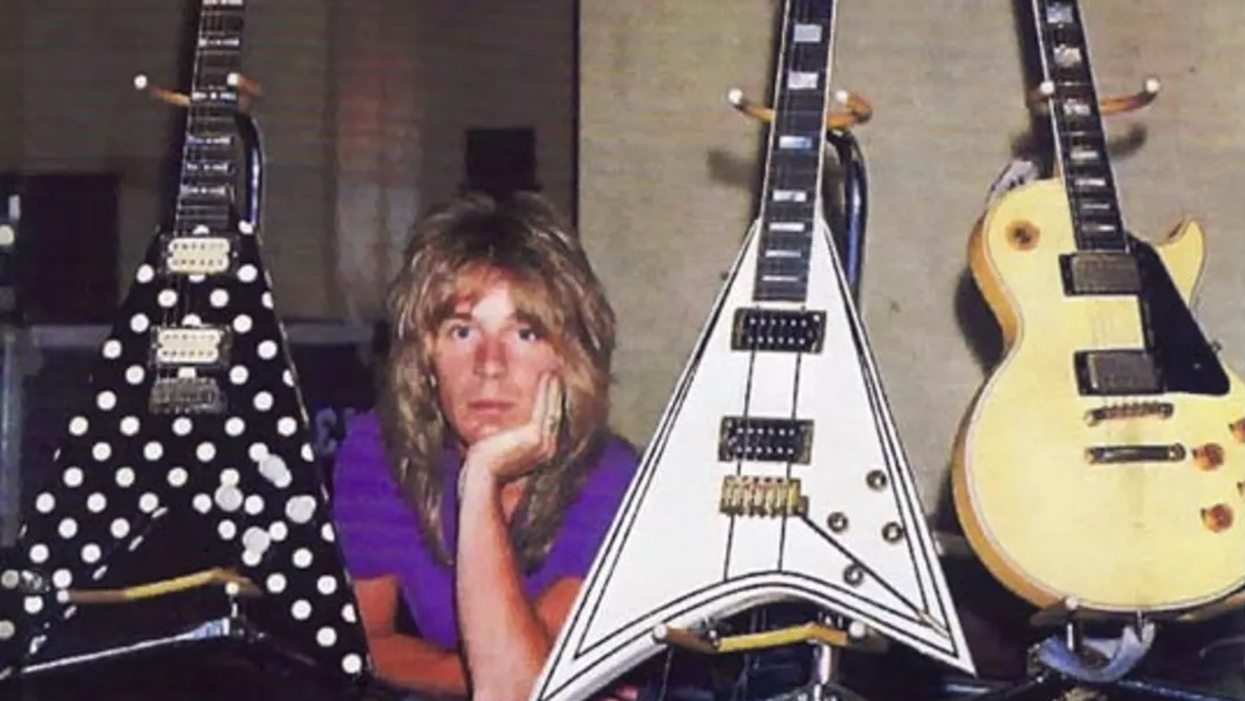

As Randy dazzled the guitar community with his playing, many guitarists remained curious about the tools of his trade. Randy's main guitar was a Gibson Les Paul Custom, which was flanked by two unique V-shaped guitars. While much has been written about these guitars, most observations have simply scratched the surface. With the help of luthiers Karl Sandoval and Grover Jackson, we revisit these very special guitars of Randy Rhoads.

Randy Rhoads began his performing career playing a cream-colored Gibson Les Paul Custom. His Quiet Riot bandmates had acquired it collectively for Randy's sole use in the late seventies. Initially, Randy thought it was made in 1963, but would later discover it was actually made in 1972. This revelation came from John "JT" Thomas, an avid Gibson collector and guitarist for the British band Budgie, who opened during Rhoads' first European tour with Ozzy. The Les Paul was Randy's main guitar throughout his career and he used it for a majority of his recordings and performances with Osbourne.

The Les Paul Custom, per 1972 spec, had a four-piece body: two layers of mahogany with a thin layer of maple in the middle and a carved maple top. It was white when new, but the nitrocellulose lacquer yellowed over time. It was also heavier than fifties era Les Paul Customs. Randy made only a few cosmetic alterations to the guitar, replacing the brass toggle switchplate and substituting the Grover tuning machines with Schallers. The most noticeable marking on this guitar was Randy's name engraved on the pickguard. Pickups during this era of construction were Gibson-produced "T-Buckers," named for the T-shaped tool marking made in the forward bobbin of the pickup.

