|

|

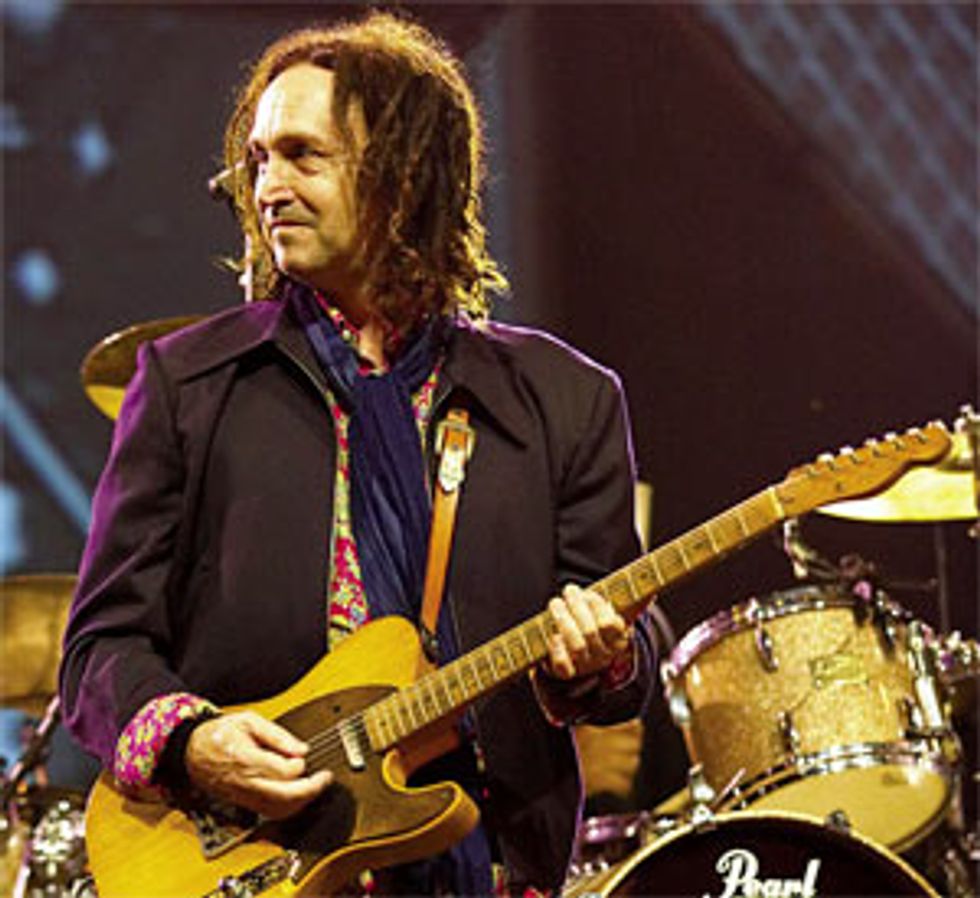

From the beginning, he has been heavily involved in constructing the arrangements for the Heartbreakers’ tunes. As a coauthor, Mike has been responsible for some of the band’s biggest hits, as well as two of Don Henley’s biggest songs, “The Boys of Summer” and “Heart of the Matter.” Time and time again, he has demonstrated that great songs are all about melody, construction and amazing guitar sounds. Like George Harrison before him, Mike reminds us that no matter what guitar he is playing – be it 12-string, slide, acoustic or electric – the most important thing is to always respect the song.

To celebrate the 30 plus years of the Heartbreakers, director Peter Bogdanovich put together a high-quality DVD boxed set called Runnin’ Down a Dream, which has the potential to go down as one of the best rock n’ roll documentaries ever created. In the film, Mike displays a sense of candor and comes across as both caring and wise – qualities which also emerged in our interview. Shortly after our chat, it was announced that Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers would be joining a small but elite class of musicians who have been chosen to perform at the Super Bowl halftime show.

