The term “the blues” can mean several things: a style of music, a sense of being downtrodden or neglected, a feeling of melancholy or impending doom. Mark “Porkchop” Holder is intimately familiar with all three of these definitions—perhaps more than he would like to be—but that serves him well on the debut album with his new band MPH, Let It Slide.

In fact, Holder has soldiered through such a mean case of the blues that the very existence of Let It Slide, which is credited only to him on its cover, is something of a miracle. Just a few years ago, Holder, who is open about his struggles with mental illness and addiction, spent roughly a year living in the woods of Northern California in an RV with no electricity or running water, feeling too paranoid to interact with anyone.

But after some months in a psychiatric hospital regaining his bearings, Holder reemerged, revitalized and ready to bring his music to the world again. In April 2016, he began to record Let It Slide, and the results were so powerful that a few months later he signed a deal with Alive Naturalsound Records, a respected independent label that’s been home to a wide range of top-shelf artists, from the Black Keys and T-Model Ford to the Plimsouls and Beachwood Sparks.

Originally from Chattanooga and residing there now, Holder—the son of a 20-year Navy man who became a Baptist preacher—lived all over the South growing up. He started making waves in Nashville in the mid-aughts when he was playing in the punk-blues outfit Black Diamond Heavies. (The band continued as a two-piece after Holder left in 2006, and are currently Holder’s label mates on Alive.) All the while he was immersing himself in the blues canon, studying legends such as Robert Johnson, Mississippi John Hurt, Mississippi Fred McDowell, John Lee Hooker, and others. For a couple years, Holder spent most of his days busking in Nashville’s Lower Broadway tourist district, perfecting his skills as a solo performer.

to talk to anybody.”

Let It Slide marks the first time since his Black Diamond Heavies days that Holder has dedicated himself to the band format, after years of predominantly performing solo. He enlisted Chattanooga-area music scene veterans Travis Kilgore on bass and Doug Bales on drums, both of whom play on the record and have been touring with Holder.

Holder’s recent struggles provided fodder for one of the album’s strongest tracks, “Disappearing,” the lyrics of which Holder wrote on a napkin while he was in the hospital, gravely ill and longing for a visit from the woman he’d been seeing. The lyrics paint a haunting picture of a man at the end of his rope: “They say that all things must pass / Well I hope that it’s my time at last / Come and see me child, I’m fading fast / Disappearing, carry me away.” A propulsive drumbeat creates a sense of urgency, as does Holder’s guitar work, which features a lot of flat-fifths that heighten the sense of doom.

“My Black Name” is a classic blues lyric about dealing with a bad reputation—and not giving a damn what other folks think. It features the nastiest guitar tone on the album, reminiscent of some of Dan Auerbach’s sounds with the Black Keys.

Holder lays down some of his finest guitar work on “Headlights.” He channels a little bit of both Keith Richards and Mick Taylor, and with some cowbell in there to boot, the track sounds like a nod to vintage early-’70s Stones. Holder’s reimagining of the popular folk tale “Stagger Lee,” meanwhile, leans toward classic Zeppelin—particularly the reverb-drenched harmonica parts, which he also plays.

