“I always had it in the back of my mind,” Mike Campbell says thoughtfully, from his home in the hills outside Los Angeles. He’s taking a moment to savor what it felt like to go back in time and listen to the raw tapes of a now-legendary residency. “Playing the Fillmore was exhilarating for us. I knew then that it was really good, and I would always look forward to the day we’d pull it out again. And when we did, I was pleasantly surprised that it lived up to my expectations and my memory. There’s a lot of kinetic energy and interplay—and fun. We were having fun, you know?”

At the time, fun had been a bit overdue for Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, and elusive for Petty in particular. He had just finalized a bitter divorce with his first wife and was living in seclusion in a “rundown shack,” as he called it, in the Pacific Palisades. He’d only just released his solo masterpiece, Wildflowers, in November 1994, and, the following year, toured the country behind it with the Heartbreakers. He and the band had also backed Johnny Cash on the country legend’s Rick Rubin-produced album Unchained, so there’d been plenty to celebrate. But as cathartic as Wildflowers had been for Petty, he was still working through more than his fair share of pain and heartbreak.

Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers - Listen To Her Heart (Live at the Fillmore, 1997) [Official Video]

The answer, as it turned out, was to set up shop at the Fillmore in San Francisco—a storied venue he felt a deep connection to, yet somehow had never headlined. “I just want to play,” Petty told the San Francisco Chronicle’s Joel Selvin shortly before the band’s opening night on January 10, 1997. “We want to get back to what we understand. We’re musicians, and it’s a life we understand. If we went out on an arena tour right now, I don’t think we’d be real inspired. We’ve made so many records in the past five years, I think the best thing for us to do is just go out and play and it will lead us to our next place, wherever that may be.”

“We’ve made so many records in the past five years, I think the best thing for us to do is just go out and play and it will lead us to our next place, wherever that may be.”—Tom Petty

“Some of this stuff just felt like we were in rehearsal,” Campbell marvels. “You know, somebody might say, ‘Hey, you know that Dave Clark Five song? Let’s try that.’ And we’d just go into it. The Fillmore really felt like that sometimes. We don’t know this song that well, but we’re just gonna go into it and see what happens. And more often than not, magic would happen.”

In fact, the magic unfurls with astonishing regularity. “Mary Jane’s Last Dance”—originally a one-off tracked between sessions for Wildflowers that turned into a TPHB hit, as well as drummer Stan Lynch’s last stint with the band before Steve Ferrone, who gets his trial-by-fire on Live at the Fillmore, stepped in for good—takes a kaleidoscopic turn over the course of 10 minutes, with Campbell laying into a hypnotic wah solo, followed by Petty’s own slashing foray on his beloved Torucaster, built by former Fender luthier Toru Nittono. “County Farm,” by contrast, is a wild dive into hardrocking blues, building and then ebbing in waves punctuated by Petty’s own inspired wah solos, Campbell’s tasteful slide work, and keyboardist Benmont Tench’s barrelhouse Rhodes piano. It’s of a piece with John Lee Hooker’s “Boogie Chillen,” another extended jaunt that features Hooker himself, who literally walked across Geary Boulevard from his famed Boom Boom Room hangout to join the Heartbreakers onstage, along with guitarist Rich Kirch from his own band.

