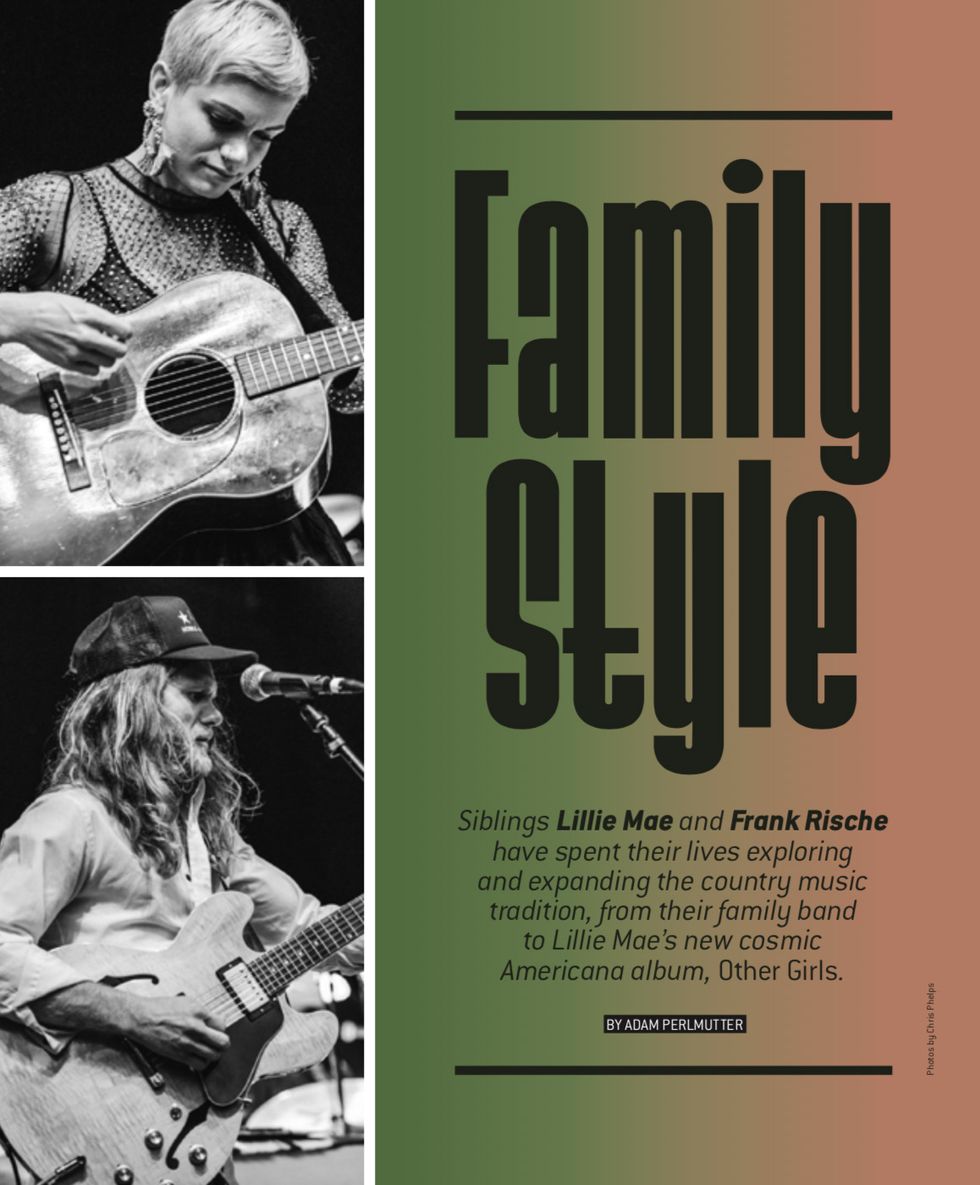

Last year, for the first time in what felt like an eternity, the Nashville singer-songwriter, fiddler, and guitarist Lillie Mae decided that she needed to slow down. So she took a break from her heavy touring schedule to encamp in RCA Studio A, one of a pair of recording studios behind the Nashville sound established by Chet Atkins and country and pop legends. Lillie Mae emerged with an excellent, left-of-center country album, Other Girls. It’s her third studio effort, and one that finds her stretching out in creative directions and playing plenty of fine steel-string guitar throughout.

