Lightning Bolt, a bass-and-drums duo from Providence, Rhode Island, is known for their unhinged live shows. They made their name performing in the pit, on the floor, and amidst the mayhem. They stand, along with their mountains of gear, in the middle of the crowd, surrounded by a “front row” locked arm-in-arm. Their shows are visceral and loud. They’re sweaty, and they can get gross, too. But there’s also a camaraderie and family feeling in the trenches—as if everyone is integral to the success of the performance. In recent years, the band has migrated onto the stage, but that all-for-one-and-one-for-all vibe still permeates their concerts.

Lightning Bolt is drummer/vocalist Brian Chippendale and bassist Brian Gibson. The duo started in the mid ’90s when they were students at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). They spent most of that decade gigging around town and defining their sound, but it wasn’t until their 2001 release, Ride the Skies, followed in 2003 by their epic, Wonderful Rainbow, that the band really started to take off.

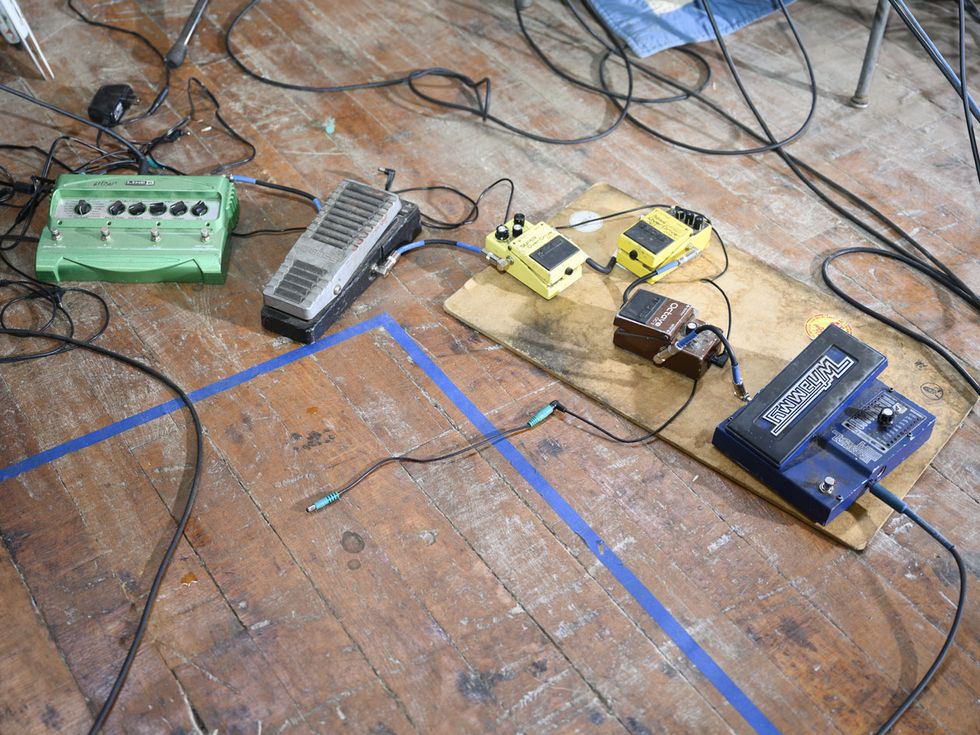

Gibson holds down the bass chair, but also handles the frequencies usually played by a guitarist or keys. He does that with a mutant 5-string bass: three bass strings plus two banjo strings tuned up an octave on the instrument’s high end. That, plus various overdrives, an unusual whammy-octave pedal pairing, an inordinate number of speakers, and thousands of watts of power, help him cover a large swath of sonic real estate.

Lightning Bolt’s most recent release, Sonic Citadel, follows in the footsteps of their 2015 offering, Fantasy Empire. The band, known as much for their untethered improvisation as their exacting arrangements, experimented on that previous outing with doubling parts, overdubbing, and other forms of studio trickery, expanding their sound well beyond their proven live-on-the-floor aesthetic.