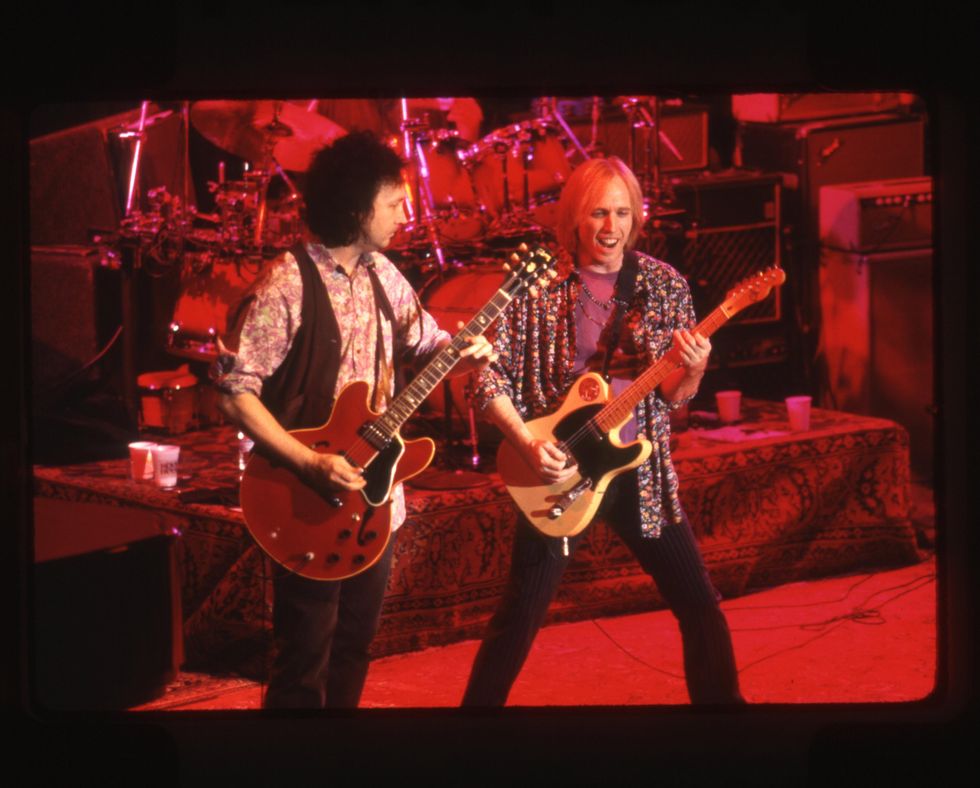

Petty and Campbell rock out during their Fillmore residency, with a wall of Vox and Fender amps behind them.

Photo by Steve Jennings

The just-released Live at the Fillmore (1997) finds TPHB, as they’re lovingly known to their fans, trailblazing their way to a new level of versatility. Compiled from multi-track recordings of the last six nights of the band’s 20-date residency, the heady and hefty box set boasts nearly 60 songs—many of them covers, including classics like Chuck Berry’s “Around and Around” and a rowdy 10-minute version of Van Morrison’s “Gloria,” as well as more semi-obscure gems like the Zombies’ “I Want You Back Again” and J.J. Cale’s up-tempo “Call Me the Breeze.” It’s a testament not only to Petty’s vaunted and deep knowledge of rock ’n’ roll and all its unruly history, but also to the Heartbreakers’ ability as a unit to grasp a moment, whether they’d played a song a hundred times together or just once, and sear it into memory.

All this attention to detail is no surprise, really, considering Petty and Campbell are well-known tonehounds whose daunting arsenal of vintage gear became part of their identity as a team. Their shared language as players also seems to coalesce with a new sense of vitality during the Fillmore run.

The last six nights of 20 evenings of concerts at the Fillmore, where Petty and his band celebrated their deep roots, were recorded for the recently released boxed set.

Fittingly, the Heartbreakers also seem to feed off the energy of the Fillmore audience. And as much as Live at the Fillmore is a paeon to the small-capacity club roots of rock ’n’ roll, the set manages to elevate guitar worship to dizzying heights, precisely as a result of that intimacy. There’s a beautiful restraint in Petty’s largely solo acoustic version of the early hit “American Girl,” and he brings a stunning power to his “Angel Dream,” with the band quietly and confidently shadowing his every move (especially the late Howie Epstein, whose harmony vocals are as vital to the band’s sound as his sinewy bass lines). Even a cover as far afield as Bill Withers’ “Ain’t No Sunshine” sounds completely natural in Petty’s capable hands, especially during the “I know, I know” breakdown, when he smoothly cues Ferrone and the rest of the band back into the song’s underlying groove.

“Toward the end of it, we were a finely oiled machine,” Campbell jokes. “We had a lot of confidence. It’s like a musical conversation going on between us. That’s the best way I can describe it. When we first met, Tom and I had an instinct that if one guy would play a rhythm or a lick, the other guy just knew exactly what to do to complement it. We just had that telepathy thing—and with Benmont, too. You hear the tones coming from the piano, and your instincts just tell you, ‘Well, you shouldn’t play a big loud note here. You should let it breathe for a second, and then answer it.’ You really have to concentrate and listen to the other guys in the band. Don’t just go off on your own ego.”