It was unusual for Lillie Mae, whose surname is Rische, to have gone to this introspective place, as she had been playing out pretty much since she was a toddler. Lillie Mae and her five siblings all learned music very early on, under the tutelage of their father, Forrest Carter Rische. Beginning in the early 1990s, the family had an itinerant lifestyle as it traveled the southern United States in a motor home, performing its brand of rootsy music at any available venue, from theme parks to pig pickin’s. (For non-Southerners, the latter’s a get-together that involves barbecuing a whole hog.)

In 2000, the Rische family received a break of sorts when it was asked to audition for the singer-songwriter and producer Cowboy Jack Clement in Nashville. Clement sensed great potential in the family, and, in particular, Lillie Mae, who at the time was just nine. He acted as a mentor to the young musician until his passing, in 2013. Meanwhile, Lillie Mae, her brother, Frank, and her sisters, Scarlett, Amber-Dawn, and McKenna Grace, formed the band the Risches (later changed to Jypsi, pronounced gypsy) and became a fixture on the musical stretch of Lower Broadway, in Nashville.

While Jypsi achieved some level of success after it signed to Arista Nashville, in 2007, Lillie Mae began writing songs on her own. In 2012, she met Jack White, and White, feeling instant musical chemistry, asked her to join his band the Peacocks as a fiddler and mandolin player. But when White realized her originality as a songwriter, he supported her in pursuing that direction. White first produced Lillie Mae’s 2014 debut single, “Nobody’s” backed with “Same Eyes,” and then her 2017 full-length album, Forever and Then Some.

Though Lillie Mae is clearly steeped in the country tradition, the new album, Other Girls, is at once old-school and modern. In spots, it feels like textural music placed in an Americana context, with some of the instruments, particularly the electric guitars, receiving a bit of an ambient or even psychedelic treatment—unusual for a country record, and also a bit of a departure for the album’s producer, Dave Cobb.

While gearing up to tour in support of Other Girls, Lillie Mae called from Nashville, where she lives, as did her brother, who also plays guitar on the album. Both reflected on how their early life on the road shaped the musicians they would become. And though she considers herself a fiddler first and foremost, Lillie Mae explained why she would almost always rather play the guitar.

The new album, Other Girls, is packed with beautiful guitar sounds. What instruments are you playing?

Lillie Mae: I’ve had a few different guitars recently that I’ve gotten rid of, because they weren’t right for me. Right now I’m playing a Gibson LG with an L.R. Baggs [Anthem] pickup. I’m also playing an old Harmony—that was my first guitar, which my brother fixed up for me. And he was kind enough to loan me the nice Bourgeois [Vintage D] that I’ve also been playing.

What makes you get rid of a guitar—and what draws you to one?

Lillie Mae: The ones I’ve gotten rid of have been really nice guitars, but I really got them just because I got good deals on them. They were newer and they just didn’t speak to me. I wasn’t inspired to write on them or anything. I really have found that I just kind of lean towards older guitars. When I pick out my next guitar, I’m going to get just the right one. I really love early-’70s Guilds. I’ve never had one, but I’ve really enjoyed playing them. There were two down the street from me here at Carter Vintage, and I was drooling over them for a minute.

What kind of guitars did you use on the record, Frank?

Frank Rische: Well, I tell you what. I brought in a number of guitars. Also [producer], Dave Cobb has a pretty nice selection of guitars and amplifiers. Honestly, he’s probably got just about everything that you would want at the studio. I used Dave’s ’60s 12-string Rickenbacker, his killer ’60s Gibson ES-335 and also my own 335. And I played my Tele-style guitar and Gretsch Double Anniversary. We went through various amplifiers. I have an old Gretsch [6163 Executive] with a 15" speaker. I think it was made by Valco in the ’60s. I used that as well as my 1960s Fender Princeton, and assorted other amps that Dave had in the studio.

TIDBIT: Producer Dave Cobb set up Lillie Mae and her band in a circle and did the core of the recording live in his current roost, Nashville’s historic RCA Studio A.

I can hear a sparing amount of tasteful effects on the album. What did you use for the crunchy tones on tracks like “Whole Blue Heart” and “Terlingua Girl”?

Frank: That’s just a germanium fuzz pedal. I also used an MXR Phase 90 in spots on “Terlingua Girl” and other places on the album, and I know that Dave came back and [overdubbed] a few things—like the crazy electric parts at the end of the track.

What was growing up in a family band like?

Lillie Mae: Our family was on the road full-time. We lived in a motor home and we played anywhere we could. We played RV parks, recreation halls, fairs. We did a lot of gospel and we played a lot of churches, flea markets, and stuff in Texas. So, yes, my family has been in music my whole life, and I’m just a product of that. We’ve been living in Nashville for almost 20 years now, and I’ve never taken a break—just always gigging and recording at every opportunity. We still play together, record a lot, and have a lot of fun here.

