Radiohead is one of those bands that’s so big it’s impossible to not know of them, yet somewhat easy to not really have much of an opinion about their music—or at least not a well-informed one. Unless you’ve purposely sought out the U.K. quintet’s tunes based on the mountains of accolades they’ve received over the last 25 years, there’s a decent chance your familiarity is limited to “Creep,” the alternatingly melancholic and manic single off their 1993 debut, Pablo Honey, that earned them lazy comparisons to Nirvana—and put them on the charts on both sides of the Atlantic.

But this strange dichotomy exists largely because the quintet—which has been together since 1985, when they were all students at Abingdon School, just outside of Oxford, England—has long been rather willfully obtuse and insular. Even before getting signed and jettisoning their original moniker, On a Friday, Thom Yorke (vocals, rhythm guitar, programming), Ed O’Brien (guitars, vocals), Jonny Greenwood (lead guitar, keys, programming), Colin Greenwood (bass), and Phil Selway (drums) were so staunchly Oxfordian that they refused to relocate and become part of the more high-profile scene in London—a mere 60 miles away. And, mind you, this stubbornness was way before they’d truly come into their own, too. This was when, as on Pablo Honey, their regard for bands like R.E.M., the Smiths, Pixies, Sonic Youth, and U2 was rather obviously worn on their collective sleeve. (Which is not to say that glimpses of future brilliance weren’t visible then, particularly in tracks such as “Blow Out,” which paired Yorke’s distinctive falsetto with Jonny Greenwood’s and O’Brien’s dynamic shifts between off-kilter jazz chording and crescendoing noise-rock implosions.) But the band’s obtuseness only grew from there.

When The Bends came out in 1995, it both proffered more singles—including “My Iron Lung,” “High and Dry,” and “Street Spirit (Fade Out)”—and demonstrated a more singular sound, with much more of the auricular adventurousness that would come to define the band. But it was the third outing that was the proverbial charm for the Oxfordshire five.

Released on June 16, 1997, Radiohead’s OK Computer struck listeners like a bleak yet startlingly beautiful soundtrack to a supercut collision between George Orwell’s 1984, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, and David Lynch’s Eraserhead. Chock-full of dystopian lyrics, it was augmented by both deliberately alien elements (such as the nightmarish sound collage and disembodied Macintosh-computer oration on “Fitter Happier”) and an expanded array of traditional instruments (including strings, glockenspiel, piano, and vintage keyboards).

by the guitar.

Just as importantly, its striking guitar work established O’Brien and Jonny as bona fide guitar icons for the coming millennium. And between its swelling, seething riffs, stuttering ping-pong’d echoes, and pedal-glitching feedback freakouts (“Airbag”), tinkling acoustics floating over gauzy layers of undulating, mutating textures (“Paranoid Android,” “Karma Police”), and chiming Rickenbackers (“Let Down,” “No Surprises”) were so many gorgeously addictive melodies that, for legions of fans, the record became the aural equivalent of the soma narcotic Huxley had written about. Over the years since, it’s gone on to be heralded by music publications the world over as one of the most important rock albums of all time, and, in 2015, it was entered into the U.S. Library of Congress as “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant.”

No Surprises … Except

Of course, anytime a band gets that sort of success and acclaim, there are vitriolic detractors. Naysayers then and now tend to dismiss Radiohead as overhyped, self-indulgent self-loathers. And, again, much of that opinion is probably a drawback of the band’s go-it-alone attitude, as well as the fact that they don’t really play the typical rock-star PR game. Offstage, the band members appear rather spotlight shy and protective of their privacy, doing very few interviews—and, sadly for us 6-string-playing fans, practically no guitar-oriented interviews. Yorke and Jonny are typically the most visible, with the former mostly talking to large general-interest publications about politics, and the latter pretty much only talking to very niche-y outlets about almost anything but guitar. Recently, however, this dynamic has begun to change a bit. At least partially.

In his hard-to-track-down interviews, Jonny—who has favored the same two or three Lace Sensor-equipped Fender Telecaster Pluses for most of the band’s career—still tends to express his distaste for guitar magazines and “the totemic worship” of the instrument. As he told The Quietus in 2014, “I’m always happiest … struggling with instruments I can’t really play.” (Although, to be fair, he did add, “I’d be lost if I couldn’t play [guitar] too.”) Even so, when Jonny does grant interviews, he’s typically more interested in discussing unusual instruments (such as the ondes martenot, an early-1900s keyboard) and—as a film scorer himself (including for Paul Thomas Anderson’s award-winning There Will Be Blood)—composers such as György Ligeti, Olivier Messiaen, and Krzysztof Penderecki.

