For the last 25 years, the Chicago band Tortoise has made primarily instrumental music that, despite often being labeled as post-rock, in actuality defies facile categorization. Tortoise’s commitment to experimentation is evident in its seven-album body of work, in which you’re just as likely to hear a symphonic percussion instrument as an electric guitar or an electronic blast of sound. Rock, 20th century classical, and jazz, among many other influences, are given equal consideration in Tortoise’s musical works.

In subverting the conventional structures and vocabulary of rock, Tortoise has given permission to bands like Godspeed You! Black Emperor, Mogwai, and Sigur Rós to do the same. To put it another way, Tortoise’s influence has encouraged more than a few bands to find their own experimental directions—not just indie-rock groups, but more mainstream acts, like Deftones, as well.

Tortoise formed in 1990 when bassist Doug McCombs (formerly of Eleventh Dream Day) and percussionist and keyboardist John Herndon (formerly of Poster Children) joined forces as a production team and a rhythm section for hire. That plan never really materialized, but McCombs and Herndon teamed up with drummer John McEntire and bassist Bundy K. Brown (both formerly of Bastro), along with percussionist Dan Bitney, to form the earliest incarnation of Tortoise.

The quintet’s self-titled debut (1993) featured the unconventional configuration of two bass guitarists and three percussionists playing not just standard drum kits, but marimbas and vibraphones. By Tortoise’s third album, TNT (1998), the group had enlisted Jeff Parker, a jazz guitarist known for his association with the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians). Naturally, improvisation and extended harmony then became more noticeable aspects of their music.

In 2010, the City of Chicago commissioned Tortoise to write a suite of compositions in celebration of the robust local community of jazz and improvisational musicians. The barebones themes Tortoise contributed to the project eventually morphed into the densely orchestrated compositions on The Catastrophist (Thrill Jockey), Tortoise’s first new release in seven years.

On the album, Tortoise expands on its original concept while visiting unexpected territory, like a cover of “Rock On,” by the English singer-songwriter David Essex, and the original song “Yonder Blue,” kind of an R&B ballad with Yo La Tengo’s Georgia Hubley. We chatted with Jeff Parker and Doug McCombs about the concepts at play on The Catastrophist, their idiosyncratic styles—and, of course, the tools of their trade.

Jeff, in addition to playing in Tortoise, you’re a prominent voice in modern jazz. Do you consider yourself a jazz guitarist or a rock guitarist? Jeff Parker: I consider myself a jazz guitarist, for sure. Jazz is where I learned the sounds that I hear, and this informs my approach to music in any situation. I still make a lot of my professional life as a sideman and leader in jazz music. I went to Berklee in the late ’80s with a lot of great jazz musicians. I was classmates with Roy Hargrove, Antonio Hart, Seamus Blake, Mark Turner, Joshua Redman, and Chris Speed, and I still play with a lot of these musicians. Before I joined Tortoise, I made my living playing in jazz organ groups in Chicago—some with Larry Goldings and Chris Foreman—doing a lot of pickup gigs.

How did you become involved with Tortoise? Parker: When I first heard Tortoise, I immediately became a fan. They were essentially just bass and drums: two drum sets and two bass guitars. This appealed to me because I’ve always had a bottom-heavy approach to playing the guitar. When I first started playing music I actually wanted to be a bass player. I picked up my sister’s guitar and played bass lines from Parliament-Funkadelic.

Anyway, the guys in Tortoise and I became friends and they started asking me to sit in. They already had a strong aesthetic thing with the bass and drums, and I didn’t really want to disrupt that. I think the reason they liked playing with me was because I had this guitar style that really fit well with the band. Those guys came up playing in punk bands before they started Tortoise to do something different. At first I blended in, but it’s become less like that over the years. Now the guitar’s more out front—but it’s not as if I’m playing like Jeff Beck.

How does your style fit into the band? Parker: It’s more conceptual than anything. There are definitely certain clichés associated with the guitar, and I avoid them. My approach isn’t about playing loud or screaming leads, especially within the context of so-called rock music. It’s often very sonic or ambient, or just using the guitar to play single-note melodic or repetitive things along with the rhythm section.

How do you reconcile the music of Tortoise with your jazz background? Parker:One of my favorite guitarists has always been Jim Hall. Even though he had a very specific sound and the context of what he was doing wasn’t very broad—usually within a pretty traditional jazz ensemble—he always sounded very open and colorful because of his approach to the instrument. The goal for me is to have a similar approach to playing jazz as I do when I play with Tortoise. But with Tortoise, the sonic landscape is broader than it is in a lot of the jazz I play. It’s music that demands I play with more color, using more effects and experimenting with different timbres, with EQs and percussive elements—there’s kind of an African guitar vibe in a lot of the music I play with Tortoise.