Hi Mike, and thank you for taking the time to speak with us today. First off, congratulations on the new DVD, Runnin’ Down a Dream; Peter Bogdanovich did a fantastic job on it and the amount of old footage is amazing. It’s a great close-up of the band’s 30-year career, but I still get the feeling that there’s plenty ahead for the Heartbreakers. Are you guys planning on touring in 2008?

Hi Mike, and thank you for taking the time to speak with us today. First off, congratulations on the new DVD, Runnin’ Down a Dream; Peter Bogdanovich did a fantastic job on it and the amount of old footage is amazing. It’s a great close-up of the band’s 30-year career, but I still get the feeling that there’s plenty ahead for the Heartbreakers. Are you guys planning on touring in 2008? Yes we are – we’re planning on putting a tour together for next summer.

I understand you have a new side project called The Dirty Knobs. Can you tell us about that? Are you guys doing mostly original stuff?

We do mostly originals, but do the odd cover now and then, like The Beatles’ “She Said, She Said,” or something by the Kinks or Chuck Berry – older stuff – and then arrange it to fit our group. The Dirty Knobs is myself and another guitarist named Jason Sinay, Matt Laug on drums and Lance Morrison on bass. It’s all about fun, it’s a very spiritual band, and we’re not concerned about trying to get a record deal.

Have The Dirty Knobs been in the studio, and if so, can we expect a release anytime soon?

We’ve recorded a lot and it’s great stuff, but I don’t know that we want to take on the industry right now because we’ve got such a good thing going. I almost don’t want to bring that energy to it, because it is such a great way to just go out and play.

How did you develop your style of playing? Did you take lessons or learn mostly from records?

Back then we didn’t have cassette players or anything, but I would sometimes slow the records down and listen real close and try to figure out how the guitar player was doing certain things. I had a couple of guitar books too. There was one I had, I wish I still had it – it was How to Play the Guitar with Carl Wilson [of the Beach Boys], and it had pictures of his hands. I met him several years later and said, “Hey, I had your book” and he was sort of blown away, and said, “Oh, my Dad put that together!” So I got a couple of ideas on how to finger certain chords from that, but most of it I just picked up by ear, off the records.

So no formal lessons?

No, I never did, but when I was real young – I guess I was in sixth grade – my parents got me some accordion lessons in school, so I kinda learned a little bit of basic theory from that. I can read, really painfully slow, but not enough to actually use it.

Were you just playing with an acoustic at that point?

My mom got me my first guitar, a Harmony acoustic for $30 that was unplayable. The strings were so high and I would struggle like crazy and my fingers would bleed trying to play the damn thing. Then I went to a friend’s house one day and he had a Gibson SG, and I could not believe how easy it was to push the strings down. So I started on that Harmony acoustic and later on my Dad got me my first electric guitar, a Goya. I wish I still had those, but I gave them away over the years.

What were you playing the Goya through?

What were you playing the Goya through? My first amp was my record player. My dad was an electrician and he had a record player that was all in pieces, so I just plugged my guitar into that.

Did you have a group at this point?

I was just trying to learn how to play; I’d get together in the garage with friends occasionally and try to play “Louie, Louie” or something like that. I didn’t really get a group together until I went to college; then I met Tom and joined his group called Mudcrutch.

In the movie, it shows that Mudcrutch left Florida in 1974 for the West Coast, and within a few days you had several record contract offers and eventually signed with Denny Cordell – that seems unbelievable, especially in this day and age.

Yes it was, but it was a different time back then, and record companies were a little more concerned with artistic development and less concerned about the bottom line. Especially Cordell, who really had an artistic vision and who was really helpful to us, as they touch on in the film. He had made lots of records to be respected, and he really saw a germ of talent in Tom’s songwriting. He really nurtured it, and kind of helped us filter out what was good and what wasn’t good about what we were doing. He was tremendously helpful in getting us on the right path.