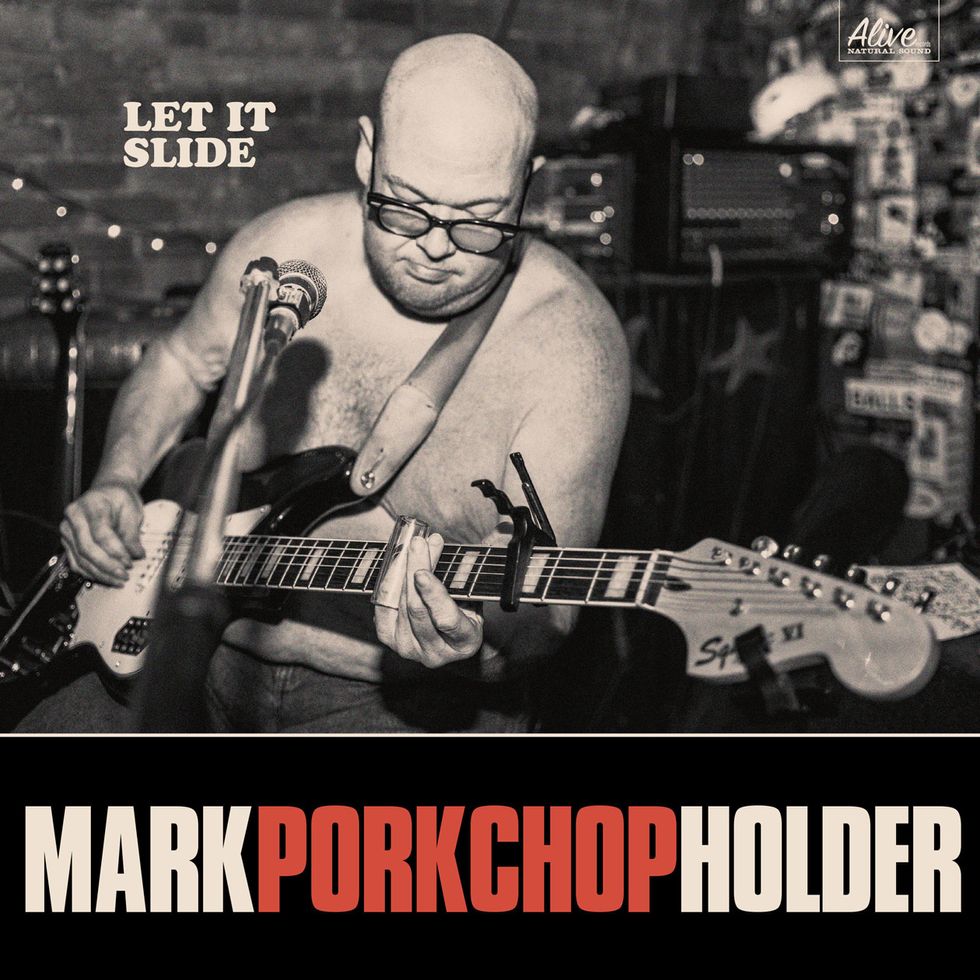

Although Holder used his National Tricone Baritone on Let It Slide, he travels with the less-rarified Fender Squier Bass VI, which he plays on the album’s cover photo, to generate low and ferocious slide tones in concert.

Let It Slide is not only an incendiary debut from a budding blues-rock force, but a moving testament to one man’s triumph over some very formidable personal demons. Holder recently took time while touring the Northwest to speak by phone with Premier Guitar about the new record, his musical evolution, and his internal battles.

Where did you record Let It Slide?

I recorded it at a studio in Chattanooga called Tiny Buzz, owned and operated by a fellow named Mike Pack. He’s an old friend. He was the engineer on the first Black Diamond Heavies duo album—the two-piece album they did when they got signed to Alive. He’s a great producer and engineer. He coproduced.

You’ve played solo for a while. How long has it been since you played with a band?

I’ve been playing by myself for years. I’ve done occasional things with a rhythm section. It’s funny … these two guys—Travis Kilgore and Doug Bales—had not played together, but each one of them had played with me separately prior to doing this album.

How’s the tour been going?

Really well. We’ve really enjoyed the shows. We’ve had a really nice time playing major cities—Los Angeles, Seattle and all that—but at the same time we played a gig the other night on an island that has 2,000 people on it in Puget Sound. Rode the ferry out there and played for those folks.

Holder wears the hollowbody Peavey JF-1 he played on Let It Slide. Recently the guitar has been supplanted onstage

by a Gibson SG. Courtesy of Alive Naturalsound Records

One thing that struck me about the record is that you have that gutbucket, juke-joint, slide-guitar sound, but for most of the songs on the album, you didn’t fall back on the straight-up 12-bar form. Did you intentionally try to take the blues in different directions?