Sonic Citadel expands on that methodology. Some songs, like “USA Is a Psycho” and “Air Conditioning,” are aggressive but structured, with definite sections. They’re built around Gibson’s gnarly bass parts that jump between registers and give the illusion there are more musicians at work. Part punk, part prog, the songs are edgy blasts of adrenaline and noise. But the album has a quieter side as well. “Don Henley in the Park” is a pastiche of subtle arpeggios and delays that were improvised in the studio and reorganized in post-production.

“All our records have some quieter pretty things,” Gibson says in reference to “Don Henley.” “But recording at Machines with Magnets [a studio in Pawtucket, Rhode Island], we had the ability to copy and paste sections and edit in a way that we couldn’t before. We knew the record needed a dynamic shift to something softer and more beautiful. We jammed for a little while. There might have been a section that went on too long that we cut shorter, and then an ending part that we stuck on. It also might not have been the exact sequence that we played. Plus, all of those parts were improvised.”

We caught up with Gibson on the phone from Providence to explore the band’s history, his unconventional approach to stringing and tuning his instrument, the trials and tribulations of setting up in the middle of a moshing crowd, and the long and painful saga of his ever-growing, ever-evolving rig.

When did you start playing bass?

My grandfather got me a bass guitar when I was a sophomore in high school. He asked me and my brother what we wanted to play. My parents had got me a trumpet when I was little and my mom also wanted me to play piano. I never really got that into them, and I think my grandfather understood that I would be into music if it was something a little more cool.

Tidbit: Lightning Bolt recorded Sonic Citadel at Machines with Magnets, a studio in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, where they also cut their previous album, Fantasy Empire. It was here the duo began exploring digital editing and layering techniques, in contrast to their earlier live-on-the-floor approach.

Did you take lessons or learn off records?

At the time, I was listening to the Who a lot and I was trying to play along. Back then, I didn’t think of John Entwistle as the greatest bass player or anything, but I really liked the Who. Only now I realize how revered he was. That band influenced me a lot, just because they have so much energy and it’s so wild. A lot of John Entwistle’s playing isn’t following rules. It’s noodling around, and I started off playing bass like it was a lead instrument, which I think came from that.

What was your gateway into more experimental or improvisatory music?

That was just going to RISD. That environment had a lot of creative people. Everyone was trying to outdo each other with how weird they were and how unique they could play their instruments. Everybody had their own identity. I was really into the ways that people there played instruments.

You were more influenced by local players than bigger names?

In my freshman year at RISD, Boredoms [an experimental noise-rock band from Osaka, Japan] came. They played in Providence and a bunch of people from RISD went to that show. I think everybody just completely had their minds blown. That show was a huge turning point for me. The big takeaway was that music can be anything you want it to be. It doesn’t have to fit into any category. I got really excited about the idea of starting a band that just does its own kind of music.

When did you start Lightning Bolt?

We started playing around ’94, and it was just done with pure noise. Brian was a pretty amazing drummer and he was playing these tribal beats—more straight. He was on the toms all the time. He was so loud and I just had this little 15" speaker, I couldn’t hear myself over him very well. I was just physically hitting the strings on my bass with my fist and trying to make the loudest rumble possible while he was creating this rumbling tribal rhythm. It sounded like thunder. That’s not exactly why we named ourselves Lightning Bolt, but it was pretty fun. We had a period in the beginning where we were playing with a singer, this guy, Hisham [Bharoocha], and we recorded a little bit of that stuff. I listened to it five years ago. Those recordings are kind of lost, but when I heard the recordings … I remembered it sounding like a rumble, but it actually sounded kind of grungy and ’90s in this weird way.

Because of the types of riffs you were playing?

There’s a little bit of a funkiness to the feel—how Brian is playing drums and the way I was playing bass. I was banging on the strings, but it was kind of like this slap bass, almost. Back then that made more sense to me. Now when I picture that, it sounds dated.

When did you add the banjo string?

The banjo string probably came around ’97, a few years after we started. The bass by itself, to me, sounds a little gray and dull. When Brian and I started playing as a two-piece, when we listened back to the recordings, it just needed that dynamic range. I wanted to hear really high notes, just to break up that sludginess. It is the role that a guitar has in a band, and because it was just bass and drums, that’s why I added the banjo string. I’d also seen Melt-Banana and I remember really liking how high that guitarist’s sound would go. He would play these super high notes with a slide. It might have been seeing them also that made me think, “I want to be able to do that. I want to be able to go up high.”