An Idea for a New Guitar

Before joining up with Ozzy Osbourne for Blizzard of Ozz, Randy was still slugging it out on the L.A. scene, playing shows with Quiet Riot. In 1979, Randy found himself gigging with another local guitarist he admired from the band Xciter, George Lynch, who would later come to fame in Dokken. In those days, the two often conversed about technique, amps and, of course, guitars. One particular evening, Lynch showed up with a new single-pickup V-shaped guitar. Randy was excited to see it and asked to check it out. The guitar had a flat radius fretboard and a tremolo bar on the body, something uncommon on V-shaped guitars at the time. To Randy, it was like two worlds colliding—a Gibson-inspired shape with a Fender-made mechanism. Lynch had had the guitar custom-made by a local luthier named Karl Sandoval. As Randy was fascinated by the design of this guitar, George urged him to give Karl a call.

Karl Sandoval began his career as a luthier while playing guitar in the band Smokehouse. He was on the same scene that included many of Randy Rhoads's contemporaries, like Eddie Van Halen and George Lynch. He built relationships with other guitar players on the basis of his guitar playing and the amazing guitars he made for himself. He had been working with Wayne Charvel at the Charvel guitar shop when he received a call from the Quiet Riot guitarist. He recalls that first conversation with Rhoads, saying, "I remember Randy giving me a call, telling me that he was backstage with George doing a show and got to play the guitar I made for George."

On his first visit with Sandoval, Randy discussed ideas for his own version of what he had seen on George Lynch's V. That was July 3, 1979.

"I can remember that day," Sandoval says, "walking around in my garage discussing this guitar ... talking about the headstock, the color, the bowtie inlay on the neck. He wanted the Les Paul's double humbuckers and the Fender Strat tremolo. He also asked about putting the toggle switch and the output jack on the upper wing." Randy also mentioned that he did not want a bolt-on neck because he wanted the guitar to have the playability of a Gibson.

