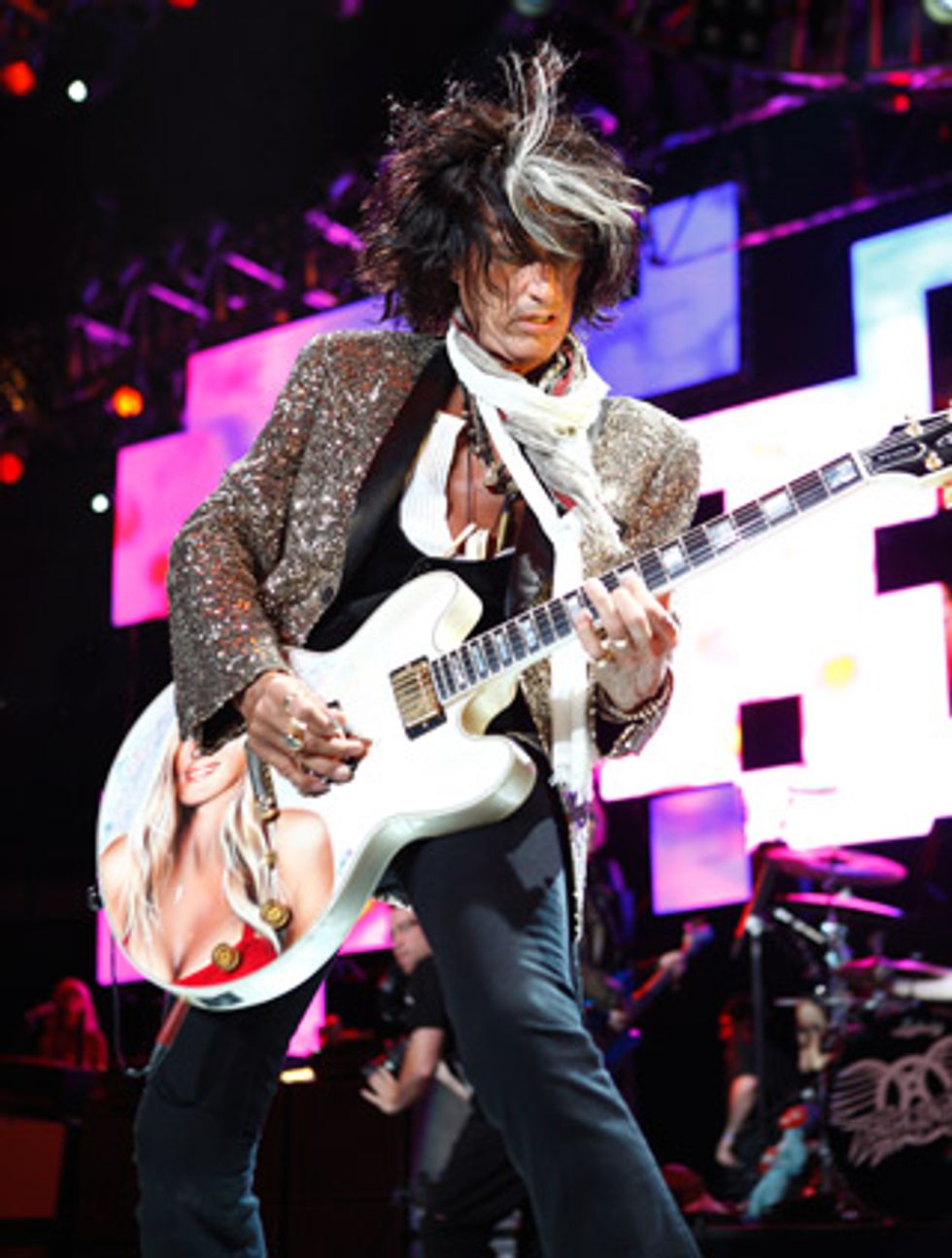

Photo by Ken Settle

What do you get when you combine nearly 40 years of grade-A American rock ’n’ roll, seemingly never-ending internal squabbles, and some of the most downright anthemic riffs ever? Why, Aerosmith, of course.