Frank: Well, I’ll tell you, man, it was definitely an extremely different life and, playing at a young age, we were kind of just thrown into it. It was our family’s means of making a living and our everything. But I certainly loved playing from the very get-go, and I can’t remember a time that I wasn’t always around music.

We moved to Branson, Missouri, in the early ’90s, when I was about 6 and Lillie was 1. We would play a lot of theme parks and malls around in the area, and in the winters we would go down to South Texas and play for the winter Texans in their RV parks and churches. There would always be lots of people jamming and you’d just learn from them. So it was a little different.

We were kind of all over the place. We lived in Asheville, in the mountains of North Carolina, for a time, playing a lot of pig pickin’s and opries and fire halls. We never had a whole lot of scratch, and we ended up moving to Nashville and living with some people out in the country on their farm. Then we met a guy named Dave Ferguson [an engineer known for his work with Johnny Cash]—Fergie they, call him—who introduced us to Cowboy Jack Clement, and that’s how we ended up where we are.

In a pre-show huddle at Los Angeles’ Greek Theatre in July 2019, opening for the Raconteurs, that’s Lillie Mae’s sister Scarlett, at Lillie Mae’s right, and her brother, Frank, at left. Both play a key role on the new Other Girls and were part of Jypsi. On drums is Misa Arriaga. Photo by Chris Phelps

What’s it like to make music with your family?

Lillie Mae: I’m just blessed to play with my brother. He’s done all my solo stuff and all but three or four shows in as many years or something. He is one of the best guitar players alive. He could seriously have any gig in the world. I mean, he is un-fucking believable. He’s a musical genius and has put freaking 50,000 times more work into his instrument than I have.

Frank does a lot of session work—mostly modern country music—but he doesn’t really advertise it. People would never know it, because he’s such a nice and humble person, and he just leisurely does his thing. But he’s on loads and loads of material that’s being played on the radio and stuff like that, and I know that he won’t always be available for my work, being as he’s so busy, so I never take playing with him for granted.

Frank: First of all, I love playing with all of my siblings. They’re all extremely talented, and we have something special going on. Just the fact that we’ve played together and sang together for so long, being family and all, we definitely share a kind of natural musicality. And I think I’m the biggest Lillie Mae fan. She’s always one of the best musicians on acoustic guitar or on fiddle, piano—whatever she’s doing. When we play together, whether on instruments or vocal harmonies, a lot of times I can anticipate where she’s going, and we just meld. I’m happy we still get to make music together after all these years.

Lillie Mae, do you think of yourself as a fiddler first, or a guitarist?

Lillie Mae: I currently play more guitar than fiddle—I play acoustic on all my solo music—but I feel like, overall, fiddle’s definitely my main instrument and it always has been. I’m actually a better fiddle player than guitarist. But the truth is, I never want to get off the guitar [laughs]. I always loved guitar and actually played it before I played the fiddle.

What speaks to you more about the guitar then the fiddle?

Lillie Mae: Man, I don’t know. I sing and stuff, so maybe it’s just that you can’t really accompany yourself that well with the fiddle. If I sing a song, I’m just going to play guitar. I’ll never forget starting to learn the guitar when I was 4, picking up “All I Have to Do Is Dream” by the Everly Brothers and “Sloop John B” by the Beach Boys. I remember sitting on a picnic table and just trying to figure out the guitar—which I still haven’t quite done!

Frank, though you’re of course a great acoustic picker—as is obvious from YouTube videos—you play mostly electric on the album. Which instrument feels more like home to you?

Frank: I guess I feel pretty natural playing electric, even though I really haven’t played it professionally for all that many years, and just on a few random recordings. It’s definitely a different instrument, with a different feel and learning curve. But if I had to pick one for eternity, I would probably play acoustic, since it’s what I’m most accustomed to.

Though there’s so much great guitar on the record, every note seems to be of service to the song. Talk about your writing process.

Lillie Mae: Songwriting for me is always the same drill. I just write when it comes to me, when it comes through me. So I wasn’t writing for anything specific. In this case, I had been writing for a while, about the things I’ve known, and just had a bunch of material ready to go. On the other hand, I’m always happy when someone asks me to write for something specific. It’s great to have something to write about and give it a whirl.

How often does it happen that somebody asks you to write something specific?

Lillie Mae: Well, almost never. But one time my mom asked me to write something for a woman that she used to take care of. And I wrote some gospel thing, but I never played it for her. She’s still around, though, and I really ought to do that [laughs].

