Lukas Nelson is having a busy year. He and his band, Promise of the Real, recently released their third full-length album, Something Real, and hit the road in support of it. They’re also touring and recording with Neil Young as his backing band—a project they began last year with a lineup augmented to include Lukas’ brother, Micah. In addition, Lukas somehow finds time to accompany his dad, country legend Willie Nelson.

But despite his pedigree and the auspicious company he keeps, Nelson is no next-generation-of-greatness clone. While he counts his father as an obvious and huge influence, that didn’t stop him from absorbing the classic riffs and tones of artists like Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, and Jimi Hendrix, the blues feel of Stevie Ray Vaughan, Hubert Sumlin, and the three Kings, and the improvisatory exploration of the jam-band world. His work ethic is serious, and he’s developed significant chops, killer tone, and stylistic flexibility. It didn’t hurt that he shared a stage with Buddy Guy, Young, and other titans along the way.

Something Real was recorded at the William Westerfeld House—a San Francisco landmark that was once home to Janis Joplin, jazz saxophonist John Handy, and a group of Czarist Russians following the Bolshevik Revolution. Its many rooms, nooks, and crannies provided an amazing and varied sonic environment, while its history and location provided the vibe.

We spoke with Nelson as he was traveling through the Rockies en route to Texas. Here he discusses his influences, techniques, recording approach, side projects, songwriting, and why he isn’t much of a gearhead.

It’s probably safe to assume you heard a lot of music around the house growing up. When did you start playing the guitar?

When I was 10 or 11 years old. Dad and mom never really forced it on me. They just had ’em lying around the house. It was something I could do to get closer to my dad actually, because he was gone all the time. I thought, “If I start playing guitar, maybe that’s something we can talk about.”

Listening to your music, it’s obvious you had other influences—like Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath.

Oh yeah, I love Sabbath. I love Zeppelin. I went to San Francisco one time and my mom got me Stevie Ray Vaughan and Jimi Hendrix [albums]. I started listening to them and had a kind of religious experience and fell in love with them. And then I had my dad as an influence, too. So it was like a marriage of those two musical styles that I really love—rock ’n’ roll and real country music.

it is just you.”

How did you develop your technique—did you take lessons or learn solos off records?

I listened to lots of records and I’d spend 8 to 10 hours a day playing. I took a few lessons here and there. My dad taught me the country chords. I even learned some Gypsy jazz playing from my friend Tom Conway in Maui. My friend Donnie Smith taught me about the jam-band world—the Grateful Dead and just going off and being able to improvise. I was pretty well rounded and I had some great teachers, but I just did a lot of [wood]shedding on my own.

Can you read music and do you know some theory, too?

I know a bit of theory. I can read a little bit, but if you stuck a sheet of music in front of me it would take me a long time to figure it out. That’s not how I learned, I learned by ear.

What’s that joke—how do you get a guitar player to turn down? Put a piece of music in front of him.

[Laughs.] That’s it!

Promise of the Real poses outside the William Westerfeld House, the San Francisco mansion where they recorded Something Real. Band members are, from lower left (clockwise): Tato Melgar (percussion), Micah Nelson (guitar), Corey McCormick (bass), Lukas Nelson (center—vocals/guitar), and Anthony LoGerfo (front right—drums). Photo by Jim Eckenrode

Do you use a pick, fingers, or both?

I use both: I fingerpick and I play with a pick. These days I’m using my fingers a lot more, actually. On my dad’s show, when I play with him, I only use my fingers now. Our tech, Tunin’ Tom [Hawkins], will tune the guitar and then I’ll just go straight into a Baldwin amp. I don’t have any pedals, nothing. It’s the same amp my dad uses. It breaks up great—those Baldwin amps are incredible.

It’s an older vintage amp?

Yeah. My dad uses one, and Neil has one, too—he has a big one. It’s the amp that my dad’s been using forever.

What amp do you prefer for your gigs?

For my gigs I have a Magnatone [Twilighter] amp, the reissue that Ted Kornblum has been doing, and they’re just incredible—they’ve got the greatest tone. Sometimes, if I can’t get those, I’ll use a [Fender] Super Reverb or a Deluxe Reverb together—I run two amps in stereo. But Magnatone is what I'm using right now.

How did you get your tones on the new album?

We put the amps in the library [at the William Westerfeld House] and walled them off. We had close mics and room mics. We created a little studio and it was the greatest thing ever. It was the coolest vibe out there, recording right in the middle of San Francisco.

Did you use your live rig or did you experiment with other gear?

I pretty much used my live rig, although it was during the recording of that record when I first started using Magnatones. We recorded it a year and a half ago.

What do you like about the Magnatones?

Just how they sound. It’s good tone, and it sounded real. It didn’t sound like a lot of reissues, where it’s maybe more high end. It’s real warm. They’re good-sounding amps and the vibrato is really cool.

Neil Young is obviously a fantastic and very unique guitarist. What’s it like playing with him?