From the outside, the last decade or so has been pretty slow for the boys from Boston. Since the release of Just Push Play in 2001, not much original music has emerged from the Aerosmith camp. The tabloids were quick to blame everything from the typical lead singer/guitarist infighting to Steven Tyler’s (almost) solo career and even American Idol. But the band came together this year and is touring full force with a new album in tow. Music from Another Dimension is an album, for better or worse, that touches on everything Aerosmith is known for: big riffs, lush ballads, and plenty of production.

That production is fingerprinted by Jack Douglas—the man behind much of the group’s ’70s output. The old-school ethos that populated Aerosmith classics on Rocks and Toys in the Attic come back to life in the grit and attitude of “Out Go the Lights” and the bluesy snarl of “Street Jesus.”

Right at the center of this rock tour de force are two of the most revered and respected guitarists ever to strap on a Les Paul: Joe Perry and Brad Whitford. Much like Ronnie and Keef or Malcolm and Angus, the Perry/Whitford partnership is equal parts oil and water. On paper it might not line up exactly, but the proof is in the pudding. We recently caught up with the guitar duo the day after a sold-out show at Madison Square Garden to discuss the band’s somewhat tumultuous creative process, discovering new guitars, and what tones inspire them.

The struggles over the last few years within the band have been well-documented. How does it feel to finally get this album out the door?

Joe Perry: We tried to make this record probably—well, legitimately—three times. We set up some phone calls with Rick Rubin and talked with him about possibly doing the record. After that, we got together with Jack Douglas with the intention of coming up with a new studio record but the vibe wasn’t right and people weren’t in the right headspace. There was a tour coming up and we had time to work in the studio with Jack, we just didn’t have time to play everything from scratch so we decided to do a blues record, the Honkin’ on Bobo record. Then we got together with Brendan O’ Brien and spent some time with him and that ended quickly. In between all of this the band was still touring. It wasn’t like the band was sitting on vacation and trying to decide if we were going to make a record. As the years kept going it was really frustrating to not have anything new to play. It was time.

Brad Whitford: Yeah, long time coming. The last couple of years, it just seemed like we were ready. It was almost two years ago, we got together to do some writing and putting ideas together for the album and that was a very creative session. We felt like the light was finally green and we could start working on it. Especially after we had the initial session. The ideas were really flowing.

Even with all the personal setbacks, did you ever feel the band was at a creative lull?

Brad Whitford: We had a lot of personal issues—people going through stuff in their lives. Yeah, different issues going on for certain members of the band. We just weren’t very good at being a band for a while. We got past a lot of that stuff and started to get more interested in being serious about seeing if we could get something done.