Do you also use a slide now to get those notes?

No. I use a Whammy pedal to get an extra octave higher. I used a battery for a while, just while we were practicing, and I got into doing some slide stuff, but it was almost more trouble than it was worth. In the context of a show, I don’t like the idea of having to put a slide on and start using a slide and take it off. Having gear for different parts of songs … that just seemed kind of annoying.

Did you add the 5th string for the same reason?

Yeah. Actually, the one string is almost enough, because it doesn’t sound great if I play chords with the two banjo strings, but it adds a little extra to have two. At some point, I needed to replace my bass and I thought that I’d get a 5-string and try two banjo strings. But it wasn’t a huge bonus. I think one high string is enough.

Why a banjo string and not a guitar string?

Just the length; they’re longer. Someone told me that maybe acoustic guitar strings are longer. I’ve wanted to figure out some way, because banjo strings are harder to find. It is a specific kind of banjo string that’s the right length. I think it’s for tenor banjo.

Do those thin strings cause problems with the neck?

It's not as much of a problem as you might think, but, as it is, my necks always seem to go out of whack after a year. But usually just messing around with the truss rod fixes it.

Gibson’s axe is a 5-string Music Man StingRay that’s rigged with banjo strings on its two high positions. The three bottom strings are tuned in fifths, like a cello, rather than standard fourths. “On the last record, we tuned the low note down to C, which is C-G-D for the low strings,” says Gibson. Photo by Nick Sayers

How do you tune it?

I use cello tuning, which is in fifths instead of fourths. On the last record, we tuned the low note down to C, which is C–G–D for the low strings. I like when the strings are loose, and we did this record with really loose tuning.

But normally you don’t tune that low?

That was a change for this record and it was an experiment. We didn’t write the songs tuned that low. When we got into the studio, we thought maybe this would be better lower, and I’d be able to play it better because the strings were looser. I really need the strings to be good and loose when I’m playing these songs. I don’t know why. But I want to bend strings a lot when I’m playing.

Are you going to tune it low when you go on the road?

I think so. When we go on tour, sometimes I don’t bother even thinking about tuning. I am not playing with anyone else. Maybe at the beginning of the tour I am tuned to C, but by the end of the tour I am tuned to A. No one would know the difference.

It’s not a problem with the vocals?

Yeah, Brian will get annoyed if I am way off. He does get used to the notes he sings as a vocalist. But often I am tuning the strings more for the action and the playability. It’s all relative to me. Maybe someone could tell me that it’s really meaningful, the difference between an A or a B or somewhere in between, but I am almost randomly tuning every day. I think, “The action is low, I should tighten the strings a little bit.” But I do keep it in tune with itself.

In the early days, you had a lot of problems with amps blowing up. How did you solve those problems?

The whole history of Lightning Bolt is me buying bigger and bigger rigs until they stopped blowing all the time. In the beginning, I was using a Hartke 350-watt combo amp with a 15" speaker, which was all I could afford, but it was still pretty expensive. That thing would blow up, like, every two months. I’d have to take it to this guy in town, he’d fix it, and that would cost $200. But I couldn’t afford a new amp, so I just kept getting it fixed. At one point, I bought an 18" speaker, which made everything twice as loud. That was eye-opening for me—that I could be that much louder by adding speakers.

For practical reasons, Gibson prefers simple Boss, DigiTech, and Line 6 pedals for his core effects. “Stuff is constantly breaking,” he says. “It’s really nice to go on eBay at any time and have a new pedal the next day, or go to a music store anywhere and be able to get the exact same pedal and have the exact same sound that you had. Photo by Scott Alario

But the combo amp kept blowing. I then got the Hartke 350-watt head/tube preamp with a SWR 4x10 and an 18. I kept adding more and more speakers, but the amp kept blowing up, although it was sounding better and better. I did this until around the year 2000, and I was totally broke. That was when I quit. There was a period when I quit Lightning Bolt, because it was too much. I wasn’t getting enough out of it. We weren’t that popular at the time. I was working at a coffee shop and I was just broke. I moved to New York City for a year. When I was in New York, I got a job making a mural and I was making a lot of money. But as I was there, I was getting frustrated because there was no good music happening in New York. There weren’t any good bands. It seemed like people were just going out to bars and drinking and working all the time.