Radiohead circa 1993 (clockwise from upper right): Ed O’Brien, Colin Greenwood, Thom Yorke, Phil Selway, and Jonny Greenwood. Photo by Neil Zlozower/Atlas Icons

On the other hand, O’Brien—long the Radiohead member who’s experimented with more guitars and seemed the least ill-at-ease in the spotlight—has stepped out from the shadows more and more over the last two or three years, and not just with mainstream publications. He’s appeared in videos by Fender and The GigRig, and, best of all, at long last we’re proud—ecstatic, really—to say he recently took the time to talk to Premier Guitar.

How to Disappear Completely

So what is it exactly that’s occasioned Mr. O’Brien’s recent magnanimity with guitar nerds? Only he could say for sure. But it seems that, in a way, it goes all the way back to the sessions that resulted in both 2000’s Kid A and 2001’s Amnesiac. Whether it was just part of the band’s already-in-progress evolution or in obdurate reaction to the adoration of OK Computer, both LPs went so far down the rabbit hole of electronica, string arrangements, and general experimentation (including the Charlie Mingus-influenced “Pyramid Song,” and the New Orleans-jazz dirge jam on “Life in a Glass House”) as to pretty much obliterate any hopes of radio play. In the process, the records also alienated a significant portion of fans who’d previously thought themselves hardcore.

In fact, from that point onward, the remaining faithful knew that if there was one thing they could count on, it’s that whenever a new Radiohead album hits, all bets are off for what direction it’ll take. And, at least according to O’Brien, it seems the same can be said for members of the band, too. “It’s constant evolution,” he says of the quintet’s writing process. “The essence of it is five people with a songwriter—Thom—who puts these songs within the context of the rest of us.” He adds, “By the time it gets to the rest of us, there’s only a certain amount of room left. At times you go, like, ‘What the fuck am I going to do?’”

This was why, for O’Brien, the band’s trek down unknown roads during the Kid A/Amnesiac period was particularly frustrating. Not because he didn’t want to go along, but because he was unsure of how to fit into the new sonic landscape forming around Yorke’s seeming urge to abandon all paths previously trodden. “I literally learned to play my instrument within the band, so I started off very limited—and I’m still very limited,” O’Brien confides. “Ultimately, the band’s not a welfare state. If you don’t come up with something that serves the song, then you’re not going to play on it.”

Understandably, the decreasing emphasis on 6- and 12-strings was daunting for O’Brien, who considers himself a guitarist first and foremost. Asked about how he adjusted, he contrasts his approach with Greenwood. “Jonny is an amazing musician, and he plays a lot of instruments. So he might seek a sound by going through an ondes martenot or a keyboard or a Rhodes or a piano.” In contrast, O’Brien says, “I seek out a guitar—or a different-sounding guitar.”

O’Brien confides of his go-to Rickenbacker 360 12-string, “I have to be honest—I really struggle with the 12. The neck is so narrow, and it’s a dog to play. But they have a certain sound.” Photo by Lindsey Best

For the Kid A/Amnesiac sessions, O’Brien’s lifeline “different-sounding” guitar ended up being the same Fender Eric Clapton Stratocaster he’d been playing for years—only now modified with a Fernandes Sustainer unit. For a player who’d grown up idolizing the Jam’s Paul Weller, Andy Summers of the Police, and the Smiths’ Johnny Marr—texturalists who specialized in creating space—it helped things fall into place. Paired with generous amounts of reverb, echo, compression, and pitch-shifting, the Sustainer-equipped guitar opened new possibilities and enabled O’Brien to help generate the lush soundscapes populating Radiohead’s early-millennium outings.

