South London artist Miles Romans-Hopcraft works under the moniker Wu-Lu. His pseudonym is a play on the Amharic word for water, wuha, but modified to avoid confusion with the Busta Rhymes track, “Woo-Hah!! Got You All in Check.” It’s a fitting handle, too, in that, like water, it’s indicative of Wu-Lu’s form-fitting, genre-fluid adaptability.

Romans-Hopcraft lives at the intersection of hip-hop, free improv, and grunge—imagine a Frankensteinian mashup of DJ Shadow and Slipknot, but looser—and crafts songs built from the lo-fi samples he rips from his extensive personal archive of tapes, mostly of open-ended jam sessions, that he then uploads to an Akai MPC sampler and drum machine.

South London—the triangle of Brixton, New Cross, and Lewisham, which sits south of the touristy city center along the River Thames—looms large in Romans-Hopcraft’s world. Owing, in part, its musical pedigree to the Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance located a stone’s throw from the New Cross Gate tube station, the neighborhood is the epicenter of the city’s vibrant and bustling new music scene. It’s also Romans-Hopcraft’s home turf.

Wu-Lu - South (Official Video) ft. Lex Amor

“It just happened that everyone happened to be in Lewisham somehow,” he says, marveling at the near miracle of growing up in the right place at the right time. “I went to the studio, and I saw Nubya Garcia [critically acclaimed saxophonist and bandleader], Joe Armon-Jones [keyboardist for Ezra Collective, Nubya Garcia], and Oscar Jerome [solo artist] up there, and I was like, ‘What are you lot doing up here? My grandma lives here, and my auntie lives around the corner. That’s why I’m here.’ Lewisham is a far part of South London to be in, but people are here because it’s cheap to live. Before my generation came through, there was a whole instrumental scene in South London with bands like United Vibrations, Polar Bear, and Acoustic Ladyland. A lot of people outside of South London started taking notice of what was going on and a lot of it gets coined as the ‘South London Jazz Scene,’ but the way I see it, it’s just instrumental music: people using their talent to be able to improvise in a feeling that they have.”

Romans-Hopcraft’s rich musical background is more than a matter of just living in the right neighborhood. His father is trumpeter Robin Hopcraft (most recently a member of Soothsayers, but with an extensive history playing Afrobeat, reggae, and jazz), and he’s also got an identical twin brother, Ben, who’s an accomplished artist as well (formerly Childhood, and now Insecure Men, Warmduscher, and something in the works under Sean Lennon’s direction). Plus, he’s closely associated with a coterie of artists like songwriter and guitarist Lianne La Havas, saxophonist Garcia, Black Midi drummer Morgan Simpson, and many others.

“A lot of people outside of South London started taking notice of what was going on and a lot of it gets coined as the ‘South London Jazz Scene,’ but the way I see it, it’s just instrumental music: people using their talent to be able to improvise in a feeling that they have.”

