, a trio album recorded live at Fat Tuesday's with bassist Steve LaSpina and drummer Joey Baron. “I haven't listened to it since it came out," says Martino.

On his first studio album in 11 years, Martino augments his core organ trio with trumpet and saxophone. “I was looking for added texture," he explains. “It's been a wonderful experience."

At this point, Martino has more years of playing under his belt than he did before the musical amnesia. His latest album, Formidable, is just that. Surrounded by his working trio of fiery organist Pat Bianchi and drummer Carmen Intorre Jr., Martino expanded his musical palette by adding saxophonist Adam Niewood and trumpeter Alex Norris. The result, like everything Martino plays, is rooted in the blues and is dripping with the sounds of those organ groups he cut his teeth with in Philly. His trademark attack and buoyant dark tone are everywhere, and his tributes to Mingus (“Duke Ellington's Sound of Love") and Duke Ellington (“In a Sentimental Mood") are as heartfelt and meaningful as anything he's recorded in a decade.

PG caught up with Martino after his yearly hometown Thanksgiving residency to discuss his complex thoughts on music, how he views the fretboard, and why you should always rock a 4x12 cabinet—as long as you don't have to carry it.

It has been over 50 years since El Hombre. After many decades of releasing records, does the feeling of getting new music out into the world change at all?

No, it hasn't. There's something about the process that is repetitive in terms of what must be done and how it must be done. It just unfolds with a specific identity: the personnel, organizing personnel, and choosing the material, which has a great deal to do with those personnel.

You've made the organ trio your home, so to speak. Yet for Formidable, you chose to include saxophone and trumpet. Did the material dictate that choice or were you looking for added texture?

I was looking for added texture. The availability of some great players, and just looking for a change, had a great deal to do with it. Adam [Niewood] and Alex [Norris] were brought to my attention by several people, including Pat Bianchi, the organist, who was familiar with both. And so too was Carmen Intorre. I was impressed and I thought it would really be a great move to go out as a quintet, and it's been a wonderful experience.

Martino routinely gigs with a 4x12 cab—a rarity for jazz 6-stringers. Photo by R.R. Jones

How did “El Hombre" come back into consideration?

I wanted to hear it with two horns and Pat was very wired up about that particular composition. He did some of the arrangements and it just felt great.

When you were originally writing that tune, had the thought of an expanded texture crossed your mind?

At the time it was originally recorded, which I believe was 1967, it had a great deal to do with the personnel, specifically [organist] Trudy Pitts. We had been playing together quite a bit during that time and there was just this great feel, this rapport that we both got interactively.

Although you never got a chance to work with Gerry Niewood, you did record “Homage," which was his tribute to John Coltrane.

The only version of that I knew about was recorded by Adam, in honor of his dad. I had heard that and I was impressed—it was a great recording. The fact that he wrote it about Coltrane didn't really affect me becauseidentity is something that is personal, it is original, so that didn't really extend into Gerry's initial intentions.

Listening to Coltrane's later work, I can hear the pain and emotions he was going through. How do you convey to a listener the essential feelings that are behind your music?

I think it's conveyed through authenticity. It's conveyed through the enjoyment and the commitment that the individual prevails upon the instrument that he or she has chosen. It's hard to say why these things take place, they are just so honest and so rich with artistic commitment that it's a phenomenon more than a business or a profession. I think that it was that way with Coltrane, and it is that way with many artists, like [pianist] Gonzalo Rubalcaba or [saxophonist] Wayne Shorter. It's what we do that does us as well.

Joey Calderazzo's “El Niño" was an interesting choice. It's quite different from the version on Michael Brecker's Two Blocks from the Edge.

Actually, I had never heard that recording of it. I first came across the tune when Joey and I were performing duets sometime back, and that's one of the songs we played. I wanted to hear it with horns.

You've had several signature guitars over the years, and right now it seems your signature Benedetto is your main guitar. What do you look for in terms of an instrument?

I think the general element is accuracy. It's an instrument that's in tune. It's an instrument that can be altered with regard to its tensions. It's an instrument's appearance—a number of things. It's not any specific company, I take that upon myself when the time comes. I adjust to an instrument, and more than anything, I will be honest to you, is when I'm in a situation where my guitar doesn't show up. I get to the gig and I have to use somebody else's guitar. Something's delivered, and to be honest with you it's a piece of shit, but I've got to use it [laughs].