And yet, even after Hail to the Thief (2003) and In Rainbows (2007) hewed strongly back toward traditional guitar-rock form—with feral 6-strings blasting out of the gate on the former (“2=2+5”), and the latter being the band’s loosest, most traditional and soulful effort to date—everyone in their right mind knew it wouldn’t last. True to form, Yorke’s writing on The King of Limbs (2011) veered toward electronic trance vibes, and last year’s A Moon Shaped Pool was somewhere in the middle—a bit more of an organic band effort, with plenty of fertile fields for atmospheric Sustainer work amidst the fuzzy bass lines and string arrangements, respectively, by Colin and Jonny Greenwood (“Burn the Witch”), Yorke’s still-amazing falsetto and lilting pianos (“The Numbers,” “True Love Awaits”), fingerpicked acoustics (“Present Tense” and “Desert Island Disk”), and shuffling slow-builds haunted by otherworldly background vocals (“Identikit”).

Which brings us back to the question of magnanimity. About midway between Limbs and Pool, O’Brien began talks with Fender Musical Instruments Corporation about developing a signature guitar. Unveiled at the 2017 Summer NAMM Show in Nashville and available for sale in November, the EOB Sustainer Stratocaster canonized O’Brien’s long relationship with the classic double-cut by combining custom specs and his favorite mod in a single instrument. Meanwhile, he’s begun work on a solo album (to be released in 2019) with bassist Nathan East (Eric Clapton, Daft Punk), drummer Omar Hakim (Miles Davis, David Bowie), and singer/guitarist Dave Okumu from the band the Invisible, and he and his Oxfordshire mates were recently nominated for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

To be sure, O’Brien has a lot to talk about these days. And, given the dearth of past guitar-focused interviews, we’re sad to say we had too little time to cover the breadth of questions that have built up over the last three decades. But we did our best. Thankfully, Radiohead’s chief texturalist was the consummate gentleman, manifesting himself to be both an out-and-out guitar nut and a super-friendly guy. Two facts we hope bode well for getting the honor again sometime soon—perhaps even with Jonny in tow. (We can dream, right?)

Congratulations on the release of the EOB Strat. How did all of that fall into place?

Well, there was no kind of ambition to necessarily make a guitar or do a collaboration. It really came from a dream that I had. It was a very strong dream, and I can’t remember the details, but I woke up and immediately thought of the Sustainer Strat that I’d been playing—what we called the “Frankenstrat.” Plank [Peter Clements], who looks after the Radiohead gear, put it together, and I’d been playing it for about 12 or 13 years. I woke up—I was about half-awake—and I immediately fired off an e-mail to the one person I knew at Fender, a guy called Neil Whitcher [FMIC’s head of artist relations in Europe], saying, “Would you be interested in collaborating and making this Strat? I think we can make some improvements on it.” Within a few hours, Neil wrote me back, saying, “This sounds great. Let me pass it on to Justin Norvell [senior vice president of products at Fender].” I wrote to Justin, and that kind of set it all in motion really. In 2013, just over four and a half years ago, I wrote the e-mail. And here we are now.

What sorts of things did you hope to improve?

The problem with the one I had was that it was great when it was sustaining, but it didn't sound good as a normal, functioning guitar. What I wanted was to have this amazing Strat and—with a flick of a switch—you can enter a whole other world with the Sustainer. I wanted it to sound great in normal guitar mode. Another big thing was I wanted a really great neck on it.I love the [EOB] neck.

Did you ask for it to match something you already had?

No. I didn’t have a Strat that I was really happy with the neck. The Clapton Strat neck was good, but it wasn’t great for me. Fender flew me over to Corona and I went through the different profiles of necks. The one that we ended up with was a ’56.