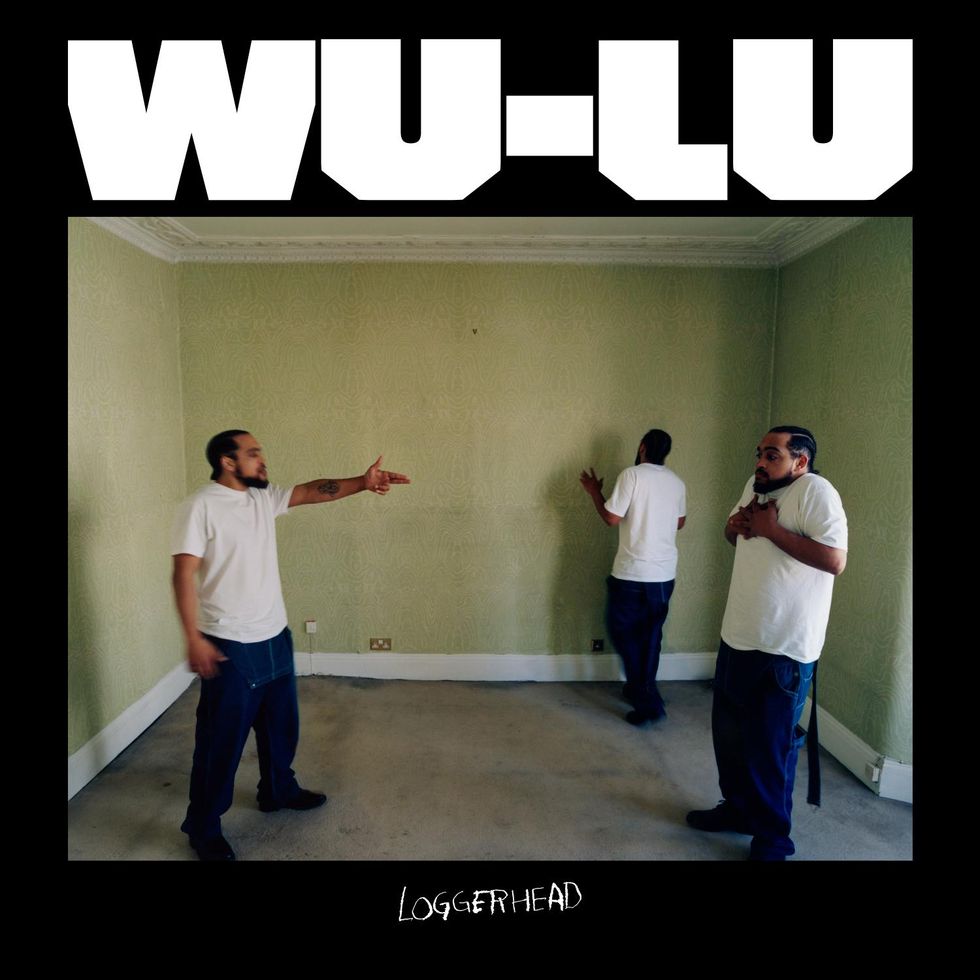

LOGGERHEAD, Romans-Hopcraft’s full-length debut, is an amalgamation of his experiences and aesthetic. “South,” the album’s lead single, is a slow crescendo that layers an acoustic guitar, raw hip-hop groove, and dub-style vocals before finally exploding at the chorus with a bloodcurdling scream (and featuring an outro rap from Lex Amor). “Times,” featuring Simpson, could, at points—both texturally and, maybe, because the Big Muff features so prominent—be at home on a Dinosaur Jr. record, if not for the tight, groove-centric drumming. And the eerie and melodic “Broken Homes” is a nuanced showcase for Wu-Lu’s songcraft, although, again, buried under layers of feedback and noise.

The whole album is like that. Intense, overwhelming, and constructed from scratch through an arduous process of scrolling through files and tapes, finding bits—be those inspired jams or someone dropping a cymbal—and then, slowly, honing those into complete, evocative, emotional masterworks.

“It might not even be part of a song,” Romans-Hopcraft elaborates about his crate-digging approach to samples. “It might be a drum break, or it might be something that was recorded on the wrong mic. It might be that I was playing guitar, ran into the control room, fiddled around, and when I listened to it later, discovered that when I put down my guitar, I was touching the guitar mic—and that would then become a whole inspiration for a completely different song. I can probably still go back into all those jams and pick out different stuff and make different music from that.”

Wu-Lu’s debut album is intense, overwhelming, and constructed from scratch through an arduous process of scrolling through files and tapes, finding bits—be those inspired jams or someone dropping a cymbal—and then, slowly, honing those into complete, evocative, emotional masterworks.

For example, the aforementioned “Times” started out as a birthday jam session with Simpson. “We were playing some beats—I was playing along with him—and someone in another room was filming us on their phone and sent me the video,” he says. “I heard this little ‘weee-weee’ sound and I was like, ‘That would be a sick idea.’ Morgan was playing something similar to what that was. I listened to that video intently. I programmed a drum beat on my MPC that I thought would work, built up a whole track, and eventually decided to re-record it [with Morgan]. On that tune I played all the guitars, the bass, all the synthesizers, and everything apart from the drums. But I programmed that beat beforehand. I told Morgan, ‘This is what I want you to play, but obviously add your feel to it.’”

Sampling your personal archives has other benefits as well. “Like avoiding royalties,” Romans-Hopcraft says, maybe slightly tongue-in-cheek … but only slightly. “I once asked about using a sample for something on a mixtape and they quoted some crazy, crazy price. I was like, ‘No more of this,’ and I started sampling myself. Plus, I like being able to look through stuff. The track ‘Blame’ came from being in the studio, doing long late-night jam sessions, and then having a few hours of jams I needed to look through to see what I could pick out. I sampled things, pulled stuff out of it, and then started remixing and overdubbing.”

Wu-Lu’s Gear List

Wu-Lu often builds his compositions around an initial sample from his own jam sessions, but the feeling from that original jam session is key to the song’s final form—even live.

Effects

- Electro-Harmonix Big Muff Pi

- JOYO JF-01 Vintage Overdrive

- Electro-Harmonix Stereo Memory Man with Hazarai

- Electro-Harmonix The Worm (wah/phaser/vibrato/tremolo)

- Boss RV-6 Reverb

Strings & Picks

- Rotosound Strings (.011–.048)

- Dunlop Tortex Green Picks .88 mm

But that freeform, loose, experimental approach ends once the song is completed. When it comes to reinterpreting those tracks live, Romans-Hopcraft plays what’s on the record. “I stick pretty loyal to the recording,” he says. “The live band setup is drums, bass, two guitars, and vocals—everyone’s on vocals—and also another drummer, but his kit isn’t a traditional drum kit. It’s like an MPC with loads of samples taken from the songs. For example, if we’re playing ‘Blame,’ that’ll be a drum break from the original track that I sliced into pieces where he can play the samples like a drum kit. It’s the original sounds, but he can play it.”

Romans-Hopcraft’s production techniques may be sample-centric and high tech, but he creates his music with inexpensive instruments and tools. “All my stuff is basically from car boot sales,” he says. A car boot sale is an English yard sale (“car boot” is British slang for “trunk”), and he’s amassed a bevy of inexpensive amps, old-school synths, and multitrack tape machines.