Guitars

Benedetto Pat Martino Signature Model

Amps

Various Acoustic Image heads

Mesa/Boogie or Marshall 4x12 closed-back cabs

Raezer's Edge cabs

Effects

None

Strings and Picks

GHS (.016–.018–.026–.032–.042–.052)

The challenge of the moment is such a rewarding experience that it neutralizes the loss, or the entrapment, in one object—my guitar. I then get involved in a completely different challenge than trying to get the instrument back because now I am on the gig, and there is no time to worry about something that isn't there. These are some of the things that I think about when it comes to the instrument.

What type of amps are you using now?

I use an Acoustic Image. Over 20 years ago, Buster Williams, the bassist, turned me on to it, and I've never looked back. I got involved with Rick Jones, one of the owners of Acoustic Image, and they provide everything. If I need an amp, I just give him a call. It's just a wonderful relationship. The amps are six pounds or less, and they go up to 600 watts. Just amazing.

For the last few years, you've been using a full-size 4x12 cab. That's an unusual choice for a jazz guitarist.

That came about when it became available without having to carry it. It's on my contract rider. The only thing I carry in is my six-pound Acoustic Image, and the sound of it is exquisite if it's a good cabinet. The gamble is that you get what's delivered by the management, and they sometimes send in bad cabinets. They've been used, let's say, by loud rock players and they're damaged in the process, so there is always that gamble. I'll be honest with you, the majority of the time they come in really great, so I take advantage of it.

When you're at home what kind of cabinets do you use?

I've got a series of Raezer's Edge speaker cabinets that were originally given to me by Richard Raezer, who passed away sometime back.He used to come over to the house, and he would provide the speaker cabinets. He gave me a whole series of them and he even put my name on them. I've got various sizes, but the largest one that I've got is a 1x12.

I've seen you do many clinics over the years, and one theme that you often touch on is how the guitar is simply a toy. Are there certain things you do or practice that keep that symbiotic relationship going?

I think it's not what I do, it's what I choose not to do. I am affected by what I hear and what I'm exposed to and that's an ongoing flexibility. There's always something that causes the excitement of wanting to experience it for the first time, and I am led back into that and that's one of the beauties of the instrument. It's a wonderful experience. Like I said, it's a toy, and it's very flexible and because of that, the guitar offers endless possibilities.

“Most guitarists have learned pianistically by using the scales and the modes, but I didn't learn that way," says Martino.

“I get involved in the magic of the instrument." Photo by R.R. Jones

I recently spoke with Joe Satriani about his experience on your All Sides Now album. He told me he was amazed at your ability to seemingly make the “wrong" notes sound right.

That's interesting. There is consonance and there is dissonance. What gives them the spirit they contain, what gives them importance is motion, and motion has no sound. Motion is what manipulates those elements, and when I get involved in motion like that it makes no difference where it's going, because while it's in motion you can't hear. There are no right or wrong notes. It's when an idea resolves that the magic conveys.

As an active educator, you've written and produced quite a few instructional books and videos. Was the idea of passing along the craft instilled in you when you were younger?

Not so much for me personally because I think the majority of individuals that flourish within that particular reality are musicians in general. It's the way he or she learned. Most guitarists have learned pianistically by using the scales and the modes, but I didn't learn that way. I learned in exactly the same way I continue to learn now, from the magic that's imbued in the matrix. The guitar is a matrix, though there are certain things that take place that in most cases are never studied by guitarists.

Can you give me an example?

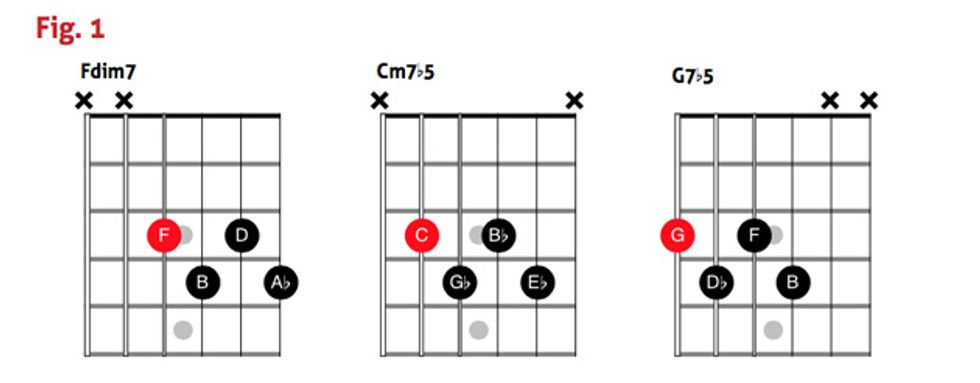

Sure. If you take the upper four strings and play an F°7 chord at the 3rd fret, you get F–B–D–Ab (Fig. 1). I've learned that when you take that shape and you keep the same fingering and you move it to the next inner set of strings, you get a Cm7b5. Now take that same configuration and move it to the lowest strings, it's now a G7b5. Those three inversions came from physical conditions, not from music.