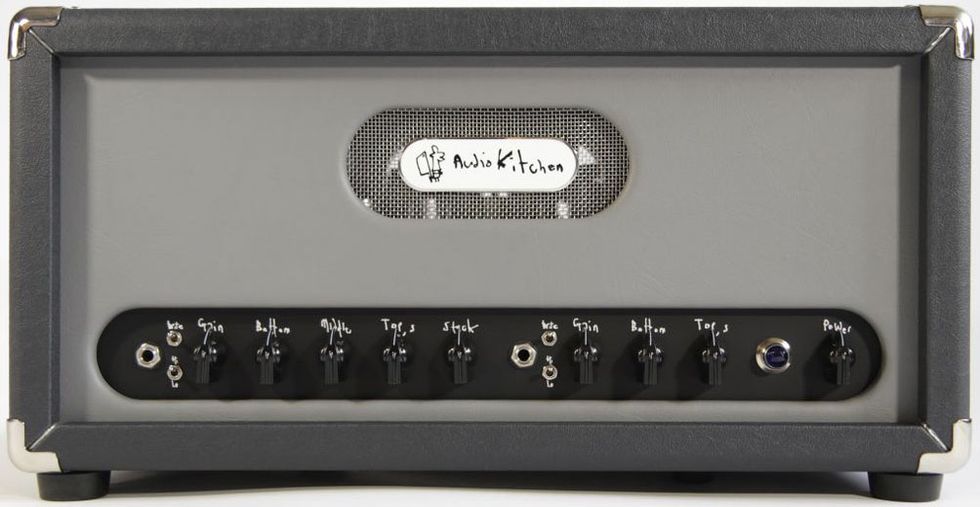

O’Brien had been using Fender Vibro-King Custom combos since the King of Limbs tour in 2011. However, due to volume concerns, of late he has switched to amps by Audio Kitchen, including the Big Chopper—a two-channel, class-A design driven by a quartet of EL84s.

You mentioned Plank a minute ago—did you ever toy with the idea of adapting a Starcaster as a signature model based on the semi-hollow guitars he built you years ago?

No, I felt like it needed to have the solid body for the sustain to be really great. But actually that’s a good point. I've never done it [put a Sustainer] in a semi-acoustic hollowbody. That would be really interesting.

Does having the signature guitar change how many guitars you take on the road?

It does. It’s made life a lot more boring for my tech, Adam. I think he used to really enjoy the fact that it was pretty much a different guitar every song. It kept him on his toes. Now we’ll go through the setlist, and 50 or 60 percent of it is the Sustainer Strat.

So how many guitars are you taking on the road right now?

Well, I’ve got three EOB Strats. I’ve got my [Gibson ES-]335, a Rickenbacker [360] 6[-string], a Rick [360] 12[-string], and I’ve got a lovely Gretsch [G6137TCB Panther]. That’s about it. It’s kind of minimal. I like being a little bit more nimble. I wouldn’t say we’re exactly nimble, but I like being light of imprint.

Are any of the EOBs in different tunings, or are they just backups?

Yeah, basically they are all backups.

Over the years you’ve experimented with different guitars more than Jonny does. Would you say that’s because you simply enjoy switching it up more, or did it have to do more with what you feel the nature of your role in the band is—as more of a texturalist?

I love guitars, and I’m very lucky to be in a band that encourages finding new sounds. My experimentation comes probably from my limitations, in the sense that I don’t play lots of other instruments, whereas Jonny does. I could have sought out other instruments, but I guess I’m fascinated by the guitar—that it has lots of different applications and sounds. I quite like having limitations, because certainly for me, it works to bring the best out.