Bass

5-string Ernie Ball Music Man StingRay

Amps

Ashly BP41 preamp

Two QSC PLX 3602 3,600-watt power amps

Two QSC K12 12" speakers

Two 18" speakers

Two SWR 4x10 cabs

Effects

Boss SD-1 Super Overdrive

Boss OBD-3 Bass Overdrive

DigiTech Whammy

Boss OC-2 Octave

Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler

Boss PW-3 Wah

Strings

Various gauge and brand bass sets (strings 5-3), and tenor banjo strings (2 and 1)

That’s New York.

I felt like I wasn’t going to go anywhere in my life if I stayed there. I saved up $10,000, which was a lot of money for me at the time, and I thought, “I am going to go back to Providence, buy a huge bass rig, and try and do Lightning Bolt again.” I got a fancy 1,200-watt SWR bass amp, I forget what it was called … and two 4x10 SWRs, and two 18" subwoofers. It was a lot bigger. It is still not what I have now, but it was great. I got that nice rig and I could suddenly hear the notes I was playing. That’s when we recorded Ride the Skies. That was our first record where the bass sounded clear. When we released that record people started to notice us, and when we played shows a lot more people started showing up. I was playing with that rig for the next few years. Actually, that SWR amp was still blowing up every few months.

What was the problem?

The power amp was getting overheated and it would cut out. It would short out in the middle of shows. I was turning everything all the way up—that was the problem with the Hartke, too. To play with Brian, I needed to be at this volume that was just pushing everything too hard. A few years after I came back to Providence from New York and I was playing that much bigger rig, but it was still blowing up, I started buying fancy power amps. Now I am using these QSC 3,600-watt power amps. I discovered that it is less of a problem on your speakers to be super-overpowered, but not going into the red, then to be underpowered, but turning everything all the way up.

Why is that?

Clipping is what blows speakers and overheats amps. I still turn up and go a little bit into the red with everything, but I am pushing so many watts now. Plus, now I am using these powered speakers that are really powerful and never blow. Actually, I’ve blown those speakers sometimes, too.

Do you use monitors, too, or are your speakers enough?

I started using monitors more. We used to play on the floor all the time, so that wasn’t an option. When we started playing on stages more, I didn’t really understand the power of the monitors onstage for a while. Now I am very interested in getting things to sound good onstage using the monitors. In the beginning, I just assumed that my rig had to sound good and that’s all that mattered.

When you play on the floor, do you still run everything through the PA and boost it through the house system?

It’s always different. It depends on the space. I like trying to still go through a PA system if we play on the floor, but it’s usually not possible. It’s a lot of cables everywhere and usually the sound people don’t want to take that risk of having a bunch of mics and cables where all the chaos is. It is pretty chaotic when you play on the floor.

Do you have problems with people stepping on gear and knocking stuff over?

We used to have a lot of problems. When we played on the floor a lot, we would routinely have people trample my pedals and kick the cables out of my pedals in the middle of the set. People would knock Brian’s drums over. That was part of it. It was really frustrating and whenever that stuff would happen I would get pretty upset, but I think, at the same time, people liked that chaos.

Gibson and Chippendale formed Lightning Bolt in 1994, after they met at the Rhode Island School of Design. In a sense, their practice of playing live in the center of the room or bringing the audience onstage is as much performance art as music. The Talking Heads also have their roots in RISD. Photo by Scott Alario

The sound guys probably weren’t thrilled when you showed up. Or did you have all your own stuff? Did they get the night off?

That’s a lot of why I blew speakers and why my equipment has been such an issue for me, because we didn’t use PAs for a long time. Maybe if we were starting from scratch now and we decided that we were always going to play on a stage, I might play with a little Fender practice amp and just use the monitors. But it is always going to be an issue playing with Brian. He’s just an extraordinarily loud drummer. So even the stage monitors aren’t enough by themselves.

You use Boss pedals for overdrive and distortion.