You're more focused on how that shape moves across the neck instead of looking at four individual notes and how they move around.

Exactly. The same thing would happen if I play a G7 on the lowest four strings at the 3rd fret (Fig. 2). If I move that to the next set, it's now a Cm7. If I move that to the next string set, it's now an Fm6.

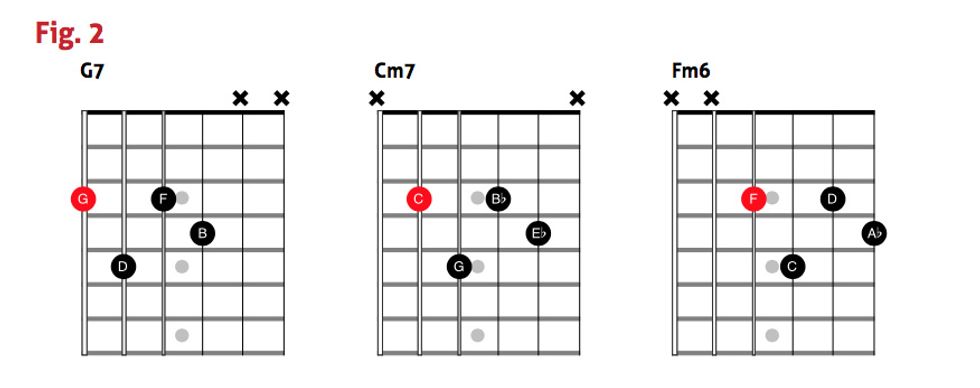

I know you center a lot of fretboard ideas around the augmented triad. How does it factor into this concept you're describing?

If I were to take an augmented triad, let's say it's C–E–Ab (G#) at the 8th fret (Fig. 3). If I move that to the next string set, it's now an F augmented (F–A–C#) triad. On the next string set, it's a Bb major triad and then an Ebm triad. The instrument itself unveils these different phenomena without the need for a teacher.

You spent time with a rather legendary Philadelphia guitarist, Dennis Sandole, who also taught Coltrane, Michael Brecker, Jim Hall, and others. At that age, what was he able to clarify for you?

I really did not have any interest in Dennis' method, but I had to qualify, to have an interest for interacting with him. I didn't study his music as much as I studied him, that's why I went there. I went there to study him, his appearance, his surroundings. I studied the artwork that he followed. I studied many things about him, and I learned a lot. At the time, I was also studying his students, who included John Coltrane, James Moody, Benny Golson, McCoy Tyner, and Philly Joe Jones. I really didn't need to study music. That seemingly was innate within me as a child.

Your educational materials often have an artistic, visual flair. Where did the geometric aspect of how the guitar functions come from?

I think more than anything it came from my interest in learning enough about music that I could function socially with musicians. As far as the source of the information that I gained through my approach, there had to be a translation of it into something that was viable, in terms of interacting with serious musicians. So, it moved along those paths and it always remain second to what it was used for. When I have a student come in, I don't teach them music because I am not a music teacher. I give them the opportunity to see how I function and I share those formulas with them and hope that they can reach a point of interaction that's productive for them. I don't get involved in the root, the third, the fifth, and the seventh and the alterations. I get involved in the magic of the instrument and how everything automatically inverts itself with no musicality whatsoever.

The phenomenon of an augmented triad is double sided, like a coin has heads and tails. This phenomenon also has major and minor, light and dark. It's a study of opposites more than it's a study of music. Music is only used as a universal language, so when students come to me the first thing that I convey is that I'm not a musician. I'm studying the magic of this. It's closer to sorcery than it is to music.

Probably the closest thing Pat Martino has had to a hit is his recording of Bobby Hebb's “Sunny," which first appeared on Pat Martino/Live! At 2:54 in this live trio performance, Martino reels off a repetitive open-string phrase that snakes its way through the entire tune.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)