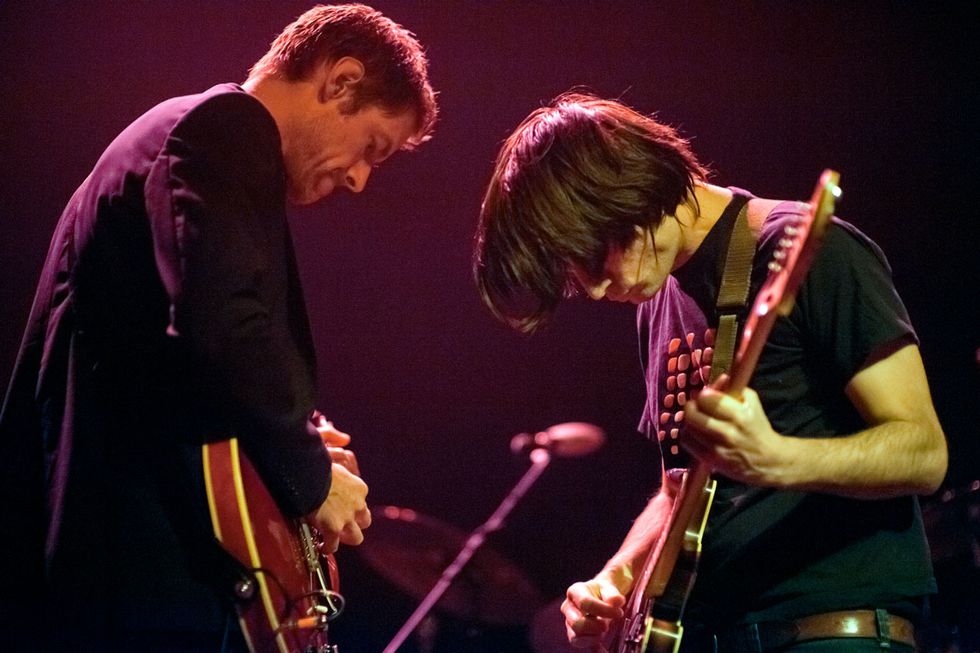

O’Brien (with his Gibson ES-335) and Jonny Greenwood (with his mid-’70s Fender Starcaster) onstage at a 2010 benefit concert for Haiti at the Fonda Theatre in Los Angeles. Photo by Lindsey Best

Rickenbackers have been a mainstay for a long time, too. What drew you to them?

I like the look of them! I mean, seriously—that was a big part. Also, they are iconic guitars, particularly in sort of the British lineage of bands, starting with the Beatles. For me, it was Paul Weller and the Jam, playing his Rickenbacker. That was a really iconic image. And Johnny Marr played a Rickenbacker in the earlier days. Then, of course, Peter Buck—that was his thing. I was a huge R.E.M. fan. Rickenbackers are expensive guitars, so when we got the record deal and I got the advance from EMI, I had a Squier Strat that I bought as a kid. We were all allowed to buy one guitar. Jonny bought his Tele Plus. Thom bought a Tele, and I was always going to buy a Rickenbacker. I used it a lot on Pablo Honey, The Bends, and I was still using it on OK Computer. “No Surprises” is the Rickenbacker with a capo. It’s a very distinctive sound—I still love it. I’ve been in the studio [recording] my own stuff, and I’ve still got a Rick 6 and a Rick 12 there.

Was your first one a 6- or a 12-string?

It was a 6. I have to be honest—I really struggle with the 12. The neck is so narrow, and it's a dog to play. I would love it if, someday, Rickenbacker did a 12-string that was actually really nice to play. I’ve got two 12s, and they’re just horrible. But they have a certain sound. It'd be really nice if they were nice to play and had that sound.

When you look back at your career—from the On a Friday days up to now—what strikes you most about your evolution as a musician?

I guess that I kept going, really. I literally learned to play my instrument within the band, so I started off very limited—and I’m still very limited. But I’ve been lucky, because I’ve been in a band that has not required you to be a virtuoso. It’s about doing something different. I think I’ve always enjoyed … I love sound. I think that’s the thing overall: I love sound. To me, as much as Brian Eno has been a huge influence, I’ve been fortunate that I’ve been allowed—within the band, but also with the amount of great gear that is available now—to do the things that inspire me and make me happy. I’ve been very lucky.

Longtime fans probably feel like they have a handle on the guitar dynamic between you, Thom, and Jonny, but what are the most salient differences from your standpoint?

If you want to reduce it to its simplistic terms, I think Thom is a great rhythm guitarist—an amazing rhythm guitarist. Jonny is a great lead guitarist. And I’m sort of in between. I’m the sweeper. I sweep up the shavings. I do a bit of rhythm, I do a bit of textural stuff. A lot of the time, if a song’s being written on guitar [by Thom], then there’s already a rhythm part there—there’s a whole lot of room taken up. If he’s written with Jonny, usually Jonny’s worked out some kind of part.

By the time it gets to the rest of us, there’s only a certain amount of room left. That’s been good for me—it’s been challenging. At times you go, like, “What the fuck am I going to do?” Ultimately, the band’s not a welfare state. If you don't come up with something that serves the song, then you’re not going to play on it. That’s the bottom line. It’s kind of ruthless in that respect. But that’s also a good challenge, because it keeps you out of your comfort zone.

Do you feel like your journey into pedal experimentation, particularly post-OK Computer, was a natural evolution, a result of an epiphany along the way, or more of a survival measure to find a place in the changing landscape?

It’s a bit of all of those things. Firstly there’s a hunger—I was always inspired by sound. There’s a bit of “that’s what the music needed.” There’s a bit of “that was my space.” And, to be frank, there’s a bit of “now I can afford to buy some pedals.” I remember when we made OK Computer … The Bends started it off a bit, but when we made OK Computer, I was so euphoric really, because suddenly all these things that I felt about sound and that I loved, I could bring into the music. And I think it served the music really well. It was definitely a natural evolution. A bit of inspiration, a bit of fear, a bit of everything.