That first Heartbreakers album has some great guitar tones on it – do you remember what you were playing?

That first Heartbreakers album has some great guitar tones on it – do you remember what you were playing? Most of the guitar tones on that first record were Tom playing my ’64 Stratocaster and me on a ‘50s Broadcaster through a tweed Fender Deluxe and a [1970s] Fender Super Six, which were in the Shelter Records studio.

That Stratocaster was something I had gotten for $200, and I didn’t have the money, so someone had fronted it to me. I did like the guitar sounds on that record, especially the crunch of that tweed Deluxe, which is like the one Neil Young uses that has such a beautiful distortion.

I saw your most recent tour last summer and know that you are using dozens of guitars live, but what''s your current stage amp setup?

We have a combination of things; on the last few tours, we brought the [Vox] Super Beatles back after having retired them for a while because they are really loud, and as we got older it was harder to sing over that volume. We brought them back because we missed some of the tones that we used to get from them. Those Super Beatles are on stage now - I''m not actually playing through them but Tom does on a couple of songs. Behind them are the things that we are actually using in the mix.

Right now my favorite setup, which I kinda found with my little band in the clubs but I use onstage now with the Heartbreakers, is a tweed Deluxe and a blackface Fender Princeton together behind the Super Beatle, and an isolated Vox AC30 that I have backstage in a box. The guy up front can pull up any of those amps that fit the room that night, but mostly it''s the blackface Princeton and the tweed Deluxe, which is a ''59. Those two amps sound really great together.

You came out of the era of the big guitar hero, but you managed to avoid all the excess wanking that made a lot of their records seem self-indulgent and ultimately sound very dated. I have always likened you to a George Harrison or Keith Richards type of player; someone that was always very sympathetic to playing exactly what fit the song versus showboating.

We came up out of Florida and at that time, there were a lot of Allman Brothers, Lynyrd Skynyrd-type bands. And we liked that stuff, but what we loved even more than that was early Beatles and the Stones - three-minute songs, with good guitar parts and not necessarily long guitar solos. We just preferred that style of music, and figured out early on that all of those other bands were trying to sound like the Allman Brothers, and we didn''t want to do that, we wanted to do what we liked. And that''s really always been our approach!

How do you approach soloing? Do you work stuff out beforehand, simply let it flow, or is it a combination of both?

The song comes in, and the purpose is to serve the song, not the guitar part. You used George Harrison and Keith Richards as examples; really cool rhythm parts played between the vocal, with a short solo that says something then gets out of the way for the next vocal. It''s a challenge to make your statement in a short amount of time, but I prefer that challenge as opposed to just stretching out. We can do that too, and nowadays we will stretch out a few things, but anytime that it starts to drift away from the song, we kind of lose interest.

What really comes across in the new DVD is that besides the respect the Heartbreakers have for their music, there seems to be a genuine love for each other, too.

What really comes across in the new DVD is that besides the respect the Heartbreakers have for their music, there seems to be a genuine love for each other, too. I think that''s right - that''s what hit me when I saw the film. It was like, "God, we really like each other!" [laughs] I mean, guys don''t sit around saying, "Hey, I love you man," but when I saw the film I thought, hey, there really is a love here, and we stuck together through a lot of hard times because we really have strong feelings for the music we make together. And it''s not an act, it''s true love.

Your musical relationship with Tom obviously goes way beyond the typical rhythm/lead classifications. How do you decide who is going to play what?

Typically it would go one of two ways; if it''s a song that Tom''s written on his own, he''ll bring it in, play it down and we''ll listen to it, and start to join in as we begin to understand what he''s doing. I usually come up with a complementary rhythm part to what he''s singing. When we come to a solo, we typically don''t work that out, but we like to record them as you''re discovering them - just sort of make something up. And usually the first or second idea you come up with is the best one. You listen to that and kind of edit it a bit, sticking with your first inspiration.