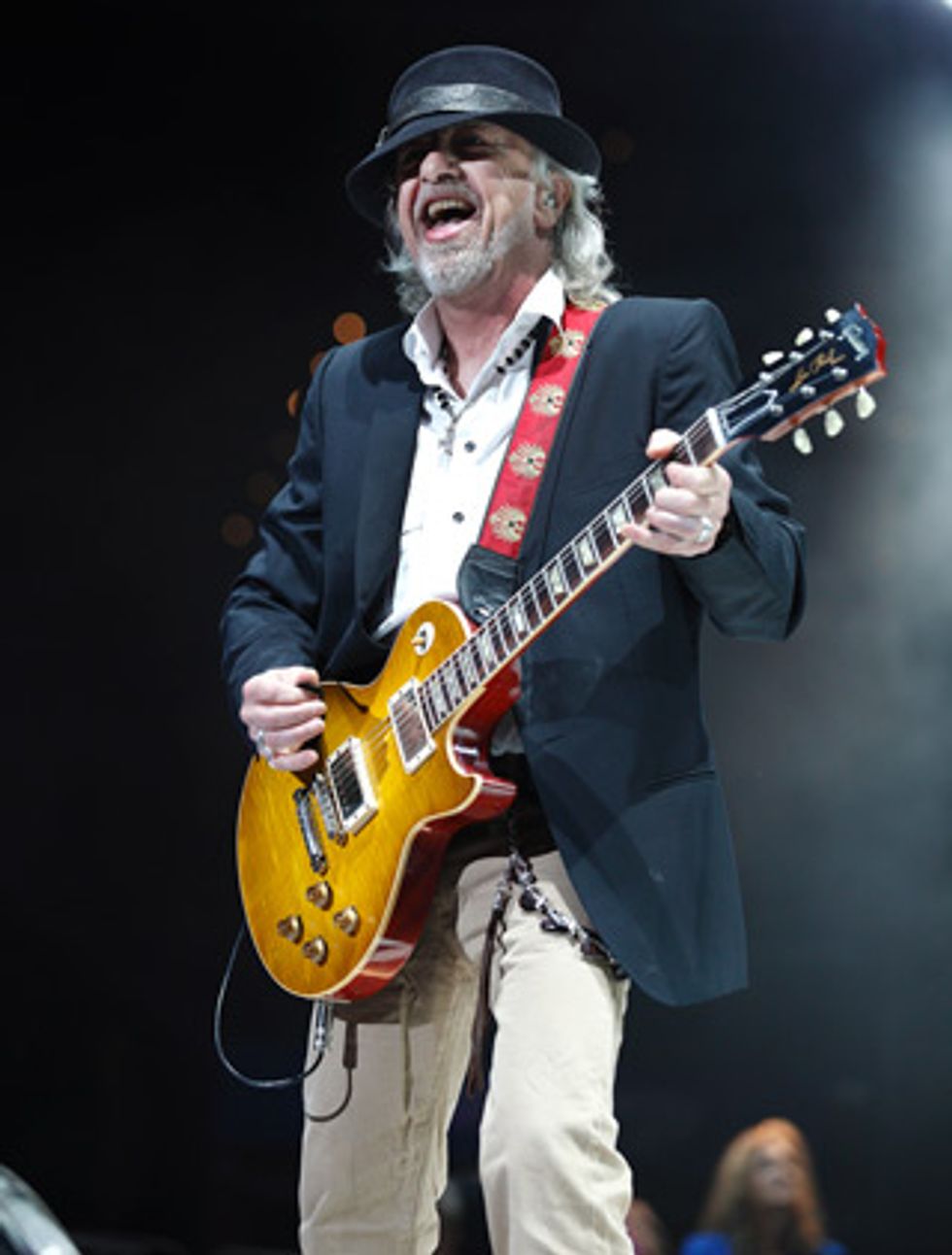

Photo by Ken Settle

Joe Perry: We had a lot of material from all those different sessions and even jamming onstage. We would jam and then tell the sound guy to mark the tape and some of those riffs ended up in songs. We certainly could have done another record two or three years after Just Push Play, but the time just wasn’t right. The good side of it was we had a lot of good material to pick from.

Is there an example on the album that you are particularly proud of?

Brad Whitford: That “Street Jesus” song. It’s funny, a majority of that song I have been kicking around for years and years and years. Sometimes, that’s how these things happen. These songs just fall out of the sky on your lap and other times they are years in the making. It was something I just kept bringing to the table for years and never really could find a home for it. I never really knew what it was going to be or what we were going to do with it. When we started on this album, I put it on the table again and it just took off and caught fire. That’s another thing—if you have a good idea and you believe in it you have to be a bit persistent. Find a way to make it work and make it into something that the other members of the band can really sink their teeth into. But everybody has to be into it.

Does the creative process differ between bringing in a riff or a sketch of a song and a fully formed demo?

Joe Perry: It’s all the same. The way Jack Douglas works is that he wants to be as transparent as he can be, as far as what the song sounds like. He wants to pull everything he can out of the band. For example, on this album there were a few ballads written with Steven and Marti Frederiksen and Marti produced them. People use different producers for different songs sometimes and Marti is the kind of producer that writes songs and then produces. Jack is the kind of producer that really lets the band be what it is and Aerosmith, coming out of the era we came out of, is all about playing live and cranking the energy up and entertaining the audience. That thread—that fire that runs in our veins that started it back in 1970— that’s still there and Jack recognizes that and knows that the best way to record the band and to get the most out of the band is to get us out there and playing. Whether I come walking in with a complete and finished song, warts and all, or if someone has two riffs that work together and the band hammers it out and turns it into something—just as long as they end up songs. And that’s how Jack works. On “Freedom Fighter,” I wrote everything in a day. It was like 5 in the morning and I wrote the lyrics and then I have this studio, so I wrote the music for it. It was basically a finished song when the band played on it.