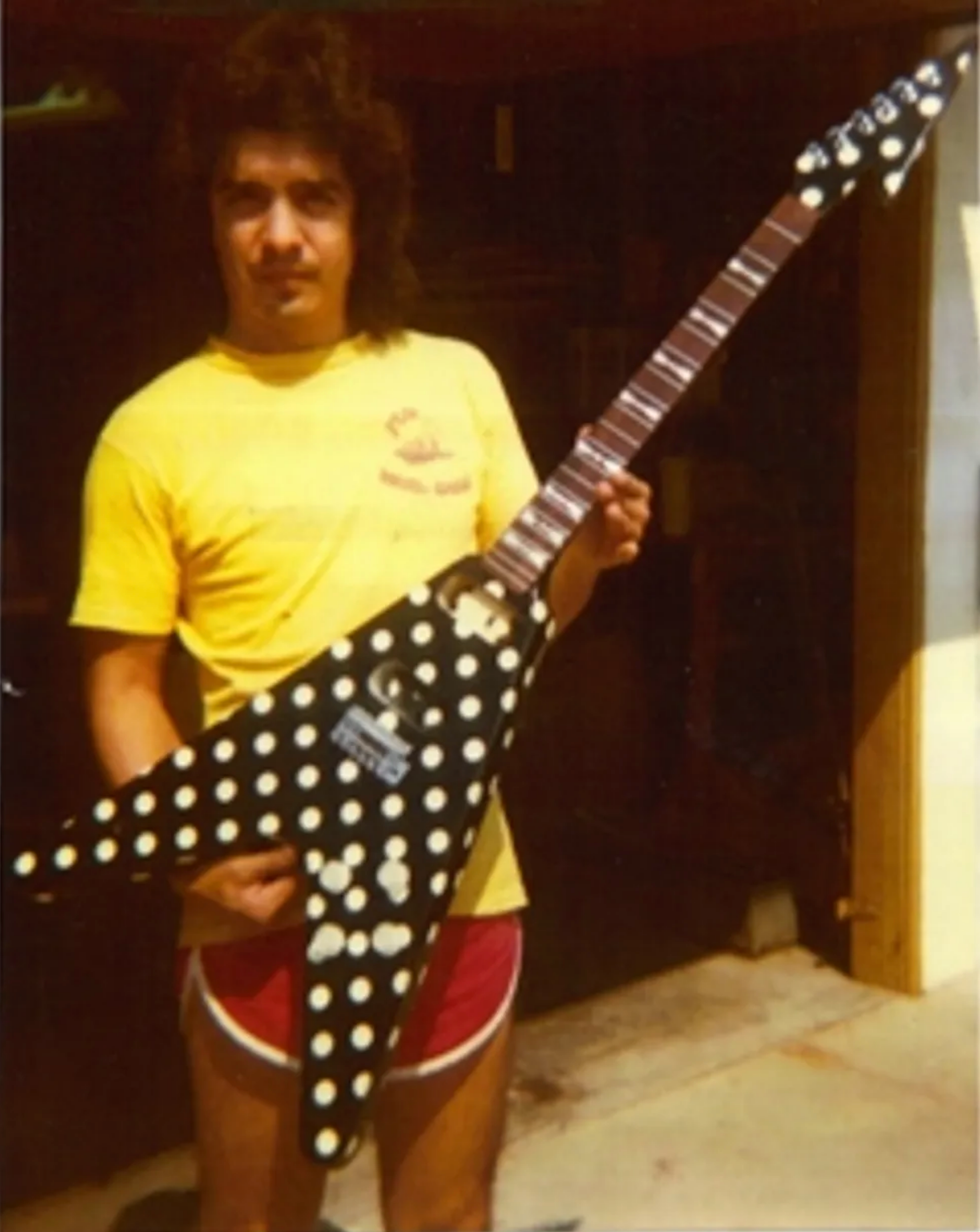

Sandoval with Rhoads'' in-progress first V.

As Sandoval tells the story, "I talked with Randy about coming up with something different in a guitar, a different look, saying, 'Let's come up with a different headstock, a different color, come up with an identity.' And then he started to tell me, 'V body with polka dots' ...honestly, I thought that was hideous but then I just kinda used my imagination." Randy wanted 3/4" dots painted all over the guitar, and to give it perspective, he didn't want them randomly placed on the guitar.

"I took his ideas and I put them all together," Sandoval continues. "I was real good at putting guitars together in my head. I could visualize the guitar in my head before it's even started. He didn't want a bolt-on, so the neck is set into the body."

Building a New V

The first step in building this guitar was finding a Danelectro neck. Sandoval had become accustomed to using these necks, and they were a central feature of his guitars, but he still had to hunt one down: "I would go to swap meets and pawn shops a lot. Back in the day, I was picking up Silvertones and Danelectros for like 15 to 25 bucks. I couldn't even get necks from wholesalers for that price! Basically I took them off the guitars and I ended up with a lot of guitar bodies and no necks."

Contrary to popular belief, these necks did have truss rods. As Sandoval describes them, "It's two I-beam, non-adjustable truss rods glued into the neck before the fretboard is glued on. If you look at the end of these necks, you'll see two slots. That's where these on-edge I-beam truss rods are. It's like an inch-thick steel that will not bend. And it makes a maple neck very heavy. I think that's what contributed to the sound of Randy's guitar. There's a lot of metal there."

Because Randy wanted a Gibson sound, the two-piece body was constructed out of mahogany. But unlike a traditional Gibson-made Flying V, this body had to be much thicker to accommodate the depth needed for the Fender tremolo bridge sustain block.

"I had to tell him that it's going to be thick because 1 3/4" is the size of the block on the bridge," says Sandoval. "A Strat body is anywhere from 1 5/8" to 1 3/4". An original Gibson Flying V isn't that thick." Control cavities would be placed on the upper wing for the pickup selector switch and on the outside edge of the upper wing for the output jack. Having cut the body out, the next procedure was attaching the Danelectro neck to it.

Sandoval hit upon a unique way to position the neck and glue it to the body that incorporated the surrounding support: "I came up with a very simple neck pocket glue-in system. I have an extension of the neck underneath the existing neck where the neck pocket is and you shape the body around the neck. There's actually more wood that extends out and supports the neck. It's a square neck going into a square neck pocket, but you've got a lot of surface area when you clamp it with wood glue. It will never break."

Routing for the pickups presented a minor problem because the string spacing of the Gibson-style bridge position pickup was narrower than the width of the Fender tremolo bridge. As Sandoval states, "It's a good thing that you have a flux circle magnetic field underneath the strings." The pickups used on this guitar were a DiMarzio Super Distortion in the bridge position, and a PAF in the neck position. The electronics were similar to Gibson specs: two volume and two tone controls located on the bottom wing of the guitar.

When Randy and Karl drew up the design of this guitar, they also came up with a headstock design that was shaped like a harpoon or an arrowhead. Using the existing Danelectro headstock, Sandoval attached wood to either side, creating a paddle that the new shape could be drawn onto.

"I left the existing headstock on and doweled the sides to graft on pieces of wood," explains Sandoval. "Then the correct shape was cut out."