Oh, I think he’s one of the best that ever lived. It’s an honor to play with him.

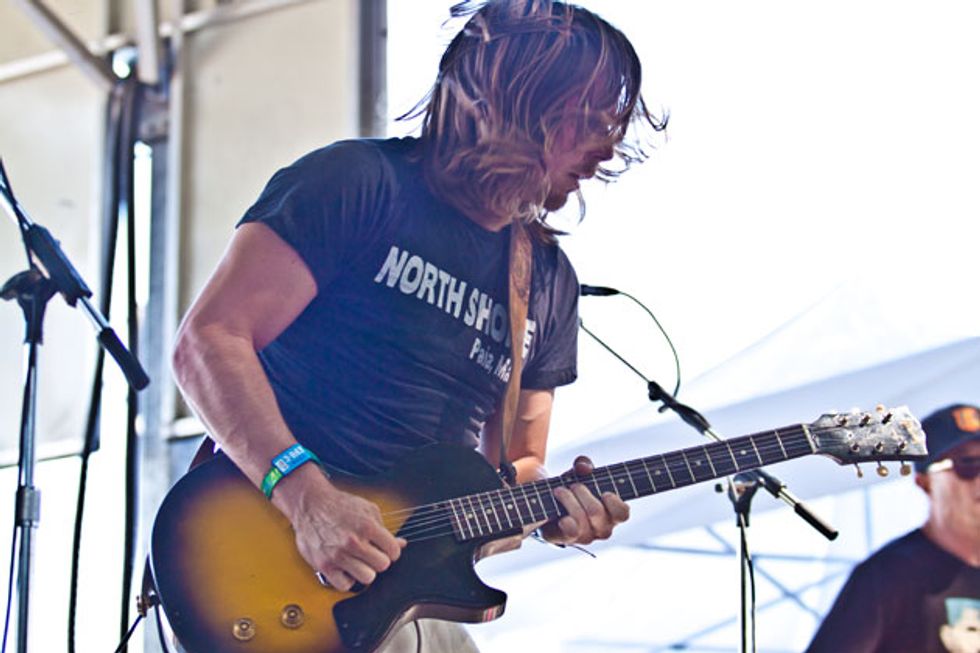

Lukas Nelson with his 1956 Les Paul Junior at Lollapalooza in 2013. Photo by Chris Kies

Musically, does he give you direction—tell you what to do—or just lead by example?

Just by example. He lets us be who we are and play how we play. He likes all our different styles—my brother’s style, my style, and his style. We go together well and it really translates well at the show. We did a lot of rehearsing before we played with Neil—we learned all of his songs. We’ve played over 200 shows a year for the last eight or nine years, so we’re pretty tight. We don’t really rehearse that much when it comes to our stuff.

Has being around him taught you any cool new lessons about playing or performing?

There are definitely little subtleties that just get absorbed when you’re around him.

Like what?

Well, I couldn’t even explain it—and I probably wouldn’t even if I could [laughs]. His attention to detail is really great. He’s got the wall of sound, he’s got his amps—and everybody knows what he does. He knows his gear, and I’d rather not sit and talk about his tone too much. I mean, I know he has. It’s special to him.

You play in your father’s band as well. What are some lessons you’ve learned from him?

I learned everything from him. How to be a performer, how to be in front of a crowd, how to connect with a crowd. Mickey Raphael is his harmonica player and has been for forever. He’s taught me a lot about being in a band—like when not to play. And then Aunt Bobbie [Nelson] has been playing with him for 40-something years. I mean, that’s one of the greatest band’s you’ll ever see. It’s simple and just pure talent.

I have to say, for me, it’s less about the gear and more about the person playing. That’s why I’ve never paid attention to gear, because my dad was more of a minimalist. He’s got the same guitar he’s been using for the last 45 years or longer [the famously worn Martin N-20 nylon-string that the elder Nelson calls Trigger], and he goes directly into an amp. He doesn’t use any pedals or anything, and that’s kind of what I’ve learned to be. It’s more about what you put into the instrument—what you put into your performance—that really connects with an audience. I think most of the tone is in your fingers, rather than in the gear itself.

You mean how you put your personality into the instrument?

I do. I’m not a gearhead. I believe it’s good to have a base of good equipment. If you went up there with a Squier or some kind of little guitar—a $200 guitar—then yeah, there would be a difference. But your tone comes from your fingers, how much time you put into it, and how much dedication you have to learning the subtleties of your instrument.

Lukas Nelson’s Gear

Guitars1956 Les Paul Junior

Late-’90s Fender Strat with Rio Grande bridge humbucker

Fender Strat

Amps

Magnatone Twilighter

Vintage Baldwin combo

Effects

MXR Preamp

JHS SuperBolt Overdrive

Strings and Picks

DR Strings (.011–.050)

Medium Guthrie Thomas picks

Do you find that you generally sound the same regardless of the gear you’re using?