Brad Whitford: Yes, I really do think that Jack has an understanding of what this band is trying to do and has always tried to do. He gets it in a very intimate way and understands it and how it works. When it’s working at the highest peak he is able to analyze it and understand it. He can put his finger on it and is able to bring the best out in everybody—it’s just the way he works and his personality. It’s almost like he is a member of the band. So, it was great to work with him and a lot of fun. He is such a fun-loving guy, he is very upbeat, so we laugh a lot. We keep it light, but very serious. We work hard.

When we caught up with Joe’s tech, Trace Foster, this summer he mentioned that different combinations of amps, pedals, and guitars inspire you from night to night on the road. Was there a specific combo that inspired you during the sessions for this album?

Joe Perry: I use a Klon [Centaur] pedal. That’s my go-to drive pedal and has been since we first got ours. I think the guy was in Boston and gave both Brad and I some of the early ones. There’s just something about them, they seem to give that extra push but without getting in the way of the sound of the amp or the guitar. It’s just a really good all around pedal. It’s also a matter of if you are in the studio or live. In the studio you have a lot more freedom to fool around with single-coil pickups because of the hum problem, the RF, and all of that. I have a Stratocaster that I use almost exclusively for my Strat-type stuff. It’s a ’57, but it doesn’t sound like any other Strat I‘ve ever heard, but it has a hum that you can’t deal with live. You might find a building once in a while where it works, but most of the time when you start getting it up to the volume you need it to be, it just hums like a bastard. I also have a couple of bastardized Jeff Beck Strats that work really well. The other thing I would do is go direct into either a Neve preamp or a Spectrasonics preamp. When you use them live, there’s so much hum and the way that they were built, it’s almost like the sound or tone disappears. But, when you plug them directly into the board you don’t have to deal with the amplifier thing and you actually get the sound of the fuzz tone or whatever it is. Very often I would split the signal and go into my amp, or combo, and the board.

Brad Whitford: I suppose there are probably several of those. Over the years I have managed to put together a few little amplifiers that really guarantee a great sound and that helps inspire you. I have this really ancient Marshall cabinet that is in decent shape but I would be afraid to take it on the road. First of all, I wouldn’t want to lose it. But it is one of the best-sounding guitar speaker enclosures I’ve ever heard. It has the original Greenbacks. It’s probably a mid-to-late-’60s-era cab. It’s one of those things that’s hard to explain but is unbelievable. I will always use it in the studio—or almost always, depending on where I am.

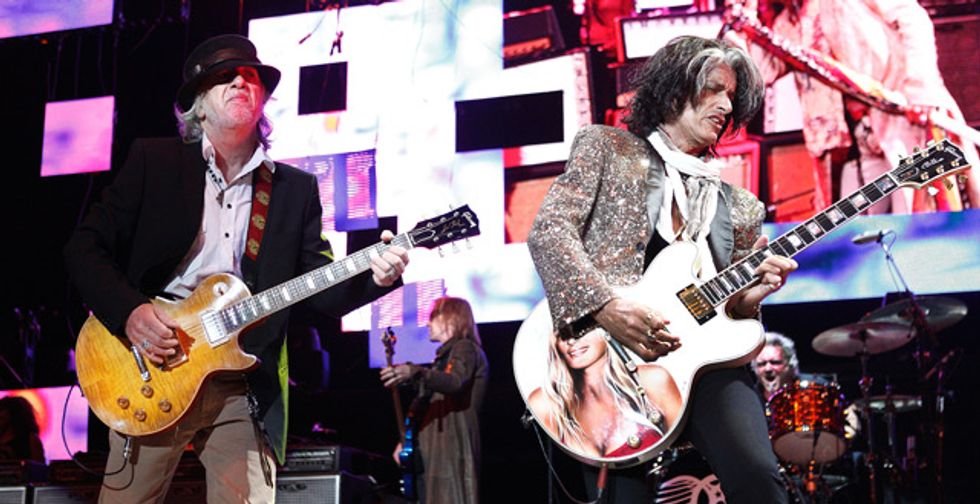

Photo by Ken Settle

Did you discover any new pedals or amps?