Rhoads with his Sandoval V.

Photo by David Plastik

When Randy and Karl drew up the design of this guitar, they also came up with a headstock design that was shaped like a harpoon or an arrowhead. Using the existing Danelectro headstock, Sandoval attached wood to either side, creating a paddle that the new shape could be drawn onto."I left the existing headstock on and doweled the sides to graft on pieces of wood," explains Sandoval. "Then the correct shape was cut out."

The outcome of these elements was a Flying V shaped guitar made by Karl Sandoval but based on Randy Rhoads's ideas. The guitar had a scale length of 25 1/2", a 17" radius neck, and was finished in nitrocellulose lacquer. Although it is not widely known, Randy actually broke the headstock off the guitar only three weeks after it was built.

"He was devastated," Sandoval remarks. "I remember that call." As Randy described it, he was standing with the guitar when the strap came loose. The guitar fell and crashed to the floor, neck first. When Randy brought the guitar back to Sandoval, it wasn't as bad as it looked, but it was still a major wreck. "When the neck broke," he remembers, "it shattered down the middle. It blew out ... I saw multiple fibers of the wood sticking out on the neck part."

Sandoval continues: "He was more concerned about my work and what I had done, and he felt like he ruined my work. But I took it in and charged him another $75. I repaired it and it came out as good as new." The damage proved a testament to the strength of the neck pocket and of the neck itself, because the guitar did not break at the area where the neck joins the body. Guitars that take a similar fall will normally break somewhere in the middle or at the neck joint. Randy's guitar was repaired and little could be seen of the damage.

Randy Rhoads's Sandoval V guitar, a hybrid of a Gibson and a Fender, was completed in September 1979. Soon after that, Randy would leave his band Quiet Riot, having been tapped to play in Ozzy Osbourne's new band. Sandoval's creation headed overseas to England and a tour through Europe in 1980, and scores of Europress photographers snapped shots of it. In December of that year, Randy flew home to the states for Christmas. It was on that flight that he came up with an idea for a new guitar. He couldn't wait to get it built.

A Second V Takes Shape

Around the same time, Wayne Charvel sold the San Dimas, California workshop to a prospective new business partner, Grover Jackson. With Wayne gone, Karl Sandoval left to continue developing his company, Sandoval Engineering. This is what led Randy to call Grover Jackson about making his new guitar.

On December 23, 1980, Randy went to the San Dimas production facility to meet with Grover Jackson, the new head of the Charvel Manufacturing at that time. The Charvel factory was empty, since all of the employees had gone for the week of the Christmas holidays. Jackson sat in his office awaiting Randy's arrival. He recalls, "We sat there from noon until midnight and just talked about everything in the world. He brought a little scrap of paper that had four to five line drawings, saying, 'This is kinda what I want this guitar to look like.' We scribbled and made more drawings and he left."