Yeah, I do find that. It really doesn’t matter what pedal or whatever I’m playing. It’s like how Billy Gibbons could play a tiny little Vox amp and still sound like Billy Gibbons. I think there is a lot to gear, but personally I believe most of it is just you.

There’s definitely a heavy blues influence on the new record. Did you spend a lot of time shedding the blues when you were young?

Oh yeah, the blues are my first love. Like I said, I got into Stevie Ray Vaughan and Jimi Hendrix. I got into Albert King, Freddie King, B.B. King, T-Bone Walker, and Hubert Sumlin—all the old blues guys. I really love them.

Did you ever get to meet any of them?

I’ve played with Buddy Guy before on a couple of occasions. I love Buddy Guy. I’ve backed him a

few times—he’s great. There is a video of me, him, Dad, Lyle Lovett, Kenny Wayne Shepherd, Doyle Bramhall II, and Double Trouble—or Chris Layton at least—and Mickey Raphael. We’re all doing “Texas Flood,” a tribute to Stevie Ray and a tribute to Dad at Austin City Limits.

You use a nice combination of open chords and barre chords.

I’m not one of those guys who wants to make the song complicated just for the sake of it being complicated. I prefer simplicity over complexity. Sometimes if you just change one little chord to a minor or to a diminished, it just brings the song and the melody up to a whole other emotional level. I prefer simplicity, but I like to throw in a few things that are different here or there. I really like a good melody.

Do you experiment with alternate tunings?

I do some stuff with alternate tunings, but I don’t think I did with this record at all. I think it was all pretty standard, but tuned down half a step.

YouTube It

Lukas Nelson & Promise of the Real perform “Find Yourself” live from Jam in the Van at Willie Nelson’s Ranch during the SXSW Heartbreaker Banquet in 2014

Do you do that for your vocals or for the tone on your guitar?

I started doing it a long time ago when I was using heavy, heavy strings. I was using .012s and .013s for a while, and then I went back down to .011s. I guess I just got used to singing in that key. But sometimes I go back to normal. I think the next batch of stuff we’re doing is back in regular tuning.

What made you decide to use .013 string sets—Stevie Ray?

Yeah, I was listening to Stevie Ray and I wanted to get as close to him as I could for a long time—like a lot of guitar players do.

I think it worked them out good. Made them stronger.

The mid-’60s Baldwin C1 combo is similar to the S1 believed to be favored by Willie Nelson for decades now. Lukas Nelson uses the same model when performing with his father.

The Baldwin Connection

Lukas Nelson’s main amp since the Something Real sessions about a year and a half ago is a stock Magnatone Twilighter (a design by Obeid Khan and consultant Larry Cragg—Neil Young's longtime guitar tech—that was introduced under the newly revived brand back in 2013). But when Lukas plays in his father Willie Nelson’s band, he prefers to use the same amp as his dad, a Baldwin.Never heard of it?

In the mid 1960s, Baldwin, the piano and organ manufacturer, jumped into the guitar market. The company purchased Burns London, Jim Burns’ struggling London-based guitar outfit, and began building amps as well (by decade’s end Baldwin would also own Gretsch). In the late ’60s, Baldwin introduced the Model 801 CP Contemporary Classic—an electric nylon-string with a ceramic Prismatone pickup that ran underneath the strings on the guitar’s bridge—and this guitar was advertised alongside an accompanying amp. Willie Nelson owned and used both, though after the guitar was reportedly stepped on by a drunken fan decades ago, Willie had its Prismatone pickup installed in the iconic Martin N-20, nicknamed Trigger, that he’s been using ever since. He never stopped using the amp.

Willie’s Baldwin combo is most likely the Model S1, the Slave, a solid-state affair that maxes out at 100 watts and has both a 12" and 15" speaker. As he told Frets magazine in December 1984, “[I use] a Baldwin amp with a Martin classical guitar—which is kind of a bastard situation. I’ve tried other combinations, and I don’t get the same sound that I do with this one, which was really accidental … I’ve never changed it. I’ve tried to keep everything exactly the same … Each time I come across a used Baldwin amp, I try to buy it so I can use the parts for replacements on this one. I’ve got a couple of them.”

Most Baldwin models, in addition to standard EQ, volume, reverb, and tremolo controls, featured a groovy color-coded Supersound circuit. As Zachary Fjestad described the circuit in the July 2009 PG, “These were basically preset EQ settings for treble, mid I, mid II, bass, and mix. A three-way toggle switch allowed the user to switch between normal operation, Supersound operation, and dual operation. All of these effects could be switched while in operation, and according to Baldwin’s factory catalog, ‘Hear it, and you might think it’s a happening.’ Whatever that means!”

Willie and Lukas Nelson aren’t the only Baldwin users. Neil Young has one as well, although his model is the Exterminator—a 250-watt solid-state monster with two 15", two 12", and two 7" speakers. Yikes!

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)