Brad Whitford: I can’t think of anything terribly new. I try and keep the pedals at a minimum in the studio. I just like the purity of the sound. I want the guitar and a cable into an amp and hopefully I don’t have to add anything to that. Unless it calls for it, like some flange or chorus. I try and keep it as pure as you can. A good guitar with a good amp, then the idea is to get a great performance. You can have all that shit and get a shit performance and you got nothing. I really like hearing something that is pure performance and isn’t enhanced in any way. I have one amp actually, that I found when we were doing these sessions. It’s a ’59 Fender Bandmaster. I believe that Pete Townshend used that same type of amp for a lot of the Who stuff. And now I know why! It’s just an amazing, amazing sounding amp, if you can find a good one. It’s a combo–a 3x10 combo. I can plug anything into it—Strat, Tele, Les Paul, it just works flawlessly.

This summer on tour you both were using Echopark guitars. How did you discover them?

Brad Whitford: His [Gabriel Currie] guitars are pretty amazing. My guitar tech, Marco Moir, was telling me about this guy and then when we got into the studio one of his guitars showed up. We plugged the thing in and thought, “My god, something really special is going on.” Since then we have become good friends and he has built a bunch of guitars for Joe now. They are just amazing. They have the soul of an old guitar because he makes them from ancient wood. The wood really makes a difference. He has a real talent, you know, it’s not always an old piece of wood that is going to work. You have to get the right one and have some sort of intuition or ability to actually listen to the wood and know that it’s going to sound good with some strings on top of it.

Joe Perry: Yeah, I think Brad has had one for a few years now. I saw it in his stack. I didn’t really pay much attention to it but Gabriel came down and brought a couple for me to try and I have to say they are probably some of the best-sounding boutique guitars that I have heard—hands down. I use one live pretty much every night. He is just really amazing and he has an ear for detail and is a real artist when it comes to building guitars. He gets it. It’s funny, we’ll be talking about building something idiosyncratic, he will text me pics of it as he is building it. It’s kind of fun to finally get the guitar and if there are little changes we can send it back and he can tweak it. He has also done some work on some of my other guitars, you know, setting them up a little better, especially the Strats.

What specifically does he do to set up your Strats?

Joe Perry: It’s the balancing the tremolo bar and adjusting the action. Because the whole thing, at least for my playing, is I like to have enough range in the bar and then making sure the height of strings is just right high up on the neck. I don’t know, he works some kind of magic in there. But his real forte is turning two pieces of wood into one piece of wood. Gluing the neck on instead of screwing on the neck; doing the dovetailing thing and putting the neck on the guitar and how much of the neck should go into the body—he’s analyzed all that.

When a song begins to take shape, how do you decide who takes the solo?

Brad Whitford: It just seems to be a natural, organic process. That’s another place where Jack might step in and say, “You should play this part and you should play this part.” A lot of times the song just dictates it. Jack might say, “I don’t know what it is, but that has to be a Brad Whitford solo or a Joe Perry solo.” I don’t know what it is but they just speak to us.

For example, Brad, how did the solo on “Tell Me” come together?

Brad Whitford: That’s a song that Tom [Hamilton] has had for some time. I don’t want to make it sound old, it’s not that old. But, we were working that up and it was becoming a unique thing all on its own. We were in the studio one day and Jack said, “I want you to go write a solo for this. Think George Harrison.” I went into this office with a copy of the song and my guitar and sat there for about two hours and came back out. That was it. We got it. I tried to think a little bit like George Harrison.

Are most of your leads worked out?

Brad Whitford: It’s different for different songs. Most of the stuff in the studio will be improvised. Other cases, like “Tell Me” I just wrote the whole thing.

Joe Perry’s Gear

Guitars

1957 Fender Stratocaster,

Dan Amstrong Ampeg (tuned to Open A),

Gibson "Bllie" Custom Lucille,

Gibson Joe Perry Signature one-pickup Les Paul prototype,

Gibson Joe Perry Signature Boneyard Les Paul,

Gibson Joe Perry Signature Les Paul,

BC Rich Bich 10,

Fender Jeff Beck Esquire replica,

Fender Telecaster with B-Bender,

Chandler Lap Steel,

Echopark Blue Rose,

Ernie Ball/Music Man 6-string bass,

Fender Custom Shop Strat,

Echopark Ghetto Bird,

Fender Custom Shop Tele (E5 tuning)