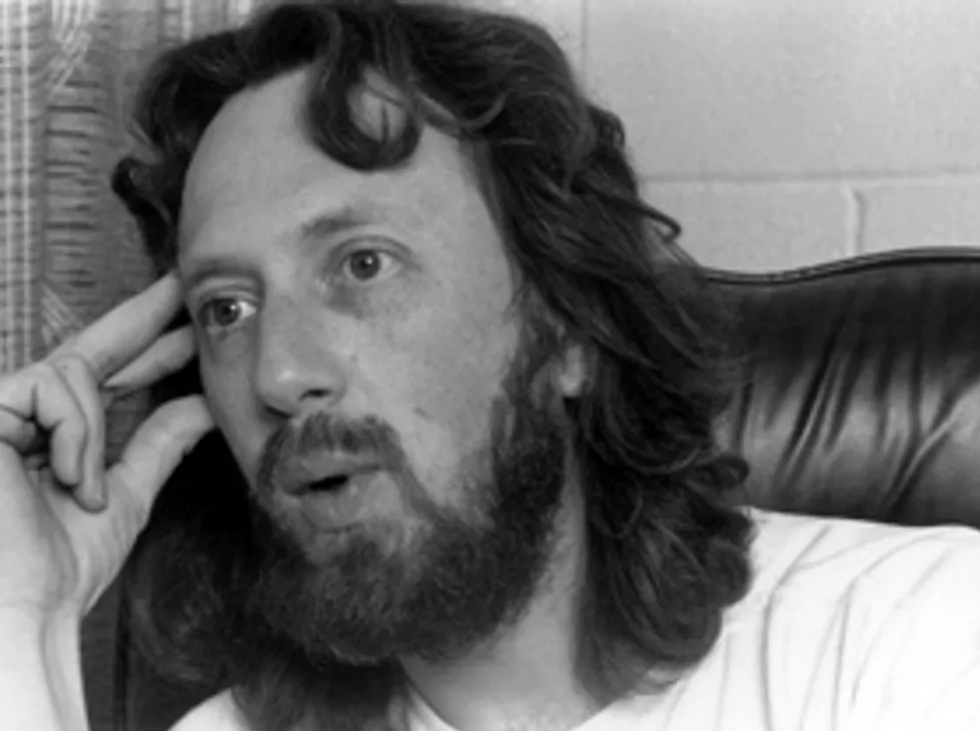

Grover Jackson circa 1980.

Those line drawings featured an asymmetrical V-shaped guitar body, with the bottom wing shorter than the top. It was to have pinstripes and, like the Sandoval V, a neck-thru-body design, rather than a bolt-on neck. During this marathon conversation, Randy told Jackson he had already chosen a name for the guitar: The Concorde.

According to Jackson, Ozzy and Sharon (then Arden) had bought him a ticket on the Concorde to come home to the United States, and that's where he came up with the name. From a marketing point of view, Jackson was concerned about the general look of the guitar and how the company's name should be presented.

"Charvel, at the time, was producing bolt-on, Fender-style guitars. Well, here's this crazy batwing thing, and I was afraid that might dampen the sales of the Charvels," Jackson reveals, "so I asked Randy if he would mind if we put a different name on this instrument, because we were going to create this new thing that was not like the other stuff. So it was also out of fear that I didn't want to piss on what we already had going on."

The final detail to be sketched out was the headstock shape. In time, that shape would become the company's trademark.

"Randy had that body shape drawing and it needed something that sort of matched it in radical-ness," Jackson explains. "So I came up with the head. I had been a vintage guitar guy and was always a Gibson Explorer fan. I wondered what I could do to an Explorer head to make it more modern and aggressive looking. Randy and I sketched around that idea and came up with the head, which later became a trademark." Charvel began making the guitar a few days after Christmas and Randy went back to England after the holidays.

The line drawings turned into reality when Jackson transferred them to a piece of Baltic birch.

"We band-sawed it to shape and then sanded it as best we could to use that as a template on a pin router to cut out the body," recalls Jackson. "It was real Cro-Magnon stuff." That template went through quite a few edits so they'd only have to cut the body once. Jackson remembers the sculpting of the guitar as being prehistoric in technique when compared to today's production standards: "The body was screwed to the template and then run around the pin router. This was pre-vacuum fixtures and pre-toggle clamps. And then it was sanded and sent to the paint shop."

Jackson says he added the beveled edges while carving the body: "I was making some BC Rich Bich's right about that time for my friend Bernie Rico. Those had beveled edges and I added the beveled edges to the Rhoads body. I ripped off my buddy! I'm being honest, okay?"

Jackson continued work on this guitar with Charvel's woodshop foreman, Tim Wilson, who did all the woodworking at the factory. As Wilson remembers, this was going to be a big guitar.

"The whole center block was solid maple," he explains. "The wings were also maple. It was a big hunk of tree. This thing was going to weigh a ton."

The end result was a very pronounced V-shaped guitar with a lot of surface area. The neck joined the body at the 14th fret, and it featured 22 frets on a compound radius ebony fretboard with pearl block inlay and binding. The frets were Dunlop 6230s, which is considered a small fretwire in comparison to Gibson frets. This was basically Dunlop's version of Fender fretwire.

Wilson recalls how certain things were done by hand back then that would be considered obsolete by today's standards: "Compound radius makes the surface of the fretboard flatter as you move up the neck, which goes from 12" to 16" in radius. We shaped that by hand. The neck shape was thick, somewhat like a fifties-era Gibson Les Paul, which is what Randy specified, and it was 25 1/2" in scale."

And, like a Gibson, the nut width was 1 11/16". In contrast to the Sandoval V, this time Randy's aim was to have a guitar that had a Gibson sound and Fender playability. Like the Sandoval V, it also had a tremolo bridge. Made by metalsmith Bill Gerein for Charvel, this bridge was a production standard on many Charvel guitars at the time. It was made of brass with a heavy brass sustain block.