Mike Campbell's Gear

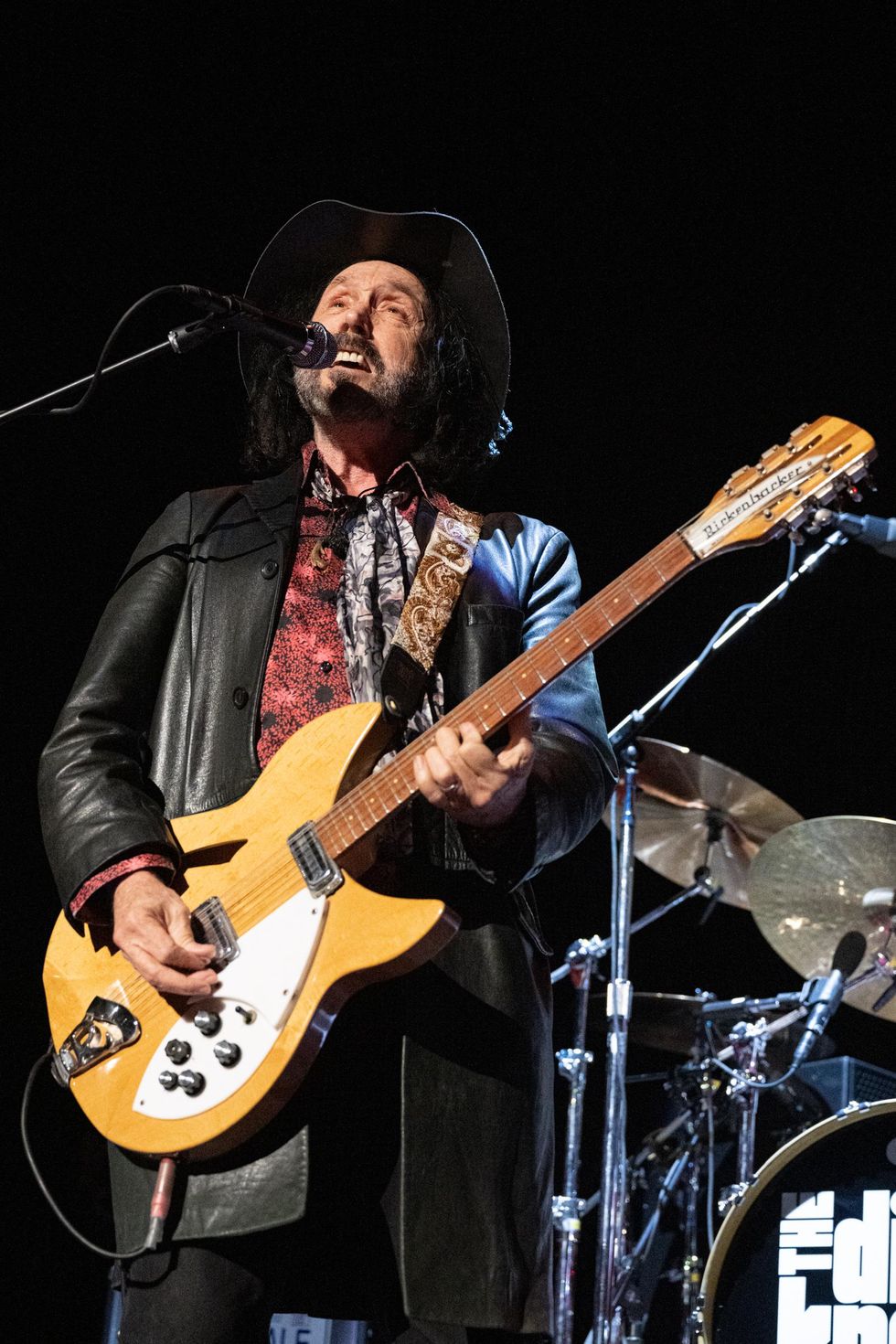

Mike Campbell onstage with his current band, the Dirty Knobs. When Roger McGuinn guested with the Heartbreakers at the Fillmore, Campbell acknowledged him as “the king of the Rickenbacker [12-string], so I didn’t want to do anything to get in the way of that. I might pull mine out somewhere else in the set, but at that moment, that’s his space.”