No. Really, it’s just that I’ve spent a whole lot of my life trying to become a blues player I would want to hear. I’d never taken my own songs as seriously as sort of learning the canon. And I just realized that maybe the time had come to do that. I wasn’t concerned about making a blues album. I figure that you’re going to hear some blues in whatever I do. So, I tried to be a little freer, and really was trying to pretty much make a rock record.

And after a while genre terms almost become meaningless.

Yep. What did Johnny Winter play? Was he a blues musician or a rock musician?

Exactly. What made you decide to start the album with a 30-second snippet?

That was actually Mike Pack. And I didn’t even know what he was doing. He said, “I’m going to roll tape for a second, play something.” One of the bands that came up while we were recording this thing was Black Sabbath. And their little excerpts they do sort of inspired the idea of doing that.

I really enjoy “Disappearing.” It’s got some of that dark flat-fifth thing, and I really dug the solo on the outro. What inspired that song?

I was seeing a woman, and I was in the hospital. She was separated from a doctor that worked at that hospital, so she wouldn’t come see me. And I was pretty gravely ill. I wrote that out in the hospital. I think it was on a napkin that had come with my lunch, and it laid in the back of a notebook for years. And I finally arranged it as a song.

“My Black Name” has got a great nasty, dirty guitar tone. Do you remember what you were playing through?

We had one guest guitarist on the record—a guy named Matt Bohannon—and he loaned me a vintage Fender Bandmaster that he had. And we had a pedal in the studio that apparently is a prototype [Bixonic] Expandora pedal. It was built when the guy was getting the Expandora together. And we used that fuzz pedal, that amp, and for most of the record I used a Peavey JF-1 335 copy. “Let It Slide Reprise (No Doctor)” has my National Tricone Baritone on it.

Was it a tweed Bandmaster?

No, it was a blackface into a 2x12 cabinet.

Do you play exclusively fingerstyle? Do you ever use a flatpick?

Never use a flatpick. I wear acrylic nails on my right hand.

“Headlights” reminds me of the Rolling Stones a bit.

I’m playing in the same tuning that Keith wrote a bunch of his stuff in: open G.

Do you use many different tunings?

I use a whole bunch of different tunings. Most of them revolve around taking one of the two canonical slide tunings, open D or G, and then I’ll change a couple of strings on it to get a different voicing. For example, “Stagger Lee” is probably the most far-out tuning on the record. Bass to treble, it is C–A–D–D–A–D. The two center strings are the same D. “Stranger” is in standard tuning.

Mark “Porkchop” Holder’s Gear

Guitars2005 National Tricone Baritone

Peavey JF-1 hollowbody

Fender Squier Bass VI

Amps

Late-1970s Peavey Deuce combo

Fender Bandmaster (studio)

Effects

Sabine NEX-5400 Compressor

DigiTech DigiDelay

Bixonic Expandora (studio)

Strings and Picks

Ernie Ball Not Even Slinky (.012–.056)

Ernie Ball Slinky 6-String Baritone (.013–.072)

So sometimes you use just a standard open D and G, too?

Absolutely, I do. A lot of the time.

And on the National Baritone?

Because it’s got a longer scale, I will drop it down, normally three half-steps. I’ll be in open B relative to a standard open D tuning, and open E relative to G. That’s the whole point of having the Bass VI along—in case I want to preserve the key that one of those baritone tunes is in, I’ve got a longer scale guitar for that.

“Stagger Lee" is an interesting number. It’s one of the most recorded songs in American music, but typically, people write their own version of the tale, so they’re not really the same songs. Are your “Stagger Lee” lyrics your own?

I’ve heard that form used for that lyric. Mostly what I did on that version as far as the lyric was to listen to a whole bunch of versions. I would say maybe my lyric concept comes from somebody like John Hurt. I don’t know for sure.