Also like the Sandoval V, it had two volume and two tone controls. The pickups were a Seymour Duncan Distortion at the bridge, and a Jazz model in the neck positions, both mounted to the body with solid brass pickup bezels, also made by Gerein. The selector switch was located along the outer edge of the upper wing of the guitar. The output jack was placed on the outside edge of the lower wing, where the V shape converges. It was painted white with black pinstripes, undercoated with polyester and finished in polyurethane. And, as Tim Wilson had predicted, it was a very heavy guitar.

Redesign for the Concorde

The first version of the Rhoads Concorde guitar was completed in late February or early March of 1981, and it was shipped to Randy in Europe. Randy would report back to Jackson that he was having trouble reaching the upper register frets. He was also concerned with public perception of the guitar, since fans were asking him if he'd cut up a Gibson Flying V. Approaching Jackson for another guitar, Rhoads wanted to have a second one made that was more radical, with a narrower V shape so that it would be more original looking; so people wouldn't think he'd butchered a Gibson.

"One of the things that wasn't cool was the guitar was just too big," Wilson is quick to point out. "The body shape was just too big and it was made out of maple, so it weighed a ton."

In October of 1981, Randy and Grover Jackson got together once again to scribble, draw and debate the design of another guitar. Jackson had prepared three neck-thru-body guitar blanks with headstocks on them; the wings or sides of the body were just blank pieces of material. He placed one on a table while Randy looked on.