Guitarist Jeff Parker and founding member and bassist Doug McCombs are comfortable trading instruments and roles to pursue the low-end of Tortoise’s ensemble compositions. Photo by Tim Bugbee

Talk a little about the jazz you play. Parker: I play a lot of different stuff, from straight-ahead and standards to free improv, where it’s completely about playing the instrument in an unconventional way. [English free improvisation guitar pioneer] Derek Bailey is another one of my big inspirations; my musical world’s pretty wide open.

How has Bailey’s work informed your style—particularly in the context of Tortoise? Parker:The way he dealt with harmonics—not like the Tal Farlow–style harp harmonics, but finding extended, chiming notes all about the neck. That requires you play with a tight sound. The action of the instrument has to be pretty high, ideally with heavy strings. It requires a lot of resistance, and a setup like this adds presence to percussive sounds. Also, he was a big influence on me in terms of extended techniques: scraping the strings, using feedback intentionally. He was a real pioneer in finding a different way to deal with the instrument, pretty much as revolutionary as Jimi Hendrix, in my opinion. If you study improvised music on the guitar, there’s no way around it. He’s like Charlie Parker in that regard.

Doug, you play both bass and guitar in Tortoise, and guitar exclusively in your side project Brokeback. Do you think of yourself as more of a bassist or guitarist? Doug McCombs: I pretty much think of myself equally as a bassist and guitarist. It didn’t used to be that way. I played only bass for the first 20 years that I was in bands, and then, once I picked up a Fender Bass VI, it was sort of a gateway into guitar playing. I’ve been working really hard on the guitar for the last 10 years, and I’m pretty much sitting around and playing guitar if I’m at home. But after a long period of playing guitar, it’s really a relief to go back to the bass. I love its simplicity—I love locking in with an ensemble.

Jeff Parker’s Gear

Guitars

1950 Gibson ES-150

1983 Gibson ES-335

Amps

Music Man 75 combo

ZT Lunchbox

Effects

Boss FRV-1 ’63 Fender Reverb

Boss RV-3 Digital Reverb/Delay

Crowther Hotcake Distortion

DOD FX-17 Wah/Volume

Electro-Harmonix Freeze Sound Retainer

Electro-Harmonix Small Stone Phase Shifter

Maxon GE601 Graphic Equalizer

Moog MF-102 Ring Modulator

ZVEX Fuzz Factory

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EJ22 (.013–.056 with wound G)

Fender Extra Heavy picks

Doug McCombs’ Gear

Basses

1968 Fender Telecaster Bass

1963 Fender Bass VI

Early 1960s Kay K5915

Guitars

1963 Fender Jazzmaster with Mastery bridge

Baritone parts guitar with Lollar T Series pickups

Amps

Ampeg Portaflex B-18

Ashdown ABM-1000 head

Ashdown 610 cab with Blue Line speakers

Fender ’65 Twin Reverb reissue

Fender ’63 Vibroverb reissue

Gallien-Krueger 800RB head

Victoria Victorilux

Effects

Ernie Ball 250K Volume Pedal

Fulltone Full-Drive2 Mosfet

Last Temptation of Boost

Moog Moogerfooger MF-104M and MF-104Z analog delays

Vintage Pro Co RAT

ZVEX Woolly Mammoth

Strings and Picks

D’Addario EJ21 (.012–.052, with wound G for Jazzmaster)

D’Addario EXL157 (.014–.068, for baritone)

Fender 250B6 (.024–.084, for Bass VI)

Ken Smith Rock Masters (.045–.105, for Telecaster Bass)

Dunlop Standard Tortex picks (.60 mm)

How’d you get into playing the Bass VI? McCombs: The first time I saw one was in a guitar store around ’87. I was amazed when I picked up this instrument that I’d never seen before, and when I plugged it in I heard a lot of weird potential in it. At the time I was getting into a lot of different twang-y sounds: surf music, Ennio Morricone soundtracks, and other guitar-centric music. I’d already been exploring a more melodic side of the bass, and then I discovered this instrument that would allow me to get even more into that. I couldn’t afford to buy one for a long time, and I spent the whole time thinking about what I could do if I ever got ahold of one.

What’s it like to work with Jeff? How has he influenced your playing? McCombs: It’s great. I’ve learned a lot from him—a depth of knowledge about harmonic stuff. He’s really like a closet bass player. He has such a dark sound on guitar anyway, so it’s cool that he can play the bass sometimes and I can play guitar. It’s great to be in a band where everyone can be open enough to let each other play the instruments they’re good at.