Photo by Jim Bennett

Guitars

- Fender Telecaster

- ’65 Gibson Firebird

- Gibson Les Paul

- Gibson ES-335

- Rickenbacker 360/12

- Rickenbacker 615 Jetglo (painted black by original owner)

Amps

- ’63 Fender Princeton

- ’54 Fender Tweed Deluxe

- Blonde Fender Bassman

- Kustom 250

- Vox AC30

Effects

- Vox wah

- Way Huge Camel Toe

When none other than Roger McGuinn joins them for a mini-set of songs by the Byrds, he puts the band’s active listening to the test. “Eight Miles High” features McGuinn, Petty, Campbell, and Scott Thurston—the Heartbreakers’ “Swiss Army knife” and secret weapon on rhythm guitar—all playing distinctive parts that mesh together with a startling seamlessness. It’s a revelation that mix engineer and co-producer Ryan Ulyate, who had worked with Petty and the band since 2006’s Highway Companion, thoroughly enjoys accentuating.

“There’s a great McGuinn-Campbell face-off in that,” he points out. “McGuinn is doing the solo on the 12-string, and then Campbell just jumps in, and he’s a lot darker. And really, that’s the whole point. What the Heartbreakers brought to the stage always complemented each other, and because they have those distinct tones, you hear the blend; plus you hear the personality of every player. Even when you’ve got three parts going at the same time—and in this case, with Roger, four — you can still hear the different personalities. They were just really good at that.”

Campbell still refers to McGuinn’s appearance with humble reverence. “You know, we worship Roger,” he says. “The Byrds and that sound were a big influence on me, probably equal to Chuck Berry, so we were thrilled to have him on the show. And he’s the king of the Rickenbacker [12-string], so I didn’t want to do anything to get in the way of that. I might pull mine out somewhere else in the set, but at that moment, that’s his space.”