It has echoes of Led Zeppelin, to my ear—kind of a “When the Levee Breaks” kind of nastiness.

The harmonica took it there for sure.

Speaking of which, how did you get the harmonica tone on “38?” That is a sick harmonica sound.

We decided to plug in a little crystal mic I’ve got that’s got a quarter-inch input, and see if we could play through the guitar rig, with the pedal on, without it completely exploding in feedback. We isolated me away from the guitar rig and plugged that thing in and the tone was really monstrous, and I started fooling around with it. “38” was pretty much improvised on the spot. I had a basic lyric idea for a song, but it pretty much just happened in the moment.

Holder’s previous album, the independently released Fry Pharmacy, was a one-man affair, recorded live as he sang and played his National resonator guitar and harmonica. Photo by Bill Johnson

On “Stagger Lee,” you get a little Middle Eastern, which I like. And there’s a weird church-bell sound at the end.

It is actually church bells from YouTube. I thought, “What would it be like if we put bells on it?” And we happened to find something that lined up pretty well on YouTube, and someone held their cellphone up to the vocal mic to get it on the track.

It worked! It adds an eerie tone to the proceedings.

Well, ask not for whom the bell tolls, right?

Touché! “Stranger” is another really cool tune. It’s kind of demented. The vibe reminded me of Nick Cave. Are you a fan?

Oh absolutely. I’m a big fan of Nick Cave. And also, that darkness end of Johnny Cash. The arrangement of it is completely an homage to Johnny Cash. It’s a funny thing. The only instrument I’m playing on that is a tuned-down lap-steel guitar that’s doing that warble. The electric lead you hear is Matt Bohannon, the guy who loaned us the Bandmaster. He gets real heavy on that song.

are the same D.”

Who were your idols as you were learning to play?

I would be remiss if I didn’t tell you I definitely had stuff that I went and sought out—all the blues guys: Muddy Waters and Robert Johnson and all that stuff. But the place and time I come from, and the culture I come from, involves pretty much walking around in a crowd of Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Allman Brothers. It’s the national music of the part of the South that I’m from. Whatever else I was listening to, that’s what was playing at me the rest of the time. You don’t have to go real far to hear that on that record.

As far as the original blues players, do you have any favorites?

One of these days I’m going to play something exactly like Fred McDowell and nobody will get to hear it, but it will make me happy. One of these days I’m going to play something that’s actually as loose and rhythmic as John Lee Hooker, and again no one will hear, but it will tickle me to death. I’m a huge Ry Cooder fan, too. I know that’s a different generation. His phrasing is really delightful.

You’ve been open about your struggles with depression and addiction. Is that something you feel was holding you back for a while?

Absolutely. It’s a funny thing. In my particular case, it all goes back to the fact that I’m mentally ill and I have medicine I have to take to control that. And when I don’t take it, I live in the woods in Northern California and I’m too paranoid to talk to anybody. I was completely off the grid in a recreational vehicle with no electricity or running water for about a year. And when I do take it, I get a record deal and go out on tour. Pretty easy to figure that out.

I’ve been walking around with a hat on that Patrick from Alive Records gave me that says “Alive” on it. You’d be amazed by how many people are like, “We wondered.”

YouTube It

Mark “Porkchop” Holder and his band perform “Disappearing” off his new album Let It Slide at the Wildwood Hotel in Willamina, Oregon. It’s a great opportunity to see Holder’s hybrid technique, employing both slide and traditional fretting, here in an open G tuning. And by using his ring finger for the slide, it frees him up to use his pinky to add a fourth to some of his slide chords to create a suspended chord. (You can see him employing this approach between 25 and 32 seconds.) On the outro solo, notice how he uses the open G string as a drone while fretting different notes on the B string. And check out how relaxed his right hand is as he accompanies his singing, alternately strumming and picking out notes with his acrylic nails.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)

![Rig Rundown: AFI [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62064741&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)