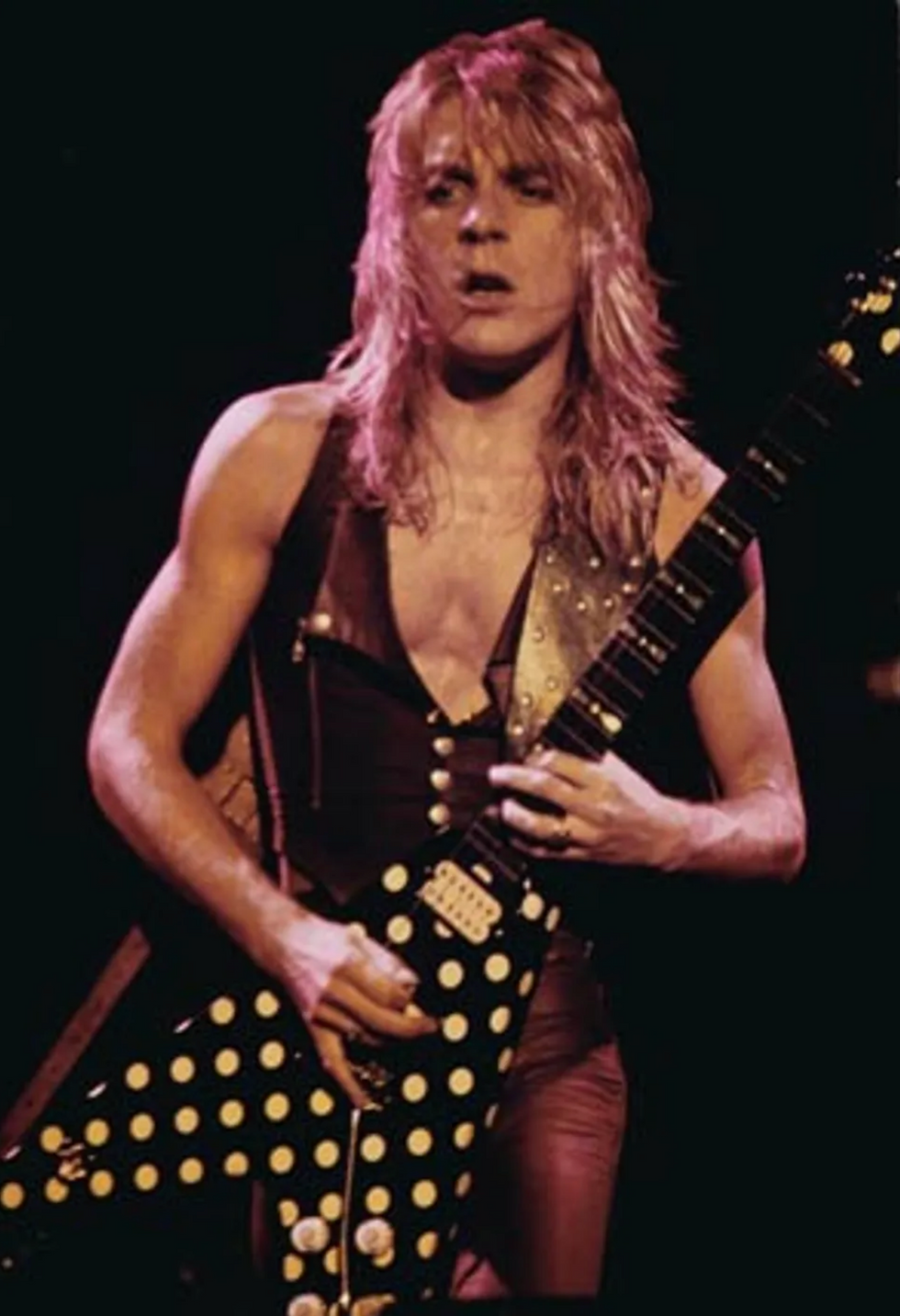

Rhoads playing the second Concorde shortly before his death.

"We stood over a workbench and drew for several hours ... drew on the blanks, erased it, sanded it off and drew some more ... more here, less there, and finally Randy said, 'That's it'," remembers Jackson. With the crude pencil drawing on this piece of wood, Jackson took it to the bandsaw and carved the body, a procedure that Randy could not stand to watch. Laughingly, Jackson admits, "Some guys want to know about the mechanics like car guys would be. And some guys want to know none of that, and Randy was one of those guys. He couldn't watch me cut it on a bandsaw."

By the end of the day, Jackson had shaped the wood according to the pencil drawings and handed it to Randy so he could hold it and see how it felt and what it would look like. Having done that, he began planning the building process while Randy went off to begin the first leg of the 1981 Diary Of A Madman tour with Ozzy overseas.

By the time the tour landed in the US a couple of months later, manager Sharon Arden had built the Ozzy Osbourne show up to major headline status by investing in full production staging, lighting and tour staff. Full stage rehearsals were conducted at Francis Ford Coppola's Zoetrope studios in Hollywood before everyone headed to San Francisco to begin the tour. Meanwhile, in his San Dimas factory, Jackson had the second guitar built and completed. He delivered it to Randy on December 27 during the final rehearsals at Zoetrope. This version of the guitar had a much more distinctive shorter lower wing, making the upper wing much more pronounced.

"It had a simple elegance to it," says Jackson. Clearly, this was not a hacked-up Gibson Flying V.