Tom Petty's Gear

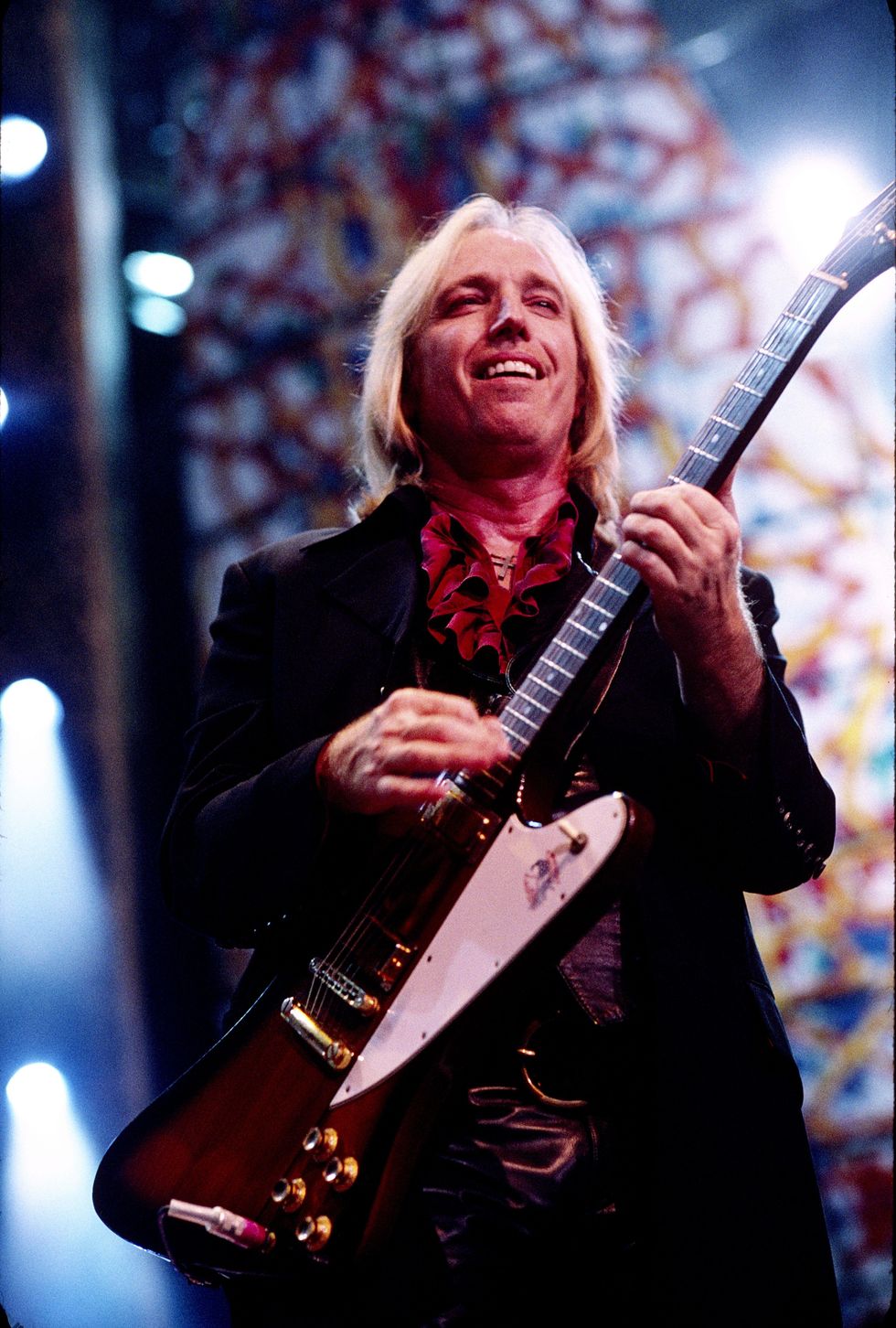

Petty onstage with his Firebird, a lesser-seen member of his armada of classic guitars.

Photo by Ken Settle

Guitars

- Fender-style “Torucaster” (purchased in 1981 at Norman’s Rare Guitars in Reseda, CA)

- Gibson Firebird

- Gibson J-200 acoustic

- Rickenbacker 330

Amps

- Blonde Fender Bassman

- Fender Vibratone rotating speaker

- Vox AC30

Effects

- Boss RV-3 Digital Reverb/Delay

- Ibanez Tube Screamer

- Vox wah

- Way Huge Red Llama

And once again, this is what defines the ethos of the Heartbreakers, and why they remain a distinctly American rock ’n’ roll band. The respect for the canon (Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Elvis, and plenty more), the stripped-down simplicity, the complete lack of selfishness, the unified understanding that each member contributes only what’s best for the song, and to have a hell of a lot of fun doing it, so the audience feels pulled in for the full ride—all these qualities reach their peak at the Fillmore shows.

Petty himself thought as much when journalist Paul Zollo told him, in 2006, about a bootleg he’d heard of the Heartbreakers’ version of the Rolling Stones’ “Time Is on My Side,” which makes the final cut for Live at the Fillmore. “I’ve never heard that,” Petty admitted at the time, “[but] over those 20 nights, we played well over a hundred different songs. One night we played four hours, which really isn’t like the Heartbreakers. But we just got into a groove. The encore was an hour and a half, and it was great, because it was intimate. Those things really stretch you, and they let people get a really good look at the group and what we’re about. You can do things in a smaller theater that you can’t do in a coliseum, so it’s kind of liberating.”

“Tom and I had an instinct that if one guy would play a rhythm or a lick, the other guy just knew exactly what to do to complement it. We just had that telepathy thing.”—Mike Campbell

It’s easy to speculate that a renewed sense of creative freedom, spilling over from the Fillmore run, provided the spark for later Heartbreakers albums. And 2010’s Mojo, in particular, with its overt nods to a bluesier and more improvised-from-the-floor delivery, comes to mind. Campbell doesn’t name any specific recording that reaped the benefits of the band’s growth during that incredibly fruitful month of shows in early 1997. Instead, to him the afterglow feels much more overarching, lasting, and profound.

“When we started out playing, we weren’t playing arenas, you know?” Campbell says. “We were playing for two hundred, a thousand people, and the joy of just plugging in and hearing your sound, and hearing the other guys—a rock ’n’ roll band is amazing that way. You get everyone in a room, you all plug in, you go one-two-three-four, and this thing happens. And it’s like I said, the Fillmore was exhilarating for us, to get back to that approach to music. It was just very spiritual and very inspiring.”

Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers - The Fillmore House Band - 1997 (Short Film Part 1)

This is the first part of a tantalizing two-part mini-documentary on TPHB’s ’97 Fillmore stand. The band was geared up for an intimate series of dates that allowed them to stretch beyond the creative limitations of a normal tour—exemplified by Petty’s stripped-down acoustic performance of “American Girl,” for starters.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)