When you guys were recording OK Computer, did any of you have any inkling what an iconic record it was going to be?

No, obviously not. You can never know how a culture’s going to judge it. But I do know that, when we were making it, I felt like we were making something really magical. There were some challenging times, but overall the sounds were in alignment on that record. When we were making it, some of the takes we did, like “Let Down” and “Climbing up the Walls,” were pretty much live takes. There were these moments when we were like, “Oh my god, did we just play that?”

Of course, you never know. You hope that other people feel that magic that you feel. Obviously the reaction, how it was received, was off the scale, really. It was interesting, because it was like that straight out of the doors. I remember the last time I read a review, it was an NME review, and it gave it 9 out of 10 and said it was an extraordinary piece of work. I thought, well, this is the last review that I read, because I don’t like the way it has an effect on me. It’s pumping up my ego and our collective ego. I think I’ll just quietly not read these anymore. It was extraordinary the way it was received. But, you know, a lot of it’s timing.

A notorious pedal collector, O’Brien says the stomp that’s “just blowing my mind at the moment” is Hologram Electronics’ Infinite Jets, which tracks dynamics, samples your playing, and “reinterprets” it via two channels of infinite sustain.

Do you have any favorite pedal recipes that you’ve come up with—combinations that are the most fun for you to play—or does that change over time?

It changes. I think we’re lucky. We’re living in an era of extraordinary pedals. I have a basic pedalboard that I love. I’ve got a Cali76 compressor [by Origin Effects]. I’ve got a Kingsley boost called the Page. I’ve always got a DigiTech Whammy. I’m big into delays. Catalinbread has done an amazing job with the Belle Epoch Deluxe. It’s [a replica of] the [Echoplex] EP-3. It sounds so great. I also really like what Joel [Korte]’s doing at Chase Bliss Audio. He’s doing some really, really great stuff.

It’s tweak-o-rama with all those DIP switches, huh?

Yes, bonkersly deep. But the one that is just blowing my mind at the moment is the Hologram [Electronics] Infinite Jets [Resynthesizer] pedal. Do you know that?

I don’t.

Oh my god! You have to google it. It’s an extraordinary pedal. Just brilliant.And they’ve got another pedal [Dream Sequence]. That one is off the scale. I’m really getting to enjoy digging deep on that. I also wanted to mention one other thing I’m using, apart from the pedals. I’m using these Audio Kitchen amps by a guy called Steve Crow in London, and they are truly extraordinary. I’ve used them on the road, and they’ve been amazing this last year. I’ve been using them in the studio, and they are extraordinary beasts. Amazing. I’ve got the Little Chopper, the Big Chopper, and the Base Chopper—Nathan East was using that on my session, and he loved it.

Are you using those in addition to the Fender Vibro-Kings you’ve been using since 2011 or so?

Well, our soundman complained about the Vibro-Kings, because they were so loud. I was forced to find an alternative. In doing so, I found these Audio Kitchen amps. Obviously the Vibro-Kings are extraordinary amps, but you know how guitarists are. We like a change sometimes.

Last question: Stereotypically, at least, guitarists are infamously obsessed with gear, technique, “holy grail” tones, and other technical minutiae—I suspect that’s at least partly why you, Jonny, and Thom haven’t been super eager to talk to guitar magazines over the years.

Yeah, totally. You’re right.

If you could collectively grab these kinds of guitarists by the shoulders, give them a bit of a shake, and offer them a bit of advice, what would it be?

Just do your thing. Be original. And be inspired. All the great stuff comes out of inspiration, doesn’t it? A lot of guitarists like to play blues: If you’re going to play blues, dig deep. Try and do something different with it. We were always inspired by people like Sonic Youth—the way they kind of mutilated their instruments, the retuning. We were lucky that post-punk had the golden era of guitarists. People like Johnny Marr, John McGeoch [Magazine, Siouxsie and the Banshees], the Edge—all these people were doing something really, really different and unique, and not necessarily playing the blues. So be different. Be yourself.

Ed O’Brien and his Oxfordshire mates work their way through “Airbag,” one of OK Computer’s most adventurous guitar tracks, live in Milan, Italy, in June 2017.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)