Amps

'69 Marshall Plexi (KT66 tubes),

'70 Marshall Plexi (EL84 tubes),

Marshall JTM45 Reissue,

Jet City JCA20H,

Friedman Dirty Shirley,

Budda Verbmaster,

'65 Marshall Bluesbreaker,

'70 Marshall Major

Effects and Accessories

Bradshaw Switching System,

Custom Siren pedal built by Rob Lohr,

Boss DD-7 Delay,

Dunlop Jimi Hendrix Cry Baby Wah,

DigiTech Whammy I,

Electro-Harmonix POG,

Ernie Ball VP Jr. ,

Klon Centaur,

TC Electronic Flashback Delay,

TC Electronic Hall of Fame Reverb,

TC Electronic Vortex Flanger,

MXR Carbon Copy Analog Delay,

Duesenberg Gold Boost,

Option 5 Destination Bump Boost,

Shure ULX-D wireless unit,

RJM Effects Gizmo,

Digidesign Eleven Rack

Brad Whitford’s Gear

Guitars

Fender Custom Shop '62 Strat reissue,

Fender Eric Johnson signature Strat,

Epiphone Inspired by John Lennon Casino,

'67 Fender XII 12-string,

Echopark Downtowner,

Gibson '58 VOS Les Paul

Amps

PRS HXDA,

Fender Twin Reverb Custom 15,

3 Monkeys Virgil,

PRS MDT 100,

3 Monkeys BW 119,

’59 Fender Bandmaster

Effects and Accessories

Fulltone Wah,

Pigtronix Philosopher's Rock,

Pigtronix Disnortion,

Boss TU-2 tuner,

Framptone Amp Selector,

Mojo Hand Rook,

Pigtronix Fat Boost,

Xotic EP Booster,

BK Butler Tube Driver,

Eventide Time Factor,

TC Electronic VPD1 Vintage Pre-Drive,

TC Electronic Flashback Delay,

TC Electronic Vortex Flanger,

TC Electronic Corona Chorus,

TC Electronic Hall of Fame Reverb,

Fulltone Supa-Trem,

Voodoo Lab Pedal Switcher

Click here to watch Rig Rundowns of both Brad and Joe's rigs!

For this album you combined both analog and digital technology for the main tracks. What was the advantage and how exactly did you do that?

Joe Perry: When we recorded the basics, we brought in the CLASP [Closed Loop Analog Signal Processor] system. Basically, it turns the 24-track, or whatever tape machine you use, into a piece of outboard gear so the first thing it’s hitting is the tape machine after it comes off the mic. From there, it goes into Pro Tools, so you are recording on the tape, but also recording on Pro Tools. It locks up with Pro Tools and helps add that warmth to the sound because the way Pro Tools is now, it just about reproduces everything you put into it. You have to take those extra steps to get that warmth and part of that is hitting the tape before it goes into Pro Tools. It is a little better than taking it straight off of Pro Tools and after that we then mix it down to a 2-track tape.

Brad, have you ever considered doing a solo album?

Brad Whitford: Oh man, well if I ever get myself together. I’m not sure how I would approach that because a couple of my sons are amazing players. I think we might do a family album since I have these amazingly talented guitar players in my family. One of my sons played with us last night at Madison Square Garden, so they aren’t slouches. I think that would be a good angle and be more musically interesting rather than just do my own solo album. That seems to be just musical masturbation.

Joe, now that this album is finished, do you have any plans to go back to the Joe Perry Project?

Joe Perry: Yeah, I am going to be working on that this winter as well as my autobiography. It will probably come out next October or November. I feel like it’s time and at the same time I’ll be working on some new music. Whether it takes the form of a whole album or if it’s something that coincides with the book, I haven’t figured that out yet. We’ll see how much time that takes over how much time I can get in the studio.

Is there more to the Aerosmith story?

Joe Perry: What about the last 20 years? Think about it. Walk this Way was written 12 or 15 years ago and it was mostly about the ’70s. The way I see it, there is a huge gap between the time the band got back together until now; stuff that has been in the papers, and how I ‘ve managed to survive through this. It’s an autobiography—it’s the Aerosmith story and my story through my eyes. It’s my truth about it and having a pretty good seat through the whole thing since 1970. I have a pretty good view of the way things developed. The other book that was written, it’s cute, okay? It has all the little stories about throwing TVs out of the windows and getting f**ked up and me leaving the band. I don’t think there is anything in there about my adventures with the Joe Perry Project for three years or talking about five solo records that I have done. There’s stuff that has been written about Aerosmith and not all of it true, but it’s my book, it’s not an Aerosmith book.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)