Another way we''ll go is if it is a song I''ve written, I''ll bring in some music and Tom might write lyrics to it, and sometimes in that music, the guitar parts have been already worked out. Then we''d cut the record and try to recreate what we liked about the demo. Most of the solos on our records are just off the cuff and sorted out from that first inspiration. For instance, on "Breakdown," we were cutting the song and it went on for about six minutes, and I was playing along, trying a couple of different things, and by the end of the six minutes, I was drifting off and hit on that melody riff, which I was playing on a slide. Everybody liked that line, so I learned it and went back and played it at the top of the song. That''s an example of something that was off the cuff that was then edited and fit in because it made sense.

You''ve co-authored some of Tom Petty''s biggest songs, as well as other hits. How do you approach your writing - do you come up with a riff first or a lyric?

You''ve co-authored some of Tom Petty''s biggest songs, as well as other hits. How do you approach your writing - do you come up with a riff first or a lyric? Well, I''m always writing, even when I don''t have a guitar in front of me, I''m always trying to keep the antenna open to any idea that might come, at any time. It''s a mysterious thing - writing is a gift, and it''s a sort of channeling. Sometimes it''s not even coming from you, you are just sort of open and things come to you. A lot of times, it will just happen if you are in the right state of mind, the ideas just come.

Sometimes if I''m stuck, I will play a song that I like, a Beatles or Stones song, to get me in the state of mind to just open up, to have a pivotal point that I can key from. Other times, I might put on a song I''ve heard a million times and listen. Or I might hear something on the radio, and think, wow, that''s a great chord or sequence, and I''ll sit down and learn it, and as I''m learning it, I might get an idea to do something like it but different - I might play the chords backwards, or take a lick and stick it over a different chord, and that will lead me into something that''s mine, which was inspired by something that turned me on. Sometimes you''ll just hear a chord, you''ll sit down and learn it, and you think, this is a great chord, and you can just write a whole different song starting with that as your foundation. That''s the beauty of writing - you can tap the soul of the thing that inspired you and find a way to make it your own. It''s hard to talk about it because it''s very mysterious.

How do you think your playing has changed over the years?

Tom said something in the film about when he first met me and said, "He played as good then as he does now." [laughs] What''s interesting is that musicians get to a point where you get pretty good, and that''s pretty much who you are, at least in the kind of music we''re doing. You can look at Clapton, Jimmy Page or George Harrison - once they started establishing their talent, I really don''t know how much they improved. So that''s probably where I''m at, too. I play the guitar all of the time, but I''m not interested in playing faster, or more technically. I always try to work on my rhythm and my tone and my song sense - that''s just something that I focus on and always try to get better at. But am I better than I was? I don''t know. In some ways I''m the same as I always was. I think I''m more mature and may make better choices in my composition than I might have earlier.

In your 30 plus years as a Heartbreaker, you''ve had some lineup changes in your rhythm section. How does playing with Steve Ferrone compare with previous drummer Stan Lynch, who left in the nineties?

In your 30 plus years as a Heartbreaker, you''ve had some lineup changes in your rhythm section. How does playing with Steve Ferrone compare with previous drummer Stan Lynch, who left in the nineties? Stan and Steve are completely different. Stan always played with more of a "member of the band" mentality. He was always just part of the band and a friend from early on, and there was that kind of bond that is unique to him. He was essential to helping us find our original sound and he was part of that sound. The way he played really complemented that, and you can''t take that away from him. He''s a great background singer and he was really important on that level early on and for many years. Stan was really great live; he had energy and power and confidence, and was a cheerleader, too. He would get us up when we were down, and he was a real strong and emotional force, especially live where his energy was really powerful. We got to the point in the studio where we got really pissy with each other and it got really uncomfortable for him - it was time for him to go and do the other things that he wanted to do.