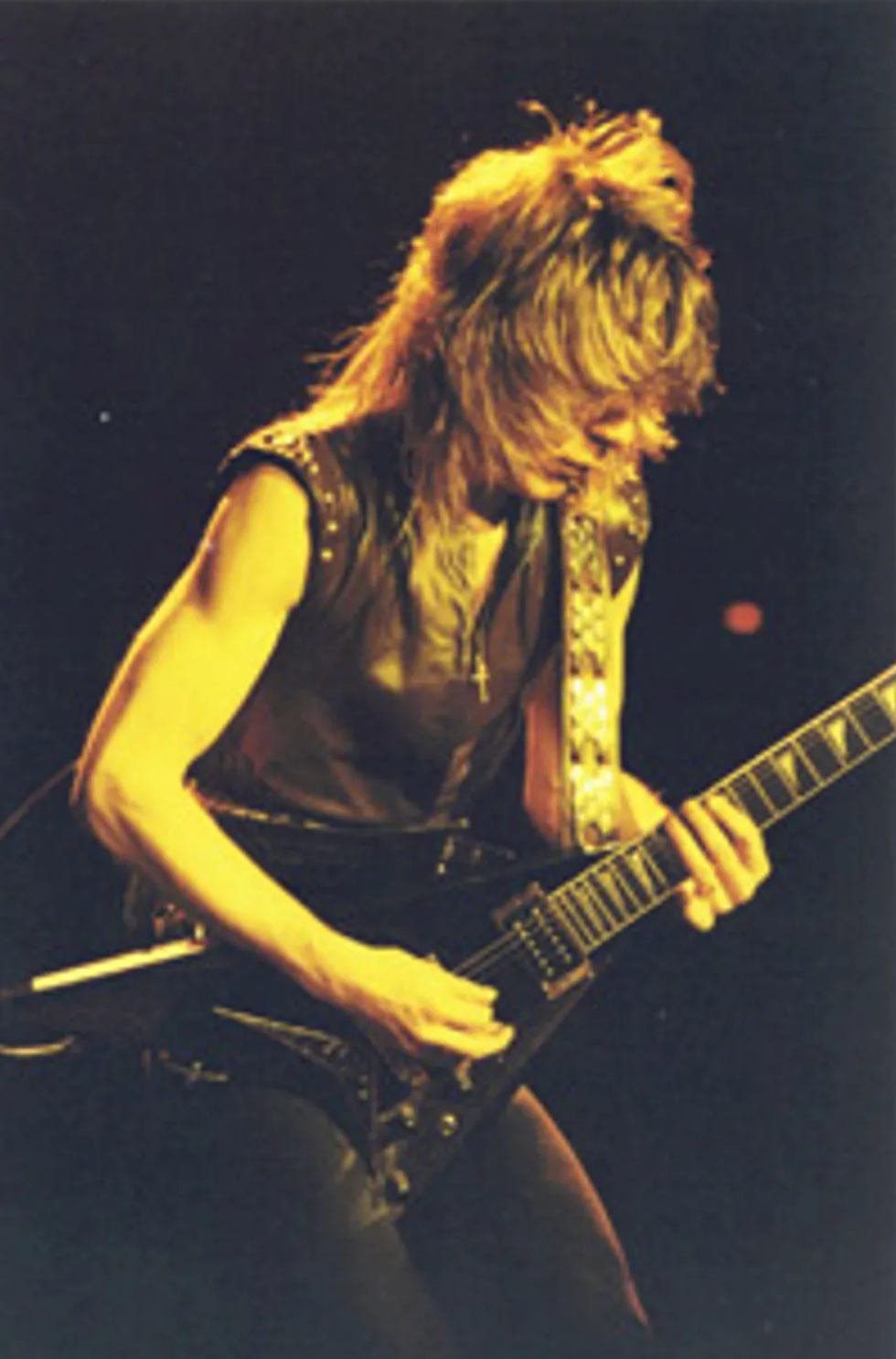

Jackson with one of his latest projects.

Despite the success of the guitar's redesign, Randy seemed a little hesitant to dive into it. Jackson offers some insight, saying, "A strange little quirk about Randy in my memory—and other people might dispute this—Randy was superstitious about guitars. I made a guitar for Jeff Beck one time and he just took the guitar onstage and played it in front of thousands of people. Randy was the opposite of that. Boy, he wanted to look at the guitar and then put it away. The next day, he'd pick it up, hold it, put it down and he'd go away. And a few days later, he'd pick it up and he'd play it a little bit and then he'd put it away. He had to kind of get synced up to it. He was playing the guitar by the time he passed away. There are pictures of him playing it, but he didn't play it the whole show. It wasn't the only guitar he played, and he was warming up to it. I think he was happy with it."

Two and a half months later, Randy Rhoads was killed in a plane crash. He was dead at the age of 25. His death still echoes within those who knew him. Fans around the world were just discovering his fantastic guitar style, and then suddenly he was gone. Grover Jackson, who had just stepped off a plane himself to visit a girlfriend in Reno, received the news while he was still at the gate. He is quick to admit he was, "Stunned ... and I'm still stunned."

Jackson says he owes a large portion of the success of his company to Randy. In fact, "... a huge amount ... an unbelievable amount is owed to Randy." Today, Jackson manufactures motorcycle, medical and musical instrument parts. Reminiscing about his days with the Jackson/Charvel Guitar Company, he says, "I saw the company as a toolmaker. There were these guys that had a job, which happened to be playing guitar. We were trying to be a toolmaker for guys doing work."

Karl Sandoval in his southern California workshop.

As for Karl Sandoval, hearing of Randy's death is still a fresh memory: "I remember I was in my shop and one of my friends called. He said Randy Rhoads had been killed. I turned the radio on and sure enough, they were talking about it. It was something like how a local rockstar was tragically killed in a plane crash. I was sad and felt bad because he was so young."

In the years since, Sandoval has expanded his guitar manufacturing business to include a guitar building school in southern California. For more information, visit his website at karlsandoval.com.

The man who did much of the woodwork on the white pinstriped V guitar made for Randy, Tim Wilson, holds the experience in very high regard. He would later become Jackson Guitars' general manager, and he built the company into a major player in the guitar manufacturing game.

Retired and living in southern California, Wilson says in retrospect, "I thought it was just going to be a big hit. I really did, and I really thought we were onto something. If things went our way, we were going to be pretty big. So, I was pretty proud of it, and I'm still proud of it to this day. It's one of the proudest moments of my life, having the honor of working on that guitar."

[Updated 11/4/21]

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Shop Scott's Rig

Shop Scott's Rig

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Zach loves his Sovtek Mig 60 head, which he plays through a cab he built himself at a pipe-organ shop in Denver. Every glue joint is lined with thin leather for maximum air tightness, and it’s stocked with Celestion G12M Greenback speakers.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.