The Catastrophist is the band’s first new album in seven years. What took so long? Parker: Our band is called Tortoise, so things tend to happen very slowly…

McCombs: A variety of things. One is that we’ve been together for so long that we try to be conscious about not falling into easy traps and to try to push ourselves away from different things we’ve done before. We always tell each other that it won’t take as long until we make the next record, but it gets longer and longer between records. And it’s just the nature of our band—we’re all sort of compulsively meticulous about little details, and it takes time to work that out.

Talk about the album’s roots. Parker: We got commissioned to write a new piece of music that demonstrated Tortoise’s ties to Chicago’s vibrant jazz and improvised music scene. There are five people in Tortoise and each one of us picked one person in the community we wanted to collaborate with and feature, and we composed a handful of pieces so that each performer could be featured on one. We made a suite of music out of the whole thing, and that’s pretty much how it came about.

Who did you pick? Parker: I picked a tenor sax player named Edward Wilkerson Jr.

McCombs:The person I knew would really add some great stuff to what we were doing is the piano player Jim Baker, who’s also a sort of wizard with the ARP 2600 [analog synthesizer]. He was one of the original five guest musicians we performed the music with in Chicago. Later, we did it in Minneapolis with local guest musicians, and in Paris, we brought some of the American musicians and also invited some French guests. When we decided to sit down and work on a new record, we used these materials to jumpstart it. Sometimes it takes a while for our wheels to get going when working on new material, and it was handy to already have these partially composed ideas.

So what was the music heard on The Catastrophist originally like and how did it evolve? McCombs: The main thing is since we were doing this project with improvisers, we had five pieces of music that were essentially little more than skeletal jazz compositions, like heads or melodies with room for the improvisers to solo over. When we were retooling these pieces for our purposes, we wanted them to be more like Tortoise songs and developed new parts, like bridges and such, to add structure and to make things more interesting. Tortoise isn’t really the kind of band that plays a melody and then someone solos for 20 minutes. That’s fine—and, in fact, fun for a special project—but not at all what we’d go for on an album.

With music that’s so texturally involved, you must have a nonconventional compositional and recording process. How does it work? Parker: One person introduces an idea or ideas to the group that everybody expands on. It could be anything from a sampled drum pattern or just a riff or a chord progression, and everybody adds their thing to it. Sometimes someone will come in with a complete intricate composition and we learn it. When you introduce something to the band you have to be open to the idea that it’s going to change as people add to it. We’ve come to realize that when everyone contributes, it’s the most interesting.

McCombs: Most of the time a song starts as just a little idea, a chunk of melody or some sort of unusual chord sequence, and sometimes just a rhythm. We’re such a rhythm-oriented band and sometimes someone has an idea for an interesting pattern we haven’t tried before. So, 80 percent of the time we’re working on something that isn’t structured at all, throwing ideas around and trying to pull them into some kind of form. We do it not by playing together in a room, but by recording bits and pieces and seeing what happens through editing. Sometimes we might go back and learn [the resulting music] with the band and sometimes not, whatever works.

Before beginning a tour, “we send emails back and forth about what parts each person should focus on and then spend a week or so in a rehearsal room, ironing everything out,” explains Doug McCombs. “It’s the exact opposite of how most rock bands work.” Photo by Tim Bugbee

So recording technology plays a big role in your compositional process. Parker: Yes. I recently did a podcast and was asked how technology has affected the way our music has progressed. It totally has. This current version of Tortoise exists because of the medium of hard-disk recording. Our process very much relies on how easily you can edit and move audio around, to add or remove things. It’s a big part of our compositional process, and it can be compared to making a patchwork quilt.

Talk a little more about the squares in your quilts, if you will, on a technical level. Parker: In the recording process, a lot of songs change meter. Something that started in 3/4 might end up in 5. Somebody might’ve brought a demo of something completely different, and we’ll kind of throw it on a part of another tune and let it become something else. Again, it’s all about taking small ideas and expanding on them, and that’s pretty much what we did with all the source material from the original Chicago suite. Also, this recording process is especially useful these days, since two of us are now in California.

You both play guitar and bass. How do you decide who’ll play which instrument on a given piece? McCombs: It depends on which tune most needs that person’s feel. If the song calls for my particular style, then I’ll play it. If not, I might play guitar and have Jeff play the bass. It all depends on which personal aspects we want to be more prominent on a given song. In general, as far as guitar goes, Jeff and I have pretty different goals for tone and the role that instrument plays in the music. There’s plenty of times were I’ve played all the bass and guitar on the recording and then Jeff has to do one or the other live and vice versa. It’s kind of just mix and match—whatever would be the best and most practical thing for the band.