I like the Boss stuff because it is easy to replace. Anywhere you are, they have it, and I am just not a big tone person. I am interested in tone, but I am not interested in the perfect tone. A lot of people get these really fancy boutique pedals, but I don’t know what you do if you’re on tour and it breaks or you lose it. I wouldn’t want my sound to depend on something that’s fragile, or something that if I go to Europe and it doesn’t work … which happens all the time to me, stuff is constantly breaking. It’s really nice to go on eBay at any time and have a new pedal the next day, or go to a music store anywhere and be able to get the exact same pedal and have the exact same sound that you had.

You also use a Whammy and octave pedal together at times.

Yeah. A lot of the earlier records use this combination of whammy-ing up an octave and then using the octave pedal to go back down an octave. It creates this thick, tight sound that you just can’t get any other way. “Dracula Mountain” on Wonderful Rainbow, or “Assassins”—a lot of our classic Lightning Bolt-sounding songs use that Whammy up and then octave down. If I just play the bass with the octave on, everything is too muddy and low, and if I play everything with the Whammy up, everything is too high and weak sounding. But having both of them together sounds amazing, powerful, and clear. So that’s a big thing. The octave by itself can be really heavy. If there’s times where we want a really heavy part, I’ll use the octave by itself. But then you can set the Whammy to play chords. More and more lately—and on this new record—I use that setting on the Whammy pedal. It makes a fourth, and it sounds like you’re playing a power chord.

In the early days you did a lot of improvisation. Is that still a big part of what you do?

We both are just naturally improvisational. When we get together, we don’t want to play songs usually ever. But for some reason our shows—I think because we like to structure our shows in a way that’s fun for an audience—end up being a series of songs. Then there are moments in between when we might go off doing some improvisational stuff.

How composed are your songs?

They’re pretty worked out. We’re weird creatively. We have a hard time with a middle ground. If we’re going to structure something, we probably structure it too much. We’ve often talked about how it would be cool to write a song that’s in between being structured and improvisational, but it just seems like, with us, that something is either 100-percent structured or 100-percent improvisational. It’s hard to have any rules if you’re improvising.

The music that’s structured—will you play the songs the same way every night on tour?

Sort of, yeah. There will usually become sections of songs where we start to tweak or we’ll open something up. We usually have a few parts of our set where we allow ourselves to do an improvisational portion, but we even structure that. There are often times where Brian gets really wound up at the end of a song and he just starts going insane. I’ll try and accompany what he’s doing. Or we’ll have a break in between two songs and I’ll start noodling around some high, pretty melody. Then Brian finds a vocal line that goes with it and it turns into a segue. Stuff happens. Because there’s two of us, we do have some agency to take a sudden left turn during our sets.

You’ve been playing together long enough that you can probably read his mind a bit.

We’re both probably predictable to each other.

Do you overdub in the studio?

There’s some overdubbing. We play everything live and then I will replay the bass lines to make it stereo—so we can put one version in the left speaker and one version in the right speaker. There is a little bit of a studio trick happening.

Is that a new thing for you?

We did that on the last record, too. It was something I had qualms about. But in regard to the last record, people said, “This sounds so much like how it sounds when you play live.” I realized that when you make a record, you are trying to create the illusion of the live experience. We’ve always wanted to be super-authentic about the performance in the past. A lot of our earlier records are “the take.” There are no overdubs and there’s nothing changed about it. But the last two records, there’s been a little bit of an effort to try and make it so it really conveys the energy that the songs are meant to convey and that it has the attitude that the live show has. Even if it means doing the stereo effect on the bass, but that’s basically it. We will do retakes of the vocals.

Do you use your live rig in the studio or pare it down?

I pare it down. I go through my pedals, amp, and directly into the board from there. Fantasy Empire was no amp—just the pedals into the board. This one, it sounds different from Fantasy Empire, because I am going through the amp now. It’s a pretty crazy sounding solid-state amp. I think this record sounds a little more aggressive because of that. It sounds more like what I sound like live.

YouTube It

Aboard the Brusov Ship, a multi-use arts and culture space in Moscow, Lightning Bolt strikes a blow for freedom of expression with this thunderous and chaotic version of “Colossus,” from their 2009 album, Earthly Delights.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)