Steve Ferrone came in, and he''s never been in a band long-term until us. He''s more of a session guy, and his approach is very professional and accurate, and his time is really good. He''s great in the studio because he''s very consistent and he doesn''t get emotional or wrapped up in it. He brings sort of a "studio cat" mentality - he does his job, and you don''t have to think about whether the drums are going to speed up or slow down. He just gets his job done and you can focus on the song and not get hung up on that. He''s a sweet guy, and he brought a lot of professionalism and accuracy, and Steve is great live, too. But it''s hard to compare two different human beings; they are both great in their own way and equally talented in different ways.

And of course, Ron Blair was originally your bassist, then Howie Epstein and now Ron again.

Ron was a founding member and was very instrumental to us finding our original groove, sound and vibe, and that''s irreplaceable; it was sad when he left. Howie came in and was a great harmony singer, which was the main thing he brought to us. Howie played the bass more like a guitar player or a singer who was accompanying his voice, and Ron was more like a bass player in terms of his groove and feel. And they''re both valid in their own way. I don''t prefer one over the other - they are both equally talented. It was of course very tragic and unbearably sad that Howie passed away, but we were pleased to bring Ron, who was part of our original soul, back. [After leaving the Heartbreakers] Ron and I stayed in touch for many years, played in the studio and were very close. When Howie''s leaving left a void, and it was like "Oh, now we have to audition some guys," and if that didn''t feel good, we probably would have disbanded rather than do that.

Was Ron in a band during those interim years?

No, the most playing Ron did was with me; he''d come over and cut songs in my studio. We stayed close and his chops were up, so I brought him in and suggested that he''d be our best choice. Tom was pleased to see that Ron had improved and still had soul, and it all worked out.

I understand you are currently working on a new album with Rick Rubin and Neil Diamond - what can you tell us about that?

I think it''s coming out next year. It''s all acoustic and it''s similar to the last record that Rick did with Neil Diamond. It''s a challenge because there is no rhythm section; it''s me, and Smokey Hormel, this guy Matt Sweeney, who is really good on acoustic guitar, Benmont [Tench] and Neil. Once again, it''s Neil''s songs and Neil''s feel, and we''re making him play the guitar, which he''s starting to get back into again, and we''re playing around the feel and the songs, trying to complement his guitar with acoustics. It''s really fun and it''s a real challenge, and working with Rick is always inspiring. Rick is brilliant; he loves music, he loves getting it right, he loves good songs and I''ve always loved working with him.

Are there any current players you are listening to these days?

Are there any current players you are listening to these days? I struggle to think of someone recently - I tend to gravitate toward older players that influenced me originally. I love J.J. Cale, but he''s been around for years, and I like Mark Knopfler, who I think emulates J.J. I do like Derek Trucks, I think he''s amazing. A lot of the new bands, though, have a different approach to guitar than back when I started. I don''t like flashy stuff - I like songs with good melodies and it seems that no one is doing that these days.

What is your take on the state of rock n'' roll today?

It''s alive - you can''t kill it. When I play with my little band at clubs, there are moments that make me remember why I started doing it, playing in a room with 100 people or whatever, and there are moments that are as pure as anything in its own way. We may not have the songs or the hits, but there is a purity in a room with a band that''s got a sound and is playing to a small group, and it''s all happening in this little room - to me, that is where rock n'' roll is still alive. It''s hard for me to put that into words, but to me it''s like a religion, it''s just gotta be, and it always will be, because there is nothing like it. It''s the best medicine for the soul that''s ever been.

From having numerous platinum albums and Grammys to being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2002, what do you feel has been the highlight of your career?

[pauses] Well, there have been lots of high points. I went and saw this play called Jersey Boys, about the Four Seasons, and at the end of the play, the actor that played Frankie Valli said something that rang true. They asked him the same question, what he considered the high point to be, and his answer was, "The high point for me was when we were standing under the street lamp, and we found our sound, and we knew it was all ahead of us, and we knew what was going to happen." And for me, I had that same feeling when we cut "American Girl" in the studio, because we found a sound and a vibe that was ours, and I remember feeling that we had found something really special that no one else could do, and this can be us, this can identify our trip. I could feel it. It hadn''t happened yet, but I could sense that, "we''ve gotten something here." And that was probably the high point for me. There''s been other successes here and there.