YouTube It

Although Tortoise’s concerts are ensemble performances that showcase the band’s arrangements, this live duet between guitarist Jeff Parker and drummer John Herndon brings Parker’s improvisational approach into sharp focus. His string scraping and ringing harmonics reveal the depth of Derek Bailey’s influence on his playing—especially when he starts literally digging into his guitar’s strings at the 9-minute mark.

Tortoise tends to avoid vocals, but The Catastrophist has two tracks with singing. How did this come about? McCombs: The first one happened because John McEntire and I were simultaneously fascinated by that song, “Rock On,” by David Essex and we thought it’d be awesome if Tortoise were to do a version and see what happens. We weren’t thinking about putting in on The Catastrophist—maybe a special online release or EP—and in the end the consensus was that everyone wanted it to go on the album. A friend of ours, Todd [Rittmann, of noise-rock band U.S. Maple], did a great job with the vocals.

The other song, “Yonder Blue,” started out like a normal Tortoise song and when we were putting it together it just seemed like a dusty old soul jam to us— something that really should have some singing on it. We’ve been friends with Georgia from Yo La Tengo for, like, 30 years, and we called her and said, “Hey Georgia, can you sing on this?” We didn’t give her lyrics or any sort of restrictions, so what you hear on the record is what she came up with. We all really loved it, and though people have been trying to get us to put singers on our records for years, we didn’t set out to do that. It’s just a coincidence that the record has two songs with vocals.

How do you prepare to tour in support of an album like The Catastrophist, recorded in so many bits and pieces? Parker: We have to do some homework because of all the layering involved in our process. We have to kind of whittle down the tunes to their bare essence. Some of the stuff is tricky—logistically and otherwise. With John’s crazy synth collection, he can’t take that stuff on tour. So we spend a bit of time at home making samples so we can load them onto our software for triggering live.

I do play mostly guitar in the band, so I’ll pretty much just figure out my own parts, but I also learn some of Doug’s parts—he’s a great bass player and a great guitar player. This can be tricky, because you’ve got to consider the various pedals we use and the fact that the guitar and bass sounds get transformed in the mix through various reverbs, delays, and tremolos.

McCombs:The first step is to decide who will play what instrument on what song. We’ve got three drummers who also play keys and mallets and various other sundries. Jeff and I, of course, split our time between bass and guitar, and Dan also plays a lot of bass and a little guitar. We send emails back and forth about what parts each person should focus on and then spend a week or so in a rehearsal room, ironing everything out. It’s the exact opposite of how most rock bands work.Ambient Funk

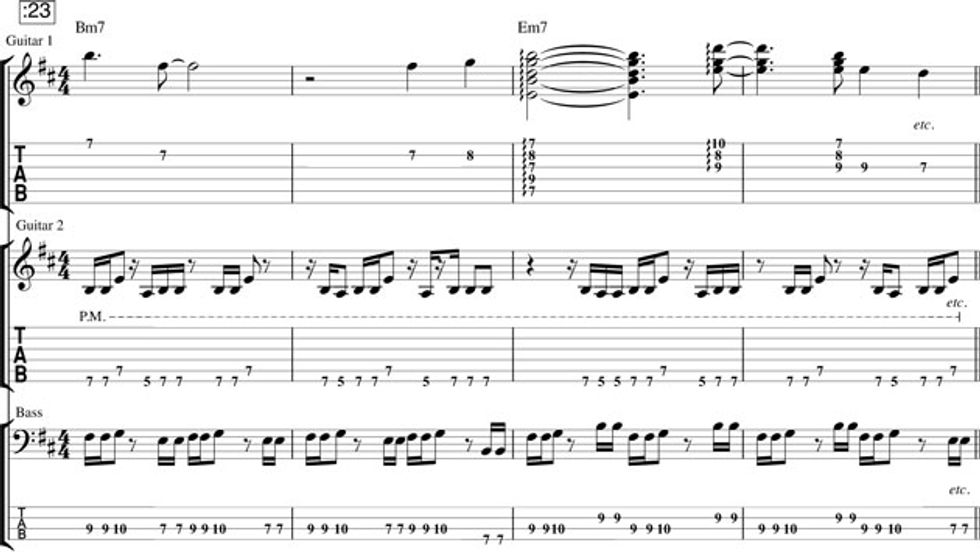

This adaptation from the song, "Tesseract" shows the influences of dub, minimalism, and funk in Tortoise's music. Notice how the palm-muted lower guitar part, which wouldn't be out of place in a James Brown song, interlocks rhythmically with the bass line. Meanwhile, the melody, played on the higher guitar in contrastingly long rhythms, floats above this bed.

![Rig Rundown: Russian Circles’ Mike Sullivan [2025]](https://www.premierguitar.com/media-library/youtube.jpg?id=62303631&width=1245&height=700&quality=70&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)