“All my stuff is basically from car boot sales.”

He favors Fender-style guitars, and their bolt-on necks and distinctive jangle is central to Wu-Lu’s sound. He runs them through a thick layer of fuzz, and, at times, will divvy that up between multiple amps. “I got a headphone splitter and plugged my output into that and then split my signal into like three different amps,” he says. “But the main thing I use is the Big Muff and this mini green pedal—a JOYO Tube Screamer-like pedal—that I got on Amazon for £15, which is like a high-gain pedal.”

But, more than anything, Romans-Hopcraft’s music is about the vibe. A composition may be a studio creation built up from an initial sample, but, even many iterations later, the mood from that original jam session is key.

“It might be that I was playing guitar, ran into the control room, fiddled around, and when I listened to it later, discovered that when I put down my guitar, I was touching the guitar mic—and that would then become a whole inspiration for a completely different song,” Wu-Lu says.

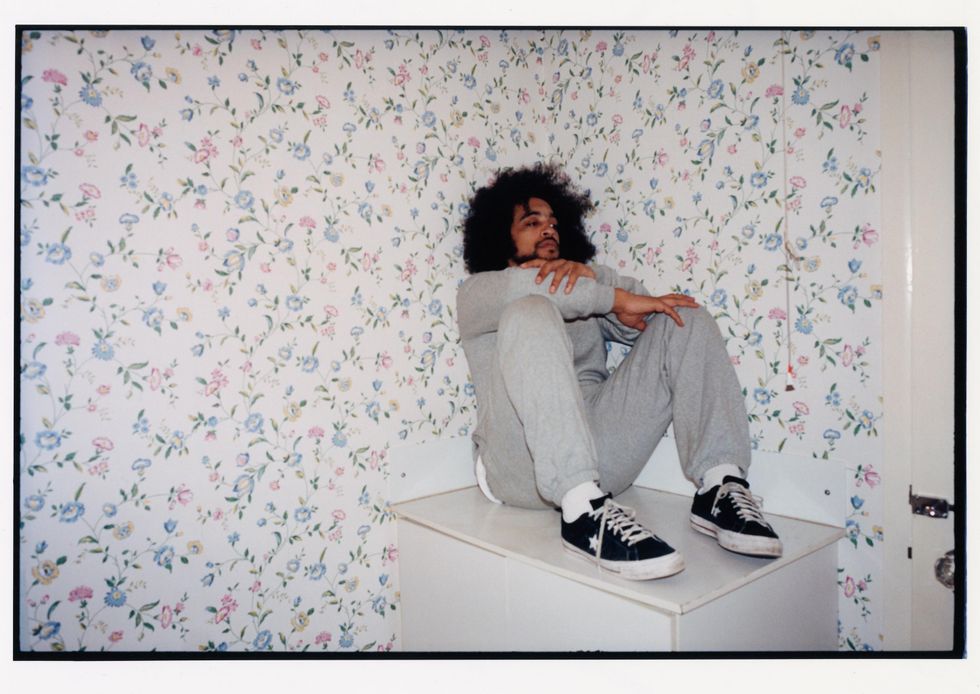

Photo by Machine Operated

“‘Broken Homes,’ the last song on LOGGERHEAD, is a real special one,” he says, reflecting on the song’s mood and origins. “We made that in lockdown, and it was just me, my boy Jae [Jaega Francis McKenna-Gordon] on the drums, and my boy Tag [Tagara Mhiza] on bass. We went to jam in this pub that was empty—because it was Covid lockdown—and it was half six in the morning and we were about to go to bed. But my friend Jae was like, ‘Let’s just play one more time—one more time—let’s have a vibe one more time.’ That was the beginnings of ‘Broken Homes.’ We recorded the whole thing to tape. It was a 20-minute thing that I edited down and reworked. My twin brother, Ben, helped me finish it—there were moments in it where I thought, ‘These are really good moments, but something’s not hitting’—and my brother, being a songwriter, suggested adding little ideas in how to change the arrangement to make it feel full. I was like, ‘Alright,’ and it was finished.”

That commitment to a song’s emotional, somewhat mystical, origins, coupled with a hyper-focused work ethic, is definitive of how Romans-Hopcraft operates. And, like most of his story, he also attributes that to his South London neighborhood.“

A lot of what I got from a lot of the people that I’ve met along the way is the thing I think they got out of college, which is learning how to practice,” he says about the many local graduates of the Trinity Laban Conservatoire he knows. “It’s learning how to be productive with your practicing, and that’s what I’ve applied to my own stuff, too. I’m like, ‘I’m not the greatest guitar player or bass player—I can hold my own for my own thing—but I’m going to learn how to make the MPC groove or take bits and create that into something.’ I took that and applied it to my own craft. And I had the support of all the other people around me as well.”

Wu-Lu - live from The Room

Wu-Lu and his band perform live versions of “Ten” and “Broken Homes” from LOGGERHEAD at the Room Studios in South London.

![Devon Eisenbarger [Katy Perry] Rig Rundown](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=61774583&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

Luis Munoz makes the catch.

Luis Munoz makes the catch.