That''s the understatement of the year!

Really, when I heard that character say that, it was so true. "American Girl" was such a big spark, and when we realized that, we knew we had something!

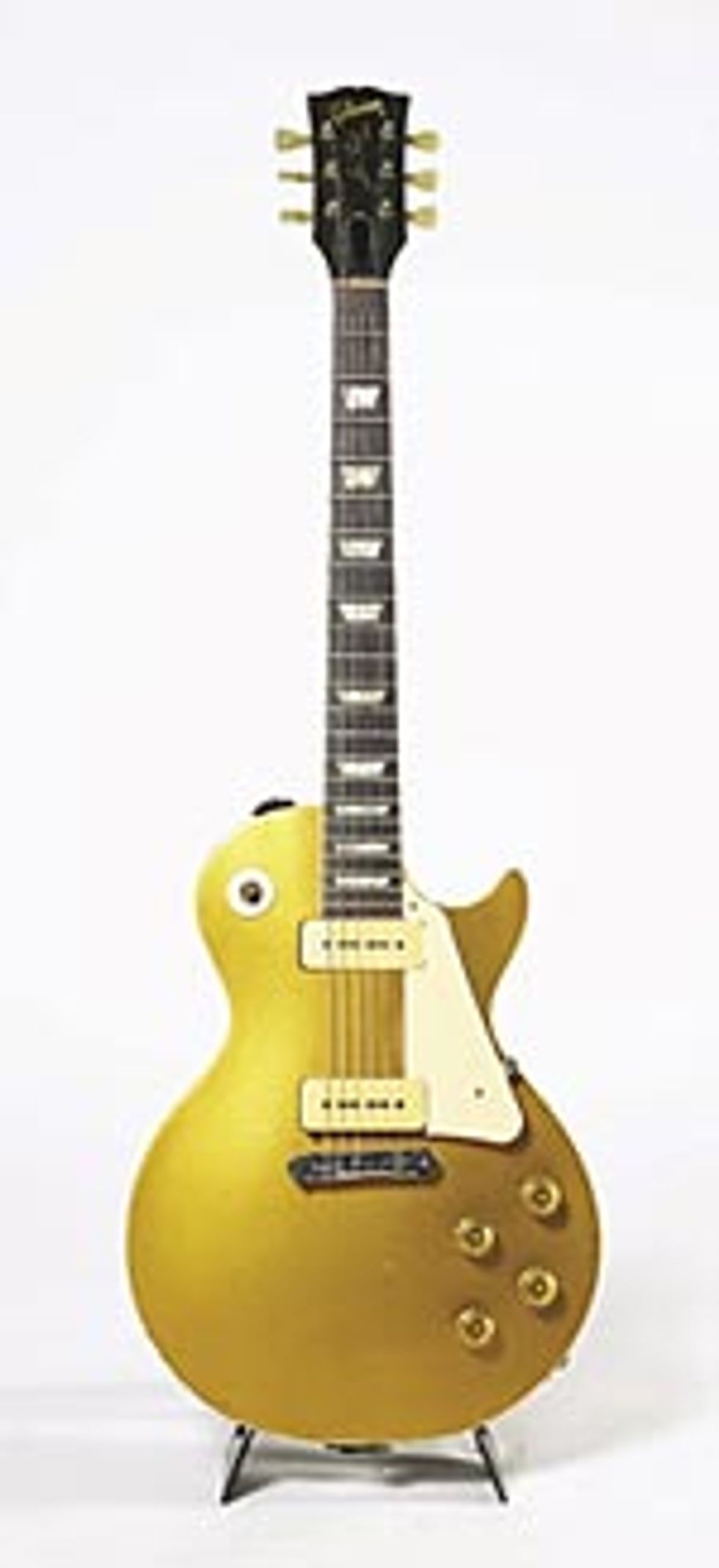

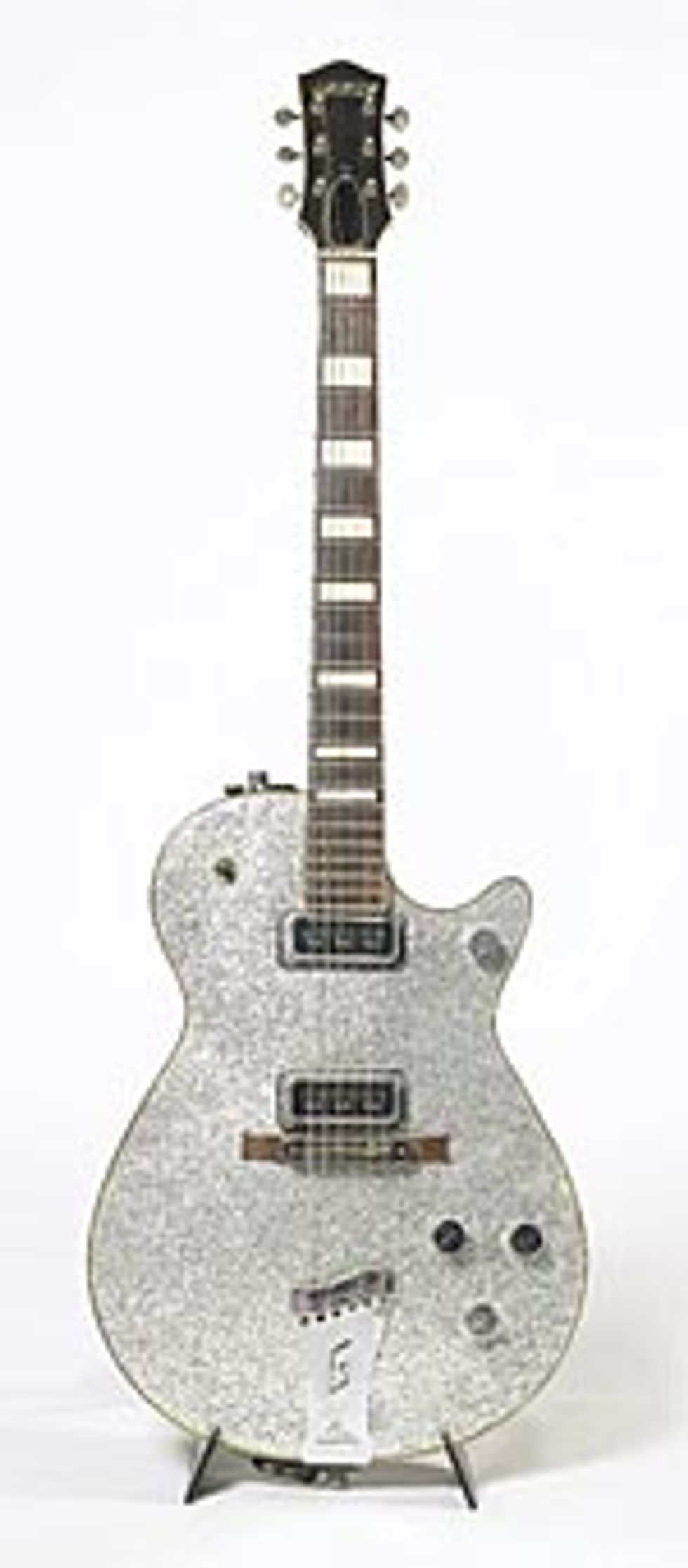

| Mike’s Gearbox Note: Being an avid collector of vintage guitars and amps, the following is only a small sample of some of Mike’s favorite gear (some of which is pictured above).

|

Mike Campbell

thedirtyknobs.com

tompetty.com

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)