When there was a Luck Reunion session that Third Man Records released, I did a collaboration with Langhorne Slim, and we had to write two songs. I had never met him, but I came to him with one idea and then the second song was his idea. It was wonderful and super fun to collaborate and flesh everything out together.

And when I first started dating my boyfriend, he was, like, “Hey, write me a song.” He was just joking, but we actually did write something for each other. His song was awesome and mine, not so much. But it was just so much fun, and it was a cool reminder of how I can hash out a new song without having to wait till it comes.

Guitars

Gibson LG with L.R. Baggs Anthem electronics

Harmony acoustic

Strings and Picks

Assorted D’Addario strings and picks

Guitars

Bourgeois Vintage D

Gibson ES-335

Gretsch Double Anniversary

Amps

1960s Gretsch 6163 Executive

1960s Fender Princeton

Effects

MXR Germanium Fuzz Face

MXR Phase 90

Strings and Picks

Assorted D’Addario strings and BlueChip picks

What was the recording process like for Other Girls, which has a cool, live vibe?

Lillie Mae: Thank you very much. It’s with my longtime cast and crew, plus a different drummer [Chris Powell] and, this time, producer Dave Cobb, which was amazing. So that was different for me to have branched out a little bit. We tracked everything live, so everyone was just kind of sitting in a circle. It was a really cool recording experience. We worked pretty quickly, and it was really great to get in there and record again with a bunch of new tunes. A lot of my songs have natural arrangements, and these came together as we were working in the studio.

Did you give the other players specific ideas of what you wanted them to play?

Lillie Mae: I had a very different vision of how it was going to turn out. We’re all pickers, and we tend to solo on everything [laughs]. So for me to make an album where there’s no solos was kind of different, but it just happened naturally, you know? I mean, the people on the album, like the other guitar player, Greg Smith, are unreal musicians. I thought he would go crazy on the B-Bender Telecaster or something, but that just didn’t happen.

But to answer your question, it wasn’t like, you play this; you play that. Things like the mandolin parts that my sister [Scarlet] played just seemed to have been built in when the songs were written.

Why do you think it is that the songs on this particular album didn’t call for soloing?

Lillie Mae: Man, I don’t know. In my mind it seemed like certain songs would call for something like a steel-guitar solo. But in the studio, things seemed different. The songs are just kinda personal, and I guess in the end it was more important for them to be supported by interesting parts in the background than full-on solos. It wasn’t what I anticipated, but it worked. It is what it is.

Frank, how did you arrive at your guitar parts on the album?

Frank: Lillie obviously wrote the songs and just let them take the shape that they wanted to. Most of the stuff we just worked out in the studio, creating little variations on the melody together until everything jelled. But generally, it was more like a feel thing than something really planned in advance.

Would you say that the kind of unexpected outro to “A Golden Year,” where the instruments join together and speed up, is one of those details that emerged in the studio?

Frank: Yeah, we just had the instruments doing this repetitive line, which speeds up and kind of gets crazy. It was so much fun to play.

It sounds like there’s lots of improvisation in the details on “A Golden Year” and the other songs.

Frank: I improv all the time, but I’m not going to go crazy away from the melody. I just try to play something that suits the song, while getting just a bit away from the original lines. If you play anything for a while, I think that will just kind of happen naturally.

On a different note, how have you both found your own voices within the country tradition?

Frank: I’ve spent a lot of time practicing to records of different people. Tony Rice was a huge thing for me growing up and still is. For a long period of time, I played to a lot of Alison Krauss & Union Station records and tried to understand what they were doing. I’ve always listened to a lot of different styles of music beyond classic country as well. I’m always trying to broaden my horizons musically and stylistically. But I’ve never felt like I wanted to play exactly like somebody … definitely always wanted to have something unique and just play something tasteful that means something for the song. I think it’s cool when people learn the exact licks or notes of something amazing, but I think it’s also pretty important to put your own spin on things.

Lillie Mae: Shit, I don’t know. I feel like it’s hard when it’s yourself—you don’t really notice. I don’t feel like I found my voice. I feel like I’ve always had this. I’ve always been the same.

Lillie Mae, with Frank Rische at her left, plays a short set including “Didn’t I” and “You’ve Got Other Girls for That,” both from the new Other Girls album, for the Ringer website’s live music pages. Lillie Mae sticks to her comfortable Gibson LG and a fiddle, while Frank plays a Fender Jaguar and his ES-335.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)